Last updated: May 3, 2022

Article

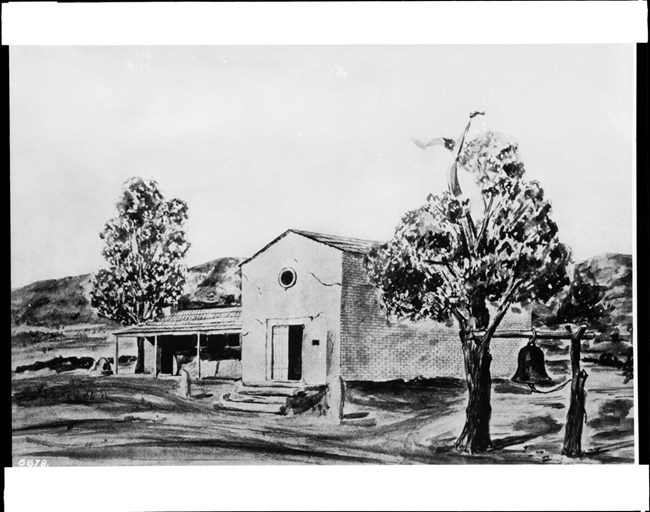

Hipólito Espinosa, the Old Spanish Trail

Image/Public Domain

Hipólito Espinosa – Old Spanish Trail[1]

By Angela Reiniche

Hipólito Espinosa was among the first colonists to arrive in Alta California from New Mexico via the Old Spanish Trail, having already spent years as a horse wrangler for trading caravans along the trail.[2] Like many who emigrated from New Mexico over the Old Spanish Trail, Espinosa had some advance knowledge of California before moving his family there. In August of 1832, he traveled with Santiago Martín and fourteen other men from Abiquiú to trade woolen goods for horses and mules.[3] Once in California, Espinosa had to obtain a license—valid only for thirty days—to transport trade goods between Los Angeles and Monterey.[4]

Espinosa worked as a driver for numerous trade caravans that traveled annually on the Old Spanish Trail.[5] Doing this earned him the money that was later necessary to finance the emigration of several families from Abiquiú to the San Bernardino Valley, many of them genízaros—Indigenous people brought to New Mexico as captives and eventually assimilated into colonial Spanish society. As was the case in New Mexico, the settlements founded by these emigrants who made their way to Alta California via the Old Spanish Trail served as buffer communities. The trail provided an opportunity for genízaro families to obtain (and farm) land on the margins of larger ranchos in exchange for their collective ability to defend it from regular attacks and livestock raiding.[6]

In 1838 Espinosa and respected guide Lorenzo Trujillo led a small scouting party ahead of the annual caravan from Abiquiú to California. Upon their arrival, they negotiated with Antonio Lugo, who offered them land if they would help protect his grant from marauders.[7] Espinosa and his family eventually accepted, making their home on Lugo’s land in a pueblo that would become known as Politana (derived from his given name). Trujillo also settled on Lugo’s land and, promising that he knew of other Abiquiú families who wanted to make the journey, Trujillo and his sons started building adobe homes for other New Mexican settlers.[8] Trujillo and Espinosa joined the return caravan to New Mexico in the spring of 1842; in August of that year, they guided a dozen families and numerous pack mules to their settlement in California. When they arrived in November, the families—about forty individuals total—moved into their new homes on the Lugo grant. Trujillo’s sons, who had stayed behind to finish the homes, had also grown vegetables to aid their fellow New Mexicans’ transition over the winter of 1842–1843.[9]

At Politana, Espinosa and his family produced crops that they sold to New Mexican traders arriving in California along the Old Spanish Trail. Authorities required caravans entering California to wait just below Cajon Pass—the gateway to the San Bernardino Valley—for inspection.[10] While waiting, New Mexican travelers feasted, “consumed liberal amounts of aguardiente,” and shared stories of their travels and news from their former homes. A contemporary observer noted that “[Espinosa’s] farm was the first friendly settlement they encountered on arriving in California and [it] became a rendezvous for the New Mexican caravans” who “waited for permission to enter or leave California.” Once approved for trading in California, Espinosa’s visitors left and then returned approximately six months later with herds of horses and mules to take back to New Mexico.[11]

