Last updated: October 4, 2024

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Always Ready: Women in the Coast Guard during World War II

The United States Coast Guard. 190530-G-G0000-3003.

Introduction:

During World War II, opportunities for women expanded, including in the military. The Coast Guard, like other branches, created a women’s reserve known as the SPARS (Semper Paratus-Always Ready) in 1942. Thousands of women from across the United States enlisted. They went through basic training and then were stationed on the home front to “free a man up to fight.” Spars faced challenges and discrimination, but also contributed to the war effort in many ways.

Learning about their stories is one way to think about the contributions and changing roles of women during World War II.

Note about language: The Women’s Auxiliary was known as SPARS. An individual servicewoman was a Spar.

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for high school learners but can be adapted for learners of all ages.

Time period: World War II

Topics: World War II, women’s history, military history

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

This lesson relates to the following National Standards for History from the UCLA National Center for History in the Schools:

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Standard 3C: The student understands the effects of World War II at home.

- Grades 7-12: Analyze the effects of World War II on gender roles and the American family.

- Grades 7-12: Explore how the war fostered cultural exchange and interaction while promoting nationalism and American identity.

Historical Thinking Standard 2: Historical Comprehension

- Reconstruct the literal meaning of a historical passage by identifying who was involved, what happened, where it happened, what events led to these developments, and what consequences or outcomes followed.

- Appreciate historical perspectives–the ability (a) describing the past on its own terms, through the eyes and experiences of those who were there, as revealed through their literature, diaries, letters, debates, arts, artifacts, and the like; (b) considering the historical context in which the event unfolded–the values, outlook, options, and contingencies of that time and place; and (c) avoiding “present-mindedness,” judging the past solely in terms of present-day norms and values.

Historical Thinking Standard 3:

- Compare and contrast differing sets of ideas, values, personalities, behaviors, and institutions by identifying likenesses and differences.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

This lesson relates to the following Curriculum Standards themes for Social Studies from the National Council for the Social Studies:

Theme 2: Time, Continuity, and Change

Theme 5: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

Theme 8: Science, Technology, and Society

Theme 9: Global Connections

Relevant Common Core Standards

These lessons relates to the following Common Core English and Language Arts Standards for History and Social Studies for middle and high school students:

Key Ideas and Details

- CCSS ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

Craft and Structure

- CSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.6: Compare the point of view of two or more authors for how they treat the same or similar topics, including which details they include and emphasize in their respective accounts.

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.8: Distinguish among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH9-10.9: Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources.

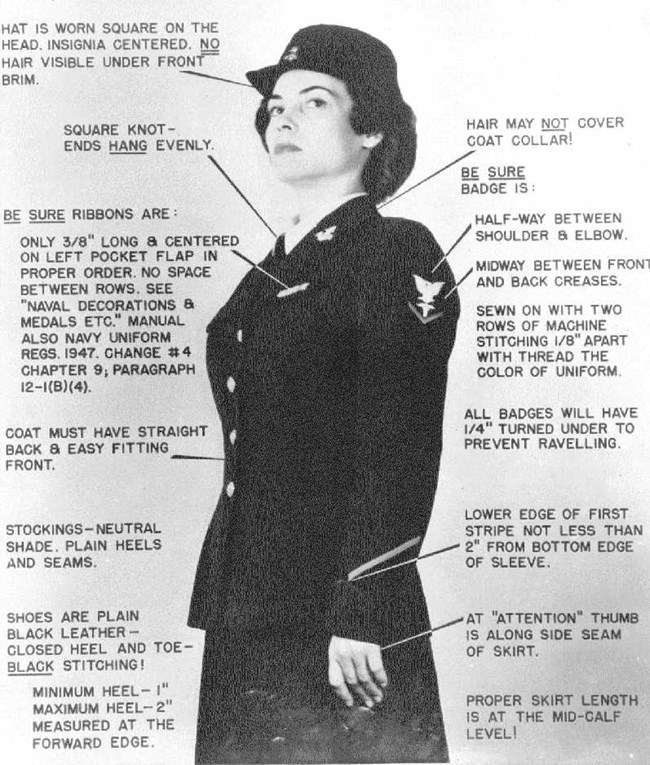

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard

Objectives:

-

Identify the roles women played in the Coast Guard and in the larger WWII effort

-

Identify challenges and opportunities faced by women in SPARS during WWII

-

Evaluate how women’s participation in WWII changed their roles during the War

Inquiry Question:

How did Spars’ experiences change the way they saw themselves during and after World War II?

