Part of a series of articles titled Travel El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail: Essays .

Article

Global Perspectives on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro

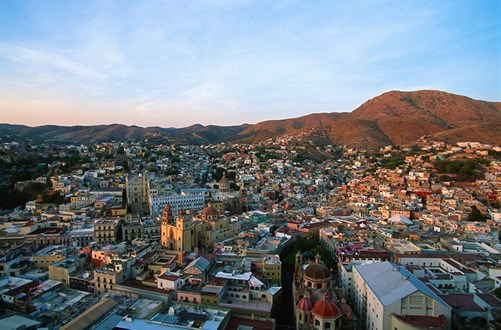

Photo © Jack Parsons.

On July 30, 1857, residents of the southern New Mexico town of Las Cruces woke to an unusual sight. Assembled on the central plaza was an odd kind of cavalry, a U.S. military corps comprised not of horses or mules, but of camels and dromedaries. The beasts of burden had been imported from Egypt and Turkey with a Congressional appropriation of $30,000. Their commission was part of a military experiment in which El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro played a central role.

The idea was to establish a military camel brigade in the dry American Southwest. In 1855, Congress paid to buy and ship the creatures to the Texas coast and overland to Camp Verde, outside of San Antonio. From there, Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for California and Nevada, led the hump-backed unit to El Paso, where he picked up the path of El Camino Real bound for the dreaded Jornada del Muerto (Journey of the Dead Man). Parched and perilous, the 90-mile desert crossing had led many humans and livestock to die of dehydration along the trail. It was the perfect place to put the camels to the test.

The camels and their crew plodded ably through the Jornada, then continued north along El Camino Real to Albuquerque, and west to Cubero and Zuni. They reached the Colorado River in January 1858. Despite the expedition’s success, however, the journey proved to be the only military use of camels in U.S. history. The brigade was disbanded, though escaped camels were spotted in New Mexico as late as 1902.

Today, the tale of the Egyptian-Turkish camel corps ranks more as military trivia than a major historical event. But the story’s international character adds another unique global dimension to the history and significance of El Camino Real. A congressionally designated National Historic Trail since 2000, and the longest cultural route in North America, El Camino Real’s importance in U.S. history and heritage is valid and verifiable. At the same time, the trail’s footprints transcend national boundaries, providing a path for exploring and recognizing the broader global perspectives of the trail.

Physically, the geography of the bi-national El Camino Real extends 1,200 miles through the Mexican interior and across 400 miles of West Texas and New Mexico. Culturally, the trail’s far-reaching international influences and impacts during 300 years of activity give it a distinguished place among the world’s great “cultural routes.” A designation increasingly being considered a critical aspect of world heritage, cultural routes are being promoted and protected on the world stage through efforts to build recognition and awareness of their valuable physical resources and cultural impacts.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) includes cultural routes among the four categories considered for its prestigious World Heritage List of places deemed to have “outstanding universal value.” In 2008, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), a non-governmental organization that advises UNESCO, adopted a “Charter on Cultural Routes,” which defines the pathways as prime candidates for heritage conservation. The charter calls on the world community to promote and protect cultural routes as shared international assets which contribute to world history and cultural diversity.

El Camino Real fits squarely into the definition of a cultural route as a physical path of travel, by land or sea, used over long periods of history. Adding to its value is the fact that El Camino Real not only served some of the world’s great civilizations during its history, but continues to influence global cultural heritage today. The trail is thus a thread in a uniquely interwoven web of world heritage that comprises other significant cultural heritage hubs—including northern Spain’s El Camino de Santiago, the intercontinental Silk Road, Qhapaq Ñan of South America, and the Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes of Japan’s Kii Mountain Range.

The Mexican section of El Camino Real is one of only a few cultural routes on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, recognized for its “outstanding universal value” in linking Europe and the Americas through the human interchange of language, cultural traditions and rituals, and objects of trade. More specifically, UNESCO singled out five existing urban World Heritage sites that represent El Camino Real’s significant cultural, commercial, spiritual and geographical impacts. It also noted 55 sites—bridges, chapels, former haciendas and convents, natural landmarks and more—related to the use of the road. But while such historic sites and structures are physical bookmarks in the story of El Camino Real, they don’t tell the whole story.

