Last updated: April 4, 2024

Article

How a Navajo Scientist Is Helping to Restore Traditional Peach Horticulture

Reagan Wytsalucy’s desire to help her people took her on a journey to discover the fruit’s storied heritage—and reconnect with her own.

By Susan Dolan, with Reagan Wytsalucy and Keith Lyons

Image used by permission of Reagan Wytsalucy

Although drifts of pink peach blossoms no longer stretch for miles as they did in the mid-1800s, Navajo families still grow peach trees in Canyon de Chelly.

People have grown peach trees in the vast desert landscape of the southwestern United States for hundreds of years. Peach orchards in Canyon de Chelly National Monument were first sown by predecessors of the Hopi people and in the 1700s by the Navajos. They were part of a local economy of shepherding, small-scale farming, hunting, and gathering. Of the orchard fruits adopted by the Navajo people, the peach became the most culturally significant. It was a versatile food, trade good, and feature of traditional ceremonies. The peaches are now predominantly modern varieties, but young Navajo horticulturist Reagan Wytsalucy, who is collaborating with the National Park Service at Canyon de Chelly, understands there’s great interest in returning to the centuries-old, traditional peaches. Her groundbreaking research shows why.

Wytsalucy is working with Indigenous communities to increase the availability of traditional crops for original uses. She hopes this will counter food insecurity, increase resiliency, and perpetuate traditional cultural knowledge. She has devoted much of her career to finding the traditional peaches of the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni people. Along the way, she has made remarkable discoveries and developed a deeper bond with her own heritage. Through her academic and professional training in horticulture, she combines the science of genetic and physiological research with the insights of traditional knowledge. Her findings are significant for heritage preservation, cultural resource management, and biodiversity conservation.

A Fruit with a Fabled Past

The journey of the peach into the hands of Navajo and Puebloan people of the Southwest spanned continents and centuries. It led through times of great adversity. The story began in Zhejiang Province, China. That is where the peach originated and has been cultivated by Chinese people for thousands of years. The fruits were prized. About 2,000 years ago, silk traders and Greeks took them into Persia, and from there into Greece, Italy, and other temperate areas of Europe. Peaches made the transatlantic voyage to the New World in the 16th century with Portuguese and Spanish explorers. Conquistadors, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries, and Indigenous people took them north from Mexico.

For several hundred years, the peach, or “Diné didzétsoh” in Navajo, has been an important food source for the Navajo and many Puebloan tribes of the Southwest.

During the 1600s and 1700s, Spain spread its empire across the lands of the present-day United States. The Spanish empire included what is now Arizona and New Mexico, and parts of Utah and Colorado. The Spanish mission system aimed to expand the empire and subjugate Indigenous people. Catholic priests and friars from Spain ventured into remote areas of the Southwest to build missions. They worked with native people, planting crops, hunting game, and preaching Christianity. A 1630 report by Portuguese Franciscan Fray Alonso de Benavides to King Philip IV of Spain recorded an abundance of crops within pueblo communities of New Mexico. These included peaches, plums, apricots, corn, squash, and beans.

