Article

Hoodoo in St. Louis: An African American Religious Tradition

Slavery Images

Hoodoo (not to be confused with Voudou) is a spiritual religious tradition created by enslaved African Americans in the United States and inspired by Central and West African religious practices. The practices include herbal healing, veneration of African ancestors, counterclockwise circle dancing (Ring Shout), water immersion, sacred music, spirit possession, divination, and using charms for spiritual protection against physical harm and conjure. Many of these Central and West African religious practices were brought to North America during the transatlantic slave trade. Enslaved Africans were often forced to become Christians upon arrival in North America. The synchronization of African practices with the Christian religion created Hoodoo among enslaved African Americans. Slave codes did not allow large gatherings of free or enslaved Blacks, and it was a crime for African Americans to practice traditions from Africa. As a result, some Hoodoo practices were hidden in African American churches, creating a unique brand of Christianity that fused African traditions that was called Afro-Christianity, or African American Christianity. The Hoodoo religion during slavery included religious practices from various African cultural groups, including the Odinani religion of the Igbo people, the Yoruba and Vodun religions of the Fon and Ewe people, and a Bantu-Kongo tradition in Central Africa. All these African religious traditions blended and fused with Christianity on slave plantations, creating a unique spiritual tradition practice by enslaved African Americans and their descendants. After the Civil War, many of these African religious practices survived in Hoodoo and became a spiritual practice that continues in African American communities today.

During slavery, the words “conjure” and “Voudoo” were used to describe the conjure practices of enslaved and free blacks. Hoodoo practices documented by former slaves will describe Hoodoo as either conjure or Voudoo. The earliest known use of the word Hoodoo to describe African American conjure was around 1870 in a book titled Seership the Magnetic Mirror, written by Black American occultist Paschal Beverly Randolph. Randolph believed the word Hoodoo derived from an African dialect, because he traveled to Africa and studied African religions. Today in the African American community, Hoodoo is known by other names such as root work and conjure.

