Part of a series of articles titled Grand Canyon National Park Centennial Briefings.

Article

Grand Canyon National Park Centennial Briefings: Soundscapes

Centennial Briefings Purpose

When Congress established the National Park Service in 1916, Congress gave the agency a specific purpose: “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

During the summer of Grand Canyon National Park’s 2019 centennial, scientists and resource managers briefed fellow staff and the public about how they are helping to enable future generations to enjoy what is special about Grand Canyon.

This article is from a transcript of a July 9, 2019 briefing about sound monitoring in Grand Canyon. Its conversational quality reflects the passion and personalities of the people behind the park

July 9, 2019 Soundscapes Presenters

Hannah Chambless and Maggie Holahan spent the centennial summer as Geoscientists in the Park (GIP). The GIP program is a partnership between the National Park Service, Geological Society of America, Stewards Individual Placement Program, and AmeriCorps. It helps address the current needs and mission of our national parks while providing valuable work experience to participants in geoscience and other natural resource science fields.

Of her abiding interest in natural resources and public lands, Chambless says:

I have been interested in natural resource work ever since I was a kid in Girl Scouts and loved learning about earth science in school. When I graduated with my geology degree, I knew I wanted to work in public lands. I heard about the GIP program from a fellow graduate student back in Boston. I had always wanted to work for the park service, and it seemed like a great way to start. I landed the soundscape technician job at Grand Canyon, doing something new in a geologically incredible place!

The resources of natural sound and light are often forgotten but are no less important than other resources. When visitors are in the park, we want them to experience the setting in as close to its natural state as possible. Also, protecting natural sound and reducing noise is hugely beneficial to wildlife.

Of the role that sound has played in her experience of special places, Holahan says:

I first became aware of the effect humans have on natural soundscapes while on a research trip with the United States Geological Survey in the Glacier Peak Wilderness. We were deep in the backcountry, days of hiking away from major roads or towns, and yet there was a constant drone of high-altitude jets above our heads. It seemed as if despite all of the miles we had hiked, passes we had crossed, there was still no escape from the world of humans.

I graduated with a B.S. in geological sciences with a goal to gain research experience working for public lands. My GIP internship inspired me to combine my interest in volcanic hazards with my new experience in acoustics! I will be attending Boise State University for an M.S. in geoscience researching volcano acoustics using infrasound (low frequency sound). My main research project will use acoustic (infrasound) data to study geyser eruptions in Yellowstone National Park.

If you have ever stood on the canyon's rim at night, the lack of noise is quite captivating and can help put into perspective the vastness of the landscape in front of you. Equally as special are those layers of natural sounds that can create beautiful soundscapes in the park. Some of my favorites include a canyon wren's call cascading as it echoes across the canyon's walls, wind whistling through the trees, the deafening flow of water down a creek, the slow build and burst of coyotes howling, and the buzz of insects flying through the air.

2019 Soundscapes Presentation: Trying to Record Overflight Noise

There’s This Thing Called Substantial Restoration of Natural Quiet

Sound monitoring is a pretty new field. There’s a lot you can do with it. We’re trying to record overflight noise, primarily from commercial air tours over the canyon and high-altitude jets.

There’s this thing called substantial restoration of natural quiet that was outlined in the Overflights Act. A certain amount of the park has to be this level of quiet for this amount of time, i.e. 50% or more of the park must have no aircraft audible for 75 to 100% of the day, each and every day. It’s basically just seeing if we’re actually reaching that.

