Last updated: June 7, 2025

Article

Grave Matters: Recovering the Lost Battle Dead of Milliken’s Bend

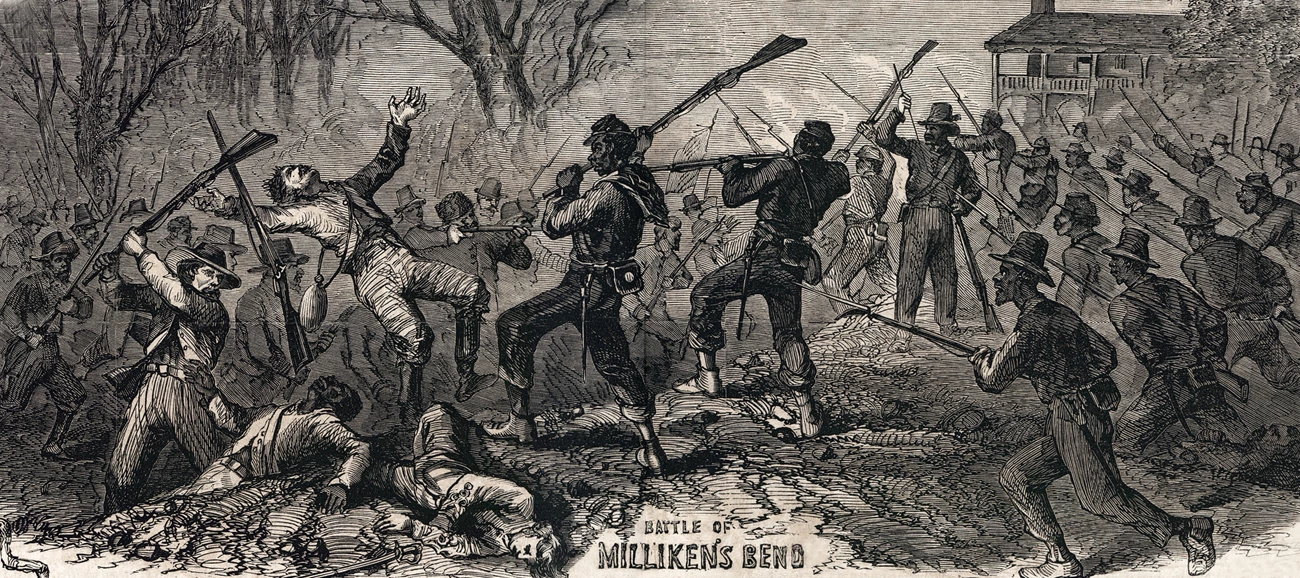

"Battle of Milliken's Bend from Frank Leslie's '"The Negro in The War," January 1863, artist's impression, zoomable image, detail," House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/41476

Article written by Isaiah Tadlock, MA

NPS Photo

On the sweltering summer morning of June 7, 1863, one of the most savage small engagements of the Civil War took place on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Located slightly north of the Louisiana town of Milliken's Bend, the battle saw some 1,300 men of the newly formed United States Colored Troops square off against a better trained Confederate force from Texas. Four regiments comprised what was known as "The African Brigade," including the 9th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, the 13th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, and the 1st Mississippi Infantry, African Descent.

Fighting for Their Freedom

The fighting lasted from dawn until noon, with the barely trained African Brigade shocking their opponents and their own officers with the ferocity of their defense. The freshly minted soldiers endured multiple gunshot and bayonet wounds, in addition to incidents of friendly fire from their supporting gunboats. They also fought at close quarters, not only with their bayonets, but using their own guns as clubs to repel the Confederate attack. It was the first time that any of them were able to strike back, after a lifetime of forced obedience, and many paid for those glorious few moments with their lives.

General Henry McCulloch, who led the Texans at Milliken's Bend, wrote the following day in his report that those men had fought with "considerable obstinacy." Diarist Kate Stone, the resident of a nearby plantation, wrote when news reached her that "It is said that the Negro regiments fought there like mad demons, but we cannot believe that."1

Isaiah Tadlock

Caring for the Wounded

The Confederates, unable to make further headway without taking deadly fire from the gunboats, fell back to nearby Richmond, Louisiana. The tattered remnants of the African Brigade found their return to camp a gruesome one. The bodies of the dead, dying, and badly-wounded were scattered along the line of their recent retreat. The levee that marked the western boundary of the camp had seen the hottest part of the fight, and there the torn bodies of friends and foes lay intermingled in death.