Background Reading

The following article can be read by teachers for background knowledge or can be assigned to students.

Teacher Tip: Students could read and answer the questions for consideration. The questions can also be used to help guide students when taking class notes.

Questions for Consideration

-

Why were the SPARS established? How did it allow women to participate in the war effort?

-

What were the requirements for a woman who wanted to join the SPARS?

-

How were the women’s experiences in the SPARS, both during training and during their deployment, similar and different from a man in the Coast Guard? *This question may need you to form a hypothesis but be sure to back it up with evidence from the text!

Courtesy of the United States Coast Guard.

Student Activities:

Activity 1: Life in SPARS

Life in any military branch is often different than what people envision. SPARS, had to recruit women into the service. They had to do so quickly and in competition with other branches, like WACS or WAVES. All women serving in SPARS had to go through basic training. They were then assigned to a variety of jobs across the country. Some of these jobs used skills they already had, like typing or dictation. Others offered the opportunity to learn a whole new set of skills. Some women enjoyed the experiences in SPARS, others struggled with the new tasks or the attitude of those around them.

To learn more about why women joined SPARS and how their lives changed as a result, read about their experience once they had joined the Coast Guard. How did the experience meet expectations? How did their experiences over the course of war change their view of themselves and the United States?

The following are excerpts from Spars, collected either in writing or through oral history interviews. The excerpts are in order from shortest to longest. They also go in chronological order from training to deployment experiences. Choose 1 or 2 perspectives. As you read them, write down 3-5 phrases that describe their actual experiences. Consider:

- What did the women do?

- How difficult or easy were the tasks for them? How similar or different were they from what they experienced at home?

- How were they treated? Did they face any discrimination because they were women in the military? How did they respond?

Teacher Tip: Assign students different perspectives so they can come together and compare different readings. This step takes longer than the poster analysis, so this strategy can also save class time.

You can find more readings in the full group memoir, Three Years Behind the Mast.

SPARS Memoirs and Interview

Source:

Interview of Lillian Vasilas, USCGR by Scott T, Price, Deputy Coast Gurd Historian in August 2007.

INTERVIEWER: Where did you end up going through recruit training? Do you remember?

VASILAS: West Palm Beach.

INTERVIEWER: West Palm Beach. Yeah. I'm always fascinated by the fact that the fellow that owned that hotel offered it up to the Coast Guard.

VASILAS: Oh, really?

INTERVIEWER: Yes. He wanted to rent out the whole hotel. I mean, better money for him that way, I guess. It's called the Biltmore. It just looks like it -

VASILAS: Yes, it is.

INTERVIEWER: -- would be a nice place to go through basic training or boot camp. If you have to go through boot camp, I could think of worse places.

VASILAS: It wasn't bad. I understand they tore down some walls and things, and we had -- there was three bunk beds in the room I was in. So there was six of us in there, but being a first-class hotel, there was a bathroom for the six of us and shower. And boot camp wasn't difficult. There were guys running through, inspecting how you made the bed and all, and --

INTERVIEWER: Oh?

VASILAS: -- I think they liked to appear macho. But we would march down to the water, and we had to prove whether we could swim or not, and we did that in a pool -- in a swimming pool. And if we could swim good enough, then they'd let us go in the ocean.

Margaret Gorley Foley, Yeoman 1st Class on her training in Stillwater, Oklahoma. Behind the Mast, pg 23.

“We fell into routine easily, working hard trying to finish each day’s homework and keep our rooms shipshape as well. Captain’s inspection on Saturday was a white-glove inspection and the winds that blew in Oklahoma red dust certainly didn’t help any.”

“After breakfast at 5:30 we mustered outside, rain or shine. Most of the time the sun was rising over the hills throwing out fingers of bright hues. Each minute it would change, and each morning was different. With those magnificent Oklahoma sunrises before us it was a thrill to stand at attention. After ‘all present and accounted for’ we marched to classes to the beat of a drum. This always impressed me very much, for we followed three other companies of two platoons each, and all the way up the line ahead for blocks the girls’ white caps swayed the same way with their white gloves forming arcs at exactly the same time. The Radio City Rockettes have nothing over the girls who went to Oklahoma. And this feat wasn’t so simple, because the Air Force and Radar Men would stand about yelling, ‘Eyes right,’ or “you’re out of step sister, ‘ or ‘Hey, Cutie, your slip’s showing.”

