Last updated: January 31, 2024

Article

Green Book Historic Context and AACRN Listing Guidance (African American Civil Rights Network)

Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection, P 365, Box 12.

Introduction

Traveling with a minimum degree of safety and comfort is something we expect to be available to us now. Although the work to guaranteed civil rights for all is a continuing process, we may take for granted that we can stop to use the restroom, grab a meal, get gas, or find a place to stay overnight more or less whenever or wherever we need to along the way. But not very long ago, this was not expected, and certainly not taken for granted, by a large percentage of American citizens, African Americans. Thanks to entrenched and systematic racism that was pervasive throughout the country in the form of formal Jim Crow laws, segregationist policies, informal community traditions, or simply the bigoted and racist attitudes of individuals, African Americans always faced increased difficulties and frequently faced physical danger whenever they wanted or needed to take a trip away from home.

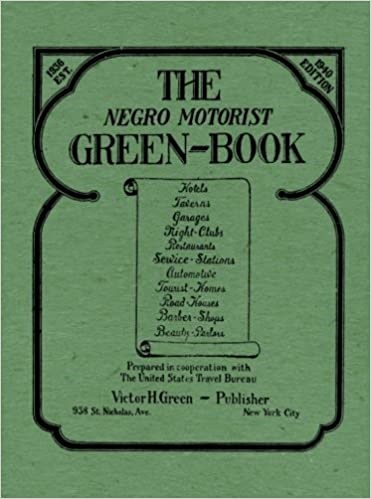

Attempts to thwart such hurdles largely fell on the individual or family, but there also were organized efforts, the most successful and long-lived of which was the Green Book. The brainchild of postman Victor Green and first published in 1936, it was called alternately The Negro Motorist Green Book, The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, and The Travelers’ Green Book over its 30-year existence. Dino Thompson, a native of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, succinctly and powerfully summed up the Green Book’s seminal importance to African American travelers: “...[it] didn’t tell you if a place had a good steak, or good seafood, or had a soft bed...it told you where you would be safe; it told you where you’d be welcome and not made to go around the kitchen and order something to go...The rest [of the guide books out there] are just fluff...To my mind, it’s still the only necessary travel guide that’s ever been printed.” Simple, fundamental, essential. The starting point from which a safe journey could be planned, and a tool for the African American community to actively resist the oppression they faced across America.

This objective of this document is to provide necessary historical information and guidance for property owners and others who know of a Green Book site, and are interested in having it become a member of the African American Civil Rights Network (AACRN). A recent survey of the locations of Green Book sites by ethnographer Candacy Taylor found that of the thousands of Green Book sites on record, only 5 percent are still in operation and more than 75 percent are gone. Due to the Green Book’s importance to the civil rights struggle, the study of it can shed light on not only the history of race in America but also on our society today. Given the perilous status of its physical manifestations, the AACRN has identified the Green Book and its sites as an area of particular interest.

To become a member of the AACRN, applicants must demonstrate a verifiable connection to the civil rights movement, usually done by writing a statement of significance on the application form. Because all Green Book sites share a common historical background, however, we are providing this context document for applicants to use in meeting that requirement. Guidance for how to do that will follow a brief historical overview of the Green Book. The overview is not meant to be an exhaustive history; it is intended only to establish historic significance for the purpose of meeting the AACRN criteria and simplifying the listing process for applicants. Suggestions for further reading will follow the listing guidance.

The New York Age, 23 August 1958, Saturday, page 32

Green Book Historical Overview

Postal employee Victor Green, with assistance from his wife Alma, started the Green Book in Harlem in 1936. The Greens headed up the project and its annual publication until 1962, with Alma taking over completely after Victor’s death in 1960. The final two editions, for 1964-5 and 1966-7, were published by former newspaper writer Langley Waller. The first two editions were heavily focused on businesses in Harlem, but it expanded to cover other regions and states quickly, and by 1962 had a circulation of over 2 million nationwide. Listings covered not only lodging and restaurants, but many types of businesses: hair salons, barbers, gas stations, haberdashers, tailors, vacation resorts, liquor stores, and many more. The Green Book impacted lives on many levels.