For the able-bodied men that remained, two tasks now took precedent: the transportation of the wounded to hospitals, and the burial of the dead. To aid in the former of these tasks, the hospital ship City of Nashville arrived, seemingly taking the severest cases. Others who, though badly wounded, seemed to be in no immediate danger of death were transported to a nearby "contraband" hospital, meant to care for former slaves. There, the men fell under the care of the 11th Louisiana's new Surgeon, Sylvester Lanning, some two miles to the south of their camp.2

Lanning, a 31-year-old Assistant Surgeon in the 48th Indiana Infantry prior to his transfer, soon proved to have a nasty temper with the men in his care. Joining his new command on May 20, 1863, he remained with it only until that October. Concerns were raised by both men and officers that Lanning was mistreating not only the hospital orderlies, but also the men he was supposed to be treating.

The final straw for his Commanding Officer seems to have been the report of how Lanning had treated his own servant. Lanning, in a fit of rage, struck the lad on the head with a rock, breaking his skull, and knocking him down. Colonel Van E. Young, commanding the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, condemned Lanning's actions as "conduct unbecoming an officer and highly detrimental to the welfare of the men." Lanning soon after left the regiment in disgrace and protested the acceptance of his resignation, as Colonel Young's acceptance notes detailed the doctor's misconduct. But by the time of Lanning's departure in October, many of the wounded had succumbed to their injuries under his care. Those who had were buried in the hospital grounds on the property of Alencon G. Powers.3