Interview of Lillian Vasilas, USCGR by Scott T, Price, Deputy Coast Gurd Historian in August 2007.

Want to learn more about women and coding during World War II- explore “The Code Girls of Arlington Station.”

VASILAS: Well, I wanted to do the Morse Code and take messages from all over the world.

INTERVIEWER: Sure.

VASILAS: And the teletype was -- the radiomen here at Washington Radio Station in Alexandria, we teletyped the message to headquarters, and they did with it whatever. Actually, they needed radiomen down there. So they sent the three of us down there that had graduated from school.

INTERVIEWER: To Alexandria?

VASILAS: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: Okay.

VASILAS: The Washington Radio Station, the headquarters for Coast Guard radio. It’s still there, but they don't do that any more -- Morse Code is obsolete.

INTERVIEWER: Right.

VASILAS: I liked that, but all the messages were coded anyhow.

INTERVIEWER: So you didn’t know what the messages you sent to headquarters were? Do you remember what level the code was for these messages? Was it usually Top Secret or just Secret or all kinds?

VASILAS: I don't think that was on ours because it was coded, and it wasn't anything to read anyhow. It got sent to headquarters by teletype and to decoding.

INTERVIEWER: So you all were stationed down in Alexandria?

VASILAS: Yes, on Telegraph Road.

INTERVIEWER: On Telegraph Road.

VASILAS: Yeah, big station out there. It's still there. [TISCOM]

INTERVIEWER: They're still there. Where did you live?

VASILAS: Right there.

INTERVIEWER: On the station itself?

VASILAS: Yes. Upstairs and we worked in the radio shack downstairs.

INTERVIEWER: What was the division amongst men and women there? How many men, how many women were --

VASILAS: Well, there was only three women operators, and there were probably three or four yeomen up in the old man's office.

INTERVIEWER: Okay. And then how many men were there?

VASILAS: Oh, there were a lot. I don't know how many men.

INTERVIEWER: It was a big station.

VASILAS: There was -- the chief operator of the watch I was on was a man, of course, and I think there were two -- the three girls and two men operating --

INTERVIEWER: Okay.

VASILAS: -- in a room.

INTERVIEWER: Would you go over a typical day for us?

VASILAS: Well, we stood watch at different hours, usually about four hours a watch. You got to break to get some coffee. We made our own coffee and stuff there, but --

INTERVIEWER: So it was four on and then eight off, and then you'd go --

VASILAS: Yeah, and then you're --

INTERVIEWER: -- for another four hours?

VASILAS: -- back on, again, different shifts. One of the best things about it, other than the fact that I liked it, was we'd go on at midnight, and they'd give us dinner. Oh, there would be five of us, and the chef, so to speak, or the cook, enjoyed cooking for five. He could be more creative than cooking for the whole --

INTERVIEWER: The whole crowd.

VASILAS: And we got great meals.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, really. Well, I was going to ask you about the chow. So there's one question out of the way!

…

INTERVIEWER: What was your most memorable experience, you think, in the Coast Guard?

VASILAS: There or altogether?

INTERVIEWER: Well, while you were in uniform, or do you have one?

VASILAS: I don't think -- I enjoyed it all. I don't think there was anything any more memorable.

INTERVIEWER: Did you have a worse experience, one that you --

VASILAS: I had a couple of my -- only once. One of the questions is did I feel any resentment from men?

INTERVIEWER: Yeah. We're going to get to that whole issue in a little bit, but if you want to bring it up now, that's fine.

VASILAS: Okay. Well, at the Coast Guard Station, I was promoted to Second Class after a while and then took the tests and the stuff about antennas and everything and passed for First Class. The Chief did not like it, and I don't blame him. I did the job all right and I knew it, but that wasn't his argument. His thought was he had spent 20 years or so in the Coast Guard getting to be Chief.

…

VASILAS: I was very happy and very proud of the Coast Guard and felt I did a good thing. The day that I made First Class and the Chief was so upset -- he wasn't upset too much at First Class -- I made a big mistake in receiving stuff. We'll say it's the only one I made. You would copy these messages, and it was coded. It was all numbers, and you'd go over to the teletype and type it in, and then you'd take your paper that you had copied. You copied it onto a typewriter. We called it a "mill," and you'd hold it up along there and compare because one number off might change the whole mess.

