Last updated: August 22, 2025

Article

Coastal Dynamics Monitoring at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Mississippi and Florida: 2018-2024

NPS photo / GULN staff

Summary and Key Findings

In the spring of every other year, the Gulf Coast Network (GULN) conducts geomorphology monitoring at Gulf Islands National Seashore (GUIS) as a part of the NPS Vital Signs Monitoring Program.

Monitoring is conducted following methods detailed in the Protocol Implementation Plans for Coastal Topography (Bracewell 2017a) and Shoreline Position (Bracewell 2017b). This report presents results for the 2024 season and compares change over time. In 2024, a shoreline position survey was completed for the length of the Fort Pickens and Perdido Key gulf shores, as well as the entire coastal margins of Petit Bois, West Petit Bois, and Horn Islands. There was also a topography survey at 32 transects distributed across the aforementioned park areas.

Key findings from this effort are as follows:

- No named storms impacted the study area during the last two years. There were also fewer high wind and high-water level days recorded within this time span, compared to previous reporting periods in this series.

- Long-term shoreline retreat and losses in Profile Area were greater in Mississippi than in Florida, as was the case in the previous GULN geomorphology reporting period (2018 to 2022).

- Restoration activities at Pensacola Pass have stabilized the footprint of Perdido Key, but its longer-term changes, since 2018, show overall retreat in shoreline and dune crest position.

- An area south of Battery Payne at Fort Pickens has a particularly high rate of shoreline retreat that coincides with findings from a recently published study for Escambia County (Olsen 2023).

Introduction

Coastal barrier islands are dynamic physical foundations for ecosystems. Winds, tides, and currents constantly shape and reshape island landforms, as do extreme weather events, sea-level change, and human activities. In coastal regions where change is a constant, resource management and protection require an understanding of geomorphic change rates, severities, and potential causes. To address this need, the Gulf Coast I&M Network (GULN) conducts coastal geomorphology monitoring at two National Seashores, based on methods established by the Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network (Psuty et al. 2010, 2012). The Gulf Coast Network records coastal topography –i.e., the beach/dune elevation profile, and shoreline position using the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) during surveys conducted in the spring of alternate years (Bracewell 2017a, 2017b). This document reports the network's most recently collected geomorphology data for Gulf Islands National Seashore, within the context of the long-term shoreline position and topographic change datasets for the park. Data and findings from previous surveys are available at the Gulf Coast Network Shoreline and Coastal Topography Monitoring Projects on the Integrated Resource Management Applications (IRMA) Portal.

Study Area

Gulf Islands National Seashore includes districts in both Florida and Mississippi. The Mississippi District (GUIS-MS) consists of five islands and their surrounding waters. These islands are Cat, Ship, Horn, West Petit Bois, and Petit Bois Islands, in order from east to west. There is also a small mainland headquarters area in Mississippi. The Florida section (GUIS-FL) consists of two small mainland areas and portions of two islands: Perdido Key and Santa Rosa Island, which includes Fort Pickens. The GULN coastal geomorphology monitoring effort focuses on Horn, Petit Bois, and West Petit Bois Islands in the Mississippi District and Fort Pickens and Perdido Key in the Florida District (Figure 1).

Florida transects are spaced 1 km apart, Petit Bois transects are 2 km apart, and Horn Island transects are 4 km apart.

There are many aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems in Gulf Islands National Seashore, including Gulf, bay, dunes, salt marsh, maritime forest, barrier islands, seagrass beds, and other marine systems. The plant and animal communities in the park exist in a highly dynamic environment, with landforms changing regularly and to varying degrees in response to high tide or wind events. Hurricanes, which combine both strong winds and high tides, are among the biggest agents of change in the park. They can rapidly reshape shorelines and adjacent landscapes through wind, flooding, erosion, and overwash of the islands. In doing so, they drastically impact biological communities as well as park structures and facilities.

Hydrology and water-related issues are of central importance to park management. This is not only because the park experiences frequent flooding and water-related damage, but also because 80% of the park is submerged land (Anderson et al. 2005). Hydrologic alterations (e.g., jetties and navigation channels) disrupt sediment input and transport, limiting the ability of these systems to recover on their own between storms. To combat erosion, the beaches of Gulf Islands National Seashore have been regularly nourished with sand, which generally comes from the dredging of navigation channels. Although these nourishment projects are beneficial for the reduction of erosion, there is concern regarding the rates of revegetation, adverse effects on macroinvertebrates, and reduction of the vegetative seed bank (Cooper et al. 2005).

Weather and Water Levels

Shoreline position and coastal topography are influenced by regular weather and tidal events, as well as by the more extreme conditions brought on by hurricanes or other storms. To track tidal conditions, the Gulf Coast Network uses water level records from the tide stations at Pensacola, FL, for Fort Pickens and Perdido Key, and at Pascagoula, MS, for Horn, Petit Bois, and West Petit Bois Islands. Weather stations at the Pensacola Naval Air Station and Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, MS, are used to track wind (station locations in Figure 1).Along with geomorphic changes related to storm strength and frequency, park managers must consider sea level rise in long-term management planning. Table 1 presents 2023 estimates of relative sea level trends assembled from NOAA (2023a) for three stations spanning the longitudinal extent of the park. In all cases, the values are positive, indicating that water levels are rising, the land surface is subsiding, or some combination of these variables is causing land to become increasingly inundated. Across the three stations, mean sea level rise estimates average 3.9 mm/year for the seashore.

Table 1. Relative sea level trends at three stations near GUIS from NOAA (2023b). Mean Sea Level (MSL) is presented as gain in mm/year with 95% confidence interval.

| Station ID | Station Name | Last Year | Year Range | MSL Trends (mm/yr.) |

| 8747437 | Bay Waveland, MS | 2023 | 45 | 4.7 (+/- 0.68) |

| 8735180 | Dauphin Island, AL | 2023 | 57 | 4.41 (+/- 0.55) |

| 8729840 | Pensacola, FL | 2023 | 100 | 2.69 (+/- 0.23) |

A record of high wind and high-water level events starting in 2017 is presented in Figure 2. Table 2 shows named storm events that coincide with those conditions. A noticeable peak in tropical storm activity occurred in 2020, followed by diminishing storm occurrences through the fall of 2021, then frequent, less intensive storms leading up to the spring 2024 surveys (NOAA 2023a, 2023b). Details about previous weather and high tide events dating back to 2017 are available in Bracewell (2023).

Figure 2. High wind and water level events reported near GUIS Florida and Mississippi districts from April 2017 to April 2024. The orange portion of a bar represents the count of days where winds were sustained at >=25 mph for 1+ hour, the blue represents water levels >= 0.7 meters NAVD88, and the grey represents events where those two conditions temporally overlap. The period of record for each bar is the two years leading up to the start of the GULN’s survey window on April 1.

