Last updated: October 23, 2022

Article

Hooker Takes Command

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

In the wake of the defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg, some Federal officers openly questioned Burnside’s ability to command the army. This internal discontent overflowed in late December when Brigadier Generals John Newton and John Cochrane travelled to Washington and used political connections to secure a meeting with Lincoln himself. Newton and Cochrane, claiming that they only had the best interests of the Army of the Potomac in mind, warned Lincoln that any movement Burnside was planning was doomed because the army no longer had faith in their commander.

When Burnside learned of this meeting, he was furious. No one, however, angered Burnside more than Major General Joseph Hooker.

From the time Burnside assumed command in November, Hooker had not been shy about sharing his opinions regarding Burnside’s ability (or inability) as army commander. Those opinions were strengthened by the failure of the Mud March. As weary Federal soldiers fumbled back into their camps, Hooker spoke loudly and often to newspaper reporters about his frustrations. Burnside reached his breaking point on January 23, 1863, and he “let loose the floodgates of his resentment.”1

On Jan. 23, Burnside wrote to Lincoln, “I have prepared some very important orders, and I want to see you before issuing them.” Burnside requested to meet alone with Lincoln after midnight. In Washington, Burnside showed the President a draft of General Orders No. 8, that outright fired or sent away from the army the officers whom Burnside felt were the ringleaders of insubordination.2

HDQRS. ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

January 23, 1863.

I. General Joseph Hooker, major-general of volunteers and brigadier-general U.S. Army, having been guilty of unjust and unnecessary criticisms of the actions of his superior officers, and of the authorities, and having, by the general tone of his conversation, endeavored to create distrust in the minds of officers who have associated with him, and having, by omissions and otherwise, made reports and statements which were calculated to create incorrect impressions, and for habitually speaking in disparaging terms of other officers, is hereby dismissed the service of the United States as a man unfit to hold an important commission during a crisis like the present, when so much patience, charity, confidence, consideration, and patriotism are due from every soldier in the field. This order is issued subject to the approval of the President of the United States.

II. Brig. Gen. W. T. H. Brooks, commanding First Division, Sixth Army Corps, for complaining of the policy of the Government, and for using language tending to demoralize his command, is, subject to the approval of the President, dismissed from the military service of the United States.

III. Brig. Gen. John Newton, commanding Third Division, Sixth Army Corps, and Brig. Gen. John Cochrane, commanding First Brigade, Third Division, Sixth Army Corps, for going to the President of the United States with criticisms upon the plans of their commanding officer, are, subject to the approval of the President, dismissed from the military service of the United States.

IV. It being evident that the following-named officers can be of no further service to this army, they are hereby relieved from duty, and will report, in person, without delay, to the Adjutant-General, U.S. Army: Maj. Gen. W. B. Franklin, commanding left grand division; Maj. Gen. W. F. Smith, commanding Sixth Corps; Brig. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis, commanding Second Division, Ninth Corps; Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero, commanding Second Brigade, Second Division, Ninth Army Corps; Brig. Gen. John Cochrane, commanding First Brigade, Third Division, Sixth Corps; Lieut. Col. J. H. Taylor, assistant adjutant-general, right grand division.

By command of Maj. Gen. A. E. Burnside:LEWIS RICHMOND,

Assistant Adjutant-General.3

Library of Congress

Burnside told the president that if these orders were not accepted, he would resign from the army. Lincoln thought the matter over and chose to relieve Burnside of command from the Army of the Potomac, but would not remove him from the army completely. Rather, Burnside was shuffled to an administrative post in the Department of the Ohio. Burnside later retook command of the Ninth Corps and led it during the Knoxville and Overland campaigns.

On January 26, the change in command was formalized. In his goodbye to the army, Burnside wrote to the soldiers, “be true in your devotion to your country and to the principles you have sworn to maintain.”4

Meanwhile, Lincoln appointed Major General Joseph Hooker to command. Hooker was a West Point educated military officer who had resigned from the military in 1853. Upon the outbreak of war, Hooker traveled from California to Washington and lobbied for a position in the US Army. In August 1861, he finally received the command he sought. Hooker had performed well during the Peninsula Campaign and at Antietam, and fast became one of the most respected leaders in the army.

