Last updated: November 8, 2022

Article

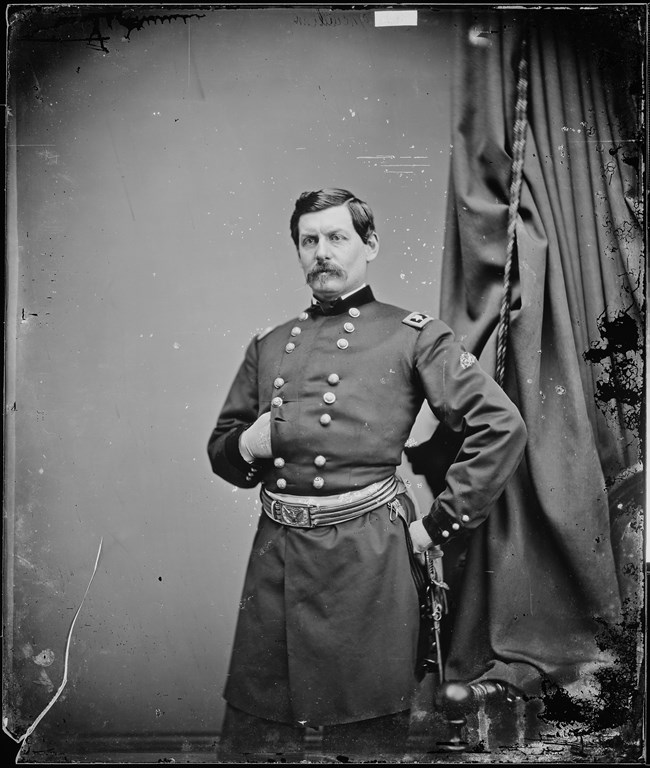

In the Aftermath of Antietam: How does Burnside get Command?

Library of Congress

Burnside, 38 years old, had provided the Union cause one of its few bright spots in the war, at least in the Eastern Theatre, when he orchestrated the successful North Carolina Campaign earlier that year. Capturing wide stretches of the North Carolina coast, especially around Roanoke and Cape Hatteras, Burnside gained valuable footholds for the United States.

After his service in North Carolina, Burnside transferred to the Army of the Potomac. During the Battle of Antietam he famously commanded a wing of the army, trying to get across a bridge that now bears his name.

Burnside counted among his close friends the current army commander, George B. McClellan. McClellan faced his own troubles after the Battle of Antietam. McClellan’s perceived slowness angered many in Washington, including President Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry Halleck.

Having issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln desired a victory before the new year, when the proclamation would go into effect. Lincoln did not think McClellan would deliver.

Lincoln had in fact already offered Burnside command of the Army of the Potomac twice before. Both times Burnside declined. In his own words, Burnside later explained why he had demurred, telling a congressional committee,

“I told them what my views were with reference to my ability to exercise such a command. . . that I was not competent to command such a large army as this.”

National Archives and Records Administration

Because of a driving snowstorm, it took two days for the orders to arrive at Burnside’s tent, north of Warrenton. Burnside’s hands were tied. If he did not accept command, the rumor was that Lincoln would give the army to Joseph Hooker, a personal rival of Burnside. With that in mind, Burnside accepted and wrote to Halleck,

“The General-in-Chief will readily comprehend the embarrassments which surround me in taking command of this army at this place and at this season of the year. Had I been asked to take it, I should have declined; but, being ordered, I cheerfully obey.”

One of Burnside’s new subordinates, Darius Couch, wrote later,

“Those of us who were well acquainted with Burnside knew that he was a brave, loyal man, but we did not think that he had the military ability to command the Army of the Potomac.”

New to command of an army he didn’t want, and swallowing his own reservations, Burnside now had a campaign to plan.