Table 2. Named tropical systems that coincided with high wind and water conditions at the Mississippi and Florida Districts of GUIS.

| District | Date | Max of verified water level (meters rel. to NAVD 88) | Daily Max of HourlyWind Speed (mph) | NamedStorm |

| MS, FL | 6/21/2017 (MS), 6/22/2017 (FL) | 0.96, 0.85 | 30, 26 | CINDY |

| FL | 8/30/2017 | 0.66 | 26 | HARVEY |

| MS, FL | 10/8/2017 | 2.16, 1.21 | 25, 32 | NATE |

| MS, FL | 9/4/2018 | 0.64, 0.94 | 25, 29 | GORDON |

| MS | 10/8/2018 | 0.93 | 31 | MICHAEL |

| MS | 10/26/2019 | 0.96 | 30 | OLGA |

| MS | 6/8/2020 | 1.16 | 33 | CRISTOBAL |

| MS, FL | 9/15/2020 | 1.28, 1.30 | 31, 74 | SALLY |

| FL | 9/23/2020 | 0.81 | 25 | BETA |

| MS | 10/10/2020 | 1.18 | 33 | DELTA |

| MS | 10/28/2020 | 2.39 | 64 | ZETA |

| MS | 6/19/2021 | 1.17 | 40 | CLAUDETTE |

| MS, FL | 8/29/2021 | 1.34. 1.00 | 40, 36 | IDA |

Human Impacts on Geomorphology

National seashore landforms are protected from most forms of human modification, but there are exceptions. For example, the park regularly undertakes projects to modify landforms in beneficial ways, such as beach building with dredge material and restoration fencing or planting. Since the spring of 2022, over one million cubic yards of sand have been placed on the eastern end of Perdido Key. This project and other dredging activities are reported in Table 3.Table 3. Summary of dredging events since 2016 at Pensacola Pass in Florida (FL) and Horn Island Pass in Mississippi (MS). A dash represents missing information.

| COE Project Code (Park District) |

Dredging Period |

Dredge amount (Cubic Yards) |

Disposal Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| - (FL) | 2016 (November) | 238,700 | Perdido Key - Nearshore |

| W9127817D0092 (FL) | 2018 (May 10–26) | 194,625 | Within channel placement |

| W9127819D0019 (FL) | 2020 (October - November) | 186,073 | Within channel placement |

| W9127821D0083 (FL) | 2022 (March–April) | 140,000 | Perdido Key - Beach placement |

| - (FL) | 2023/2024 | 915,666 | Perdido Key - Beach placement |

| W9127817F0243 (MS) | 2018 (January 2018 & May) | 116,031 | West Petit Bois |

| W9127818C0022 (MS) | 2019 (May–September) | 639,330 | Ship Island |

| W9127821F0004 (MS) | 2021 (March–April) | 159,233 | West Petit Bois |

| - (MS) | 2022 (October–December) | 516,036 | - |

| - (MS) | 2024 (April) | 170,832 | West of West Petit Bois |

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection published an inlet management plan for Pensacola Pass in 2024 that outlines sediment sources, disposal zones for beach nourishment, rates of replenishment to maintain a target island footprint, and a monitoring plan to evaluate changes over time (FDEP 2024).

Sampling Schedule and Field Methods

All GULN coastal geomorphology surveys, including the most recent event, follow the sampling schedule and methods as published in Bracewell (2017a, 2017b). To summarize, all fieldwork is scheduled to coincide with neap tide periods in April and May of every other year. Neap tides are the two periods per month when high and low tides are the least different. For a given survey season, these periods are determined based on predicted water levels using the closest NOAA monitoring stations at Pascagoula, MS, and Pensacola, FL (NOAA 2023b).To measure topography, groups of cross-shore virtual transects are projected along the seashore at areas of high park management interest. A crew member walks along each transect and records elevation, longitude, and latitude on precision GNSS equipment at topographic inflections in the beach and primary dune complex. These x, y, and z coordinates are plotted as profiles for documentation and comparison (Bracewell 2017a).

To record shoreline position, a crew member walks or drives the high tide swash line with a handheld or utility task vehicle (UTV)-mounted GNSS unit. A wet/dry border in the sand, shell hash, or other debris generally marks the swash line. Positional data are differentially corrected in real-time or during post-processing, and results are exported into a standard GIS format.

The coastal geomorphology fieldwork for 2024 was completed on April 16–19 in Florida, and April 30–May 3 in Mississippi. In Mississippi, shoreline surveyors used EOS Arrow Gold+ GNSS receivers, which reported an average horizontal accuracy of 0.17meters (standard deviation of 0.16 m). In Florida, a Trimble R12i was used for shoreline surveys and reported an average horizontal accuracy of 0.02 meters (standard deviation of 0.003 meters). Pre- and post-survey check-ins on geodetic control benchmarks yielded a range of vertical accuracies from 0.003 meters to 0.04 meters.

Shoreline Change Rate Calculations

To calculate shoreline position change in GUIS-FL, GULN uses the Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS; Himmelstross et al. 2024). This approach compares shoreline position over time at spatially fixed cross-shore transects distributed every 50 meters (164 feet). Changes in shoreline position are calculated using the Net Shoreline Movement (NSM) method and a combination of net movement and annual rate is presented. The NSM method simply calculates the distance between shoreline positions along cross-shore transects as they were recorded at different times. At GUIS-MS, the analytical approach is similar, except that island width is calculated due to large amounts of variation in shoreline position on both Gulf and Sound sides of these islands (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Panel (A) shows measurements for calculating change in shore width in the Mississippi District (Time 2 – Time 1). Panel (B) shows measurements for calculating shoreline displacement in the Florida District using DSAS (Time 2 – Time 1). Transect measurements originate from a spatially fixed baseline.

Shoreline change is averaged by park area in the figures and tables in the Results section. For a more continuous depiction of shoreline change, see supplemental materials (SM1). For the purposes of this report, the Gulf Coast Network focuses on change over two temporal scales: longer-term change (2018–2024) and recent change (2022–2024).

Topographic Measurements and Change Calculations

Dune topography profiles are structured to originate at a physical or virtual benchmark (0.0 meters horizontal), which is located behind the foredune complex, or, for narrow landforms, extend from shore to shore. Measurements are taken in the active part of the beach/dune system, and they do not always extend to the origin. To quantify dune features and measure change, four main metrics are calculated from the profile: Distance to Dune Crest (referring to the foredune crest), Dune Crest Elevation, Distance to 0.0 Meters NAVD 88, and Profile Area (see examples of each metric in Figure 4). Profile Area is the two-dimensional area under the profile measured to 0.0 meters NAVD 88. Of these four metrics, Distance to 0.0 Meters NAVD 88 is not covered in detail in the current report. This metric is useful for determining beach width and shoreline position but is redundant in the current report because of the co-presentation of a continuous shoreline position summary. To estimate change over time in dune topography, measurements from each topographic profile are compared across years. Negative numbers represent landward retreat or lower elevations. Change in Profile Area for each transect is calculated as ([final area - initial area] / initial area), and overall change across all transects in a unit is calculated as ([∑final area - ∑initial area] / ∑initial area). Graphical depictions of each profile in each year are provided in supplemental materials (SM2).