Wikimedia Commons

Hoodoo in St. Louis

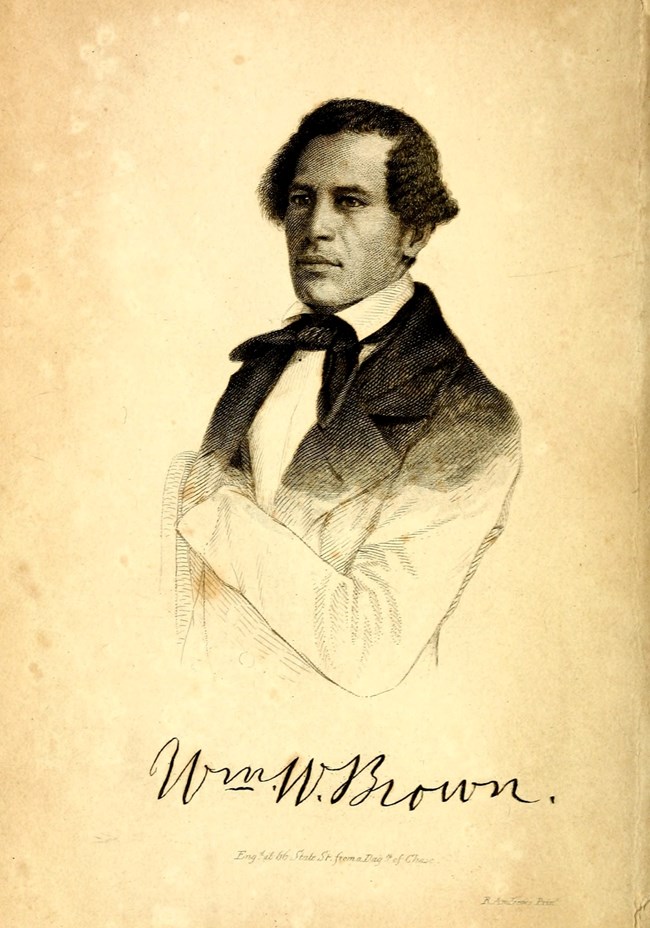

William Wells Brown (circa 1814-1884) was a formerly enslaved man and an abolitionist who documented Hoodoo practices of enslaved people in St. Louis in two of his books. Brown was born enslaved in Kentucky. In 1827 Brown’s enslaver, Dr. John Young, moved near St. Louis, Missouri, and established a small farm. Dr. Young hired out Brown to work in the city of St. Louis for steamboat captains and local merchants. During his years enslaved in St. Louis, Brown saw conjure practices of enslaved people that he documented years later in his autobiographies after he escaped from slavery on the Underground Railroad. In 1849, Brown published Narrative of William W. Brown, An American Slave. Written by Himself. In the book, Brown wrote that he saw an enslaved man named Frank who was a fortune-teller. Brown spoke to Frank to know if his plan for escape from slavery on the Underground Railroad would lead to his freedom. Brown wrote:

“I should have stated, that, before leaving St. Louis, I went to an old man named Frank, a slave, owned by a Mr. Sarpee. This old man was very distinguished (not only among the slave population, but also the whites) as a fortune-teller….I found Uncle Frank seated in the chimney corner, about ten o'clock at night. As soon as I entered, the old man left his seat. I watched his movement as well as I could by the dim light of the fire. He soon lit a lamp, and coming up, looked me full in the face, saying, ‘Well, my son, you have come to get uncle to tell your fortune, have you?’ ‘Yes,’ said I. But how the old man should know what I came for, I could not tell. However, I paid the fee of twenty-five cents, and he commenced by looking into a gourd, filled with water. Whether the old man was a prophet, or the son of a prophet, I cannot say; but there is one thing certain, many of his predictions were verified. I am no believer in soothsaying; yet I am sometimes at a loss to know how Uncle Frank could tell so accurately what would occur in the future. Among the many things he told was one which was enough to pay me for all the trouble of hunting him up. It was that I should be free! He further said, that in trying to get my liberty I would meet with many severe trials. I thought to myself any fool could tell me that!”

Brown recorded more Hoodoo practices in St. Louis in his 1880 book, My southern home, or, The South and its people. Brown recalled more events from when he was enslaved in Missouri as a young adult. One night in St. Louis, Brown saw what he called a secret Voudoo ceremony among enslaved people. According to Brown’s written account, enslaved people gathered secretly at midnight and sat around a cauldron speaking in different languages; this can be interpreted as the enslaved were probably speaking in their native African languages, because in his book Brown wrote that the enslaved were “conversing in different tongues.” There was a Voudoo queen with a magic wand, and a cauldron was placed on the ground and animal parts such as frogs, lizards, snakes, dog livers, and beef hearts were thrown into the cauldron. During this ritual, Brown recorded that they danced in a circle to where the dance became more frantic, and it seemed some of the participants were probably possessed by African spirits. Although Brown described this ritual as Voudoo it may be a regional style of Voudoo/Hoodoo in St. Louis. This is an example how Hoodoo in the slave community derived from West and Central African religions.

Brown wrote another account of an enslaved African named Dinkie who was known in the slave community as the Goopher King and King of Voudoos on Poplar Farm owned by Mr. Gaines in St. Louis County. Dinkie was described by Brown as a “full-blooded African.” Brown wrote that Dinkie was well versed in voudooism, goophering, and fortune-telling. The practice of goophering is using goopher dust. Goopher dust is a powder used in Hoodoo for protection and sometimes “to fix a person.” It is made of various herbal and other ingredients and ground into a powder. The practice of goopher dust comes from Central Africa among the Bakongo people, and the word goopher, according to scholars, comes from the Kongo word “Kufwa, meaning to die.” Dinkie used goopher dust on an overseer named Grove Cook at Poplar Farm who planned to whip him because he refused to work in the field. To protect himself from a whipping Dinkie used conjure. “Dinkie closely inspected the snake's skin around his neck, the petrified frog and dried lizard, in his pockets, and had rubbed himself all over with goopher.” After this, Dinkie spoke to a spirit and asked that spirit to attack the overseer.