Its wild success was due to several factors. As Candacy Taylor has noted, the sites “reshape the story of black mobility and tell a story that is not all about struggle.” The Green Book put the power of decision and self-determination into the hands of both black business owners and travelers, celebrating entrepreneurship and proactive measures. Timing is also important to understanding its success; Green started the publication within an established context of protest and social action by African Americans eager to push back against discrimination. “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” (sometimes called “Buy Where You Can Work”) protests of the 1930s were held in many cities, including Harlem, and encouraged boycotts of stores that refused to hire African Americans. The agency that the Green Book afforded to individuals, to choose to support black-owned and tolerant white-owned businesses, fit perfectly within that framework. Owning a Green Book also allowed African Americans to take advantage of the freedom that should come with owning a car. The Green Book enabled its users to take advantage of that freedom with safety.

The Green Book was not the only black travel guide in existence; at least 6 others were on the market while it was in publication. Hackley and Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers was the first, established in 1930 by Edwin Henry Hackley and Sarah D. Harrison, but only in operation for one year. Others included Grayson’s Travel and Business Guide (begun 1937); Smith’s Tourist Guide (begun 1940); Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring (1952-1959); Travelguide (1947-63), whose motto was “Vacation & Recreation Without Humiliation; and, notably, two Roosevelt-era government guides: the National Park Service’s Directory of Negro Hotels and Guest Houses in the United States and the Department of Interior’s directory of black lodging for the “convenience of Negro Travelers.”

Establishing a consistent brand identity for his publication was therefore important for Victor Green, and the Green Book eventually took on a recognizable style and design. He also had a tool at his disposal that publishers of the other guides did not: a ready-made network of other postal employees. The Green Book, which was distributed by mail-order and sold by businesses, found success through word of mouth but also by an ambitious grass roots campaign of Green’s national network of fellow postal employees, who would solicit advertising from black-owned businesses along their routes.

An additional and important element to the Green Book’s success among competitors was Green’s relationship with James A. Jackson, an African-American marketing executive at Esso, today’s Exxon. Green and Jackson partnered to publicize and market the Green Book in a mutually beneficial process: Green printed an article in the 1939 edition about Jackson’s appointment at Esso, and Jackson ensured that all Esso stations throughout the country sold the Green Book. Esso was becoming increasingly well known as one of the most progressive large companies when it came to the treatment of black customers and employees. Not only were African-American motorists welcome at nearly all Esso stations, but Esso also employed black men as mail clerks, pipeline workers, and even gas station franchise owners. Endorsement from Esso of the Green Book had a nationwide reach, and it carried weight with many African-American consumers.

Green Book Evolution

Changes in the Green Book’s title throughout its history—Negro Motorist Green Book, Negro Travelers Green Book, Travelers Green Book—reflect its evolution as a publication. The focus of most of the business listings and travel essays was travel by car. Having a car meant freedom to an entire country of middle class consumers, particularly following World War II and the burgeoning economic prosperity of the United States. But to African Americans, owning a car had the added significance of providing a degree of protection from both the potential physical and emotional harms of traveling through America’s segregated public spaces. The real and immediate threat associated with getting stranded in one of thousands of “sundown towns”, all-white communities that banned black people from entering after dark, represented one extreme of the types of danger motorists could encounter. But even if physical harm was not an issue, the potential harassment one could face or the humiliation associated with, for example, being forced to go to the back door of a restaurant, was significant. The Green Book tried to help motorists avoid all types and degrees of harm.

Before expanding on the Green Book’s evolution, it is important to recognize that through its listings, the Green Book did not only attempt to mitigate potential problems. By giving individuals the opportunity to choose to patronize businesses that would treat African American customers with respect and dignity, the Green Book gave agency to its readers. Similarly, it allowed business owners to target an interested client base. Collectively, it enabled travelers and businesses to harness unified economic power to push back against oppression and harassment. That Victor Green chose to include businesses such as golf courses, country clubs, state and national parks, and other recreational pursuits also celebrated activities beyond just basic survival. It tried to elevate the traveling experience from survival to enjoyment, and eventually to social action.