NPS/Damian Johns

The Flight Corridors are Over Backcountry Areas

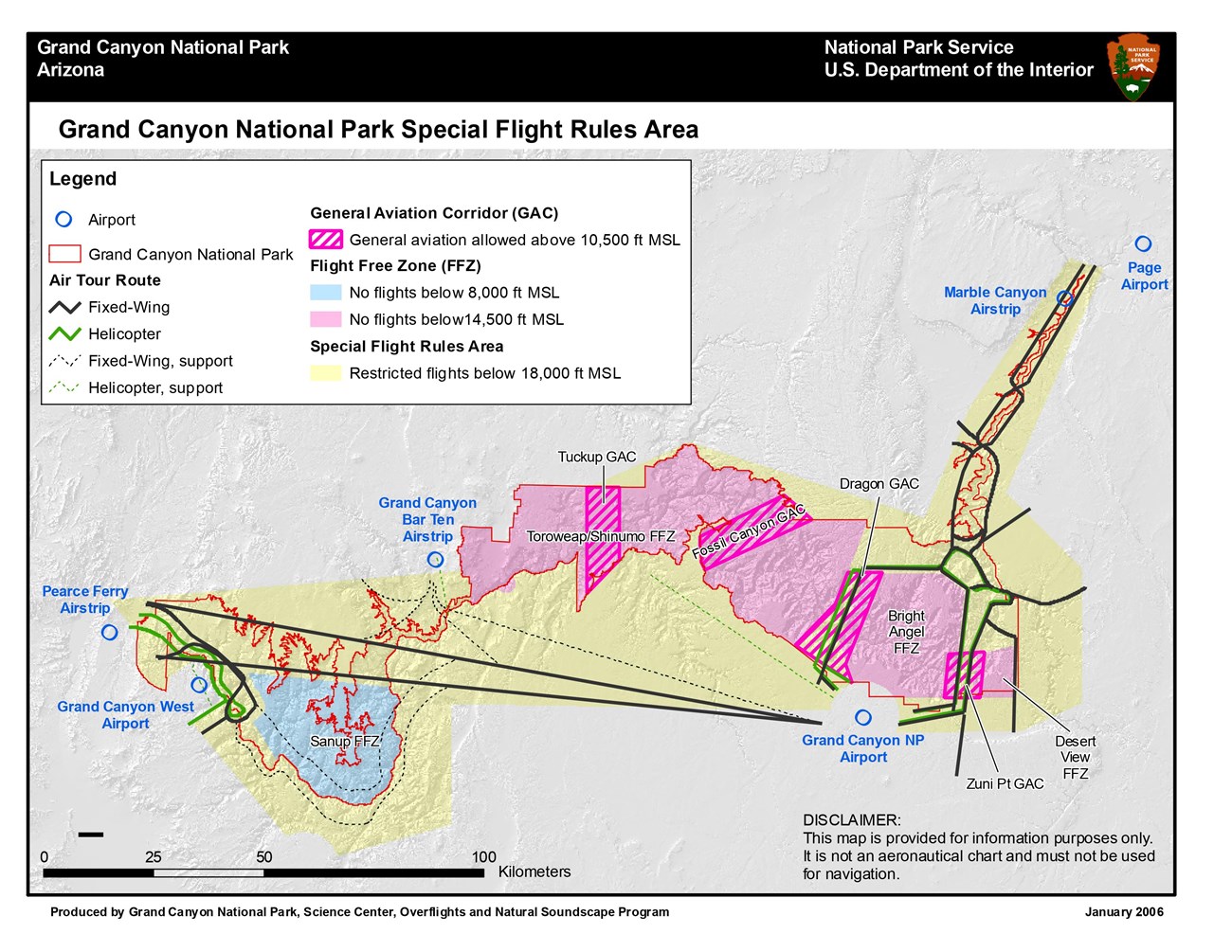

I think they made the flight corridors, areas within which commercial air tours are restricted, to reduce noise in the inner corridor, where the main trails are. The flight corridors are over backcountry areas, so people who are hiking in backcountry areas are hearing helicopter noise. There’s an area on the North Rim called The Basin where the flights will turn around, or go through a loop. We’re hoping to get a couple sites up at the North Rim in August. Then we’re hoping maybe to get some river upruns for Grand Canyon West, because there’s never been any kind of sound monitoring done out there.

We Get Median Sound Levels

You’re comparing one corridor that’s very high concentration of overflights and very loud to the entire park. It kind of dilutes that high amount of noise when you’re comparing it to that entire area. We do pick out the individual overflights, but the metrics that we calculate are all summaries. For example, we get median sound level for each hour.

They Model What the Noise Level Would Be

There are models that show how much of the park is exposed to a certain level of human-produced noise. The model just uses data from the FAA – the type of helicopters, other craft that they’re using, altitude data, topography, all that kind of stuff – and then they model what the noise level would be. What we’re doing is taking those measurements and validating what they have forecasted in that model.

I think another important thing to note is that the regulation for their minimum altitude over the rim is a voluntary agreement, so they’re not under any legal obligation to follow it.