Figure 4. Example of key profile dimensions. Arrows indicate: Distance to Dune Crest, Dune Crest Elevation, and Distance to 0.0 Meters NAVD 88. The hatched portion under the 'Time 2' profile is the area calculated for Profile Area dimension. Each topographic measurement point is labeled with ‘Distance from Benchmark’ for each year. All elevation measurements are referenced to NAVD 88, Geoid 12B.

Results: Shoreline Change

Shoreline Change Mississippi

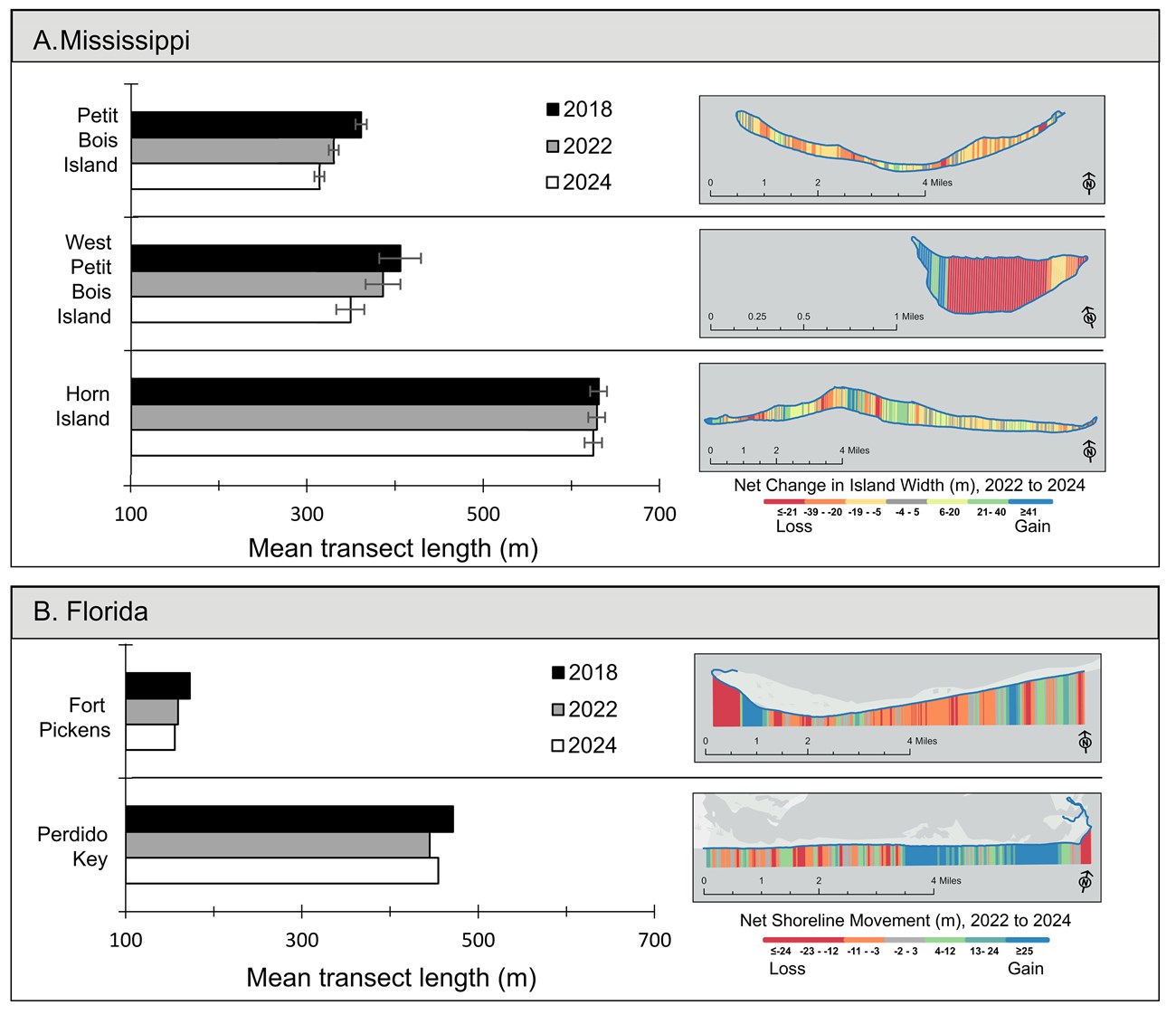

Over both the short- and long-term time periods, all islands in Mississippi exhibited overall shoreline retreat (Figure 5A). Rates of short- and long-term change were correspondingly negative, with the most dramatic change rate occurring at West Petit Bois Island, where the shoreline retreated an average of 18 meters (59.1 feet) per year from 2022 to 2024, compared with 9 meters (29.5 feet) per year from 2018 to 2024 (Table 4). Detailed maps of shoreline change between 2022 and 2024 are provided for each island in Supplemental Materials Document 1 (SM1).

Companion maps for each Area show short-term change, measured as net change in island width for MS and net shoreline movement for FL. Each shoreline transect is colored to demonstrate the gradient from loss (red) to gain (blue) between 2022 and 2024.

Table 4. Total change in shoreline transect length in meters over the short term (2022 to 2024) and over the long term (2018 to 2024) by island or area within the Mississippi (MS) and Florida (FL) Districts. Net change was calculated as transect length in the second year minus the transect length in the first year averaged within each park Area. The annual rate of change was the net change in transect length divided by number of years between surveys (2 years for the short term and 6 years for the long term).

| District | Island or area | Net short-term change | Net long-term change | Annual rate of change over the short term | Annual rate of change over the long term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | Petit Bois Island | -16.1 | -47.0 | -8.1 | -7.8 |