This was after the war, though, and plain language was coming in, and that was interesting, getting messages from -- I'd call my mother, I'll be home, you know. I get this message from a guy in the China Sea someplace asking for, I think it was, $5,000 for a repair so he could come home, to repair his ship. I put the paper up there, teletype, electronic typewriter ran away with me and added two zeros.

INTERVIEWER: So you went to a half-a-million?

VASILAS: So the next day -- every morning, Mr. Dawson went through the messages that had come in, particularly the plain ones. Otherwise, they went up to the coding. But man the speaker down -- "What the hell is Spalding trying to do? Buy him a whole new ship?"

[Laughter.]

VASILAS: He checked it, and he fixed it and sent it out.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, okay.

VASILAS: And then was no --

INTERVIEWER: That's good.

VASILAS: -- repercussions, but somehow I remember that.

Harriet Writer (USCGR) was interviewed by C. Douglas Kroll in June 2012.

WRITER: It was wonderful. I think the men in the service maybe didn’t respect us totally, but they respected us enough to be nice to us.

INTERVIEWER: What was your life like at the Academy for SPAR officer’s training?

WRITER: They kept you busy all the time.

INTERVIEWER: Did you have any classes or training with male officer candidates or was it exclusively with SPAR officer candidates?

WRITER: It was just SPARs.

INTERVIEWER: What type of courses or training did you have while at SPAR Officer Candidate School at the Academy?

WRITER: All I remember are general officer training, sitting in classrooms.

INTERVIEWER: About how many SPAR officer candidates were in your class?

WRITER: I don’t remember exactly, somewhere between 50 and 100.

INTERVIEWER: Do you remember when you graduated from officers’ training and were commissioned?

WRITER: That must have been 1945 and then they sent me directly to Seattle. I lived with eight other SPAR officers on Mercer Island. When I went to work the first day the officer in charge said the commandant [District Coast Guard Officer] wanted a history of the Aleutian Islands. Honestly, I didn’t even know there were Aleutian Islands, I started researching and reading about them and I started making notes about them. Then my folks got sick and I asked for a transfer back to Boston to be near them.

INTERVIEWER: Did you ever finish the book? WRITER: No. I don’t if the next person finished it or not.

INTERVIEWER: It was your aunt and uncle that raised you that became sick that was the reason for your request to be sent back to the Boston area?

WRITER: Yes. When I got back to Boston they assigned me the Aids to Navigation again, but this time in the LORAN program. I was in charge of sending people to them and reading their daily reports. Every day they had to send in whether they were off operation and if so why, and for how long. That was such a big, top secret thing at the time and now it is absolutely nothing. Quite often the men didn’t want to be sent to Greenland, they wanted to be stationed right along the coast here in the United States.

INTERVIEWER: What was your typical day back in Boston as a SPAR officer?

WRITER: I would go to work and read all the reports from the LORAN stations or if someone got sick we would have to replace them and seamen would come in to be interviewed to see they were capable to going or had enough training for a LORAN station.

INTERVIEWER: What do you think was your most memorable experience in the Coast Guard?

WRITER: I enjoyed working in aids to navigation: a daily thing with the nuns and buoys, and the lighthouses --- all had to [be] shipshape for all the boats coming into Boston. There actually were some German submarines in the area that were never publicized, but it was true.

Class Discussion:

Share with your classmates, either in small groups or the whole class, what 3 things you learned about life in SPARS from your source(s).

Activity 2: Top Secret SPARS

Background Information: LORAN is a type of long-range navigation system. Electric signals are sent out from different radio stations to determine the relative position of a ship or plane. The technology was very new in World War II and could be sensitive. The Coast Guard operated 72 LORAN stations across the United States. By the end of World War II, these stations monitored 30% of the globe [1]. LORAN stations were operated in secrecy during the war.

Optional: Smithsonian Air and Space Museum Video on how LORAN works.

In 1944, a group of SPARS took over the LORAN monitoring station in Chatham, Massachusetts. Coast Guard historian Robin Thomson believes it was “the only all woman station of its kind in the world.” [2] The commanding officer, Lt. (JG) Vera Hamerschlag, wrote about her experience after the war in the SPARS group memoir, Three Years Behind the Mast.

“…Loran was so 'hush-hush' that not even the Training Officer had any conception of what the duties of these Spars would be, nor what their qualifications should be. The Engineering Officer had laconically said: 'Ability to keep their mouths shut.' Thus, all Spars selected were volunteers who had accepted the assignment with a spirit of adventure. It was the first time that Spars were being sent out of the district office. and the newness and mystery of the work was a challenge to us all.

