Last updated: October 18, 2020

Article

Harry Garfield and the Spirit of Cooperation

Library of Congress

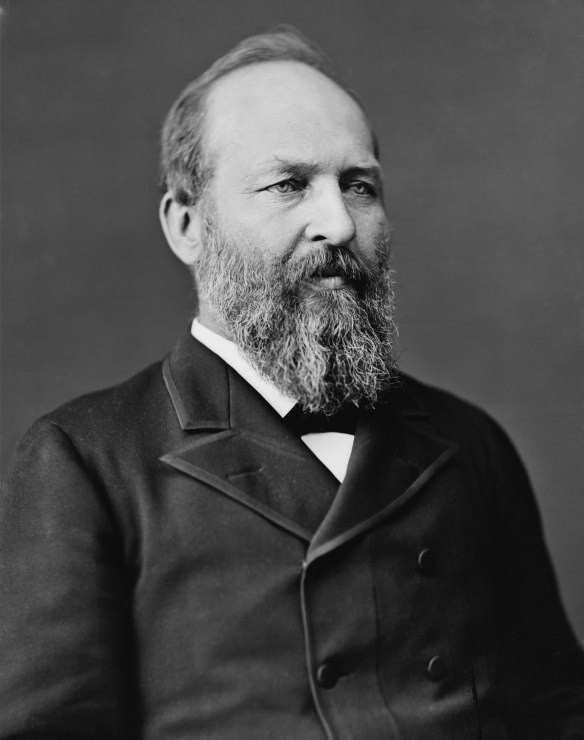

In reading and learning about James Garfield, I have wondered what his attitude toward the concerns of laborers would have been as clashes between labor and capital increased in the late nineteenth century. Looking through his published diaries, one can only speculate about how his views about the relationship between labor and capital might have evolved. This article will attempt to look broadly at the interplay of business, labor, and social order, and how James Garfield and his son Harry responded to those concerns.

Certainly, James Garfield was aware of “labor” as a political cause. In 1873, he noted having “made a call on [former North Carolina Republican] Senator [John] Pool, who is organizing a national workingmen’s association…I think it means a new party, based on the labor question.” With the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery there was talk in some quarters of the Republican Party that its purpose had come to an end. Garfield believed that economic issues were coming to the fore, and his comment above affirms that understanding.

Harpers Weekly

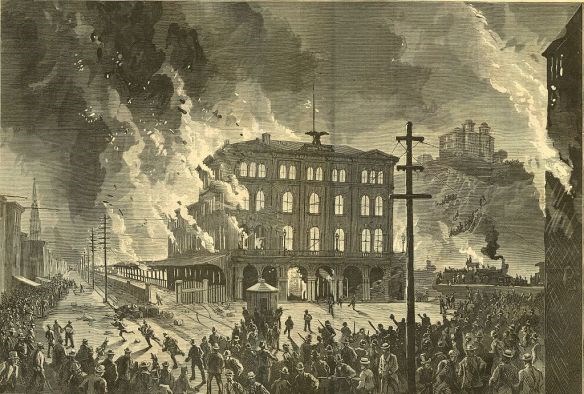

In one more observation that may have echoes in today’s political debates, Garfield wrote, “Isn’t the strike the legitimate offspring of the paternal theory of government? If we raise up a generation of men to believe that the object of protection [a high tariff to protect American industries and jobs] is to give laborers better wages, don’t they feel when times are hard that they have a right to take good wages by force? Studentum est. [It must be studied.]”

Williams College

n the later 1880s and 1890s, would James Garfield have supported rights of capital and the use of military force against striking workers, or would he have favored the laboring masses, among whom he found himself in earlier chapters of his life? Would he have remained steadfast to an unregulated form of laissez faire capitalism, or would he have agreed to regulation of the market? Or was there some other model for solving the capital-labor issues of his day?

President Garfield did not live to witness the increasing economic tensions of the last quarter of the nineteenth century – but his sons did. Might there be any clues about how he saw the economics of the new industrial age in the careers of his sons? Such an approach is tenuous, certainly, but it might shed some “reflected” light.