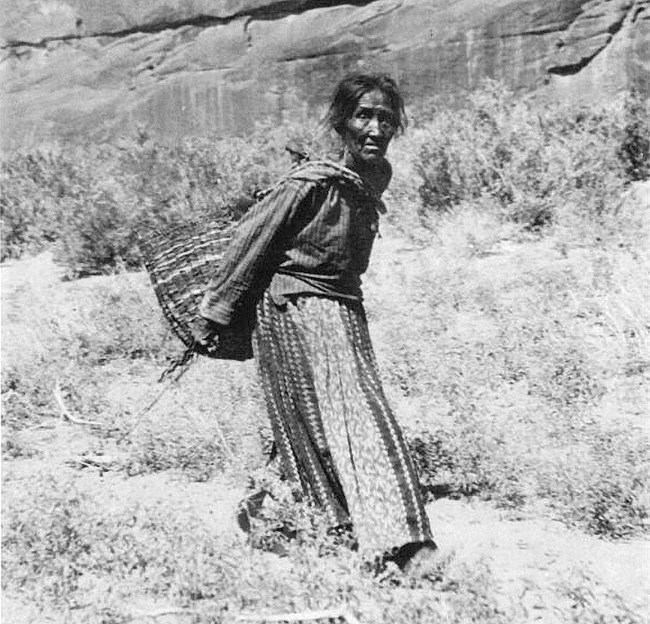

For several hundred years, the peach, or “Diné didzétsoh” in Navajo, has been an important food source for the Navajo and many Puebloan tribes of the Southwest. Canyon de Chelly became the center of Navajo peach production by the 18th century. Navajo people planted peaches on alluvial terraces watered by surface runoff from the cliffs. They grew the trees from seed rather than as grafted varieties or from rooted cuttings. Through inbreeding and crop selection, they created populations adapted to the local desert climate and alkaline, sandy soils. The trees bore distinctly small, apricot-sized peaches with white, freestone flesh. Great congregations of Navajo people came for the September harvest to Canyon de Chelly and its main tributary, Canyon del Muerto, to gather the peach crop. They carried the fruits in wickerwork burden baskets of sumac, willow, or oak twig.

Image reproduced by permission of the Los Angeles Conservatory

Nineteenth and 20th-century historians, archeologists, and ethnographers, and contemporary knowledge-keepers showed that Indigenous people used Canyon de Chelly peaches in different ways. They boiled unripe fruit, ate them when ripe, or sun dried and stored them for later consumption and trade. They stewed the dried fruit to soften it before eating. They traded fresh or dried peaches for meat, sheep, baskets, and animal skins. In Canyon de Chelly, they dried fruit on flat rocks, boulders, ledges, cave floors, or the roofs of storage structures.

Women split the peaches, removed the pits, and spread the fruit open side up to dry. They gathered dried fruits in skin sacks then stored them in pits or masonry storehouses under cliff overhangs for winter food. They reserved some peach pits for sowing new trees and as rubbing tools to polish cooking stones but discarded the majority. These sometimes became deep debris piles. They dug channels from springs by hand to irrigate orchards and fenced the orchards to protect them from wildlife. Most peach trees weren’t pruned, and the trees developed multiple trunks like large shrubs. Navajo cultivators only pruned peach trees to remove dead wood and did not thin the fruits on the tree.

A Persecuted People Saves the Seeds of Its History

Navajo peach culture spanned decades of Spanish colonization. The Spanish colonists suppressed the Navajo people’s cultural and spiritual traditions for generations. The Navajo people’s resistance to their subjugation reached a climax in 1680. More than 17,000 Indigenous people participated in what become known as the Pueblo Revolt. They were influential in driving the Spanish from the Southwest. But Spain re-established control gradually, and the mission system grew and prospered in the 18th century.

Navajo people adapted by becoming skilled livestock herders, capitalizing on the influx of Spanish domesticated animals, particularly sheep. Numerous wars of independence in the early 19th century led to new national boundaries in the colonial provinces of Spanish America. Spain ceded the lands of Alta California to Mexico in 1822. The United States won the region from Mexico in 1848. That year, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo established the boundary between the United States and Mexico. An 1853 treaty following the Gadsden purchase established the modern boundary in New Mexico and Arizona.

Many sought refuge in Canyon de Chelly, but the Army burned and cut down the peach orchards, destroyed crops, and killed livestock.

With the 1849 California Gold Rush, thousands of miners traveled through the Southwest. This led to a population boom and new settlements. The Navajo people defended their territory from the incoming settlers. But the United States Government attempted to protect the migration of non-native settlers and free up lands for settlement, using military campaigns to coerce treaties with Native American tribes. Across the United States in the 19th century, warfare killed thousands of Indigenous people, and the federal government forced them to relocate onto reservations.