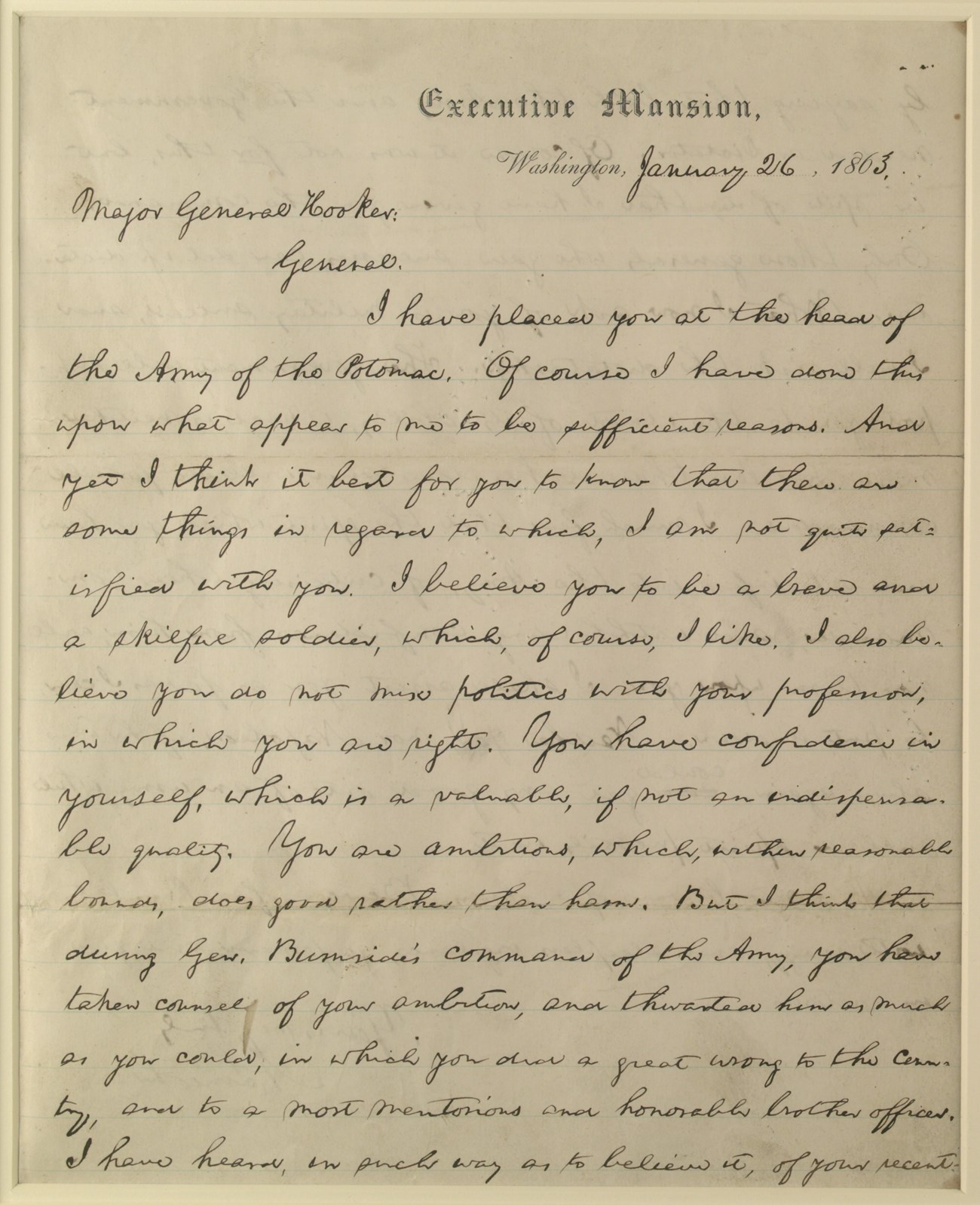

Despite having a solid reputation as a military leader, Hooker's ambition was known to get the better of him. Lincoln made his reservations known to Hooker upon granting him command:

Executive Mansion

Washington, January 26, 1863Major General Hooker:

General.

I have placed you at the head of the Army of the Potomac. Of course I have done this upon what appear to me to be sufficient reasons. And yet I think it best for you to know that there are some things in regard to which, I am not quite satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and a skillful soldier, which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not mix politics with your profession, in which you are right. You have confidence in yourself, which is a valuable, if not an indispensable quality. You are ambitious, which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm. But I think that during Gen. Burnside's command of the Army, you have taken counsel of your ambition, and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country, and to a most meritorious and honorable brother officer. I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship. The government will support you to the utmost of it's ability, which is neither more nor less than it has done and will do for all commanders. I much fear that the spirit which you have aided to infuse into the Army, of criticizing their Commander, and withholding confidence from him, will now turn upon you. I shall assist you as far as I can, to put it down. Neither you, nor Napoleon, if he were alive again, could get any good out of an army, while such a spirit prevails in it.

And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.

Yours very truly

A. Lincoln5

Library of Congress

For his part Hooker, treasured this letter. Journalist Noah Brooks recalled visiting camp and being shown the letter by Hooker himself. Hooker then told proudly Brooks, “That is just such a letter as a father might write to his son. It is a beautiful letter, and, although I think he was harder on me than I deserved, I will say that I love the man who wrote it.”6

As Hooker assumed command, he knew the army’s morale was nearly bottomed out. Hooker had his work cut out for him during this winter of discontent and he quickly set to the task transforming the Army of the Potomac.