In nearly every respect, the Green Book was not a static publication. As both modes of travel and the political atmosphere evolved, the Green Book’s publishers took note and made adjustments accordingly. The list of participating businesses changed and expanded regularly, necessitating both changes in design and increases in price, eventually containing entries for over 10,000 businesses over its lifetime. Rationing of supplies during World War II necessitated a hiatus in publication for four years, but it started the post-war period in 1946 with a makeover. For the first time, the 1946 cover contained an illustration—a cityscape—and all subsequent editions had an illustration or photo on the cover. The well known tag line--”Carry your Green Book with you...you may need it”--also appeared for the first time in 1946.

Special editions focusing on different modes of travel appeared periodically, including one on rail travel in 1951 and another on air travel in 1953. Train travel not only represented adventure and new experiences, it provided a connection to the largest private employer of African Americans in the country, the Pullman Company. Accordingly, the 1951 issue, with its cover emblazoned with a speeding train, contained an illustrated article, “The American Railroad,” complete with images of crisply dressed and attentive Pullman porters in action. Though the article’s rosy language painted what could be considered an overly optimistic picture of train travel for African Americans, given the reality of segregated train cars and unequal accommodations, it presented an aspirational vision, appealing to the sense of freedom and the potential for a new life that trains represented for many.

The 1953 “airline edition” aimed to demystify international travel and make it accessible for more people. Similar to the railroad issue, the airline edition featured a multi-page, illustrated article on air travel, calling air transportation “the miracle of modern travel.” It highlighted three airlines—Pan American, American, and Trans World. Continuing a partnership Green had begun in 1949 with Maher Travel Bureau in New York City to facilitate Green’s “Reservation Bureau” for international travel, the 1953 and subsequent editions of the Green Book included information on travel to and listings in numerous foreign countries, including 30 African countries by the1963-4 edition.

Over its 30 years, the Green Book existed within a rapidly changing environment for race relations in the United States, which is reflected in shifts in tone and content, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s. But as early as 1947, in the face of black World War II veterans being denied entry to white colleges, the Green Book listed 106 black schools and colleges, broken out by state. An article titled “Money for Negro Colleges” preceded the list, reprinted from the New York Times. It made the case not only for access to higher education for black veterans, but also for financial support for the colleges listed. The justification for access and support was pointed, and broad:

“The educated Negro was once a rarity. His numbers are increasing year by year, and his contributions to the arts, science and education steadily gain a wider and juster recognition for his abilities. From these we all gain, regardless of color. And, as we mutually put a proper, unprejudiced estimate on the contributions of all races to the common good, we move surely closer to the goal of living together in harmony.”

By reprinting this entreaty and listing the colleges, the Green Book was actively and overtly inserting itself into politics, an unusual move for the publication at least until several years later. Though publication of the Green Book was itself a political and social act, as it encouraged African Americans to take charge of their opportunities, it usually did so in a more subversive, indirect way.

Encouraging patronage of black-owned businesses did nothing to directly challenge segregation, after all. But with this appeal, the publishers made the direct connection between advancement of the African American population and the good of the entire country, and directly challenged white supremacy.

Beginning with the 1956 edition, the Green Book underwent a dramatic change in layout and content. It stopped listing gas stations, drugstores, tailors, hair salons, and liquor stores, among other establishments, and focused solely on lodging and restaurants, with few exceptions. Notably, this occurred shortly after the 1954 landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ruled racial segregation of public schools unconstitutional. Significant as the ruling was, it did not sweep away segregation overnight. But despite the difficulty in implementing the ruling due to white backlash in several states, did Victor and Alma Green feel that it represented significant enough progress in racial integration that the listings for hair salons and the like were no longer necessary? The articles within the 1956 edition give no indication, but with this change, the Green Book was truly aimed at the traveler, as opposed to the community as a whole.

The first indication that the changes in the 1956 and later editions of the Green Book reflected an acknowledgement of and nod toward the changing political and social landscape comes in an article on page 69. It is the first of several forthcoming articles that explicitly recognizes the changes and exhibits an increasingly more activist tone than had been seen previously, with the exception of the 1947 entreaty on behalf of higher education for returning black veterans. The 1956 article recounts the efforts of the Nationwide Hotel Association to encourage black hotel owners to improve their properties to make them as attractive to travelers as other hotels, made necessary due to increasing integration:

“Today we are making rapid strides in the field of interracial relations. In almost every section of the country color barriers are being broken down...from the beginning we planned only to serve the Negro public; we had a monopoly. As a result the Negro Businessman is not prepared to enter the market for all people.”