We Have Sites in the Dragon Corridor, The Zuni Corridor, and Here

We have sites in the Dragon Corridor, the Zuni Corridor to the east, and here, just outside the Dragon Corridor. Those are the two main flight corridors. This site is to the east of the flight path, but our other site is almost directly underneath the helicopter and fixed-wing flight paths. The monitoring periods are winter and summer – low use and high use.

NPS

We’re Legally Required to Monitor the Soundscape

We’re legally required to monitor the soundscape under the 1987 Grand Canyon Overflights Act. And there was an air tour management plan that was put out in 2000 that requires this kind of data collection. We’re following the historic data collection. There are 71 historic sites that have collected sound data across the park. We had three sites out this winter, and now we’re starting our summer monitoring. We just added two new sites in the inner corridor. We were hoping to get some baseline data before the pipeline construction begins, because I think they’re adding about 5000 administrative helicopter flights for that.

They’re the People That Trained Us

There is a program at Colorado State University. They’re the people that trained us. They work really closely with the park service. They have a lot of undergraduate students in their lab analyzing the sound data. They’re called the Listening Lab.

It Was Great to Have All These People

We had a soundscape training from Randy, who is one of the directors of the Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division of the National Park Service, and this past month we were able to host another one that involved people from Zion, a GIP from Saguaro, and other biologists from Organ Pipe. It was great to have all these people who are trying to expand their soundscape monitoring and who have systems or are looking into borrowing some to come and be able to learn directly from the natural sounds people who trained us. I think we have probably the most set ups and staff focused on monitoring the soundscapes here. I think Zion is starting to look into that because they had a new airport or tour company come in recently. Organ Pipe gets military overflight noise, so the biologist that was here from Organ Pipe was interested in capturing that.

2019 Soundscapes Presentation: Capturing Human Noise

It’s Weighted For the Human Ear

This system is specifically aimed at capturing human noise. The frequency range that it can record is between 20 and 20,000 hertz, which is just the threshold of human hearing. This is a standardized system that’s used at other parks for soundscape studies that are intended to catch anthropogenic noise. It’s weighted for the human ear. We’ve heard cars a few times on the boundary road. We can hear car noise from our site in the Zuni corridor. We haven’t heard any human talking. Our site down the road, we’ve heard gunshots there in hunting season.

We Record Two Main Types of Data

We record two main types of data here. We get continuous audio data, and then we collect sound-wave data. So we have two different kinds of instruments collecting those. We have an audio recorder and then we have what’s called a sound level meter. Both of those instruments are hooked up to one microphone. Our battery box has two batteries in it, one for the audio recorder and one for the sound level meter. One of those batteries is constantly charged by the solar panel. We also have a line coming from the anemometer, which is giving us wind speed data, which allows us to see what days are really windy. Wind is loud, so it creates a lot of noise. The days that it’s really windy, we can’t use that data.

They’re Very Fragile

We’re limited by these set ups. This equipment case is completely custom made by one person. Every component, they’re very fragile. That’s our mic cable connector box. If it rattles too much, it will break. We get that from one person in Denver. Our audio recorder, too, it’s really old and not manufactured anymore, so the only way to get them is to buy them off of eBay. They’re really expensive now, because they’re rare. We had to buy our lithium battery from China. It took two months to get here, because it went by boat and then by ground.

NPS/Maggie Holahan

The Elk Here Are Pretty Active

We come out here every week to do site checks, mostly because the elk here are pretty active. Yesterday we came and our windscreen was on the ground – the microphone was exposed because an elk had come through and chewed on it. We think it licked it off. The elk chewed off or licked off the foam wind screen, knocked it on the ground, and then grabbed this cord, and lifted it up. It had it in its mouth and was, I think, trying to eat it, and was like, “wait, this isn’t food,” and then dropped it. It was pulling the battery case up, and it was like, “no, our cord!” You can actually see the elk signature in the spectrogram, which is just the visual representation of the soundwaves. We checked the game cam, and we were like, “yep, there’s the elk.” I still haven’t heard the recording where they’re chewing on it.