According to Brown this practice worked. Dinkie rarely worked in the field, and the overseer and Mr. Gaines never assaulted Dinkie. To a certain extent this process made Dinkie his own master, feared and respected by some whites in St. Louis. Even some enslaved people feared him. Dinkie had a reputation on Poplar Farm as an experienced conjurer that whites in St. Louis visited in order to have their fortune told. For these reasons, Brown believed the practice of conjure (Hoodoo) was an established institution in slave communities.

National Park Service

Finding Hoodoo at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site

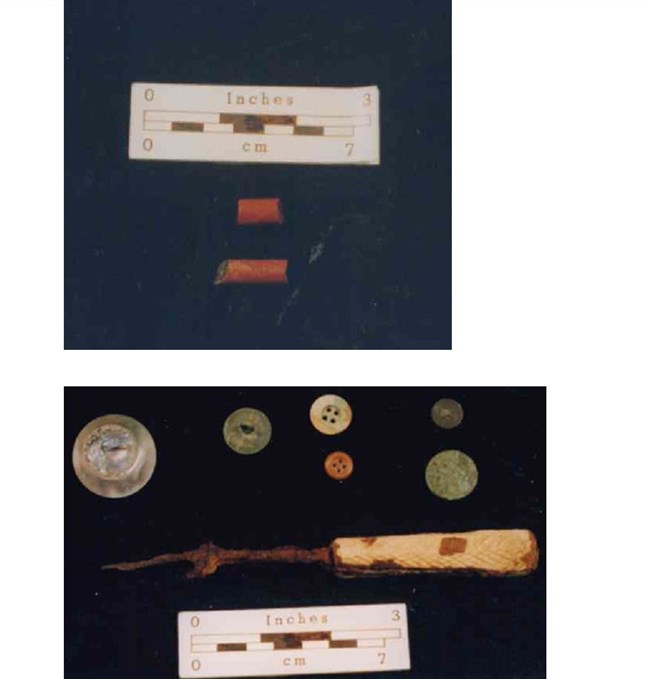

Another example of archeological evidence showed a fusion of African traditions on slave plantations throughout the United States and at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site in St. Louis. Archeologists found Central African minkisi bundle practices on various plantations that mixed with West African spirituality. The creation of minkisi involves creating cloth bundles with various items and burying the bundles underneath the floorboards in houses or hiding minkisi bundles near entrances to doorways or chimneys to conjure specific results. Minkisi plural and nkisi singular is when a spirit inhabits an object created by a conjurer. Nkisi and minkisi are spirit containers. The items found inside minkisi bundles were beads, crab claws, military buttons, a peach pit, crystals, seashells, iron, and sharp projectile points. Each item has a spiritual meaning. In West and Central Africa beads bring spiritual protection from harm and are fertility charms for women worn around the waist for fertility. These practices were done in secret by the enslaved for protection from slaveholders and conjure.