While not yet making overt political statements in support of desegregation, the Green Book was acknowledging the changing world and encouraging black business owners to prepare for it.

Overt support of desegregation would come five years later. Editor Novera Dashiell wrote openly with clear approval in the 1961 edition of the impact of sit-ins across the country. There is little doubt she was referring to the work of Ella Baker to organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) when she wrote:

"Every age across recorded time had its minority group pinioned in the talons of prejudice. Each race had its torch-bearers. History shows the rewards gained when a race made its own struggle against the ebb and flow of local and national passions. No one esteems freedom given or sought without it being earned...1960 has been quite an eventful year for Negroes in both domestic and foreign affairs. Our young generation with their successful sit-in demonstrations have prodded the older generation to greater effort in the struggle for civic identity.”

Going even further, the 1963-64 edition of the Green Book featured a direct effort at making the gains in civil rights actionable for the traveling public, with an article on page 2 entitled “Your Rights, Briefly Speaking”--a state-by-state summary of civil rights laws. For example, in Alaska: “Anti-jimcro law in recreational facilities. Violators are subject to criminal punishment (court proceedings)”; in Illinois: “Anti-jimcro law in recreational facilities, including discriminatory advertising. Violators subject to civil damages, criminal punishment and injunction (court proceedings)”; and in Virginia: “Prohibition of advertisements discriminating because of religion. Violators are liable to injunction suits (court proceedings).”

The laws and punishments varied, but the Green Book traveler could be assured of knowing what was possible, and where. No longer simply taking the approach of avoiding conflict, it encouraged its readers to know their rights, stand up for them, and fight back:

“...the Negro is only demanding what everyone else wants...what is guaranteed all citizens by the Constitution of the United States.”

As hard fought and longed for as the gains in civil rights were, there were unintended detrimental consequences for black-owned businesses. The final, 1966-7 edition excitedly told the reader of the 1964 Civil Rights Act: “...a new bill of rights for everyone, regardless of race, creed, or color. Public Accommodations: Effective at once, every hotel, restaurant, theater or other facility catering to the general public must do exactly that.” Despite the frustratingly incremental application of, or even outright defiance of the Act by many, desegregation afforded white business owners an expanded customer base, and the Green Book included listings for white-owned luxury hotels and clothing stores that hadn’t been accessible to African Americans previously. Expanded access and expanded choice, however, had the practical effect of driving business away from many Black-owned establishments, and eminent domain used by governments to seize land for urban renewal and freeway projects added to the problem. Majority Black neighborhoods across the country, containing unknown numbers of Green Book businesses, were razed in the name of ”progress.” Others, now bypassed by the newly constructed freeways that took potential customers away, suffered economic devastation that left formerly thriving urban areas mere shells of what they once were. At least half of the Black-owned businesses in the Green Book were closed within 10 years.

South Carolina Political Collections, University of South Carolina

Women and the Green Book

No discussion of the Green Book is complete without addressing the involvement of women. It began from the start of the Green Book’s production, with Victor Green’s wife, Alma. She was not credited as editor and publisher until 1959, but there is little doubt that her impact had always been significant and long-lasting; Victor, after all, also held down a full-time job as a postman for thirty-nine years. Alma had ample opportunity to contribute, and eventually ran the entire operation. By 1959, four of the five staff members listed on the title page were women: Novera Dashiell, Assistant Editor; Dorothy Asch, Advertising Director; Evelyn Woolfolk (who had worked for Greene, with a hiatus, since the 1930s), Sales Correspondent; and Edith Greene, Secretary. The gender of the fifth, Travel Director J.C. Miles, is unknown due to the use of initials. Dashiell has the only articles in the Green Book with a byline, an indication of the importance of her influence, in particular, on the content. Her writing was energetic and approachable, but she also used a more political tone than Victor Greene ever had. Her attention to civil rights activities was noted above, but she also made note of the political circumstances in foreign countries, using the platform to advise readers on the relative safety of many potential vacation locations.