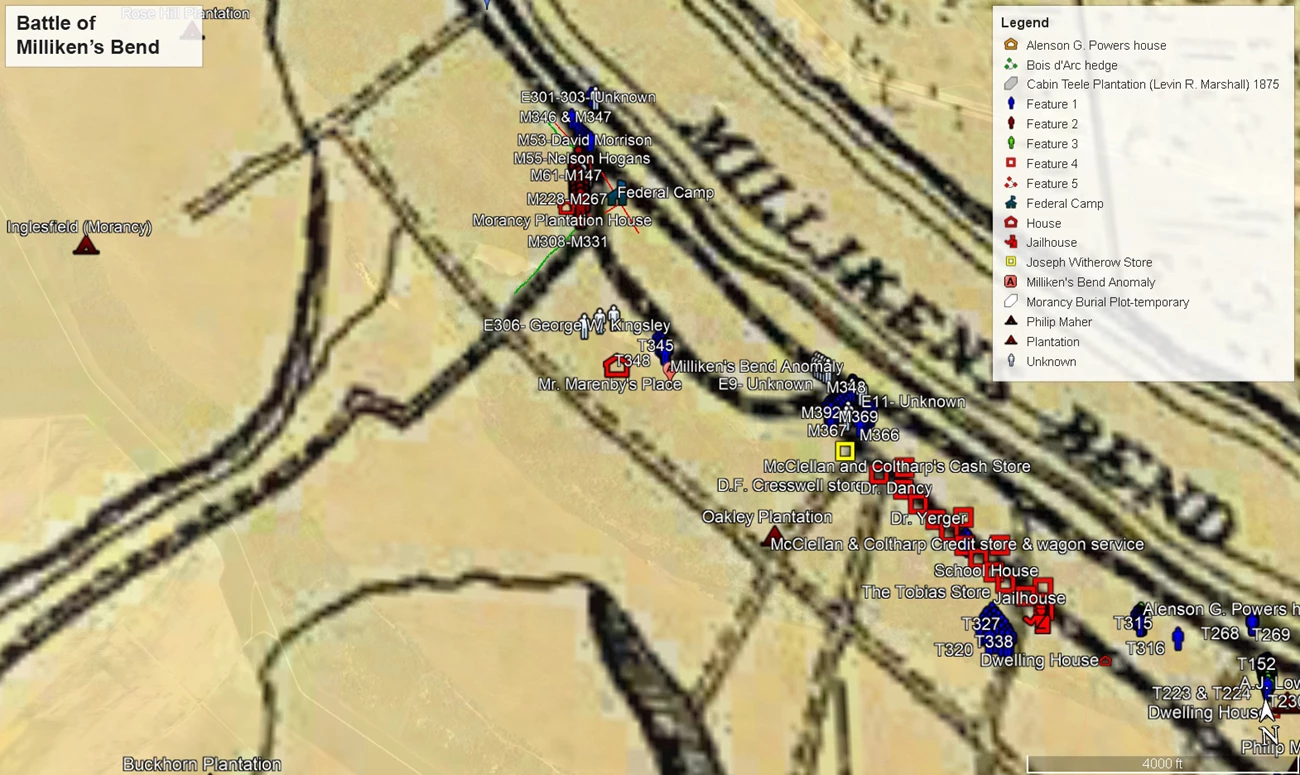

Burying the Dead

For the remainder of the men still at camp, there came the unenviable task of burying friends and in some cases, family. The Federal camp lay in sight of Morancy Plantation, and in a lot east of the main house, near where gaps had been cut for passage and firearms training, the victorious but grieving men of the African Brigade laid their comrades to rest. It is here that for over a century and a half, the identities of the dead and fatally wounded became obscured.

The regiments of the African Brigade remained at their camp until October at the latest. For the remainder of the war, with one exception, they were stationed in nearby Vicksburg. All except one – the 13th Louisiana, African Descent, which was soon disbanded – also received new designations. The 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent became the 49th United States Colored Infantry (USCI); the 1st Mississippi Infantry, African Descent became the 51st United States Colored Infantry (USCI); and the 9th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent became the 5th United States Colored Heavy Artillery (USCHA). For the next three years they lived almost in sight of that bloody field, and the graves of their fallen comrades.4

Detroit Publishing Co., Vicksburg National Cemetery, 17,000 Union soldiers buried here, Vicksburg, Miss. United States Vicksburg National Cemetery Mississippi. [Between 1910 and 1920] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016815547/

The year after the Civil War ended, the remaining men were mustered out and sent into civilian life as free men – or as free as Black men in the Reconstruction-Era South could be. In the aftermath of the Vicksburg Campaign, thousands of bodies of fallen Union soldiers still lay either unburied or in a pitiful state of rest. Those bodies buried in the vicinity of Milliken's Bend were also in danger of being lost permanently, due to erosion of the Mississippi's west bank.

The establishment of Vicksburg National Cemetery soon after provided a final, peaceful resting place for Vicksburg's fallen. Unfortunately for the dead from the Battle of Milliken's Bend, by the time the retrieval and reburial process began, so too had the cycle of growing cotton. In the field east of Morancy's Plantation house, the graves had been tilled over, leaving no trace of identification.5

Restoring Identities of "Unknowns"

Recovering the dead from Milliken's Bend, then, would seem almost hopeless. Yet clues to their location lay scattered throughout various records pertaining to them in their service records, Vicksburg National Cemetery's burial registers, the Union hospitals, and the reports and memoirs of the battle's survivors.

When reaching the burial ground at Morancy, the government agent overseeing the work wrote of a large number of bodies bound for Section M, that the bodies were "found in the lot east of the dwelling house – no head-boards – said to belong to the 9th Louisiana USCI Col. Lieb." Herman Lieb was the commander of the 5th USCHA and had been wounded in the leg at Milliken's Bend. This description covers burials M61-M187 – a total of 126 bodies.

John Schweikart / NPS Photo

Taken alone, this might seem like mere speculation. That is where four unknown white officers buried in Section E emerge. Burials E297-300 – now marked as E 1749, 1750, 1751 & 1752 – all bear the exact same location description as those buried in Section M, recognized as those belonging to Colonel Lieb. The records also state that the four were dressed as non-commissioned officers.6

Herman Lieb's after-action report of the battle lists four white, non-commissioned officers as killed in action that day. Lieutenant, later Major, David Cornwell of Lieb's command verified in his memoir that these men were intended to serve in these roles until enough men were enlisted to justify their promotion to the rank of lieutenant. Lieb recounted – and Cornwell after – the deaths of Lieutenants J. Brener, Henry Wetmore, and Thomas Walters, as well as Sergeants John J. Wine, Benjamin F. Perrine, and C.N. Cady. Both Thomas Walters and John J. Wine are buried in Ohio. Walters lies in Forest Cemetery in Fredericktown, and Wine lies in Saint Paul Lutheran Cemetery in Sonora.