Central to UNESCO’s consideration of a cultural route is the cultural landscape through which it passes. Like a pearl necklace connected by a sometimes fragile thread, the historic pearls that draw visitors to cultural routes often are connected by fragile roads and landscapes. Without the connectivity of the greater cultural landscape, the individual sites and symbols highlighted as prime destinations along cultural routes would be incomplete, their stories less than whole. A cultural route is therefore always greater than the sum of its parts.

For this reason, both UNESCO and ICOMOS extend the definition of cultural routes beyond their physical character as paths of communication or transportation. As conduits of human movement and cross-ethnic connection, both historically and today, cultural routes inspire a fusion of cultures and interchange of human values that significantly impact world heritage and play an ongoing role in daily life and culture. In this expanded view, the values and cultural touchstones that the routes transmit—from the development of a spirit of place, to the transmission of religious belief systems, to the adoption of language, art, music, architecture, science, technology, and secular rituals and traditions—are as important as the routes themselves.

A World of Notable Cultural Routes

As a historic trade route and a contemporary cultural route, El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro connects backward and forward in time to other routes that shaped the world’s diverse cultural heritage. The Inca Road, for example, has been added to the World Heritage List. More appropriately known by its historic name as Qhapaq Ñan, or as the Main Andean Road, this prestigious pathway traversed the highest peaks of the Andes and portions of the Pacific Coast to connect the pre-Colombian empire of South America.

Linking the common cultural heritage of what today is Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, Qhapaq Ñan was the political, economic and organizational backbone of the Inca Empire, which was in power when the Spaniards arrived in the 16th century. Much of the road was constructed some 2,000 years before the Inca, but ultimately, its 14,000-mile span supported the empire’s administrative, production and ceremonial network of commerce, industry and worship. The road’s centuries-long survival and ongoing use remain symbols of the Andean peoples’ harmonious adaptation and relation to one of the harshest geographical settings in the Americas.

Qhapaq Ñan is an extraordinary example of the intangible spirit of a place and its peoples that defines many cultural routes. Such spirit was critical to the formation of pilgrimage routes, or pathways of devotional travel, whose constructed sites and natural landscapes are considered sacred to the pilgrims who journey there.

The pilgrimage route of El Camino de Santiago is inscribed as a cultural route on the World Heritage List. Moving across the Spanish-French border, the route features 1,800 historic settlements, religious and secular buildings, and engineering structures representing a centuries-long evolution of European art, architecture and spiritual life. In the Middle Ages, El Camino de Santiago played a fundamental role in the cultural exchanges of different social classes of the Iberian peninsula and greater Europe. Today, the countless thousands of religious and secular pilgrims who come there continue to demonstrate how the power of faith and the experience of the physical environment shape a spirit of culture and place.

Devotion to nature and the environment also gave rise to other major cultural routes. In Australia, for example, where animist beliefs rely on the common rhythms of the land to navigate vast distances, aboriginal cultural routes developed in relation to the availability of water and other natural resources. Song lines, or dreaming tracks, provide information describing the location of landmarks, waterholes and other natural phenomena. Expressed in different languages across distant landscapes, this unique way-finding tradition links diverse indigenous peoples with different customs and serves as a means of communicating ancient aboriginal knowledge.

Similarly, a more than 1,200-year tradition of nature worship, based on Shinto and Buddhist belief systems, is at the heart of the World Heritage Shrines and Pilgrimage Routes of Japan’s Kii Mountain Range. These pilgrimage routes wind through the dense Kii Mountain forest to three sacred sites—Yoshino and Omine, Kumano Sanzan and Koyasan—and the capital cities of Nara and Kyoto. Shrines, some dating as early as the 9th century, are highlighted at each of the three sites, while the surrounding forest landscape hosts abundant streams, rivers and waterfalls. This striking sacred environment and its persistent tradition of nature worship not only influence the living cultures of Japan, but draw some 15 million annual visitors who hike the cultural route for ritual and secular purposes.