Domestically, the Green Book was an avenue for black women to defy traditional gender roles and achieve a measure of independence by having their businesses listed. Though women owned or managed many types of listed businesses, a few were particularly noteworthy in their importance and or pervasiveness. They also are illustrative of the characteristics of so many women’s contributions to the civil rights struggle: impactful, family and community-oriented, ubiquitous, and often overlooked. First, “tourist homes,” or private residences with a room to rent, provided lodging options where hotels for African Americans were sparse or non-existent, and most of them were owned or operated by married or widowed women. Tourist homes had become a popular way for all people to earn income in the Great Depression, but for African Americans they addressed an additional need: safety. For the women who ran them, they also meant a measure of economic independence. Tourist homes were also ideal locations for building social networks, a critical element of the community organizing so important to civil rights activities. The Green Book listed over fourteen hundred tourist homes throughout its existence; in fact 90 percent of all Green Book sites in Nebraska and Michigan (except for Detroit) were tourist homes.

Salons and beauty colleges, traditionally women-owned and/or operated, demonstrate the two-pronged effect of the hair industry. In a reflection of their ubiquity, hair salon listings frequently outnumbered lodging and food listings in many Green Book cities. The hair salon as a safe gathering place was a long-standing tradition, effectively making community luminaries out of hair stylists. Some salons doubled as safe spaces for community development during the formative years of the civil rights movement, but salon employees also took more active roles such as driving clients to voting booths or allowing NAACP literature to be delivered to the salon rather than to clients’ homes, since the NAACP was considered a radical organization. Beauty colleges created products specifically for black women’s hair, and trained thousands of women to run their own businesses. We cannot overestimate the importance of these businesses to the economic freedom and personal development of black women, and by extension of the families and communities they supported. Candacy Taylor has noted that “As the automobile industry lifted black men out of poverty and into the middle class, the hair industry did the same for black women.” The Green Book contributed significantly to this phenomenon by providing a platform for advertising and directing customers to them.

Finally, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), played a crucial role in civil rights but also in women’s development, which buttressed civil rights activities. The YWCA encouraged its members to take a stand against lynching in the 1930s, and worked to end segregated housing by the 1940s. As an organization specifically for and dedicated to women, the YWCA provided safe lodgings but also fostered their personal and professional development in addition to the community-wide impacts of its civil rights activities. The Green Book acknowledged its place in communities by listing forty-seven of them.

There are so many more stories of women in Green Book history; it is not possible to discuss them here. This section is intended to introduce the reader to a few examples of how the Green Book supported and empowered black women at a time when they were often considered second-class citizens. A look through its editions will hint at the important roles women played in their families and local communities. These arenas are not as commonly acknowledged for their contributions to the fight for equality as the more visible sit-ins, demonstrations, and protests usually pictured. However, the family unit or local business was frequently the cradle of what grew into those visible activities. The Green Book’s pages highlight not only the businesses, but the powerful and formidable women behind them, such as Geneva Haugabrooks of Huagabrooks Funeral Home in Atlanta; Alberta Northcutt Ellis, proprietor of Alberta’s Hotel in Springfield, MO; and Modjeska Simkins, who ran the Hotel Simbeth in Columbia, SC. Let the Green Book listing be a starting point for research into the lives of these fascinating women, and a reminder that power and influence take many forms.

National Park Service

The Green Book and the African American Civil Rights Network: Listing Guidance

The objective of this document has been to demonstrate the significance of the Green Book to the story of civil rights in the United States, for the purpose of listing a property in the African American Civil Rights Network (AACRN, the Network). The Network was created in 2017 (see note 2), with the aim of creating a publicly accessible repository of information about the people, places, and stories important in the African American Civil Rights movement. To do this, three types of eligible Network members have been identified: properties, the physical location of a civil rights event, or a location associated with a person or organization important to the movement; facilities, historic or modern locations dedicated to telling a civil rights story; and programs, a tour, educational program, exhibit, website, or other way the civil rights story is presented to the public. The AACRN website has more information and examples about how to join the Network. We hope that this document will facilitate the listing of members who were Green Book businesses, by easing the documentation burden for Green Book applicants.