| MS | West Petit Bois Island | -36.5 | -56.0 | -18.3 | -9.3 |

| MS | Horn Island | -3.8 | -6.0 | -1.9 | -1.0 |

| FL | Fort Pickens | -3.6 | -17.3 | -1.8 | -2.9 |

| FL | Perdido Key | 9.7 | -17.1 | 4.8 | -2.9 |

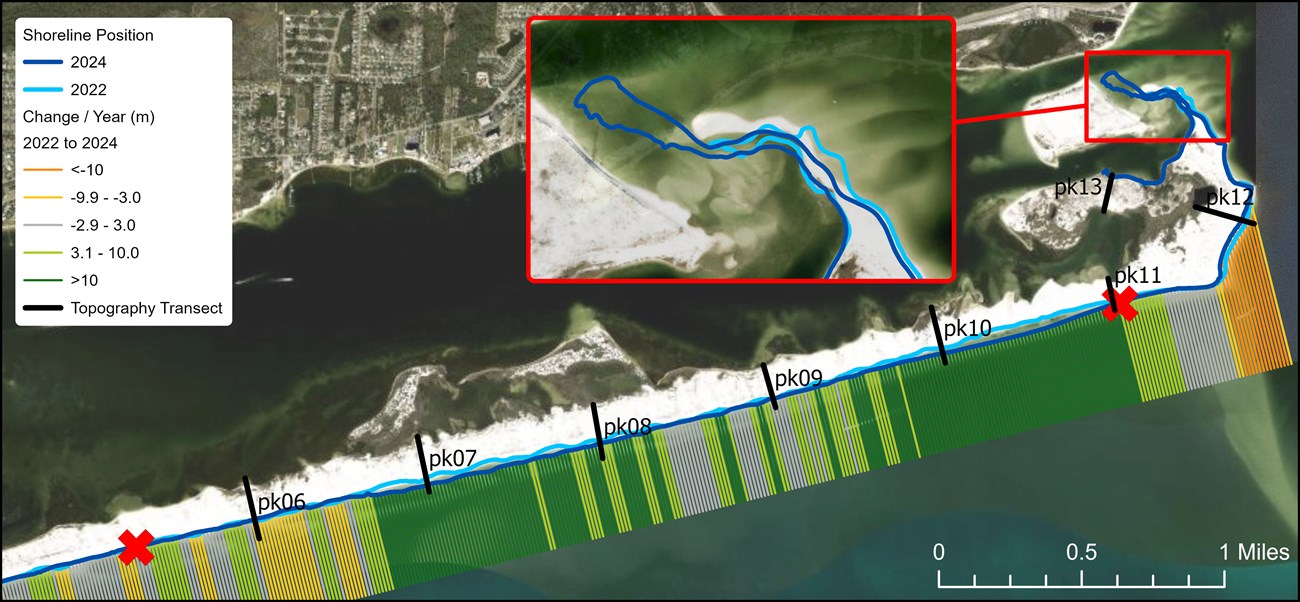

Shoreline Change Florida

Within the Florida District, Fort Pickens and Perdido Key differed in their patterns of shoreline change (Figure 5B, Table 4). Fort Pickens was similar to the Mississippi islands, in that it exhibited a net loss in both the short and long term. The only instance of shoreline advance during the current study was over the short term at Perdido Key, where the average displacement was almost 10 meters (32.8 feet), following extensive beach nourishment. However, long-term shoreline retreat at Perdido Key was about 17 meters (55.8 feet), similar to the average long-term retreat at Fort Pickens. See Supplemental Materials Document 1 (SM1) for detailed maps of shoreline change between 2022 and 2024 for the two monitoring areas in Florida.