In 1863, the U.S. Army forced the Navajo from their land to Bosque Redondo on the Pecos River in New Mexico, to be held under Army guard at Fort Sumner. Many sought refuge in Canyon de Chelly, but the Army burned and cut down the peach orchards, destroyed crops, and killed livestock. These violent incursions eventually forced the Navajo to surrender. Nine to 10 thousand people were force-marched hundreds of miles on the “Long Walk,” where many perished by starvation. By the end of 1864, 75 percent of the survivors were at Bosque Redondo. The rest fled westward or elsewhere, living in small groups or among friendly neighbors. Among their possessions were peach seeds carried from Canyon de Chelly.

In 1868, the Navajo successfully negotiated a treaty with the United States Government. This allowed them to return to their homeland within the four sacred mountains of Blanca Peak, Mount Taylor, San Francisco Peaks, and Hesperus Mountain. The treaty established an official Navajo reservation, incorporating the lands of Canyon de Chelly. Originally a smaller portion of their ancestral homeland, the reservation was eventually enlarged to its present size as the nation’s largest Native American reservation.

This ran contrary to most federal regulation of Native American affairs in the 19th century, particularly the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887. The act allowed the federal government to break up reservation land to assimilate Native Americans and make land available for private ownership. Under the act’s provisions, the United States took two thirds of the 138 million acres held by Native Americans prior to the act.

Image credit: NPS

Horticulture Returns but Tradition Wanes

Remarkably, the Navajo of Canyon de Chelly summoned the fortitude to re-establish their orchards, crops, and sheep herds, including those that avoided capture or returned from internment. They sowed peach seeds they had saved from destruction. They cultivated trees that could be resprouted from cut stumps. By the 1870s, U.S. military personnel and Indian agents had documented newly planted trees and old trees that had survived the 1864 devastation. Multiple accounts indicate the Navajo had re-established the peach orchards of Canyon de Chelly by the 1880s. Cosmos Mindeleff, an archeologist who investigated the canyons in the 1880s and in 1893, wrote this:

One of the characteristic features of the canyons at the present day is the immense number of peach trees within them. Whenever there is a favorable site…there is a clump of peach trees, in some instances perhaps as many as 1,000 in one “orchard.” When the peaches ripen, hundreds and even thousands of Navaho flock to the place, coming from all over the reservation, like an immense flock of vultures...

Regulations required Indigenous children to attend boarding schools. They were prevented from speaking their native language and performing traditional practices. This resulted in social dislocation and loss of traditional knowledge about peach culture.

By the late 19th century, the lives of the Navajo of Canyon de Chelly and Indigenous people in general had come under the intense influence of Indian agents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The bureau charged each agent to “induce his Indian to labor in civilized pursuits,” such as agriculture. Among the agent’s duties were enforcing the prohibition of liquor, supervising the instruction of English and industrial education, and preventing departure from the reservation without a permit. Regulations required Indigenous children to attend boarding schools. They were prevented from speaking their native language and performing traditional practices. This resulted in social dislocation and loss of traditional knowledge about peach culture. The agent was also responsible for ensuring Indigenous people could farm successfully by providing instruction, tools, and materials. By the 1930s, the bureau had distributed peach trees to the Navajo within Canyon de Chelly, introducing new genotypes into the traditional gene pool.

U.S. experimentation with cross-pollinating, selecting, and budding peach varieties originated in the mid-1800s in the State of Georgia. The nascent U.S. Department of Agriculture took over the work of private peach growers in the late 19th century. This led to the commercial availability of cultivated varieties such as Elberta and Lovell. In the 20th century, U.S. government and industry-sponsored breeding programs sought to improve horticultural traits such as appearance and shelf life. They originated hundreds of new varieties. All commercial cultivars now grown in the U.S. originated in this country. Consequently, the vast majority of local landraces—fruit with uniform genetic profiles resulting from long-term domestic inbreeding—have disappeared.