We’ve Caught a Lot of Different Animals

That’s why we set up a game camera here, because the first couple weeks that we set up the site back in the winter, we noticed that we would come to the site and things would be knocked over. With the game cam we’ve caught a lot of different animals – jackrabbits, a gray fox, mule deer, elk. In the winter we sprayed a rotten egg, natural elk, deer deterrent. It didn’t do anything. We’re debating putting up a fence down in our site that is in the corridor. Is the fence going to create more noise? We’ll see what we decide to do about that.

2019 Soundscapes Presentation: Processing Plots and Getting Numbers

We Have To Draw A Box on Every Single Event

The data analysis phase is a long phase. What we do is listen to eight days out of the monitoring period. We try to get a good spread of weekdays and weekends and days that we aren’t at the site, and then we have to listen to every single one of those days and pick out individually every single overflight, and basically draw a box on every single event. That takes a while.

We Just Started Analyzing That Data

We’re not finished with our winter data yet. We finished the site that’s down the road. We just started analyzing that data this week. We finished picking through and marking all the events, and now we’re actually processing plots and getting numbers.

It Could Be Used For Other Purposes

We have the data, and it could be used for other purposes. We’re trying to develop more interpretive resources by collecting natural sounds here at Grand Canyon. We learned from someone at Zion that he used his bat acoustic monitoring to determine what time of night was the best to do mist netting. We do get some great cicada sounds and bird calls, but it isn’t of that higher quality that you’d want for bioacoustics monitoring.

We do have two bioacoustics monitors down in the canyon right now. We’re trying to work on getting those continuously recording higher frequency sounds like birds and bats and other things to see what the bioacoustic baseline is.

In the early 2000s, they contracted out people to monitor the parking lots. At the visitor center, they had a car that literally had a mic pointing out of the back of the truck. It was just parked and recording. That was fascinating to listen to.

2019 Soundscapes Presentation: What We Do For A Site Visit

We can walk you through what we do for a site visit. Usually, we get here and then we’ll pause both of these recording instruments and get to work.

We’ll Check the Voltages on the Batteries

One of the first things we’ll do is make sure everything is plugged in and working, and then we’ll check the voltages on the batteries. 13.49 V. Is that good? That means that it’s getting charged by the solar panel, so that’s good. This one is about 3.28 V. This one isn’t getting charged at all by the solar panel, but it should last for about 30 days, usually the entire monitoring period. Usually if it gets down to 3.2 Vish, we’ll swap it out just in case, because it exponentially declines. We got four new ones last fall, so now we have seven, which is great. If it’s a newer one, it will last the entire time. If it’s an older one, we’ll swap it out halfway just to be careful.

We’ll Look at the Visual Spectrogram, the Sound Waves, and Then We’ll Also Listen to the Audio

Then we’ll move on to doing a calibration for our sound level meter. We check to make sure that the clocks on the sound level meter and the audio recorder haven’t drifted at all, because we want them to be as close as possible for when we analyze the data, because when we analyze the data we’ll look at the visual spectrogram, the sound waves, and then we’ll also listen to the audio at the same time, and that will help us pick out those overflight events. So we’ll just go to the clocks. If it’s more than two or three seconds off, we’ll fix it. It just helps us a lot to have both of those units the same time. If our audio’s a little bit off, it can make it hard to analyze. The audio recorder is about eight seconds off, so we’ll fix that.

That’s What We Use To Make Sure That Our Sound Level Meter is Picking Up the Right Decibel Level

And then we have our calibrators, which we’ll place on the microphone and they release a constant decibel tone. This one is 94 decibels at 100 hertz, and that’s what we use to make sure that our sound level meter is picking up the right decibel level. You can look on the screen to see what it’s reading. It’s at 93.9. That means we don’t have to calibrate it. So we’re done.

We’ll Download the Last Week’s Worth of Data

We check the site every week. We’ll plug the USB stick into the sound level meter and download the last week’s worth of data. When it downloads, it clears off the sound level meter. Recently we’ve been doing it a different way by putting this miniature USB stick into the sound level meter and it just stays in there. The sound level files will automatically be saved onto the USB stick, and we can leave it in there for the full 30 days if we want to without having to download the data every week, which takes ten to 15 minutes. Ten to 30! Yah, it can take a while.

It's Fun To Get Things To Work Again

The site visits can either go really well, really fast and streamlined, or you’re like, “ok, so this isn’t working. Why isn’t it working.” It’s kind of fun. It’s fun to get things to work again.

Last updated: May 5, 2025