Problems at Lugo’s started when his son established a rodeo near Politana, diverting water from irrigation ditches to sustain his stock and subsequently destroying crops downstream. Hipólito Espinosa, Lorenzo Trujillo, and several of the genízaro families decided to move, subsequently founding the communities of Agua Mansa and La Placita de los Trujillos to the southeast on land owned by Juan Bandini.[12] Together, the communities became known as San Salvador de Jurupa. Each settler received a tract of land that fronted the Santa Ana River and extended into the Jurupa Valley. There they built homes, raised livestock, planted crops, and kept watch for surprise attacks by thieves and marauders. The twin settlements eventually became productive agricultural communities. They established a school and a parish, even building a church and rectory for their first priest, who had been transferred from Mission San Fernando. Residents successfully defended their communities in 1846 during the Battle of Chino during the Mexican-American War, and—despite the influx of Euro-American social, political, and legal institutions after the United States’ victory—the citizens of San Salvador de Jurupa carried on as before.[13]

In 1851, Mormon emigrants began arriving in the San Bernardino Valley. Until their first harvest, the Latter-day Saints purchased their supplies in Agua Mansa.[14] A tremendous flood destroyed the community of Agua Mansa in 1862, and though the colonists rebuilt on higher ground at a place that became known as “Spanishtown,” they failed to regain their former prosperity. Most eventually moved to the South Colton area, and the church in Agua Mansa was shuttered. Their descendants, many of whom still live in present-day Colton, take pride in the fact that their ancestors founded one of the first New Mexican communities in Alta California, and their church was the first non-mission parish in Alta California. The remains of the Agua Mansa cemetery are the only significant above-ground remnants of the former village.15

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails- National Park Service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children. Thank you to the Old Spanish Trail Association for providing review of draft essays.

[2] There are many accounts of Espinosa’s arrival in California, but few agree on the exact year. Brown Jr., John and James Boyd. History of San Bernardino and Riverside Counties, vol. I (Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1922; Leroy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen, Old Spanish Trail (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993); Donald E. Rowland, John Rowland and William Workman, Southern California Pioneers of 1841 (Spokane and Los Angeles: The Arthur H. Clark Company and the Historical Society of Southern California, 1999).

[3] “Expedition Chronology between New Mexico and California,” Mojave River Valley Museum, accessed 2 Feb 2017, http://digital-desert.com/old-spanish-trail/chronology.html.

[4] Hafen and Hafen, Old Spanish Trail, 178.

[5] Harold A. Whelan, “Eden in Jurupa Valley the Story of Agua Mansa,” Southern California Quarterly 55, no. 4 (1973), 416.

[6] In the Old World, “janissaries,” from which genízaro derives, referred to Christian captives taken by Ottoman armies, faithful soldiers and defenders of the sultan. This was possible because they were taken as children – and performed exemplary military service. This coincides with the genízaro’s role as defenders of Spanish colonists’ property, creating a buffer zone to protect from raiding communities. Most recently scholars Enrique Lamadrid and Moisés Gonzáles have discussed the genízaro as a nation in their edited book, Nación Genízara: Ethnogenesis, Place, and Identity in New Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2019).

[7] R. Bruce Harley, “Agua Mansa: An Outpost of San Gabriel, 1842-1850,” California Missions Foundation, https://californiamissionsfoundation.org/articles/agua-mansa-an-outpost-of-san-gabriel/. This source says that Espinosa moved to Agua Mansa in 1840 and settled at Politana near the Martínez family and that Trujillo followed with the Rowland-Workman party the next year and also settled at Politana. Rancho San Bernardino was just one of several ranchos that the Lugo family owned in southern California.

[8] Joyce Carter Vickery, Defending Eden: New Mexican Pioneers in Southern California, 1830-1890, Occasional Monographs of the Department of History, University of California, Riverside (Riverside: Dept. of History, University of California, Riverside, 1977), 118–125.

[9] Harley, “Agua Mansa,” n.p.

[10] Vickery, 15.

[11] Whelan, 416.

[12] Ibid., 418.

[13] Ibid., 418–21.

[14] Ibid., 422.