The actual names of the men buried at Milliken's Bend are Jacob Bruner, Henry Wetmore, Charles N. Cady, and Benjamin F. Perrine. The report of Colonel Lieb, the service records of the 5th USCHA, and the pensions applied for by their wives, children, and mothers, all confirm that these men were indeed killed at Milliken's Bend. No burial record appears anywhere else for them. Also, the fact that most of these families applied for pensions indicates that they did not have the means to retrieve their dead.7

Since these are the officers of the 5th USCHA killed on June 7, 1863, this means that the men among whom they were initially buried were also the dead from that fierce engagement. However, not all of the Union dead of Milliken's Bend died on the field that day. Some lingered for days, weeks, and months afterward. Records show that these men died either in the "regimental hospital," or in "Van Buren hospital." For the men of the 49th USCI, these hospitals – likely one and the same – lay as previously stated, two miles south of the camp.

Section T of Vicksburg National Cemetery shows between graves 293 and 312 several individuals that stand out from the burials alongside them. These burials also happen to be on the grounds of Alencon Powers. The Burial Registers confirm that this house was used as a hospital. These bodies are listed as being buried in at least partial uniform, with one so fully kitted out as to be buried with his canteen.8

An almost equal number of men appear on the service records of the 49th USCI with the notation that they were buried "in their effects." Among these are Privates Henry Nelson, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Reuben Madlock, along with Corporal Jerry Johnson, and Sergeant Peter Bryant. A sixth, Private Alford Bishop is listed as having among his personal effects at death on July 7th, 1863, as a hat, blouse, flannel shirt, shoes, socks, and a knapsack, haversack, and canteen. T295 lists the deceased as being buried with "soldiers pants, blouse, [sic] woollen blanket & canteen." While Bishop's service record shows that his effects were in the possession of his company Captain for disposal, it also shows that he died of typhoid fever. This makes it unlikely that his Captain retained the contagious clothing – and especially not his canteen.9

The aforementioned five soldiers also all appear to be casualties of the fighting on June 7th. Yet one more compelling piece of evidence remains to indicate that Alencon Powers' house and garden was the hospital where Sylvester Lanning treated the soldiers in charge, and where the remaining dead were buried. 200 yards south of the house a lone burial was discovered; a body simply known as T316 (now T 9002). This body was found isolated, wrapped in a blanket, with a pump chain – for no obvious reason – buried with him. The ledger further notes that the skull was broken, making it appear that this is the unfortunate servant of Dr. Lanning. The chain was likely a last insult from a violent-tempered Army Surgeon to avenge his own exposure and disgrace. If this is indeed Lanning's servant, it is yet further evidence that the fatally wounded men of Milliken's Bend lay 200 yards north at the hospital.10

John Schweikart / NPS Photo

As of this writing, 161 years have passed since the bloody day on the levee. Milliken's Bend and the men who fought there have been largely forgotten. The men of the African Brigade have lain and languished, unknown. Yet, clues to their identities have existed almost as long as they have been buried. These men were among the first Black soldiers to strike for freedom, going head-to-head and hand-to-hand with men determined to keep them subdued – and denying them that victory.

The following men were buried as "Unkowns" at Vicksburg National Cemetery.

| Private Alford Bishop | Private Napoleon Bonaparte | Jacob Bruner |

| Sergeant Peter Bryant | Charles N. Cady | Corporal Jerry Johnson |

| Private Reuben Madlock | Private Henry Nelson | Benjamin F. Perrine |

| Henry Wetmore |

Private Alford Bishop

Alford Bishop was a 20-year-old recruit in the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent from Hinds County, Mississippi. He died of typhoid fever on July 7, 1863 while under the care of Dr. Sylvester Lanning. He is an unknown burial in Section T of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

Private Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte was a laborer from Waterproof, Louisiana before becoming a Private in the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent. He was fatally wounded at Milliken’s Bend on June 7, 1863, and died four days later. He rests unknown in Section T of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

Jacob Bruner

Bruner was a sawyer from Ohio before serving as a Quartermaster Sergeant in the 68th Ohio Infantry. He resigned to accept a commission in the 9th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, and was killed in action at Milliken’s Bend. Buried initially near the battlefield, he is one of four burials in Section E between 1749 and 1752.