As routes that were developed to tie diverse regions, empires and peoples together, cultural routes are geographically, historically and culturally complex. While the most prevalent means of passage was by land, cultural routes also combined land- and sea-based transportation to connect far-flung cultures and communities. For example, the Silk Road, also called the Silk Route, stretched from east to west by land and sea across a quarter of the globe. Its intercontinental system of maritime and terrestrial routes spread from China to the Mediterranean Sea, linking Asian and European peoples across 4,000 miles, 25 countries and 20 spoken languages.

Named for its most famous trade good, The Silk Road was the first channel of trade between the ancient empires of China, Central and Western Asia, the Indian sub-continent and Rome. In addition to transmitting material goods, the route gave rise to an unprecedented peaceful exchange of cross-cultural knowledge, beliefs, ideas, customs and traditions between East and West. These exchanges over 3,000 years profoundly shaped and enriched the contemporary heritage of the various cultures that inhabit the Silk Road today.

El Camino Real Intercontinental

Like the Silk Road, El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro is a classic example of a trade route that combined terrestrial and maritime transport to touch many cultures around the globe. The trail’s 1,600-mile span in the Americas linked to an intercontinental network of roads and sea routes that enabled the cultural and economic coalescing of indigenous peoples of the Americas with multi-ethnic Europeans, Africans, Indians and others. For this reason, some scholars refer to the trail as El Camino Real Intercontinental.

Speaking at an April 2006 international colloquium on El Camino Real, Gustavo F. Araoz of the U.S. committee of ICOMOS said, “The intercontinental Camino Real was the first successful global network intentionally established on the principles of economic interdependence among many world regions….the Camino Real’s full significance [could] not be understood outside the context of its full global network of economic interdependence and cultural exchange over several centuries.” As an example, Araoz noted El Camino Real’s earliest development in linking the silver mines of Zacatecas, Mexico, with the mercury mines of Almadén, Spain.

Spain’s ability to connect such far-reaching local and global landscapes is rooted in its unique history of caminos reales, or royal roads. Various caminos radiated from Madrid, including a 16th century route connecting Madrid to Gijón and Leon. With the Spanish colonization of the Americas, a network of caminos was developed from Mexico to Peru, Paraguay, Colombia and beyond. Among these were pre-European roads that remained in use after the arrival of the Spaniards. A main section of the Inca Road between Quito and Mendoza in the Peruvian Andes was considered a royal road. The pre-Hispanic trail that followed the Rio Grande north through New Mexico, and which had linked the region’s pueblos and tribes to Mexican tribes and trading centers since at least the 13th century, also became part of the camino real system.

In Mexico, the overland section of El Camino Real featured four major caminos designed to converge and diverge from the viceroyal capital of Mexico City. The earliest road connected from the east coast at Veracruz to Mexico City, while another moved there from Acapulco on the west coast. A third camino went south from Mexico City through the large and ethnically diverse lands of Oaxaca to Guatemala. The fourth ambitious camino, originally known as El Camino de Plata (The Silver Road), moved silver from Zacatecas and other area mines to the capital. With the 1598 colonization of New Mexico, the route was extended as El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the main transportation route connecting Mexico City to the interior lands of northern New Spain.

Designation as a camino real was more broadly understood to encompass maritime routes. For example, a prominent 16th- and 17th-century route through the Isthmus of Panama, El Camino de Cruces, linked overland Panama to its Atlantic port of Portobelo. Spanish galleons and merchant ships arrived at Portobelo with stocks of European goods, then turned back to Spain with coffers of South American gold and silver.

Maritime routes also connected Mexico’s overland routes to Spanish colonies in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as to Europe and the Far East. Mexico City’s camino to the port of Veracruz, on the Gulf of Mexico, was established to support the European trade via a maritime route to Cádiz and Seville. Likewise, the capital’s camino to Acapulco, on the Mexican Pacific coast, supported the Asian Trade as the port through which the fabled Manila Galleons departed and arrived from the Philippines.

