Last updated: August 15, 2022

Article

Horace Albright's National Park Service Legacy

I'm not an organization man. I like to do things in the field, not fiddle-faddle around an office, pushing papers and digging around in details. When you leave, I would have nobody to take care of these things, and I simply cannot tackle them by myself.

—Stephen Mather to Horace Albright, from the book Creating the National Park Service: The Missing Years

How do you create an agency to manage national parks from scratch? It certainly helps to have an energetic, fast-talking promoter with the social ties to get the job done, but that is only half of it. You also need someone more patient; someone who can be persuasive in government structure; and is just as effective at talking to congressional delegates as he or she is writing policy and memos. In the history of the National Park Service, this methodical administrator was Horace M. Albright.

Start of the Career

Horace Albright was born in 1890 in California. In 1913, Albright graduated from the University of California, Berkeley and moved to Washington, DC to begin working as a clerk for the Secretary of the Interior. In the department, he became interested in issues facing national parks, and in 1915 the parks became his primary focus. That year the Department of the Interior became interested in hiring businessman and conservationist Stephen Mather to head the affairs of national parks. Mather was interested in the job, but skeptical about government work. To alleviate Mather’s fears, he was introduced to Horace Albright. Mather and Albright saw that they were well-suited for each other. Mather only agreed to join the department if Albright assisted him.

Assisting Stephen Mather

For decades there had been major problems with management of national parks. Around 1910 it was clear that many of these issues stemmed from lack of centralized management. For example, some parks were policed by the military, others were completely under civilian control, a few had a volunteer custodian, and others were nearly unmanaged. This patchwork of park management was leading to the deterioration of park resources. The solution to these issues was becoming clear; the parks needed their own federal agency to oversee them. Stephen Mather was seen as the person who could make this happen, but he needed someone to balance him out. That person was Horace Albright.

For two years Albright’s attention was focused on working with Mather. To accomplish their goal of a new agency, they began getting supporters who would work for the cause. They engaged auto clubs, magazine writers, railroads, congressmen, and nearly anyone else who would benefit from a stronger park system. Mather was as expected: a passionate, energetic leader who had valuable political and personal connections. Albright continually translated Mather’s ideas into something more suited to the constraints they were faced with, as well as thinking of innovative paths forward on his own. Their strategies proved effective, and on August 25, 1916 the act creating the National Park Service was signed into law.

Acting Director

Soon after the National Park Service was established, Albright had to prove himself even more. In early January 1917, Stephen Mather was hospitalized from what was most likely a severe lapse of bipolar depression. Mather was appointed director of the National Park Service, but his condition left him unable to lead the new agency until mid-1919. Horace Albright had to act as director during this time. This was an essential period for strong leadership. Even though the agency was established, its continued existence was not guaranteed. Under Albright’s leadership, the agency was able to prove its worth even through the tight budgets of World War I.

NPS

Superintendent of Yellowstone

When Stephen Mather returned to work, Albright was debating his future and was even considering leaving the government. He felt that he needed a job that was more stable for his family. For years he had spent much of his time away from his wife, Grace, and now he had a baby on the way. At the same time, he really cared for the agency he helped create and knew that Mather needed his help. After speaking with Grace and Mather, Albright decided becoming superintendent of Yellowstone was the best option for his skills and his family. Becoming superintendent had all the answers to his problems: he could easily be with his family, help Mather when needed, especially during the winter off season, and use Yellowstone to demonstrate to other superintendents how a National Park Service-managed site should operate.

On July 15th, 1919, the Albright family moved into the superintendent’s house in Yellowstone’s Mammoth Hot Springs. He would stay in the position for nearly a decade. As superintendent, Albright was open to new programs and management techniques. Many of these programs became the foundation of the major functions of national parks today. For example, he approved the first government information bureau and hired some of the first ranger naturalists of the National Park Service. This evolved into the functions performed by interpretive rangers today. He also was instrumental in creating design and building standards for park buildings. It was during his tenure that some of the first rustic architecture the agency is known for was incorporated into the park’s buildings. The trailside museums proposed by Albright, some of which still stand and serve visitors in various capacities, reflect this style and were examples for many buildings that were constructed throughout the country during the Great Depression.

During Albright’s superintendence, he also continued to serve the agency as a whole. Aside from assisting Mather, he was instrumental in inspecting and securing potential national park units. The most famous of these was his work enlarging Grand Teton National Park. Ultimately, Albright convince John D. Rockefeller Jr. to help with securing land in the valley of Jackson Hole. Rockefeller set up a land company to buy land in the valley. Although this process was controversial, eventually Rockefeller was able to donate that land to the government and in time the property was added to the park. Aside from the Tetons, Albright also help Mather bring national parks to the East in the form of parks like Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains.

Second Director of the National Park Service

In 1929, Stephen Mather suffered a stroke that made him unable to continue as director. Horace Albright was selected as Mather’s successor. As director, Albright’s most lasting legacy was adding historic sites to the agency’s management. For years Albright imagined an expanded role for the NPS to manage the nation’s historic sites. After speaking with newly elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt about this idea, Roosevelt reorganized the Departments of the Interior, Agriculture, and War. As a result, the National Park Service gained Agriculture-managed monuments and War Department historic sites. In all, the 1933 Reorganization led to the Service gaining 57 new units. This made it clear that the National Park Service would be a system of units that included historic areas and stories.