Sergeant Peter Bryant

Peter Bryant was from Monroe, Louisiana, and was one of the first men given the rank of Sergeant in the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent. He was fatally wounded at Milliken’s Bend and died of the effects of his wounds on July 26, 1863. Buried initially in the grounds of Van Buren Hospital, he is now one of the unknown burials in Section T of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

Charles N. Cady

Born in Connecticut and a clerk before the war, Cady first served as a Sergeant in the 32nd Ohio Infantry before becoming an Orderly Sergeant in the 9th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent. He was killed at Milliken’s Bend by a musket ball through the head. He is one of four burials in Section E between 1749 and 1752.

Corporal Jerry Johnson

Jerry Johnson was originally from White River, Alabama before enlisting in the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent at Grand Gulf, Mississippi. He was wounded in action at Milliken’s Bend on June 7, 1863, and died of a related fever on July 16. He is one of the unknown burials in Section T of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

Private Reuben Madlock

Reuben Madlock was a 32-year-old recruit from Tensas Parish, Louisiana. He was wounded in the shoulder at Milliken’s Bend and died of his wound at Van Buren Hospital on July 11, 1863. He is one of the unknown burials in Section T of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

Private Henry Nelson

Henry Nelson was a 19-year-old Private in Company G of the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent. He was wounded in the shoulder at Milliken’s Bend and died of a secondary illness on July 15, 1863. He is one of the unknown burials in Section T of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

Benjamin F. Perrine

A Canadian by birth, Benjamin Perrine was a mechanic from Nova Scotia prior to becoming a Private in the 68th Ohio Infantry. Perrine was killed in action at Milliken’s Bend and buried near the battlefield. He is one of four officers buried in Section E between 1749 and 1752.

Henry Wetmore

Born in New York, he was a servant before serving as a Corporal in the 8th Illinois Infantry. Wetmore was killed in action at Milliken’s Bend and is one of four burials in Section E between 1749 and 1752.

After more than a century and a half, it is time to bring their identities to light.

1 Richard Lowe, Walker's Texas Division, C.S.A.: Greyhounds of the Trans-Mississippi (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004), 87-96; Linda Barnickel, Milliken's Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013), 86-101; John Q. Anderson, Ed., Brokenburn: The Journal of Kate Stone 1861-1868 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972), 219; United States. War Department. Confederate States Army Casualty Lists and Narrative Reports, 1874 – 1899, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington D.C. (Microfilm M836), see McCulloch's Report of Milliken's Bend.