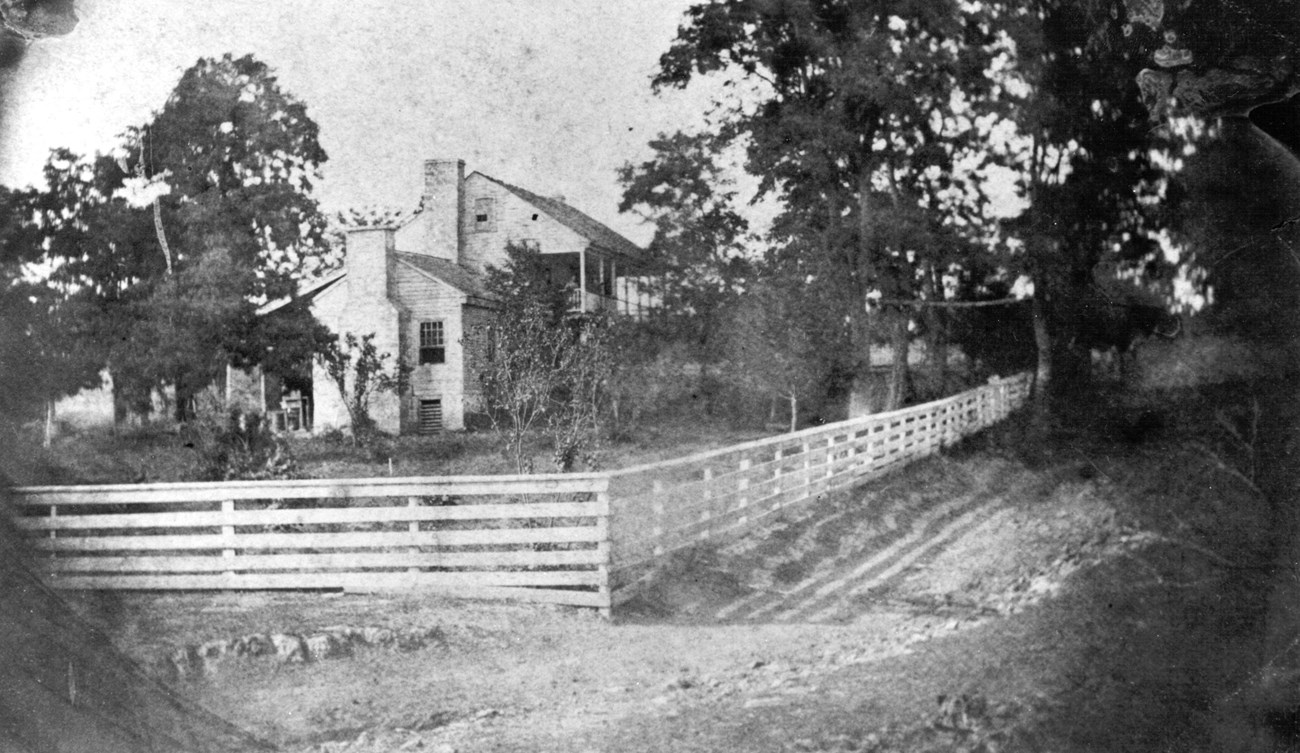

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site is located in St. Louis and is the historic home of the Dent and Grant families, who owned White Haven for most of the nineteenth century. This historic site tells the story of Civil War general and future President Ulysses S. Grant, who met and married Julia Dent at White Haven. Julia Dent’s father Frederick Dent supported slavery and enslaved 30 African Americans before the Civil War. White Haven is a historic property that consists of the houses owned and lived by the Dent and Grant family, includes the winter and summer kitchens, and slave cabins.

At Ulysses S. Grant NHS, archeologists and historians found two minkisi bundles. They estimate the conjure bundles were Bakongo in origin by their design, and numerous buttons with four holes were found inside the bundles. The four-hole buttons were interpreted to correspond to the Bakongo’s peoples sacred symbol the Kongo cosmogram also called dikenga and the Yowa cross. The Kongo cosmogram means in Central Africa reincarnation of the soul. The four points of the cosmogram means birth, life, death, and rebirth. This symbol is utilized in Hoodoo to bring spiritual protection and influenced the ring shout. In addition, African beads were worn by enslaved women at Grant historic site as charms and to maintain an African identity. Silver dimes were found in the Winter Kitchen. Silver dimes are used in Hoodoo as protective charms. Other items found in minkisi bundles at Grant historic site were the same items found in similar conjure bundles on other slave plantations.

National Park Service

More spiritual practices of enslaved African Americans at Grant historic site were prayer in nature and Christmas and Easter festivals in the slave community. It was recorded by Julia Dent, an enslaved man named Old Bob would go into the woods and pray. Julia said that sometimes Bob “would get religion.” “He would go away down in the meadow by the big walnut trees nearly half a mile off and pray and sign so we could hear him distinctly on our piazza [at White Haven].” “Old Bob used the power of nature and the power spiritual hymns to find inner peace while living in a world dominated by the oppressiveness of slavery.”