Management of Canyon de Chelly National Monument remains different from most other national park units: the park and the Navajo Nation work together to protect and preserve cultural and natural resources.

In Canyon de Chelly, Navajo peach cultivation continued under the influence of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the National Park Service after designation of the national monument in 1931. The National Park Service’s interests were to protect ancient ruins and artifacts from erosion and vandalism, build roads and trails to accommodate visitors, and collaborate with Navajo canyon users. The Navajo Tribal Council successfully negotiated the right to retain ownership of the land, and Navajo people continued living in the canyons under the monument’s enabling legislation.

Management of Canyon de Chelly National Monument remains different from most other national park units; the park and the Navajo Nation work together to protect and preserve cultural and natural resources. During the 20th century, the Navajo people in the monument acquired modern cultivars and farming practices. These superseded traditional practices. Orcharding and farming gradually declined, replaced by other sources of food and livelihood.

In 1972, cultural geographer Stephen Jett from the University of California, Davis, worked with Navajo Elder Chauncey Neboyia to map orchard locations in Canyon de Chelly. Jett recorded thousands of peach trees in Canyons de Chelly and del Muerto. He noted that many trees were in a state of deterioration. And the total number of trees had greatly declined from those reported in the late 19th century.

Then history met Reagan Wytsalucy.

A Horticultural Hero Is Born

Wytsalucy grew up in Gallup, New Mexico, relatively detached from her traditional Navajo culture. A high school athlete and cheerleader, she was encouraged to study agronomy by her father. As a student of plant sciences at Utah State University, she became intrigued by the traditional Navajo peach that had all but disappeared. She learned that agricultural production among Indigenous peoples of the Southwest had declined significantly in the 20th century. Corn, beans, and squash, the three most recognized traditional food crops, remained widespread. But knowledge of traditional management of these crops had been lost. For the traditional peach, this loss was even more pronounced.

Fifty-one percent of survey participants said they traveled off-Nation to purchase groceries, where they had healthier options and lower prices. The round-trip distance to these stores was 155–240 miles.

A Diné Policy Institute 2014 report on the Navajo Nation—a land area the size of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts combined—reported only 10 full-service grocery stores. About 80 percent of the products sold in stores of the largest grocery retailer on the Navajo Nation were “junk” foods and “sweetened beverages,” which contribute to obesity and diabetes. Fifty-one percent of survey participants said they traveled off-Nation to purchase groceries, where they had healthier options and lower prices. The round-trip distance to these stores was 155–240 miles.

A 2013 study showed that about 77 percent of Navajo people had some level of food insecurity. In 2014, out of 300,000 Navajo Nation members, one in three had diabetes or prediabetes. The rate of diabetes was estimated closer to 50 percent on the Navajo Nation, vastly higher than the 8.4 percent national average. Wytsalucy was determined to be part of an effort to help Navajo people improve their nutrition and gain a source of income. She would do this by identifying and re-establishing local production of important and currently unavailable food sources.

In 2016, Wytsalucy pursued a master’s degree in plant sciences under the mentorship of Extension Fruit Specialist, Professor Brent Black, along with Professors Dan Drost, Grant Cardon, and Randy Williams. Black researches developing and adapting alternative crops. Wytsalucy focused her work on two traditional food crops: southwest peach, such as found in Canyon de Chelly, and Navajo spinach or bee plant. The Utah Department of Agriculture, the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah Humanities, and the Utah Division of History supported her research. The National Park Service and the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni tribal governments all granted her permits for collecting peach seeds and conducting oral history research with elders.

A Quest Guided by Tribal Elders

Wytsalucy set out to find traditional southwest peach orchards. She wanted to characterize their genetics, horticultural characteristics, and fruit nutritional content. She also wanted to document traditional cultural practices and beliefs. To accomplish this, she interviewed tribal elders in Canyon de Chelly and on other tribal lands.

