Last updated: June 12, 2025

Article

Connections Across the High Plains

NPS photo

Our Place in History

Welcome to the National Park Service's High Plains Group where histories span over 200 miles across the group’s four connected sites. Resting among the prairies and grasslands of southeastern Colorado and northeastern New Mexico, these locations witness a story as vast as the scenic expanses they cover. Collectively, they cut across more than just territory. They sweep through cultures and eras, politics and rivers, species and kinship, trade and conscience.

Ancient Ground

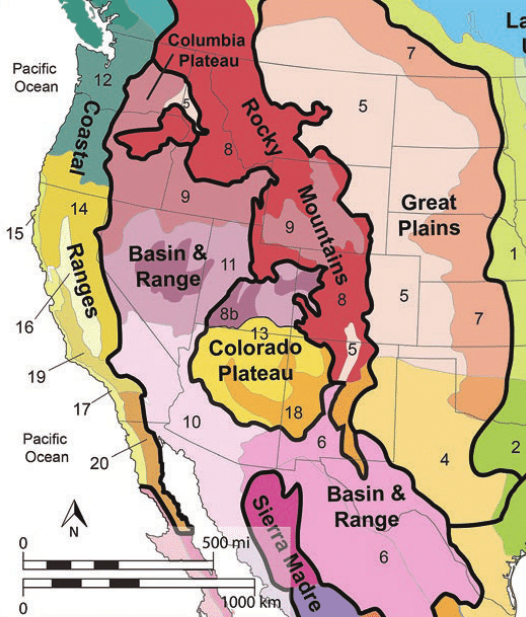

The junctions among our sites begin with the ancient ground which supports them. In a dramatic prehistoric tectonic plate subduction, the mountains of the Great Continental Divide emerged to create an imposing vertical barrier across the American continents. From the Arctic to South America, layers of earth shuffled into new locations and configurations. Minerals and ores deposited themselves in obvious surfaces and secluded crevices. Major rivers like the Arkansas and Cimarron advanced their courses southeastward to seek their lowest point. Land softened, crust settled, and soil prepared itself for hardy vegetation.

Theoretical Development of Ecological Green Roofs. Dvorak, Bruce and Bousselot, Jennifer, 2021. Graphic by Dvorak, Bruce and Maciejewski, Trevor.

Prehistoric Finds near Capulin Volcano

Capulin Volcano National Monument near Folsom, NM reminds us of a similarly volatile geologic and migrational past. Although the volcano erupted approximately 62,000 years ago, it is part of the Raton-Clayton Volcanic Field which contains a series of extinct volcanoes, some fifty times its age. Its cinders, nearby fossils and surrounding landscape anchor our understanding of the area’s ecological and cultural beginnings. To appreciate the location's time stamp, cowboy George McJunkin stepped into an archeological spectacle back in 1908. There, only five miles from the national monument's idyllic cinder cone, flood waters receded to reveal the ribs of bison antiquus alongside a stone folsom point. This ancient triangular tool coupled with animal remains served to chronicle the earliest co-existence between Native American people and the ancestor species upon which Plains dwellers would perpetually build their lives - the American buffalo.

NPS (Adobe Stock)

Fort William’s Material Success

William and Charles Bent of the Bent, St. Vrain, and Company partnered with the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho to procure and process tens of thousands of furs from the tens of millions of buffalo that grazed the Plains each year. In just a few seasons, Bent’s Fort, also known as Fort William, rose to commercial supremacy. With reliance on and trade among its Plains Indian kin and neighbors, this rural hub evolved to scrape, mold, polish and issue a currency which had once been animated. In the Borderlands, pocket-sized silver coins gave way to heavy and malleable brown tender – the buffalo robe.