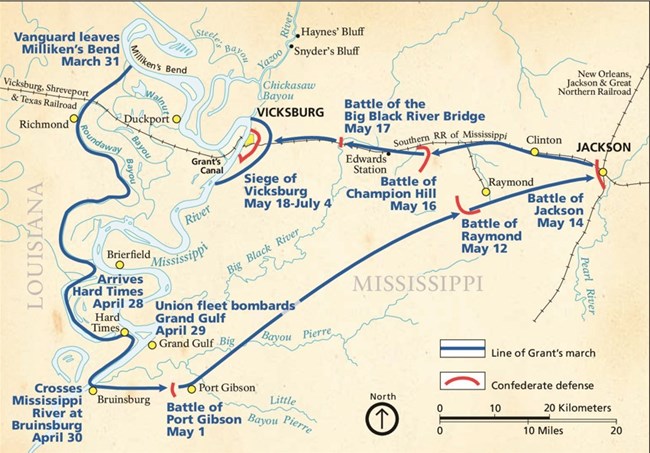

2 Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 47th-55th, Record Group 94, Roll 0032: Artillery Organizations, Record Group 94, Roll 0078, Miscellaneous Personal Papers, Record Group 94, Box 233, hereafter cited as Compiled Service Records of the African Brigade unless otherwise noted; Van Buren Contraband General Hospital, pp. 9-22, 193, Field Records of Hospitals-Louisiana, v.159 (entry 544), Records of the Adjutant General's Office (RG94), NARA, hereafter cited as Van Buren Hospital Records; Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Office of the Quartermaster General, Burial Registers of Military Post and National Cemeteries, compiled ca. 1862-ca.1960., NAID: 4478151, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985, Record Group 92, The National Archives at Washington, D.C., hereafter cited as Burial Ledgers of Vicksburg National Cemetery; Wilson, Js. H, Otto H Matz, and L Helmle. Map of the country between Milliken's Bend, La. and Jackson, Miss. shewing the routes followed by the Army of the Tennessee under the command of Maj. Genl. U.S. Grant, U.S. Vols. in its march from Milliken's Bend to the rear of Vicksburg in April and May. Washington, D.C., Lith. of J. F. Gedney, 1876. Map. The hospital ship, City of Nashville appears as the place of death in the service records of several men in the African Brigade from June 7 until June 15, thereby showing that the ship was nearby for a week before moving on. This seems to indicate that the ship, which could move from place to place as needed, was brought to a mooring near the camp at Milliken's Ben to triage and care for the severely wounded. Grant's Campaign map, stretched out over the modern landscape using remaining contemporary landmarks, indicates the camp as a mile north of the town. The burial ledgers of Vicksburg National Cemetery, which are enormously detailed, show the hospital as south of the town. The resulting approximate location places the hospital roughly two miles south of the camp.

3 Compiled Service Records of the African Brigade; Burial Ledgers of Vicksburg National Cemetery; Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Microfilm M653.

4 Burial Ledgers of Vicksburg National Cemetery; John M. Wearmouth, Ed., The Cornwell Chronicles: Tales of an American Life on the Erie Canal, Building Chicago, in the Volunteer Civil War Western Army, on the Farm, in a Country Store (Berwyn Heights: Heritage Books, 2015), 211-19; Compiled Service Records of the African Brigade; Cyrus Sears and the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Ohio Commandery, Paper of Cyrus Sears (Columbus: The F.J. Heer Printing Co., 1909), 12-13; The Weekly Telegraph (Bloomington, Il.), July 8, 1863. The 51st USCI was later reassigned, and took part in the assault on Fort Blakely, Alabama.

5 Richard Meyers, The Vicksburg National Cemetery: An Administrative History (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1968), 1-20; Burial Ledgers of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

6 Burial Ledgers of Vicksburg National Cemetery; Wilson, Js. H, Otto H Matz, and L Helmle. Map of the country between Milliken's Bend, La. and Jackson, Miss. shewing the routes followed by the Army of the Tennessee under the command of Maj. Genl. U.S. Grant, U.S. Vols. in its march from Milliken's Bend to the rear of Vicksburg in April and May. Washington, D.C., Lith. of J. F. Gedney, 1876. Map; Sears, 12-13; Wearmouth, 211-19. The burial ledgers also describe the location of other nearby bodies as being buried in an angle where the main road met the road leading to the dwelling house. An examination of Grant's Campaign Map overlaid on the modern landscape, taking into account the dimensions of the battlefield and proximity of the plantation house shows that these bodies were buried within sight of the battlefield.

7 The Weekly Pantagraph (Bloomington, Il.), July 8, 1863; The Weekly Pantagraph (Bloomington, Il.), November 4, 1863; Wearmouth, 215; US, Ohio, Soldiers Grave Registrations Cards, 1804-1958 [Fold3]; Findagrave.com, see Memorial Nos. 71694837 for Thomas Walters and 77272305 for John J. Wine; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., U.S., Civil War “Widows' Pensions,” 1861-1910, Record Group 15, see pension application No. WC105171 for Charles Cady, No. WC29244 for Jacob Bruner, and WC18198 for Benjamin Perrine; Compiled Service Records of the African Brigade. The pension records also indicate that Sergeant Cady was killed by being shot through the head, meaning that he was killed outright. His presence would seem to indicate that the other three were, as well. The Weekly Pantagraph of November 4 indicates that Quartermaster Charles Clark was taken on board a ship and died there. A search has not revealed his initial burial site, but it was likely further south near or in the Van Buren Hospital grounds.

8 Compiled Service Records of the African Brigade; Burial Ledgers of Vicksburg National Cemetery.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

NPS Photo