Last updated: August 15, 2025

Article

General Washington in the Native Northeast

By Dr. Benjamin Pokross, Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

It had been ten days since the Caughnawaga Mohawk men had arrived at the camp in Cambridge with their wives and families, and George Washington was still not sure what he was going to do. This was the second time that one of their leaders, Atiatoharongwen (also known as Col. Louis Cook), had come to Cambridge, and he had again made it known that he could raise four or five hundred men to fight for the colonists if he was given a commission in the Continental Army. But Washington was unsure how he would pay for all these additional soldiers if Atiatoharongwen did what he said, and even more apprehensive about the idea of engaging Indigenous allies at all.1 At least it had stopped snowing on the clear, cold, morning of January 31, 1776; this was the day Washington had promised to meet the Mohawk delegation outside.2

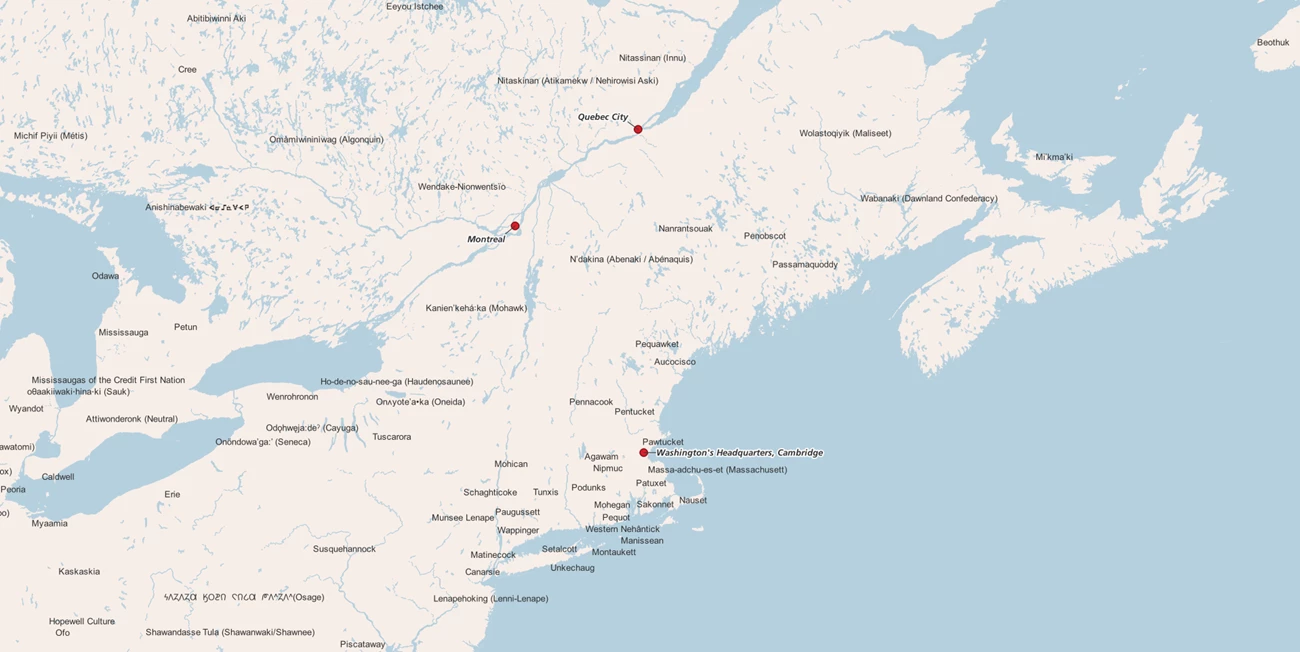

Washington’s “Out-Door’s Talk”, as he called the subsequent conversation in a letter to General Phillip Schuyler, would be the most extensive of several interactions with Indigenous people he had had while he lived in the Vassall House.3 These visits did not result in decisive alliances or enduring treaties. They matter, however, for two reasons. The first is that they emphasize how the Revolution—normally thought of as a conflict between American colonists and the British—occurred on Native land, in areas that had long been stewarded by Indigenous communities and where Native people continued to find ways to survive in spite of colonial upheaval. Secondly, these visits highlight the unsettled and transitional character of the very early days of the Revolution. For both Washington and the Native diplomats who came to visit him, this was a moment of experimentation, of exploring what a possible relationship between the Continental Army and Indigenous Nations could look like.

Map data provided by Native Land Digital (https://native-land.ca/). Used with permission for educational and non-commercial purposes.

George Washington’s outlook had long been shaped by Native people and an interest in Native land. His first job as a teenager was as a surveyor in the Virginia backcountry, and he acquired Western land throughout his life, ending up owning almost 45,000 acres of land in what is now Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. In his early military career, he fought with and against Native people, particularly during two unsuccessful expeditions in the Ohio Country in 1753 and 1754 at the very beginning of the French and Indian War.4