Some elders had avoided the boarding school system as young people and remained on the reservation. Today, they are among the few people in their communities with the most knowledge of their heritage, including peach cultivation.

Wytsalucy’s research took her from Navajo Mountain in Utah to Zuni, New Mexico. It took her through Second and Third Mesas on the Hopi reservation in Arizona, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument. With the help of her father as a guide and interpreter, she spoke with Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni elders who were willing to share their peach trees and their histories. In Canyon de Chelly, they introduced Wytsalucy to 21 trees in Canyon del Muerto. They entrusted her with peach pits from traditional peach trees—those whose seeds were kept separate from modern varieties.

Wytsalucy used dendrochronology to show that the oldest trees, now dead, had lived for 80 to 100 years. The lifespan of a modern peach tree in the western U.S. is about 15 years. Her oral history interviews revealed that some elders had avoided the boarding school system as young people and remained on the reservation. Today, they are among the few people in their communities with the most knowledge of their heritage, including peach cultivation.

Image used by permission of Reagan Wytsalucy

Genetic Testing Reveals Ancient Roots

Back at Utah State University, Wytsalucy germinated some of the precious seeds, conserved others, and established a test orchard in Box Elder County in northwest Utah. She sent the first generation of new leaves that emerged on the test orchard trees to peach genetics professor Ksenija Gasic’s lab at Clemson University for DNA fingerprinting. Clemson University is a major center for peach research and one of the first institutions to map the peach genome.

Clemson University used genotyping by sequencing (GBS) genomic DNA extraction and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) technology, combined with PLINK and fastSTRUCTURE software to test the DNA of the peach plant leaves. The results were remarkable. The genotypes of the Navajo and Hopi samples were distinct from all compared modern varieties of peach.

The samples could be divided into three sub-populations. The traditional peaches from Canyon de Chelly formed one distinct group. This means the traditional peaches of the Navajo and Hopi were interrelated historically through inbreeding. Each population was so isolated they had become a genetically distinct landrace.

The traditional peach landraces had been isolated for 240 to 480 years! This was an astounding finding, considering the strong tendency of peach to hybridize through cross pollination.

Inbred populations take over six generations from a single founder individual to become genetically distinct from other populations. They take more than 10 generations for populations with more than 50 individuals. When Wytsalucy combined these inbreeding estimates with her dendrochronology findings, she determined that the traditional peach landraces had been isolated for 240 to 480 years! This was an astounding finding, considering the strong tendency of peach to hybridize through cross pollination.

A Different Nutritional Profile

There were other intriguing results from Wytsalucy’s tests. When she compared traditional peaches from Navajo Mountain with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s standard peach reference, she found the Navajo Mountain peach to be higher in carbohydrates, fat, and calories. It was lower in protein but more than 30 percent higher in calcium and potassium than modern varieties.

The Traditional Way of Horticulture

Wytsalucy’s ethnographic research revealed even more information. Her great grandfather, Hoskinini, was one of the Navajo people who avoided capture by the U.S. Army in 1864, taking refuge in Jayi Canyon near Navajo Mountain. Hoskinini and fellow fugitives cultivated peach trees and other crops there, and they rounded up abandoned livestock to form herds. Navajo people continue cultivating traditional peach trees in Jayi Canyon to this day. Wytsalucy took samples from these varieties for her research.

Wytsalucy’s interviews with Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni elders showed that traditional peach cultivation had sowing and germination techniques similar to other traditional crops. But they had different approaches to irrigation. The Hopi people did not irrigate. The elders were opposed to fruit thinning to avoid ending life prematurely. They only pruned to remove dead wood. They used berms mounded around the trees to retain water and encourage suckering. The seasonal cycles of peach blossoms and fruit ripening coincided with spiritual ceremonies, and orchards were ceremonial places. Tribes created shrines in peach orchards and made offerings for the peaches to thrive and continue nourishment of their people. Ceremonial chants featured prayers for an abundant peach crop in the new year.