Results: Topographic Change

Topographic Change Mississippi

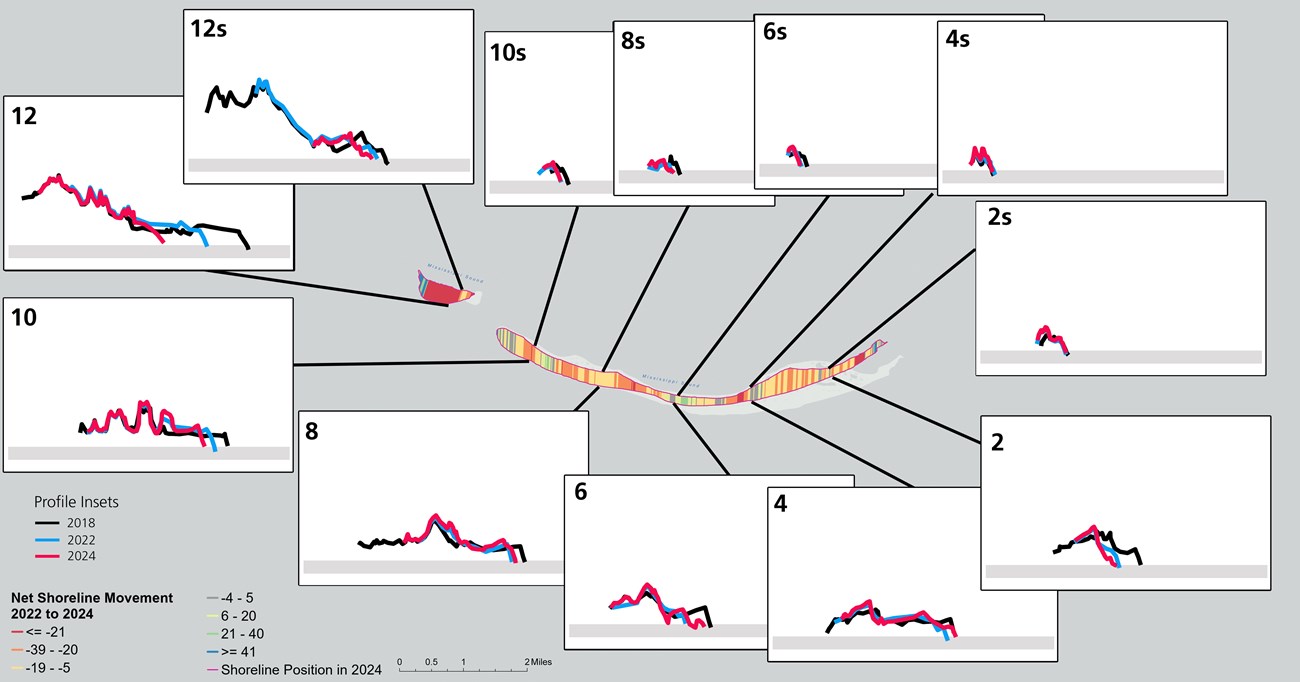

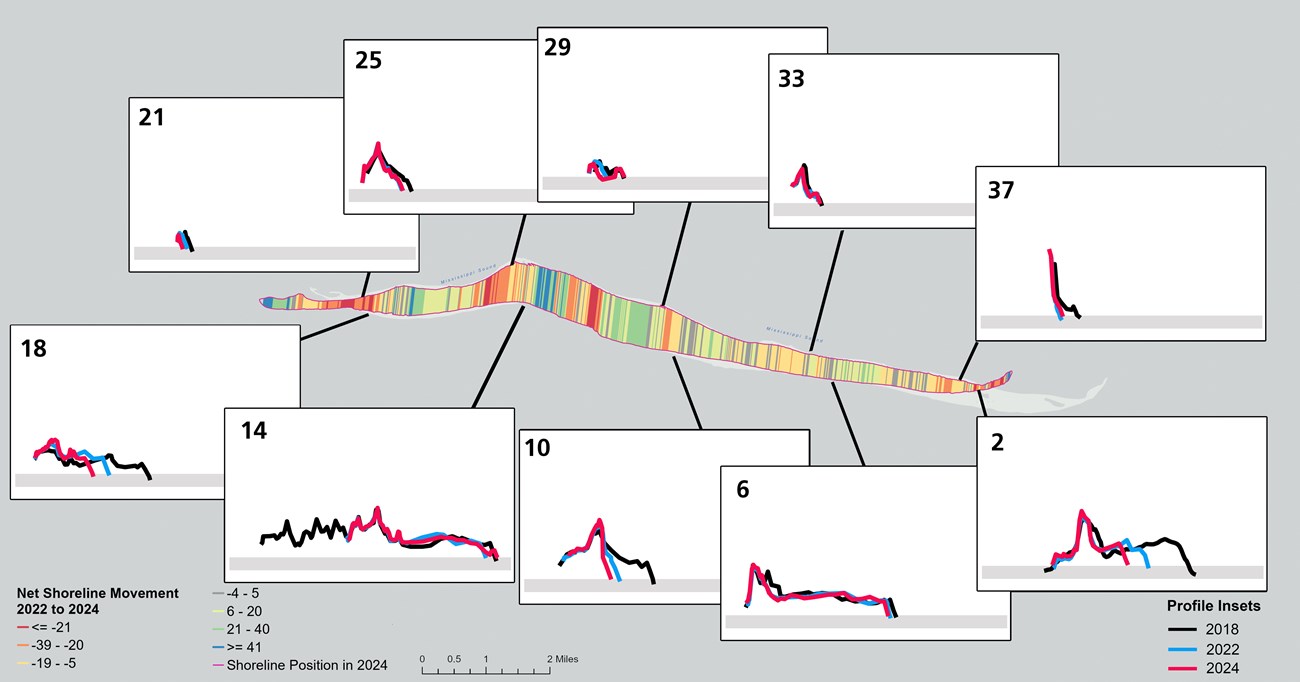

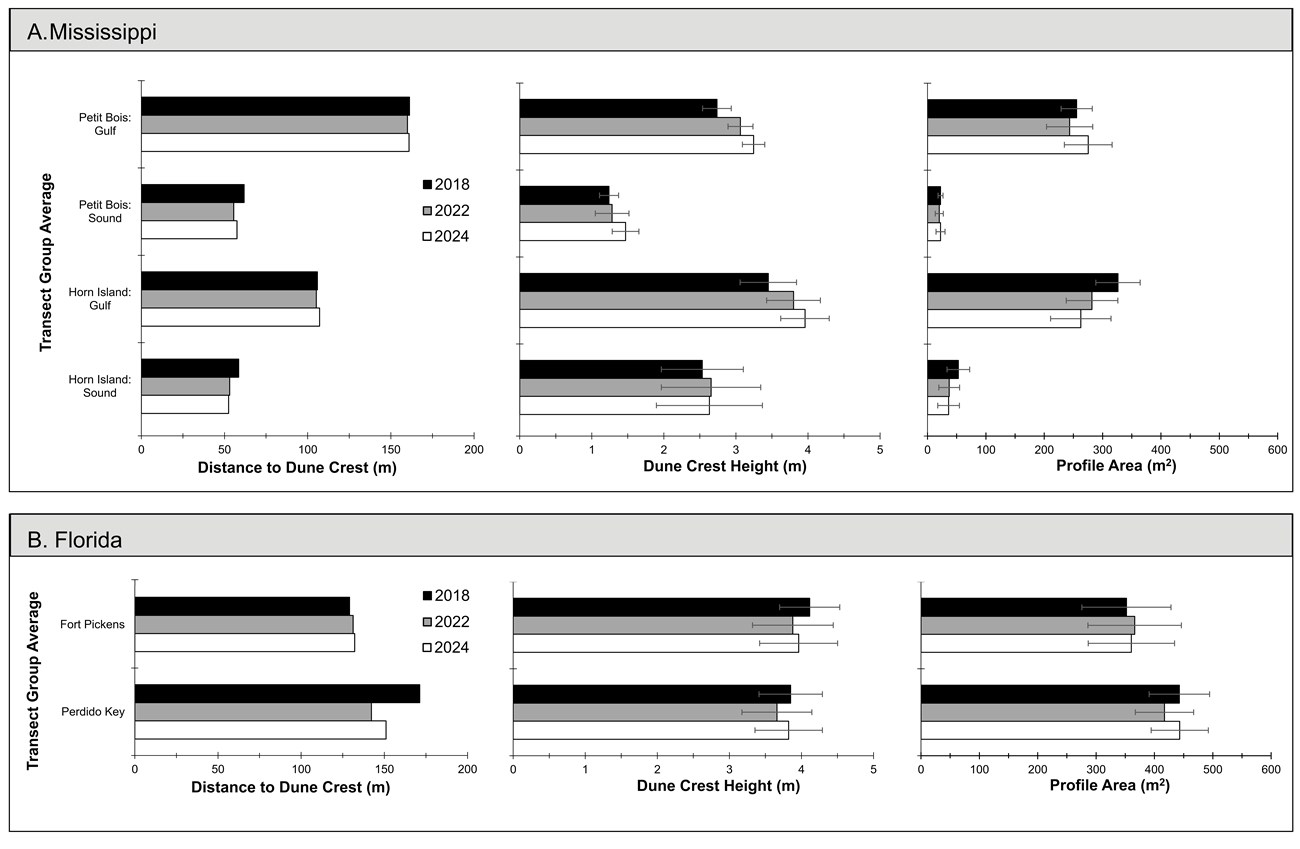

The Mississippi islands exhibited complex patterns of topographic change from 2018 to 2024, but in general, losses in topographic features were consistent with patterns of shoreline loss over the short term (Figures 6 and 7). Since the gulf side of a Mississippi barrier island is a higher-energy environment than its sound side, comparisons for topographic change considered gulf and sound transects separately. This was done for net change and rates of change (Table 5), as well as for average Dune Crest Position, average Dune Crest Height, and average Profile Area (Figure 8A). Patterns of change are discussed for each island side, or both sides together for West Petit Bois, in the sections below. Detailed plots of each topographic transect in 2018, 2022, and 2024 are included in Supplemental Materials Document 2 (SM2).