NPS photo

Trade and Treaties

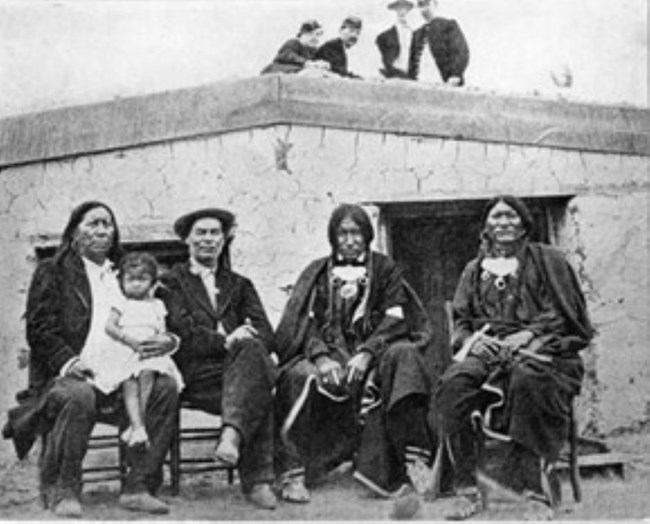

When strong international economies like these grow and flourish, so does competition. In turn, the desire for sovereign nations to safeguard and expand their resources and protect their population surges. The scale of competition plays out within the hundreds of square miles surrounding our four National Park Service sites at various eras of American history. Trade agreements and treaty making during the 19th century became essential transactions whereby Nuevomexicanos, Native American Plains Nations, Anglo settlers, and the U.S. government attempted to secure their place amid the buffalo-filled prairies and the life-sustaining waterways which would sustain them.

NPS

In the Borderlands, the Treaty of Fort Laramie or Horse Creek Treaty in 1851 offered compensation to Plains nations for increased Anglo incursions into their hunting ranges, but active measures to protect Native homelands were short-lived. The Treaty of Fort Wise was represented by only a small contingent of Cheyenne in 1861 and caused Cheyenne and Arapaho homelands to be reduced to one-thirteenth of its original area. Signed at Bent’s New Fort by the William Bents’ son, Robert, Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle, and other acquaintances, the Fort Wise Treaty underscored the centrality of trade in the hopeful continuation of trusted partnerships on whom livelihoods depended.

NPS

November 29, 1864: The Sand Creek Massacre

Trust by way of spoken promise ran profoundly shallow on the Sand Creek near present-day Eads, CO in November of 1864. The tidal wave of gold-seeking emigrants and the military maneuvers of the Civil War necessitated additional measures of safety for Plains nations. Having already been used as a regular encampment by the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho and within close proximity to the military presence at Fort Lyon, Governor John Evans and Colonel Chivington issued assurances that the tribes who joined Black Kettle at Sand Creek would be granted peace and the protection of the U.S. Army. Yet, within the same month, in an unprovoked attack at dawn, Chivington and his 3rd Colorado cavalry ignored Black Kettle’s white flag of surrender alongside the emblazoned banner of stars and stripes. Dozens fled their tipis and clawed at the frozen earth to prevent being numbered among the two hundred plus Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children, and elderly who were massacred that morning.

Amache Preservation Society, McClelland Collection.

Swept by Political Tides

Just as the southern Cheyenne and Arapaho at Sand Creek felt the effects of national expansion, so too, eighty-one years later, another group of Americans would be by caught in politcal turmoil. Less than fifty miles south of Sand Creek and almost thirty miles west of Bent’s New Fort, thousands of Japanese Americans were escorted by executive order from their California homes and livelihoods to the Granada Relocation Center in August of 1942. Having endured the closure of their businesses along the coast, these citizens also turned their attention groundward. From the especially dry High Plains turf they hoped to wrest both nourishment and longevity.

In the 1830s, Josiah Gregg observed, “This tract of country may truly be styled the grand prairie ocean.” Characterized by an arid climate, frequent drought, high winds, severe temperatures, and occasional flooding, the people of the High Plains region have had to boldly adapt to “ocean” surges and its impact on provisions. Where sandgrass, wild asparagus, buffalo gourd, and prickly pear cactus flourished as traditional staples, food sources gained through trade with New Mexico, such as corn, squash and beans were valuable additions to a limited diet on the southern Plains during the fur trade era.

NPS (Adobe Stock)

Reaching for Home

The earth’s natural receptivity to cultivation in this prairie climate has changed little over time. Only through painstaking irrigation does robust vegetation yield in this terrain. Yet, like the earlier Native American communities and settlers preceding them, Japanese American incarcerees also sought foods from abroad. Resisting the restrictions that confinement under guard generally poses, Amache’s incarcerees worked to expand their diet with their bare hands. By turning the clay and sandy soil over with hoe and shovel, they not only refreshed their diet through gardening, but actively resisted the withering of their culture. This resistance would resurface in another way when incarcees opted to call their camp Amache instead of Granada. Amache (Cheyenne, Walking Woman) and her husband, John Prowers, had been successful business owners in the county in the mid 1800s; the latter having worked at Bent’s Fort for several years. Amache’s father, Cheyenne Chief Ochinee, had been murdered at Sand Creek and Amache took an active role in advocating for the needs of her people.

Despite resistance and cultural nurturing, the waters of the Pacific beckoned from over a thousand miles away. Separated from the salty shores and jagged fault lines of California, two Japanese Americans in Granada, Colorado began operating Granada’s Fish Market during the incarceration period. On their meat counter rested abalone, a seafood harvested in great numbers along the California coast. The presence of this traditional seafood on the family dinner table signaled celebration. With abalone, holidays like New Year’s empowered cultural identity and all the more so during an era when having Japanese ancestry was washed in mistrust.