Navajo Elder Mae Gui was born in 1936. With the help of her niece, Sylvia Watchman, who translated, Gui talked to Wytsalucy about replanting new peach trees in Canyon del Muerto throughout her life. Demonstrating how to crack a Navajo peach pit open to remove the seed for planting, Gui explained that they planted peach seeds where ash is thrown out of the house. This was to provide the nutrition needed to make the seedlings strong. “They used to [start] them during the month of November,” said Gui, “and then during springtime, they will grow out in a bunch. And then they always look for places where it’s good for the peaches to grow out.” Gui’s orchard is one of the last remaining healthy orchards in Canyon del Muerto, along with those planted by Elders Katherine Paymela and Francis Drapper.

"Quite a while back, there was a lot of rain that we received, and we didn’t live this drought world back then, so there was plenty of water."

In Jayi Canyon near Navajo Mountain in Utah, people used a different germination method, a local adaptation to different growing conditions. They sowed the peach seed inside the pit, rather than first removing it from the seed coat. This was important because it improved the germination rate. The Tsinnajinni siblings, Rocky, born in 1941, and Sarah, born 1954, told Wytsalucy if she wanted to produce a stronger tree, she shouldn’t crack the peach pit before planting.

The Navajo elders of Canyon del Muerto recalled that their grandparents managed the peach orchards without supplemental irrigation, relying only on precipitation. “Quite a while back, there was a lot of rain that we received,” Paymela explained, “and we didn’t live this drought world back then, so there was plenty of water. We have spring waters here and there we didn’t really use. We did use them when we needed them. But now, with the drought, even our spring waters are kind of low.”

Unlike Hopi and Zuni people, Navajo elders were skeptical that their traditional peaches came from the Spanish. Wytsalucy’s father, Roy Talker, who was born in 1958, recounted that his grandfather always said, “The peaches were there [in the canyons] from a long time ago” and were not of Spanish origin.

Recognizing how privileged she was to receive this information, Wytsalucy shared her transcripts and research findings with the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni Tribes to help them preserve their heritage.

A Promising Trait

After receiving her master’s degree in 2019, Wytsalucy became an assistant professor with the Utah State University Extension in San Juan County. She has continued her horticultural research on traditional peaches, studying their adaptation to heat and drought. Her recent work shows that traditional peaches are more tolerant of drought compared to the modern Lovell peach, particularly in their rate of recovery from periods of drought stress.

National Park Orchards Are Crucial

Chatting recently with me about her future plans, Wytsalucy said she wants to create demonstration orchards of traditional peaches for educational purposes. She wants to be part of a sustainable farming movement in Indigenous communities. She is collaborating with the National Park Service, the Navajo Nation, and the farming community on a plan to protect and restore the traditional peach in Canyon de Chelly. “This effort is complemented by years of invasive exotic plant removal in the canyons,” said Park Integrated Resources Manager Keith Lyons. “More than 900 acres of Russian Olive and Tamarisk removal have enhanced environmental quality, increased water availability, and improved growing conditions for farmers."

The agency recognizes historic orchards and their heirloom germplasm as cultural resources that should be preserved and perpetuated.

Wytsalucy’s work is an inspiration for many, including the National Park Service. The agency recognizes historic orchards and their heirloom germplasm as cultural resources that should be preserved and perpetuated. The form of orchards and their respective fruit trees have evolved considerably in the United States since the 1600s. The National Park Service attempts to preserve the historic authenticity of orchards within significant cultural landscapes. Through the remarkable information revealed by Wytsalucy’s research and working with the Navajo of Canyon de Chelly, the National Park Service is supporting preservation of the traditional peach and the Navajo people’s heritage.

About the author

Susan Dolan is the Bureau Historical Landscape Architect for the National Park Service. Her academic background is in horticulture and landscape architecture.