“At the time I reported, Unit 21 was manned 100 percent by men and the idea was for them to leave for overseas assignments as quickly as we were capable of taking over. We did this within one month 100 percent Spars with the exception of one male radio technician who was a veritable 'man Friday' to us all. He acted as instructor as well, and left six months later when we felt qualified to accept the responsibility of technical maintenance…

“…Little had I realized when I was told I would be commanding officer of a Loran monitor station how many angles it involved. I was operations and engineering officer, medical officer, barracks officer, personnel officer, training officer-and even Captain of the Head! I had to learn the intricacies of plumbing, of a coal furnace, of a Kohler engine that supplied emergency power when the main line was out—and being on the CAPE there were nor’easters are frequent, the times were many. I remember the feeling I had when I looked at the 125’ mast for the station’s antenna and wondered which Spar would climb the riggin’ if something went wrong. I asked the CO [Commanding Officer] whom I was replacing who took care of it. His nonchalant answer was not to worry since nothing would happen to it short of a hurricane. Well, we had that too the following fall during which operations were suspended and all hands evacuated in case the mast should topple over on to the buildings!”

"The esprit de corps of Unit 21 was outstanding. We were a family unit. …The human element of the work kept it from getting dull and routine for the operators. The thought that we were participating in a system that was playing such an important part in winning the war gave us a feeling of being as close to the front lines as it was possible for Spars to be. Furthermore, we were part of a network that covered nearly all the world where we or our allies were fighting…”

Photo Courtesy of the US Coast Guard Historian's Office.

Reading Questions:

- According to Hammerschlag, why were Spars chosen to operate the LORAN Station in Chatham?

- How did Hammerschlag and the other Spars feel about taking over the LORAN Station?

- What jobs did the women expect to do? What jobs did they actually do?

- How did the SPARS at the Chatham LORAN station contribute to the US’ efforts in World War II?

Exit Ticket:

Teacher Tip: You can discuss this question as a class before leaving or ask students to write their own answers in a short paragraph, then submit it to you for assessment.

What part of women’s lives in the coast guard stood out the most to you? How were their lives different than many women at the time?

Teacher Tip: You may want to talk with students about gender roles in the 1930s and 1940s, and expectations of women’s lives before the War if you have not already done so. For more resources about how women’s lives changed during the war, see the Park Service Page on “Women in World War II.”

Call Out Box: Interested in more activities? See the companion lesson, (H)our History Lesson: “An Unforgettable Experience:” Diverse Stories of Women it the World War II Coastguard

Further Resources

“Why was LORAN such a Milestone?” from Time and Navigation: the untold story of getting form here to there. Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. https://timeandnavigation.si.edu/navigating-air/navigation-at-war/new-era-in-time-and-navigation/loran Accessed July 3, 2024.

Robin J. Thomson. “SPARS: The Coast Guard & the Women’s Reserve in World War II.” United States Coast Guard. https://www.history.uscg.mil/Browse-by-Topic/Notable-People/Women/SPARS/ Accessed June 25, 2024. The claim is also made in Three Years Behind the Mast (1946).

Lyne, Mary C. and Kay Arthur. Three Years Behind the Mast: The Story of the United States Coast Guard SPARS. Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Guard, 1946.

“Dr. Olivia Hooker: A SPAR’s Story.” U.S. Coast Guard. February 12, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q1CsWxQ7H18

“Olive J. Hooker, Pioneer and First Black Woman in the Coast Guard.” StoryCorps: February 28, 2020. https://storycorps.org/stories/olivia-j-hooker-pioneer-and-first-black-woman-in-the-coast-guard/

William H. Thiesen, “The Long Blue Line; Florence Finch—Asian American SPAR and FRC namesake dons uniform 75 years ago!” United States Coast Guard: February 7, 2022. https://www.history.uscg.mil/Research/THE-LONG-BLUE-LINE/Article/2925497/the-long-blue-line-florence-finchasian-american-spar-and-frc-namesake-dons-unif/

Vojvodich, Donna. “The Long Blue Line: ‘Sooner Squadron’—First Native American Women to Enlist in the Coast Guard.” United States Coast Guard. November 5, 2021. (The Long Blue Lione: Sooner Squadron.)

This lesson was written by Alison Russell, a consulting historian for the National Park Service in partnership with the National Council on Public History.