Last updated: May 19, 2025

Article

How Old Are Petroglyphs, Pictographs, and Inscriptions?

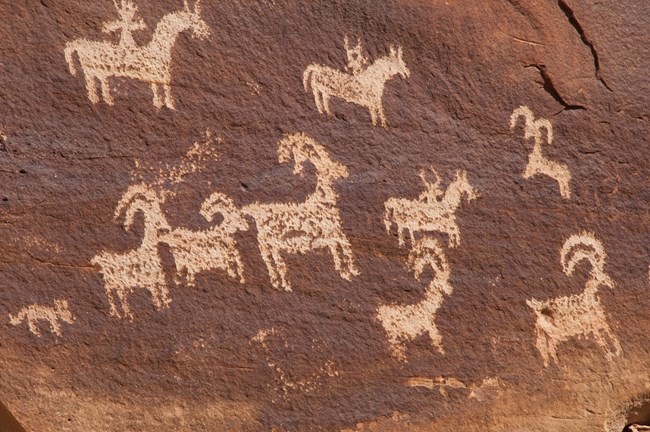

NPS photo.

“How old is it?” is a question commonly asked about petroglyphs, pictographs, and inscriptions. The answer depends on who you ask and how they know.

Age or Time

Native Americans may see time as circular or cyclical, with no beginning or end. Rock markings are part of their cultural traditions and ways of knowing that extend to time immemorial. Oral traditons pass knowledge from generation to generation about what rock markings mean and why they are significant.

Western peoples tend to view time as being linear. They seek chronological sequences and points in time. Anthropology, archeology, chemistry, geology, and history are some of the disciplines that study rock markings. They collect and analyze information to understand where a set of markings fit on a time line. To do so, they seek absolute dates and chronologies.

Native American and Western approaches to time are complementary. By working together, Native American and Western scientists can gain a deeper understanding of when rock markings were made and how old they are.

The oldest rock markings in America are thousands of years old. Rock markings in the Pyramid Lake Indian Reservation in Nevada date to between 14,800 and 10,500 years ago. Markings at the Paisley Caves in Oregon date to 14,300 BP or roughly 12,000 BCE on the basis of radiocarbon dates from DNA found nearby. The caves are on lands ceded by the Klamath Tribes. Petroglyphs at Tlingit Aaní (“kling-it") on Kaachxaan.akw’w (how to pronounce), part of Petroglyph State Park in Alaska, are between 8,000 and 10,000 years old. The Tlingit (“kling-it"), ancestors of the Alutiiq (“al-yoot-eek"), created them.

Style

Style is another way to date rock markings. Motifs and techniques can be compared from place to place, and over time. In some places, the style changed from abstract shapes to representational figures. Nonrepresentational designs are found in all places for all time periods. Archeologists infer age by finding parallels with motifs on artifacts from nearby sites. It is not clear why the styles changed or the degree to which the changes were linear over time.

NPS photos.

Content

The content of rock markings can provide an approximate or precise date.

"Approximate dates" draw on the principle that rock markings cannot show something not yet introduced.

Around 1300, the katsina (“katsi-na”) and the religion around it developed among Pueblo cultures in the Southwest. Only then did pictographs begin to depict katsina dancers and masks, and cloud terraces and parrot motifs. Katsina are benevolent spirits who act as intermediaries between the gods and people.

NPS photo.

Circa 1540, Spanish explorers arrived in the Southwest. They introduced horses, a new language, written numbers, and Christian symbols. These motifs appear in petroglyphs only after their arrival.

Typical scenes like this one from Arches National Park depict horses and riders moving among herds of animals, or on route in groups.

NPS photo.

NPS photo.

Layering

New rock markings may be carved or painted over old ones. The oldest images are at the back – they are painted over or cut through by new markings. The newest images at the front have no lines or shapes cutting into them. It is often difficult to know the time depth between the oldest and newest markings. This creates a sequence from back to front.

“Desert varnish” is a darkening, or patination, of rock. Petroglyphs carved into desert varnish expose the lighter rock color below the surface. Over time, the rock surface will re-varnish in a process called “repatination.” Repatination occurs at various rates and degrees. A great degree of repatination indicates greater age than an image that shows only some. As a result, the degree of repatination provides a relative idea of how old an image may be.

NPS photo.

Lichens

NPS photo.

Lichens consist of fungi and algae that grow on rock. Fungi grow around the algae to buffer it from the weather. It takes a long time for them to cover a surface, but when they do, the coating is very durable. Many lichen grow less than a millimeter per year, but lichens can live for thousands of years.

Lichenometry is a technique to date rock markings using indices of lichen growth. It analyzes the age of the lichen’s thallus. It provides the best data for the most recent millennia and is most precise up to 500 years. A rock marking is younger than the lichen when the carving goes through it. It is older when the lichen grows over the carving.

Radio Carbon Dating

Radiocarbon dating is also called carbon dating, carbon-14 dating, or C14 dating. All plants and animals need carbon to survive. When a living thing dies, it stops exchanging carbon with the environment. The amount of C14 it contains undergoes radioactive decay. Over time, it contains less and less C14. The remaining C14 can be measured to determine when the plant or animal died. The older the sample, the less C14 there will be. C14 dating is most reliable for dates up to approximately 50,000 years ago.

One way to radiocarbon date pictographs is to analyze organic pigment. For example, charcoal (the pigment most often used for black painting) dates to the death of the plant from which it was made. It may not, however, date the pictograph itself. As a result, the charcoal or the wood used to make it could date much older than the pictograph. C14 thus provides a ballpark date for when a pictograph was made.

Comparative Evidence

Oral history, archeological data, and historical documents provide comparative evidence for dating rock markings. Working from multiple perspectives strengthens our understanding of rock markings.

Native American oral history draws on memories and information passed from generation to generation. It can help interpret the content and age of rock images and place them in a cultural context.

Archeologists extrapolate dates from evidence found at nearby sites and analysis of collections. Archeological data includes findings from site excavations and collections analysis. Charcoal, diagnostic artifacts (such as lithic tools or ceramic types), and tree rings are some ways archeologists place a site in chronological time.

The location of rock markings near buildings provides another clue. When archeologists know the date of a building, they may assume that the images were made while the building was in use.

NPS photo.

Historical documents kept by Europeans recorded their observations and travels. They correlate the creation of rock markings with Europeans’ travel and exploration through a place. Historical documents also help to place rock markings into context by tying them to larger currents and trends.