Last updated: April 30, 2024

Article

Grant Searches for a Civilian Career

Library of Congress

Upon resigning from the army in 1854 Ulysses made his way back to live with his family at White Haven. In giving up a stable career with the military, Grant was gambling that he would be able to find a steady civilian career in St. Louis. However, this proved more difficult than he could have ever imagined. Over the course of six years Grant bounced from one job to the next, but none earned him the financial security that he desired to support his growing family.

Farmer Grant

Ulysses S. Grant tried his hand at farming at White Haven in the mid-1850s. Initially he worked as a farm hand on the estate, but when Col. Dent moved to the city in 1857, Grant took full control of day-to-day operations on the farm. As a farmer Grant faced numerous obstacles including droughts, personal illness, a failing economy and unseasonable frosts due to the “Little Ice Age”. Despite his best efforts, Grant could not make a living as a farmer and he and Dent agreed to sell off most of their farm equipment in late 1857.

Firewood Salesman (1854-1858)

Another profession Grant tried was that of a firewood salesman and delivery man. Ulysses felled oak and hickory trees on the 80-acre Hardscrabble farm, split the trunks, and packed chords for delivery in the city. He made a modest amount of money peddling his firewood but could not sustain his family on this income alone.

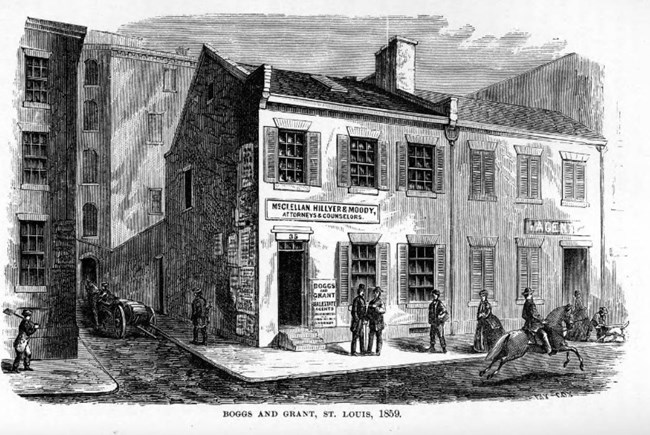

Boggs and Grant: Real-estate Agents (1859)

In 1859 Ulysses formed a partnership with Julia’s cousin Harry Boggs and the two opened a real-estate business in St. Louis City. Boggs managed the business, while Grant was responsible for collecting rent from their tenants. After Grant failed to successfully collect rent owed to the company on multiple occasions, he and Boggs decided to dissolve their partnership.

Ulysses Grant, County Engineer? (1859)

After the disbandment of Grant and Boggs Real Estate, Grant decided to apply for the position of St. Louis County Engineer. He had been trained in engineering and excelled in mathematics while at West Point, making him a good fit for the position. Charles F. Salomon, a German-born engineer who would later serve under Grant during the Civil War, also applied for the job. A three-person commission evaluated the credentails of both men and eventually chose Salomon for the position. "Rodney H. Wells, when he was later postmaster of St. Louis, would declare that Grant had waited on the courthouse steps for the result, and that when a friend emerged saying, 'You're beaten,' Grant had said, 'Yes, and by a Dutchman.'"[1]

On September 23, 1859, Grant wrote a letter to his father, Jesse from St. Louis informing him about his defeat for the county engineer position. He wrote, “I have waited for some time to write you the result of the action of the County Commissioners upon the appointment of a County Engineer. The question has at length been settled, and I am sorry to say, adversely to me. The two Democratic Commissioners voted for me and the freesoilers against me. What I shall now go at I have not determined but I hope something before a great while.” He reassures his antislavery freesoiler father, “you may judge from the result of the action of the County Commissioners that I am strongly identified with the Democratic party! Such is not the case. I never voted an out and out Democratic ticket in my life.” Nevertheless Grant, who admitted that he attended one meeting of the nativist Know Nothing party expressed his disdain over the result of the selection betraying some nativist sentiments, “The F[ree]S[oiler] party felt themselves bound to provide for one of their own party who was defeated for the office of County Engineer; a Dutchman who came to the West as an Assistant Surveyor upon the publick [sic] lands and who has held an office ever since.” He goes on to say, “there is I believe but one paying office held by an American unless you except the office of Sherif which is held by a Frenchman who speaks broken English but was born here.” [1]

Grant would later reflect in his memoirs looking back on this nativist outlook. “I have no apologies to make for having been one week a member of the American (Know-Nothing) party; for I still think native born citizens of the United States should have as much protection, as many privileges in their native country, as those who voluntarily select it for a home.”[2]

Grant at the U.S. Customs House (1859)

“Grant wrote home that his name had been forwarded for the appointment of superintendent of the custom house. ‘I am still unemployed,’ he said, ‘but expect to have a place in the custom house from the first of next month.’ He explained that if he was not appointed superintendent, he was to get a desk as a clerk in the custom house. He did receive the clerkship, but it lasted only about a month.”[3] Not long after this in May of 1860 Ulysses S. Grant and his family left St. Louis “removed to Galena, Illinois and took a clerkship in my father’s (leather goods) store.”[4] The beginning of the Civil War was less than a year away.

[1] Lloyd Lewis, Captain Sam Grant, 1950

[2] The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Volume 1: 1837-1861 pp 351-352.

[3] Personal Memoirs of US Grant (Dover Publications) p. 77.

[4] Walter Stevens, Grant in St. Louis, 1916

[5] Personal Memoirs of US. Grant (Dover Publications) p. 77.