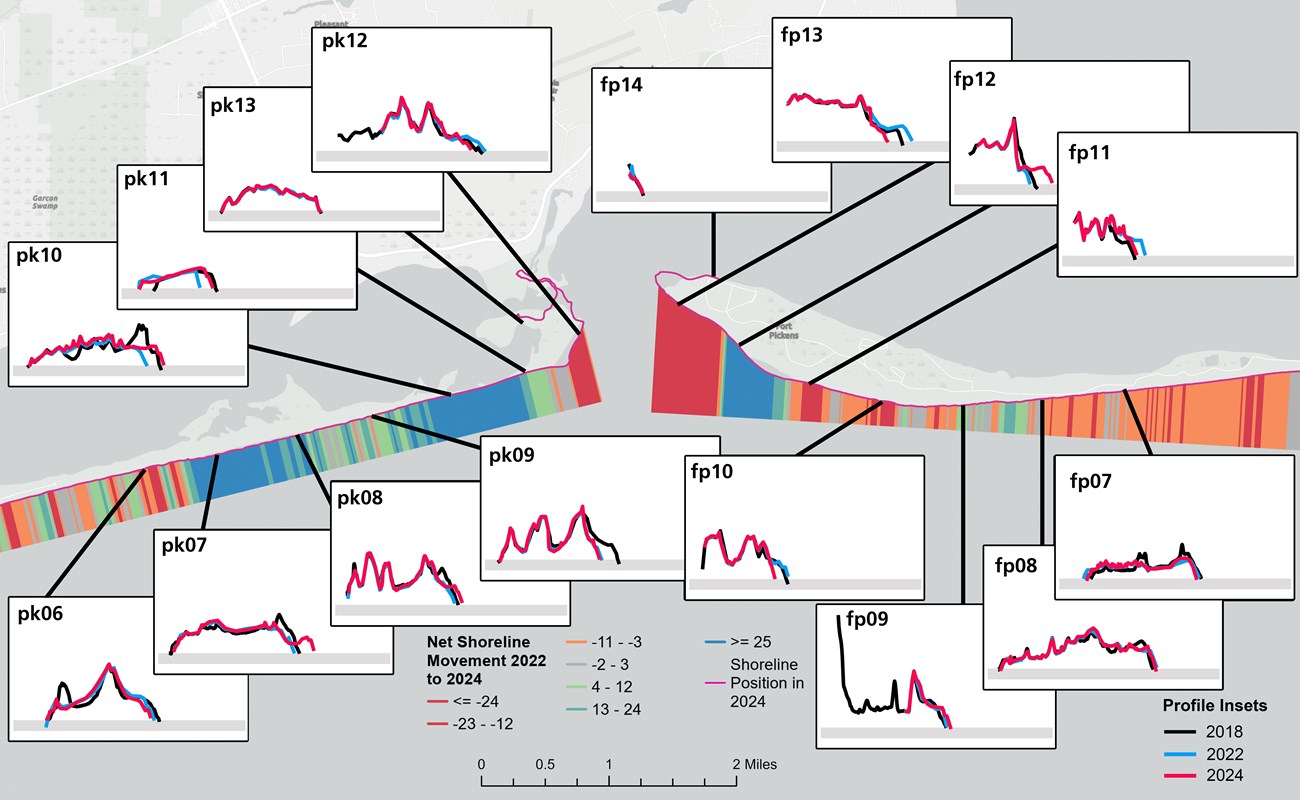

Different colored bands indicate different amounts of change, in meters. Shoreline change classes are the same in Figures 6 and 7, but they differ in Figure 9. All insets are presented at the same scale (grey bar 1 meter tall and 420 meters long).

Different colors in the bands represent different amounts of change, in meters. Shoreline change classes are the same in Figs. 6 and 7 but differ in Figure 9. All profile insets are presented at the same scale (grey bar 1 meter tall and 420 meters long).

Table 5. Changes in Distance to dune crest (meters), Dune crest height (meters), and Profile area (square meters) for both short-term (2022 to 2024) and long-term (2018 to 2024) comparisons in the Mississippi (MS) and Florida (FL) Districts. Standard error is presented within parentheses.

| District: transect group (count) |

Short-term change in distance to dune crest | Long-term change in distance to dune crest | Short-term change in dune crest height | Long-term change in dune crest height | Short-term change in profile area |

Long-term change in profile area |

| MS: Petit Bois Island Gulf (5) | 0.90 (+/- 1.4) | -0.30 (+/- 3.5) | 0.18 (+/- 0.03) | 0.51 (+/- 0.07) | 13% | 8% |

| MS: Petit Bois Island Sound (5) | 1.90 (+/- 0.9) | -4.30 (+/- 3.8) | 0.19 (+/- 0.06) | 0.23 (+/- 0.16) | 11% | -1% |

| MS: Petit Bois combined (10) | 1.41 (+/- 0.8) | -2.31 (+/- 2.0) | 0.37 (+/- 0.09) | 0.18 (+/- 0.03) | 4% | -2% |

| MS: Horn Island Gulf (5) |

1.90 (+/- 1.8) | 1.30 (+/- 2.6) | 0.16 (+/- 0.05) | 0.51 (+/- 0.18) | -7% | -20% |

| MS: Horn Island Sound (5) | -0.70 (+/- 0.4) | -6.10 (+/- 2) | -0.02 (+/- 0.06) | 0.10 (+/- 0.21) | -3% | -32% |

| MS: Horn Island combined (10) | 0.61 (+/- 1.0) | -2.41 (+/- 2.0) | 0.30 (+/- 0.15) | 0.07 (+/- 0.05) | -6% | -21% |

| MS: West Petit Bois Gulf (1) | 46.60 | -18.70 | 0.23 | -0.04 | -14% | -15% |

| MS: West Petit Bois Sound (1) | 0.10 | 0.30 | -0.12 | 0.02 | -23% | -25% |

| FL: Fort Pickens (8) | 0.90 (+/- 0.7) | 3.10 (+/- 1.3) | 0.08 (+/- 0.04) | -0.15 (+/- 0.22) | -2% | 2% |

| FL: Perdido Key (8) | 8.10 (+/- 6.7) | -20.30 (+/- 15.8) | 0.16 (+/- 0.05) | -0.03 (+/- 0.18) | 6% | 0% |

| FL: Florida combined (16) |

4.51 (+/- 3.6) | -8.61 (+/- 8.7) | -0.09 (+/- 0.14) | 0.12 (+/- 0.03) | 3% | 1% |

West Petit Bois Island is not included in this figure because it had only one cross-island transect; short- and long-term change for this transect is reported in Table 5.

Horn Island Gulf Side (Transects hi02 – hi18) change is characterized by long-term stability in Dune Crest Position (+1.3 meters) and Dune Crest Height (+0.5 meters), but there has been a 20% loss in average Profile Area. This loss commonly resulted from a retreat or loss of the beach berm; see hi10 for example (SM2).

Horn Island Sound Side (Transects hi21 – hi37) experienced a long-term retreat of Dune Crest Position (-6.1 m) while showing a more modest short-term retreat of just 0.7 meters. This pattern was echoed in Profile Area, where there was a long-term loss of 32% but only a 3% loss in the short term. On average, there was little variation in Dune Crest Height, with a loss of 0.1 meters long-term and 0.02 meters short-term.

Petit Bois Gulf Side exhibited little change in Dune Crest Position over both long- and short-term periods, with measurements of 0.9 meters and -0.3 meters, respectively. Likewise, Profile Area and Dune Crest Height measurements experienced positive changes in both long- and short-term periods (8% and 13%). The most noticeable change among the profile graphs is an average increase in Dune Crest Height of 0.51 meters in the long term.

