Last updated: June 13, 2023

Article

Hampton National Historic Site: 75 Years of Preservation and Progress

National Gallery of Art

As World War II still raged in the spring of 1944, David E. Finley, Director of the recently opened National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC, was looking to enhance the museum’s newly established collection of American paintings. NGA Assistant Director Macgill James, a Maryland native and former director of Baltimore’s Peale Museum, learned of a great Thomas Sully portrait of Eliza Ridgely (“Lady with a Harp”) located in a private residence in Baltimore County. This was Hampton, a large Georgian mansion completed 1790 and home to seven generations of the Ridgely family. James and Finley soon visited Hampton to see the magnificent painting and discuss its possible acquisition by the museum.

This visit initiated a chain of events that eventually led to both the establishment of Hampton National Historic Site as a unit of the National Park Service in June 1948 and the subsequent founding of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. As the only National Historic Site established for its “outstanding merit as an architectural monument” rather than association with a famous person or singular historical event, Hampton became an important symbol for the historic preservation movement nationwide.

Photos of Hampton from the 1940s show the declining state of the house and property. During David Finley’s visit, Hampton’s owner John Ridgely, Jr. expressed his concern for the preservation of the late 18th century mansion and its collections. As early as August 1944, Finley was already advising Ridgely on potential ways to achieve this goal. The NGA’s collections were returned from wartime storage in Asheville, NC in fall 1944, and Finley worked assiduously to secure the Sully painting for the museum. Maude Monell Vetlesen, a prominent philanthropist funded the purchase, and in the summer of 1945, “Lady with a Harp” was taken down from Hampton’s Great Hall where the painting had hung for 116 years and transported to the NGA in Washington, DC.

NPS

Meanwhile, pursuing his hope that Hampton be preserved for future generations, NGA Director Finley worked to interest the National Park Service in the estate’s preservation. He also secured the financial support of Ailsa Mellon Bruce, daughter of NGA founder Andrew Mellon, and her philanthropic Avalon Foundation. The purchase of Hampton was typed “on a very old typewriter...in Mr. Ridgely’s bedroom…and a few minutes later it was signed.” (This typewriter survives today in Hampton NHS’ collection.) In April 1947, the Avalon Foundation made a grant of $90,000 to purchase the mansion, some of its contents, and 43 surrounding acres of land, including funds for repairs and restoration.

Due to Postwar-related budget constraints, the acquisition of Hampton by the NPS had to first meet the approval of the federal Bureau of the Budget. Further, a private partner organization was needed to serve as custodian. Having received payment in December 1947, the following month John Ridgely, Jr. hosted NPS Director Drury, NPS Chief Historian Ronald Lee, and another key figure in Hampton’s preservation, Robert Garrett, President of the Society for the Preservation of Maryland Antiquities, the local private organization that would be responsible for operating the site for the next 30 years. Soon thereafter, the deed for the property was signed.

NPS

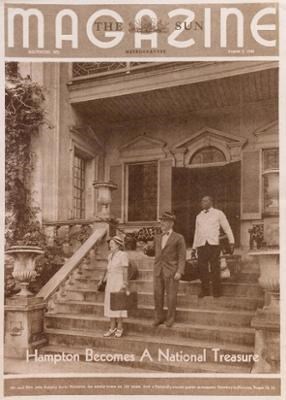

Following Congressional approval, Hampton was officially designated a National Historic Site 75 years ago on June 22, 1948. When Jane and John Ridgely, Jr. departed the ancestral home by early August, the Baltimore Sun Magazine cover extolled Hampton as a “National Treasure.” Following nearly two years of restoration work to the mansion and grounds, the formal dedication of Hampton NHS occurred on April 30, 1950. At this event, attended by dignitaries such as NPS Director Newton B. Drury and Maryland Governor William Preston Lane, SPMA President Garrett acknowledged Finley as “the real instigator of the Hampton project” and further noted “The preservation of Hampton is closely allied with, and indeed, is partly responsible for another important event…the organization of the National Trust for Historic Preservation...” which occurred that same year.

Hampton National Historic Site today interprets a much broader story than just the architectural importance of the mansion. In previous decades, Hampton’s interpretation, like that of many historic homes, focused primarily on the stories of the family who once lived there. In recent years, however, the park has shared the stories of all those, free and enslaved, who lived and worked at Hampton and explored how national social and economic events are reflected in Hampton’s history. In 2020, Hampton presented findings from an extensive ethnographic study that provided a wealth of information about Hampton’s enslaved individuals, families, and the communities that developed through the work of freedom seekers and formerly enslaved men and women. Tracing Lives in Slavery—Reclaiming Families in Freedom has enabled Hampton to share the stories of men, women, and children whose names and lives had been largely overlooked by historians for decades. Today’s story of Hampton continues to explore the idea of historic preservation but the site’s significance and value as national historic site is more far-reaching than Finley or his colleagues could have envisioned in the 1940s. Hampton National Historic Site’s origins as a “national treasure” and exemplar of Georgian-influenced American architecture provide visitors with a story of preservation of material culture and art to be sure, but the park’s vast collection of objects, archival materials, and rich landscape paired with recent scholarship provide visitors with opportunities to explore the stories of men and women seeking to preserve their families and communities in slavery and freedom.

NPS