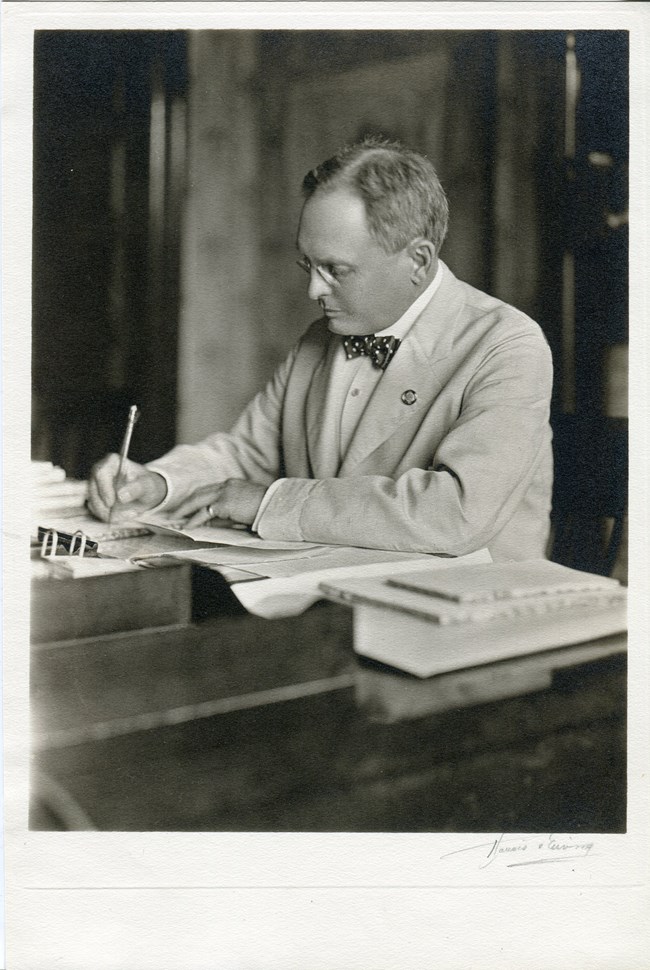

Unlike his father, Harry Garfield was not a diligent student in his younger years. However, in time, he did improve, and like his father and brothers, he attended Williams College, in Massachusetts (in time becoming its president). He was involved in student government, football, and baseball. After Williams, he became a successful Cleveland lawyer, practicing jointly with his brother James R. for several years.

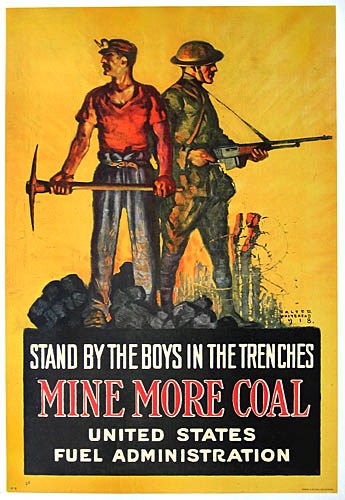

In 1903, Princeton president Woodrow Wilson invited Harry Garfield to join the faculty, to teach government and political science. Garfield was completely taken with Wilson’s personality and his plans for Princeton. According to Professor Robert Cuff, Garfield was so impressed with Wilson that he left the Republican Party for the Democrats. When Wilson, as president, took the United States into the Great War, he asked Harry Garfield to lead the Federal Fuel Administration, which was tasked with insuring a steady supply of coal for military and civilian needs, and with conserving the use of oil.

Library of Congress

According to Cuff, Wilson and Garfield shared a commitment to liberal academic culture and to the belief in an organic, evolutionary process of social change. They both believed that “cultivated” men should promote the cause of civilization. They did not believe that social progress would be achieved by “starting over from scratch.” Harry Garfield’s way was to “remodel, renovate, improve rather than start with a new plan…”

And, like many of his contemporaries, Garfield subscribed to the Progressive idea of “efficiency.” He was greatly influenced by Charles Steinmetz’s “America and the New Epoch,” in which the author argued that solutions to modern problems could be found not in the Federal government, but in the efficiency, competence, and responsibility of corporate administration. Cooperation, not competition, would create a better world. “We… have come to a time when the old individualistic principle of competition must be set aside and we must boldly embark upon the new principle of cooperation and combination.”

When Garfield came to Washington in August 1917, to head the newly formed Fuel Administration, he had to deal with both the owners of coal mines and the United Mine Workers. He meant to deal justly with the owners and the workers. A case in point concerns the price of coal set by the federal government in the wake of the war.

Wikipedia

There were controversies, to be sure. Railroads used the availability of cars to force bidding wars among rival coal companies for the lowest transportation price. Garfield ordered periodic work stoppages to prevent supply from outstripping demand, and in 1918, he resisted a wage hike for miners. He ordered conservation measures that angered parts of the general public He caught a lot of heat for such measures.

What Garfield was aiming at was cooperative administration between government, industry, and labor that would serve society not only in times of war, but also in times of peace. In this effort, he was praised by the Coal Trade Journal, for a “steadfastness of purpose… that is reminiscent of his father’s resolute spirit.” For Harry Garfield, it was the community interest, not the interest group, whose needs mattered most.

Perhaps the old saying, “like father, like son,” applies. In a “time of peace,” James Garfield saw the injustices that the owners of railroad committed, but believed that strikes, and the violence that attended them, were not a solution to the disputes of the day. During the emergency of war in 1917-1918, Harry Garfield attempted to satisfy the concerns of capital, labor, and the general public by encouraging cooperation with the goal of maintaining social order.

The competition of “interests” in James Garfield’s America, and the need to seek justice and maintain order was no less a phenomenon in Harry Garfield’s America forty years later – and nearly a century since Harry Garfield’s work as Fuel Administrator, what has changed?

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, July 2014 for the Garfield Observer.