Julia Dent discussed in her memoir enslaved Christmas and Whitsuntide festivals at White Haven. “I call back the memory of those Christmas holidays and Whitsuntide festivals, the weddings of those poor people (they often got married without getting divorces), the fine suppers the master and mistress always gave them on these occasions; then the corn shuckings of which they also made a feast; they would pile the freshly gathered corn in a rick ten or twelve feet high and, it seemed to me, a hundred long. They would invite all of the colored people from far and near, and, after greetings had passed and they had something to drink, they would gather around, sometimes two or three hundred strong, and word, song, and chorus would begin, and as I see the fire lighting up the weird company and hear the wild, plaintive, and, to me, pathetic music, it brings up a most pleasant memory.”

Slavery Images

These practices in St. Louis did not die during slavery but continued after emancipation. It was recorded that an Igbo man from Nigeria, a country in West Africa, who moved to the United States from Hamburg, Germany in 1920 named Samuel Kojoe Pearce was arrested in St. Louis in 1927 on charges for “using mails to defraud.” Samuel Kojoe Pearce (also known as Dr. Pearce) made money by making and selling potions, powders, charms and shipping these products by way of mail order to African Americans. African Americans bought these items in hopes they would provide them a new job, protection, and healing. During the Jim Crow era where racial segregation was legal, some African Americans turned to Hoodoo to obtain employment, protection from law enforcement and racial terror in hopes that spiritual works would provide them a better life under oppression from racial discrimination. African Americans also used Hoodoo to treat illnesses using herbal medicines. African Americans made treated illnesses using herbal teas and creating health tonics. These African practices and beliefs continue in African American communities today and are called Hoodoo, conjure and root work. However, by the twentieth century hoodoo was appropriated by people who were not of African descent and was used to make a profit from African Americans spiritual traditions.

Further Reading

Boson, Crystal Michelle. Digital Loa and Faith You Can Taste: Hoodoo in the American Imagination. Dissertation. University of Kansas Digital Loa and Faith You Can Taste: Hoodoo in the American Imagination (ku.edu)

Brown, William W. My Southern Home, or the South and its People. 1880. William Wells Brown, 1814?-1884. My Southern Home: or, The South and Its People. (unc.edu)

Brown, William W. Narrative of William W. Brown, An American Slave. Written by Himself. 1849. William Wells Brown, 1814?-1884. Narrative of William W. Brown, an American Slave (unc.edu)

Chireau, Yvonne P. Black Magic Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition. 2006

Coggswell, Gladys C. Stories from the Heart Missouri’s African American Heritage. 2009

Donald, Katrina H. Mojo Workin: The Old African American Hoodoo System. 2013

Grant, Julia Dent. Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant. 1975

Kail, Tony. Stories of Rootworkers & Hoodoo in the Mid-South. 2019

Old Bob. Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site. Old Bob (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

Pyatt, Sherman E. and Alan Johns. A Dictionary and Catalog of African American Folklife of the South. 1999

Raboteau, Albert. Slave Religion: The Invisible Institution in the Antebellum South. 1978

Randolp, Paschal B. Seership the Magnetic Mirror. 1870 Seership, the Magnetic Mirror : Randolph, Paschal Beverly

Richer, Jeffrey and Karin Roberts. Slavery and Slave-related Artifacts at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site. 2017

“Spiritual Practices in the Lowcountry.” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative. A Digital History Project hosted by the Lowcountry Digital Library at the College of Charleston. Spiritual Practices in the Lowcountry · Hidden Voices: Enslaved Women in the Lowcountry and U.S. South · Lowcountry Digital History Initiative (cofc.edu)

Thompson, Robert F. Flash of the Spirit African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy. 1983

Wilson, Khonsura. “Nkisi West-Central Lore.” Encyclopedia Britannica Nkisi | west-central African lore | Britannica

“VOODOO DOCTOR' INDICTED.; Negro Charged With Using Mails to Sell 'Charms.'” The New York Times. July 1, 1927. VOODOO DOCTOR' INDICTED.; Negro Charged With Using Mails to Sell 'Charms.' - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

“National Affairs: Medicine Man.” In Time Magazine. July 11, 1927 National Affairs: Medicine Man - TIME