NPS

Routes Connecting Products and People

Perhaps unexpectedly, the iridescent abalone adds a broad connective tissue to the human histories of the park service's High Plains Group sites over time. Its presence in the geological record predates the Continental Divide, Capulin Volcano's eruption, and bison appearance on the continent. However, long before Mexican independence and merchant traffic pounded the Santa Fe Trail, ancient abalone caches accrued in nearby southern Plains village sites. Centuries before the fur trade, the vitality of Native American intertribal commerce centered on shell trading. And with the distribution of shells came a trail stretching from the west coast across the Mohave Desert and east to the Pueblo people. Pueblo traders then strung dozens of these colorful calcium carbonate shells together as they migrated north to the Plains in a pattern not unlike Mexican teamsters or Bent’s Fort traders on the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro or Santa Fe Trail in the nineteenth century.

Just as buffalo robes had been used as currency during the fur trade era, so too was the abalone shell a currency for Native American tribal nations on the west coast centuries earlier. The mollusk’s worth seemed to have endured several passing trends of new American commodities. A snapshot during the 1840s shows that one abalone shell far exceeded the value of one buffalo robe. Nineteenth century writer, Rufus Sage, comments, “A small trade in the shells of the pearl oyster is carried on with the Arapahos, Chyennes, and Sioux, by the Spainards, which yields a very large profit, - a single shell frequently bringing six to eight robes.”

Amache Preservation Society, McClelland Collection.

Cultural Exchange

Value, we are taught, is largely determined by the principles of supply and demand. However, history demonstrates economic principles are applicable to more than just material goods themselves, but also to the human exchange of cultural currencies underlying them. Trade has more often than not occurred in places where a lack of access meets an increase in opportunity.

At the beginning of World War 2, the abalone industry had been fortified by Japanese American labor in California. The political tide of forced relocation caused an immediate labor shortage along the West coast. Nevertheless, Japanese American fishermen had previously transferred their harvesting knowledge to a few Mexican fisherman whose labor force expanded to keep the industry afloat throughout the war. Canned abalone tins clanged their way into the rucksacks of deployed soldiers as a wartime food, essentially becoming one of the fuels by which Americans would advance toward world peace. For Japanese-American incarcerees, had their fishermen not passed on their harvesting skill to Mexican replacements, those at Amache's camps would have been denied a meaningful dietary cultural practice in a disheartening time.

NPS

Uplifting Intersections

In real ways, as seen at Bent’s Fort and Amache, the transfer of cultural knowledges is bidirectional. It drives the cycle of commercial industry, exerts influence on political outcomes, and perhaps most importantly uplifts the human experience with cultural integrity. Today, as through history, cultural knowledges emanate first from the land, its fissures, depressions, banks and shorelines. To absorb a National Park Service historical site is to grasp where human endeavor meets the irresistible outflow of earth's potential.

Whether by the overturning of grasslands or the circulation of water, the crossroads of history, culture, and commerce are rooted in geologic time. Routes of human experience mimic environmental realities often by taking more circuitous paths than linear ones. While some past interactions have laid the earth and its inhabitants bare, other transactions have been conducive to human and environmental harmony. Yet, intersections, no matter where they exist, inherently possess the kinetic capacity toward mutual benefit. They can heighten rocks over prairies, carry species beyond habitats, translate peoples through borders, lift resilience past harsh conditions, and infuse difference with power. As you encounter the High Plains crossroads of Capulin Volcano, Bent’s Old Fort, Sand Creek Massacre and Amache monuments and historic sites, it is our hope that you feel as grounded as those ancient herds of buffalo within these landscapes. May these histories reveal how the High Plains Group of parks with their rich and often eruptive pasts suggest opportunities for a nationally transformative future.

Tags

- amache national historic site

- bent's old fort national historic site

- capulin volcano national monument

- sand creek massacre national historic site

- santa fe national historic trail

- bent's old fort

- sand creek massacre national historic site

- capulin volcano national monument

- amache national historic site

- bent's old fort national historic site

- trade

- japanese american incarceration

- buffalo robes

- abalone

- trade routes

- santa fe trail

- volcano

- bison

- treaty

- high plains group

- high plains desert

- folsom

- southern cheyenne

- cheyenne and arapaho tribes

- 1851 treaty of fort laramie

- treaty of guadalupe hidalgo

- black kettle

- granada

- cultural exchange

- barter

- fur trade

- 19-century westward expansion

- westward expansion

- world war 2

- colorado history