The AACRN application form has three pages of required information. Most is basic identifying information such as resource location and contact information. The final piece requires establishing historic significance, the task this document is intended to address. Establishing significance is the most important part of the process, whether for a Green Book site or any other potential member. The AACRN application process is not a competitive one; any property that can be shown to have a connection to the African American civil rights movement (plus permission of the property owner) will be accepted. Without this document, an applicant would need to conduct research and write a 1200-word statement explaining the civil rights significance of the Green Book and making the subject property’s connection clear, but this document accomplishes most of that task for the applicant. Please follow the steps below for Green Book properties. If you have any questions, AACRN staff is able to assist.

- Complete page 1 and the ownership information on page 2 of the application form according to the application instructions.

- On page 2, in answer to the following instruction: For all types of Resource, describe it and the history of its association or significance to the African American Civil Rights Movement in less than 1200 words, simply write “This property was a participating business in the Green Book. Historic significance is reflected in the Green Book Historic Context.”

- Follow the above statement with information specific to the property being nominated. Please keep this section to 1200 words or less. Include:

- business type (for example, hotel);

- years in operation;

- year(s) property appeared in the Green Book;

- owner or proprietor while it was in the Green Book;

- current business, if still in operation; or “vacant” if vacant;

- Any other information you wish to include about the property.

4. Provide additional information as instructed on page 3.

Once the application form has been completed, submit it, any attachments, and the property owner consent letter as instructed on the Application and Instructions webpage.

Further Reading

This historic context has introduced the history of the Green Book only for the purpose of establishing significance for the African American Civil Rights Network. Those interested in a more thorough history have a wealth of additional primary and secondary sources at their disposal. First, and most important, are the editions of the Green Book themselves. Nothing can rival seeing the original material. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library has digitized copies of every addition available for free viewing, as well as a research guide and blog entries about the Green Book. It is an excellent place to start.

Additional information can be found in various types of media. Several State Historic Preservation Offices, Historical Societies, or other organizations have collected information on Green Book sites or history specific to a state or region. Good examples are in Virginia and Maryland. The National Tust for Historic Preservation also has a nationwide site dedicated to Green Book history, with a focus on preserving sites. The Smithsonian Channel produced a documentary in 2019 titled “The Green Book: Guide to Freedom.” It is available through local cable providers and on many streaming platforms. These are but a few examples; there are many more out there. However, simply typing “Green Book” into a search engine is likely to bring back several results on the 2018 film of the same name that will display first, so try being a bit more specific with searches by using the name of a state or a city, or even the word history. That should eliminate most results about the film.

The most comprehensive history of the Green Book to date is the 2020 book Overground Railroad: the Roots of Black Travel in America by Candacy Taylor, referenced several times in this document. The result of several years of research conducted by Taylor across America, it painstakingly lays out in both chronological and thematic fashion the details and stories of the publication, but also the people behind it and in it, and makes clear the immense impact the Green Book had on African American life and society throughout its existence. Overground Railroad also contains a state-by-state Green Book site tour and bibliography. It is an indispensable resource.

Finally, although not exclusively a Green Book topic, sundown towns are intimately connected to its history, and one of the most critical elements of segregated America that the Green Book could be used to avoid. It is at one extreme of the dangers faced by traveling African Americans, but is nonetheless often not understood or appreciated. Sundown towns were much more common and more a Northern and Western phenomenon than is generally understood. Sociologist James W. Loewen’s book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism is a thorough treatment of the historical and sociological elements of this topic. It would make a useful companion to Overground Railroad.

Conclusion

The Green Book is an indelible part of African American history. The segregation and racism that made it necessary impacts all Americans, not just African Americans, so the Green Book has something to teach us all. Victor and Alma Green were reacting to a need they saw, perpetuated by the systematic and casual racism in which the country was mired. Progress has been made, to be sure, but the climb toward civil rights is not over. Studying the Green Book and working to preserve its sites reminds us that the work to achieve equality is not always done with fanfare, or in obvious ways—it can be subversive, subtle, under the radar. So many former Green Book properties exist under the nose of their communities, who have no idea the impact that humble or out of the way places could have on a national story. Use this document to assist you in shining the spotlight of the AACRN on these lesser known properties, so that they might be understood and potentially preserved, and with them, the important history they reflect. AACRN staff are available to assist in the application process or to answer questions about the Network.