Last updated: May 9, 2023

Article

Virginia: Group Escape, November 26, 1775

A Promise of Liberty: as colonists revolted, the British offered freedom to those enslaved by rebels. Six men in Virginia risked everything to answer the call.

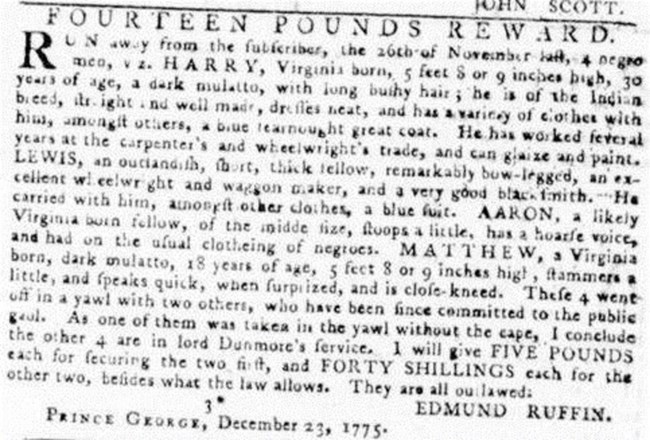

In a daring escape attempt early in the American Revolution, six enslaved men slipped away from a Virginia plantation, commandeered a two-masted fishing boat, and headed east toward the port town of Norfolk, Virginia. Their enslaver, plantation owner Edmund Ruffin, placed a newspaper advertisement for their capture soon after their escape in late 1775. In the ad, Ruffin surmised the group hoped to join British forces led by the exiled British governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore.

Dunmore had issued a proclamation three weeks prior promising freedom to anyone enslaved by “insurrectionists” who would fight for Britain. Not only would he gain fresh troops to retake the colony from revolutionaries, he might break the will of slaveowners by depriving them of laborers while stoking fear of a slave rebellion.1 As psychological warfare, Dunmore’s proclamation backfired. As historian Benjamin Quarles noted, Dunmore quickly became “the first full-fledged villain” in “the American patriotic tradition.”

Efforts to deter freedom seekers from joining the British included slave patrols, newspaper letters and editorials suggesting the British were reneging on their promises, and a declaration stating those who didn’t return to their enslavers would be punished.2 Only four of the men were named in Ruffin’s ad: Harry, Lewis, Aaron, and Matthew. Harry and Matthew were described as being “dark mulatto.” Harry, Ruffin reported, was of Native descent. Harry was a carpenter, wheelwright, glazer, and painter. Lewis was also a wheelwright, as well as a wagon maker and blacksmith.

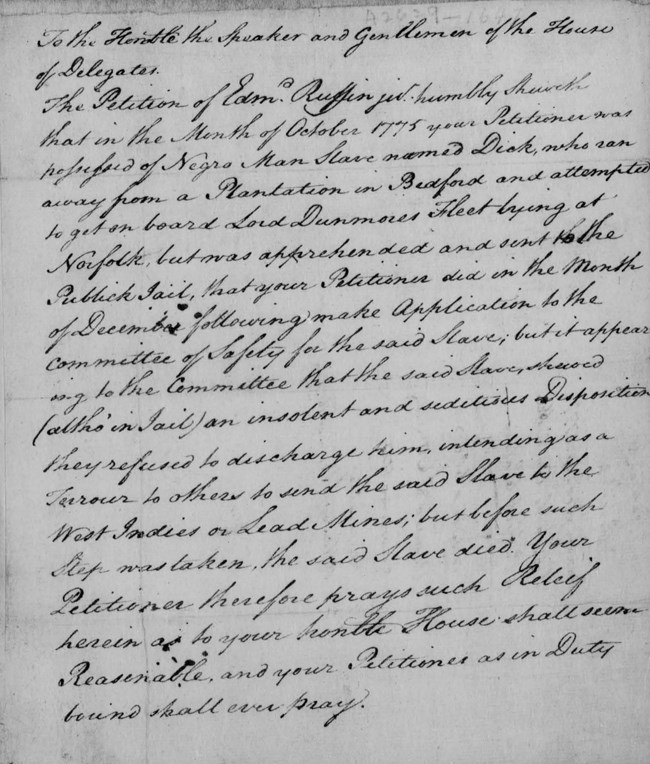

The four named men were believed to have reached Dunmore’s encampment, where they likely would have joined other freedom seekers in what the British called “The Ethiopian Regiment.” Two petitions made by Ruffin to Virginia officials reveal further information about the two men left unidentified in the ad. Their names were Dick and Joe, and according to Ruffin, both were intercepted before reaching their destinations. According to Ruffin, Joe “found means to make his escape leaving the others at Mulberry Island, & was soon after taken up on land & brought to this city....” Ruffin wrote that Joe was returned to him after he paid an “imprisonment fee.” However, the Virginia “Committee of Safety” declined to return Dick to Ruffin. Ruffin appealed the decision, but to no avail.

Ruffin explains what happened next in a petition sent to the Virginia House of Delegates on December 24, 1777.3 This remarkable document sheds light on the stunning cruelty awaiting any freedom seeker daring to flee Virginia’s plantations during the American Revolution.

In Ruffin’s appeal to Virginia legislators, he explained that Dick had not been released by the “Committee of Safety” because he “showed (altho’ in Jail) an insolent and seditious Disposition.” The Committee, Ruffin told legislators, had sentenced Dick to be sent to the West Indies or the lead mines in western Virginia, a common fate for those who were captured.4 Dick’s sentence was intended as “a Terrour [terror] to others,” he wrote. However, Ruffin noted, Dick died in custody before his sentenced was carried out. In petitioning the legislature, Ruffin didn’t bemoan Dick’s death while in custody. He simply wanted the Virginia legislature to pay for destroying his property.

By early 1776, Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment had nearly three hundred men wearing uniforms embroidered with the words “liberty to slaves”.5 Although the Ethiopian Regiment itself was soon disbanded, those soldiers were the first of an estimated 12,000 Blacks who served with British forces during the Revolutionary War. In 1777, the Continental Congress responded by rescinding a 1775 declaration that Blacks were ineligible to serve in the Continental Army, leading an estimated 5,000 African Americans to join the fight against the British.6

Many decades later, the Ruffin name would emerge on the national stage in the days before the American Civil War. The man credited with firing the first shot of the Civil War at Fort Sumter, arguably the most virulent of the “Fire-Eaters” calling for slave states to secede, was Edmund Ruffin’s grandson, Edmund Ruffin III.7

Author

Sydney Coleman and Network to Freedom

Sources

1 Frey, Sylvia R. (1991). Water From the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 63.

2 Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution. The University of North Carolina Press, 2012. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/43982.

3 Ruffin, Edmund Jr.: Petition (virginiamemory.com). See also: Paramour, Thomas: Petition (virginiamemory.com) This petition mentions a freedom seeker named Aaron sent to the lead mines for attempting to join Lord Dunmore

4 Edmund Ruffin, Jr.: Petition. http://rosetta.virginiamemory.com:1801/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2588319

5 Richard Johnson, Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment,” June 29, 2007. BlackPast.org. www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/lord-dunmore-s-ethiopian-regiment/

6 Douglas R. Egerton, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America, Oxford University Press, 2009.

7 Eric H. Walther, The Fire-Eaters (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992). See also: https://richmondmagazine.com/news/an-unyielding-man-04-26-2011/.