Petit Bois Sound Side Profile Area averages decreased slightly in the long term (-1%) but gained 13% in the short-term comparison. Similarly, this transect group experienced a long-term retreat of 4.3 meters in Dune Crest Position despite a short-term positional advance of 1.9 meters. Notably, the sound-side morphology here is more subtle than that of the Gulf side, with average Dune Crest Heights of just 1.5 meters compared to 3.3 meters, as surveyed in 2024. As such, the sound side Dune Crest retreat was more consistent with the high rates of shoreline retreat shown in Table 4 above, as these two morphological features moved landward in tandem.

West Petit Bois Island was represented with a single cross-island topographic transect. It is presented separately here and in Table 5, as it is bisected from Petit Bois Island by Horn Island Pass. Here, the long-term signature is that of loss in Profile Area, high variation in Dune Crest Position on the Gulf side, and, recalling from the previous section, a high rate of shoreline retreat.

Topographic Change Florida

Similar to the Mississippi Islands, topographic profile change varied spatially within and between the two focal areas in Florida (Figure 9). Average changes in the key topographic metrics for Fort Pickens and Perdido Key are shown in Figure 8B. Net change values and annual rate of change values are in Table 5. Major findings for Fort Pickens and Perdido Key are listed separately below, and detailed topography plots for each survey event are included in Supplemental Materials Document 2 (SM2).

Different colored bands represent varying amounts of change, in meters. Shoreline change classes are consistent in Figures 6 and 7, but they differ in Figure 9. All insets are presented at the same scale (grey bar 1 meter tall and 420 meters long).

Fort Pickens Dune Crest Positions advanced 0.9 meters in the short term and 3.1 meters in the long term. The long-term advance was heavily influenced by transect fp11, where a new foredune crest was shaped 9.4 meters seaward of the 2018 crest position. Profile Area gains were also made in both short- and long-term comparisons, at one percent and three percent, respectively. Change in Dune Crest Height averaged 0.08 meters in the short term and -0.15 meters in the long term. The long-term loss is heavily influenced by transect fp07, which is located at beach access point 17A, a particularly thin part of the Fort Pickens Area where the shore-to-shore distance is just over 200 meters. Here, the primary dune crest was reduced from 3.3 meters to 2.0 meters between 2018 and 2024 (SM2). Altogether, the topographic feature measurements at Fort Pickens indicate either stability or an ability to recover from storms. However, as reported in Table 4, the shoreline retreated 17.3 meters overall.

Perdido Key average Dune Crest Position fluctuated markedly, with an 8.1 meters advance in the short term but a loss of 20.3 meters in the long term. This average is heavily influenced by transects pk07 and pk10. In both cases, the foredune crest present in 2018 was reconfigured by intense storms in 2020. The 2022 retreat in Dune Crest Position, followed by an advance, is echoed in Dune Crest Height and Profile Area losses and subsequent gains, indicating an overall pattern of recovery. Ultimately, the averages for Dune Crest Height and Profile Area were similar in 2018 and 2024.

Takeaways

Mississippi: There was an overall long-term gain in Dune Crest Height: 0.37 meters at Petit Bois Island and 0.30 meters at Horn Island. However, both Islands lost Profile Area, especially Horn Island (21%), and both Islands exhibited overall retreat in Dune Crest Position (Table 5). The sound sides of both islands experienced higher Dune Crest Positional retreat and percent loss in Profile Area. In summary, despite some short-term gains, both islands exhibit signatures of subaerial sediment loss. At Horn Island, the mean Dune Crest Height is 3.3 meters, while at Petit Bois, the height is just 2.4 meters. With the smaller stature of Petit Bois Island’s foredunes and shallower beach slopes, higher rates of shoreline displacement are to be expected. The more robust dunes and steeper beaches at Horn Island resulted in less shoreline retreat, but the island experienced heavier losses in Profile Area, often resulting from the displacement of the beach berm.

Florida: Like in Mississippi, the shoreline position retreated in the long term, with both Perdido Key and Fort Pickens yielding similar average long-term displacement lengths and rates. This latter detail puts the short-term shoreline advance at Perdido Key in surprising context, as it required almost one million cubic yards of sand to be mechanically deposited on its shores to maintain a long-term rate of loss similar to Fort Pickens. The high rate of shoreline and Dune Crest Positional retreat at Perdido Key is substantiated by FDEP (2024), which reports that about 150,000 cubic yards of sediment are sloughed off every year to downdrift currents.

The benefits of restoration at Perdido Key are shown in Figure 10. Sediment was placed on the Gulf beach along a stretch of about 3.5 miles (5.6 kilometers), leading to short-term shoreline advance. Sediment was also placed adjacent to Pensacola Pass, east of Robertson Island, resulting in the sandy tail shown in the map inset that hooks to the northwest.