Image credit NPS

Departure from the National Park Service and Later Years

After attaining his major goals, Albright resigned from the National Park Service in 1933. He then took a position in the United States Potash Company. He retired from the company in 1956. Although he went into the private sector, Albright was always interested and involved in the affairs of national parks. He was even awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980 for his involvement with the creation of the National Park Service. Albright died in 1987.

During his time serving the national parks, Horace Albright created an impressive legacy. As co-creator of the Service, first National Park Service director of Yellowstone, and director of the agency, Albright proved that his skills as a patient, innovative administrator were just what the parks needed.

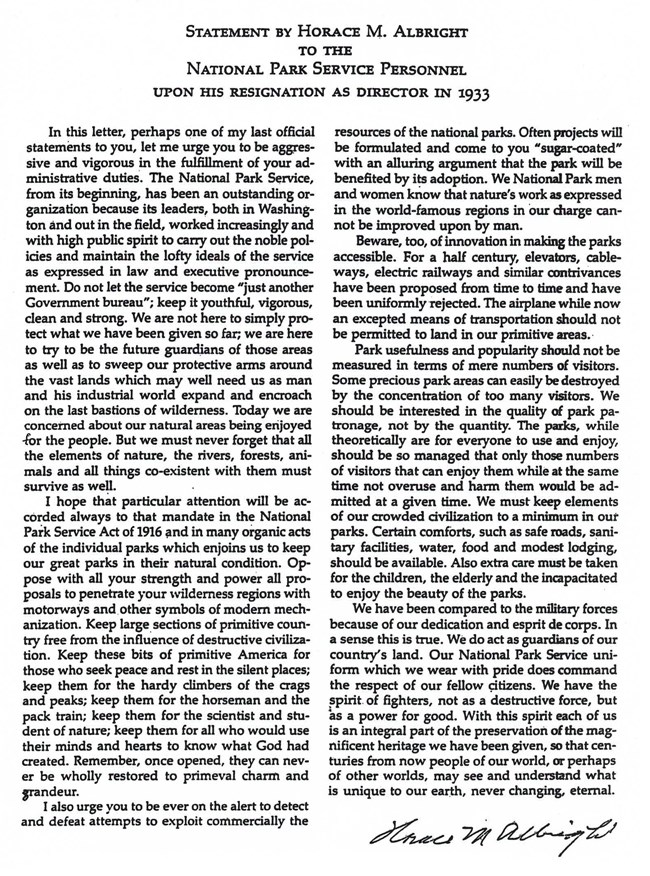

In this letter, perhaps one of my last official statements to you, let me urge you to be aggressive and vigorous the fulfillment of your administrative duties. The National Park Service, from its beginning, has been an outstanding organization because its leaders, both in Washington and out in the field, worked increasingly and with high public spirit to carry out the noble policies and maintain the lofty ideals of the service as expressed in law and executive pronouncement. Do not let the service become "just another Government bureau"; keep it youthful, vigorous, clean and strong. We are not here to simply protect what we have been given so far; we are here to try to be the future guardians of those areas as well as to sweep our protective arms around the vast lands which may well need us as man and his industrial world expand and encroach on the last bastions of wilderness. Today we are concerned about our natural areas being enjoyed for the people. But we must never forget that all the elements of nature, the rivers, forests, animals and all things co-existent with them must survive as well.

I hope that particular attention will be accorded always to that mandate in the National Park Service Act of 1916 and in many organic acts of the individual parks which enjoins us to keep our great parks in their natural condition. Oppose with all your strength and power all proposals to penetrate your wilderness regions with motorways and other symbols of modern mechanization. Keep large sections of primitive country free from the influence of destructive civilization. Keep these bits of primitive America for those who seek peace and rest in the silent places; keep them for the hardy climbers of the crags and peaks; keep them for the horseman and the pack train; keep them for the scientist and student of nature; keep them for all who would use their minds and hearts to know what God had created. Remember, once opened, they can never be wholly restored to primeval charm and grandeur.

I also urge you to be ever on the alert to detect and defeat attempts to exploit commercially the resources of the national parks. Often projects will be formulated and come to you "sugar-coated" with an alluring argument that the park will be benefited by its adoption. We National Park men and women know that nature's work as expressed in the world-famous regions in our charge cannot be improved upon by man.

Beware, too, of innovation in making the parks accessible. For a half century, elevators, cableways, electric railways and similar contrivances have been proposed from time to time and have been uniformly rejected. The airplane while now an excepted means of transportation should not be permitted to land in our primitive areas.

Park usefulness and popularity should not be measured in terms of mere numbers of visitors. Some precious park areas can easily be destroyed by the concentration of too many visitors. We should be interested in the quality of park patronage, not by the quantity. The parks, while theoretically are for everyone to use and enjoy, should be so managed that only those numbers of visitors that can enjoy them while at the same time not overuse and harm them would be admitted at a given time. We must keep elements of our crowded civilization to a minimum in our parks. Certain comforts, such as safe roads, sanitary facilities, water, food and modest lodging, should be available. Also extra care must be taken for the children, the elderly and the incapacitated to enjoy the beauty of the parks.

We have been compared to the military forces because of our dedication and esprit de corps. In a sense this is true. We do act as guardians of our country's land. Our National Park Service uniform which we wear with pride does command the respect of our fellow citizens. We have the spirit of fighters, not as a destructive force, but as a power for good. With this spirit each of us is an integral part of the preservation of the magnificent heritage we have been given, so that centuries from now people of our world, or perhaps of other worlds, may see and understand what is unique to our earth, never changing, eternal.

Signed / Horace M Albright