Commercially, the caminos allowed for increased exports of ore to Spain, the coining of large amounts of currency, and massive stocks of trade goods bought and sold. This in turn generated unprecedented growth in international trade. Spain, which enforced major restrictions along El Camino Real, was a major monetary beneficiary in the new world economy. But in time, even such far-flung Spanish colonies as New Mexico benefited from the intercontinental flow of goods. Traveling in New Spain in 1803-04, Prussian geographer, naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt noted the major commercial importance of Mexico’s camino network, mentioning El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro among the region’s local routes with global import.

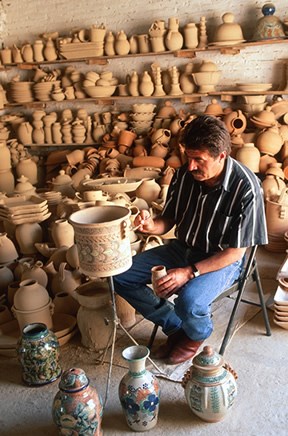

Indeed, New Mexicans who lived along El Camino Real’s local roadways were afforded access to such European luxury goods as wine, chocolate, olives and nuts. Prized Asian goods, including porcelain, silk and spices, also moved up the trail. The 1762 will of a prominent Santa Fe resident, Juana Lujan, lists items imported from France and China. The 1815 will and estate inventory of another leading Santa Fe resident, Captain Manuel Delgado, included imported Mexican textiles and ceramics and Chinese porcelain among his personal items. Delgado’s thirteen velvet, cashmere and silk suits had either been imported from Mexico, ready-to-wear, or were made from imported Mexican, Spanish or Asian cloth.

On the downside, El Camino Real carried a host of European diseases into New Mexico. Smallpox, measles, cholera and respiratory ills were unknown to local indigenous peoples before the establishment of El Camino Real. By the 17th century, the diseases had contributed to a steep decline in the population of New Mexico’s Pueblo peoples.

By the 19th century, the cultural impacts of El Camino Real were deeply ingrained in the local history and heritage of indigenous and immigrant New Mexicans alike. From linguistic and religious influences, to traditions and techniques in art, architecture, music and literature, the cultural touchstones of Europe and Mexico became part of the cultural identity of New Mexicans. These influences broadened with Mexican independence from Spain in 1821.

The opening of the Santa Fe Trail from Missouri to Santa Fe, and the Old Spanish Trail from Santa Fe to the seaports of California, extended the reach of El Camino Real and brought new cultural forces flowing into New Mexico from the eastern and western U.S. These links further expanded intercontinental trade on El Camino Real as U.S. goods were moved to such previously inaccessible destinations as Mexico, Europe, Manila, Cuba and the Caribbean.

Community Protection of Cultural Routes

With the arrival of the railroad in 1880, El Camino Real was abandoned as the avenue for long distance transport. Although the trail’s intercontinental pathways served and indelibly shaped the cultural heritage of Mexico, New Mexico and West Texas, its international legacy faded into the ebb and flow of the trail dust and sea tides it followed. The recent emphasis on cultural routes by UNESCO, ICOMOS and others, however, is leading numerous countries and organizations to develop systems for their documentation and preservation.

In 2000, when the U.S. Congress designated the 400-mile U.S. portion of El Camino Real in New Mexico and West Texas as a National Historic Trail, it encouraged collaboration between the U.S. and Mexican governments to enhance El Camino Real’s valuable historical and cultural assets on both sides of the border. Today, the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management, which jointly administer the U.S. portion of the trail, partner with the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and other Mexican entities to create best practices for trail protection, provide technical assistance, and develop complementary preservation and education programs that increase public awareness.

Cultural heritage tourism is also being explored as an educational and economic development tool that encourages visitors to experience the trail’s unique sites and stories. The appropriate use of cultural heritage tourism will further El Camino Real’s legacy of cross-cultural exchange and celebrate the common history and heritage of the trail in Mexico, the U.S. and internationally.

Globally, study and identification of international cultural routes is well underway. But there is still a long way to go to ensure their long-term protection and preservation for future generations. Cultural heritage proponents are putting their faith in the public. Ultimately, personal pride in, and identification with, the cultural riches and contemporary relevance of the routes are the best tools for their protection.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.

Last updated: July 12, 2020