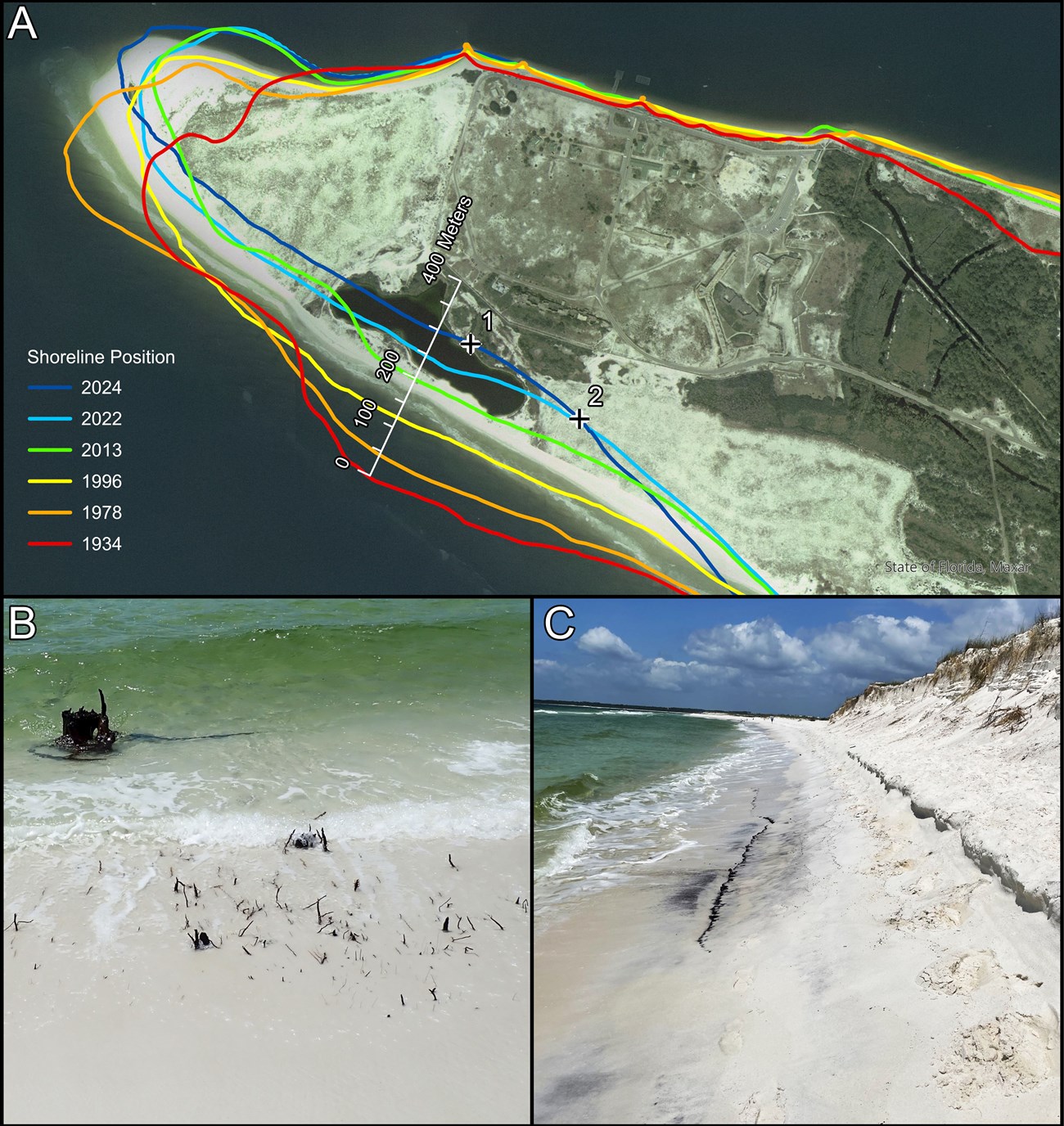

The Gulf-facing western tip of Fort Pickens has experienced a long-term pattern of shoreline retreat that has accelerated in recent years. An extreme case is shown along the scale bar in Figure 11. There, the long-term retreat rate from the 1930s to 2024 was over three meters per year, but within the past two years, it jumped to roughly 25 meters per year. This rapid shoreline retreat has uncovered organic material, including pine tree stumps that were buried after Hurricane Ivan in 2004. The 2003 aerial image shown in Figure 11 reveals that the pond and its associated vegetation near Battery Payne have mostly succumbed to the Gulf. The recently published study by Olsen (2023) found similarly high rates of retreat in this area, approximately 6 m/year from 2005 to 2021.

Photos B and C were taken during shoreline surveys in 2024. Shoreline position records from 1934 and 1978 were made available by Himmelstoss (2017).

This is the third in a continuous series of every-other-year reports related to monitoring shoreline and topographic change at Gulf Islands National Seashore. Geomorphology surveys at the park will be repeated in 2026. It is expected that future reports will benefit from the accumulation of data sets, allowing for better interpretation of the measurement variations attributed to geomorphic differences (e.g., slope), as well as weather, seasonal, and tidal differences.

Article created by Jeff Bracewell, GIS Specialist for the Gulf Coast I&M Network

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials to this report are available in the NPS datastore, as are all previous project briefs. Follow the link below for the 2024 Supplemental Materials (NPS internal downloads only) and links to all other project materials.

Anderson, S. M., A. Feldmen, A. James, C. Katin, and W. R. Wise. 2005. Assessment of coastal water resources and watershed conditions at Gulf Islands National Seashore (Florida and Mississippi). Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2005/330.

Bracewell, J. 2017a. Monitoring coastal topography at Gulf Coast Network parks: Protocol implementation plan. Natural Resource Report NPS/GULN/NRR—2017/1522. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2244086 (last accessed October 2024).

Bracewell, J. 2017b. Monitoring shoreline position at Gulf Coast Network parks: Protocol implementation plan. Natural Resource Report NPS/GULN/NRR—2017/1501. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2243708 (last accessed October 2024).

Bracewell J. 2023. Coastal topography change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2022 data summary. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado (last accessed October 2024).

Cooper, R. J., G. Sundin, S. B. Cederbaum, and J. J. Gannon. 2005. Natural resource summary for Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS). Final report to National Park Service Gulf Coast Network. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/ Profile/590835 (last accessed January 2022).

Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). 2024. Pensacola Pass Inlet Management Plan. Available at https://floridadep.gov/RCP/Beaches-Inlets-Ports, (last accessed October 2024).

Himmelstoss, E.A., Kratzmann, M.G., and Thieler, E.R.. 2017. National assessment of shoreline change – A GIS compilation of updated vector shorelines and associated shoreline change data for the Gulf of Mexico: U.S. Geological Survey data release. https://doi.org/10.5066/F78P5XNK.

Himmelstoss, E.A., Henderson, R.E., Farris, A.S., Kratzmann, M.G., Bartlett, M.K., Ergul, A., McAndrews, J., Cibaj, R., Zichichi, J.L., and Thieler, E.R.. 2024. Digital Shoreline Analysis System version 6.0: U.S. Geological Survey software release. https://doi.org/10.5066/P13WIZ8M.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2023a. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Local Climatological Data Station Details. Available at: ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/datasets/LCD/stations/WBAN:12926/detail (last accessed October 2024).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2023b. The Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services. Available at: tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov (last accessed October 2024).

Olsen Associates (Olsen). 2023. Inlet Management Study, Pensacola Pass, Escambia County FL. April 2023.

Psuty, N. P., T. M. Silveira, M. Duffy, J. P. Pace, and D. E. Skidds. 2010. Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network geomorphological monitoring protocol: Part I—ocean shoreline position. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/664308 (last accessed October 2024).

Psuty, N. P., T. M. Silveira, A. J. Spahn, and D. Skidds. 2012. Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network geomorphological monitoring protocol: Part II - coastal topography. Natural Resource Report NPS/NCBN/NRR—2012/591. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/604476 (last accessed October 2024).

Segura, M., R. Woodman, J. Meiman, W. Granger, and J. Bracewell. 2007. Gulf Coast Network Vital Signs Monitoring Plan. Natural Resource Report NPS/GULN/NRR–2007/015. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at: DataStore - Gulf Coast Network Vital Signs Monitoring Plan (nps.gov) (last accessed October 2024).

Other Reports in this Series:

- Coastal topography change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2021 data summary-version 1.1: DataStore - Coastal topography change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2021 data summary—version 1.1 (nps.gov)

- Shoreline change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2021 data summary: DataStore - Shoreline change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2021 data summary (nps.gov)

- Coastal topography change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2022 data summary: DataStore - Coastal topography change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2022 data summary (nps.gov)

- Shoreline change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2022 data summary: DataStore - Shoreline change at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida and Mississippi: 2018–2022 data summary (nps.gov)