When he assumed command of the Continental Army in Cambridge on July 3, 1775, Washington was therefore well aware of what it could mean to have Indigenous nations as both allies and enemies. At that time, he was especially concerned about the potential role that Native nations on the northern border of the thirteen colonies might play in the growing conflict. Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland, all then controlled by the British, were the subject of much anxiety and hope for the colonists—could these Northern colonies be encouraged to join the revolutionaries? Or would they be a threat?5 That summer, the Continental Congress ordered an attack on the British stronghold of Montreal, and Washington himself deputized Benedict Arnold to lead an assault from Cambridge to Quebec City later that fall.6 These offensives made the many Indigenous communities who lived in Canada increasingly valuable as allies, and the British and the Americans alike began to consider aligning with Northeastern Native nations. On both sides, however, there was a general apprehension at engaging Indigenous allies, from concerns over expense as well as from prejudiced fears that Native people were particularly violent and uncontrollable.7

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

With all these competing ideas weighing on him, Washington was unsure of how to react when, just a few weeks after he took command, a series of Indigenous diplomats began to arrive in Cambridge pledging their support to the colonists. Atiatoharongwen came on August 3, 1775, months before his January visit, accompanied only by Col. Jacob Baley.8 A group of Abenaki men, led by a chief named Swashan, arrived several weeks later and stayed throughout the Siege of Boston.9 At the end of September, Skenandoah, a military leader of the Oneida Nation in Western New York, arrived in the camp with Reverend Samuel Kirkland, a longtime missionary to the Six Nations (also known as the Haudenosaunee Confederacy).

In general, Washington was respectful towards these Indigenous diplomats, open to their help but holding back from formally allying with any of them. He told the Continental Congress, for example, that as Skenandoah’s “tribe has been very friendly to the United Colonies and his Report to his Nation, at his Return, have important Consequences to the public Interest, I have studiosly endeavour’d to make his Visit agreeable.”10

Washington took a similar approach with the Caughnawaga delegation in January, going even further to earn his visitors’ trust and engage on their terms. The Mohawk men were taken to see the fortifications built in East Cambridge and dined with Washington, his wife, and John Adams, who was passing through Cambridge. At the “Out-Doors Talk,” Washington met with the Caughnawaga in the open air, as they had requested, and, when they presented him with a copy of the Treaty of Albany they had recently signed with General Phillip Schuyler in Western New York, he added his own signature.11 “We are very glad a firm peace is now made between us and our brothers,” Ogaghragighte (also known as Jean Baptiste), a Caughnawaga chief, said in response. He went on to request that Washington “give us a letter to General Schuyler, and inform him that if men to call upon us, and we will join him.”12

However, the Caughnawaga did not receive this letter. As had been his policy, Washington made no promises at the end of their meeting, assuring them that he would write to Schuyler to inform the general of what had happened. In his letter to Schuyler, Washington eschewed responsibility for engaging with their new allies. “The Expediency of calling upon them I shall leave to you,” he wrote, “Circumstances and policy will suggest the Occasion.”13 While he treated these Indigenous diplomats with respect, Washington ultimately did not commit himself or the Continental Army to any obligations towards the Caughnawaga.

Washington followed up this meeting with two, now-lost letters to Indigenous communities in Maine, but this was the extent of the Indigenous diplomacy that he conducted from Cambridge. These tentative steps had a variety of outcomes.

Yale University Art Gallery

Atiatoharongwen, who was of both Native and African descent, went on to become a Lieutenant Colonel and was the highest ranking Black and Indigenous officer in the Continental Army. Yet the Caughnawaga Mohawk Nation eventually sided with the British.14 Skenandoah and the Oneida were very important allies for the colonists during the war. Yet, like many Indigenous communities, the Oneida suffered greatly over the course of the conflict, with many men dying and intense disruptions to traditional ways of life. The Oneida received compensation for damage to their homes and property in 1794, but by this time they had already lost most of their land through a series of treaties with New York state.15

Washington, of course, would go to lead the Continental Army to victory and become the first President of the United States, where he would help establish the federal government’s interest in aggressive Westward expansion and the expulsion of Native people from their lands. Treaties and other forms of diplomacy would become key to the new nation’s insatiable desire for Indigenous territory. Focusing on Washington’s time in Cambridge reveals the possibility, however, of a different kind of relationship between the nascent United States and Native nations. Washington was no great advocate for Native sovereignty, and the Indigenous leaders he met cared primarily about defending their own homelands. But, in the confusing first few months of the Revolutionary War, there was the possibility of alliance between equals, an interest from both Washington and his Native counterparts in exploring a relationship centered on mutual respect and accommodation.

Notes

- George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, vol. III (1775-1776), (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1889), 377-378.

- Moses Sleeper, Diary, 10 June 1775 - 7 September 1776, Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National History Site, LONG 36353.

- Washington, The Writings of George Washington, vol. III, 378.

- Colin G. Calloway, The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, The First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation. (Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Jeffers Lennox, North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution (Yale University Press, 2022), 18-20.

- J.L. Bell, “Diplomacy and Invasion” in “George Washington’s Headquarters and Home, Cambridge, Massachusetts” (National Park Service, 2012), 495-527.

- Calloway, Indian World of George Washington, 218.

- On this occasion, Atiatoharongwen represented himself as speaking on behalf of the Caughnawaga. Contemporary scholars, however, doubt whether he had that authority. Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country, 69.

- George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 2, 16 September 1775 – 31 December 1775, ed. Philander D. Chase, (University Press of Virginia, 1987), 61.

- Bell, “George Washington’s Headquarters,” 518.

- George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 3, 1 January 1776 – 31 March 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988), 223–224.

- George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 3, 1 January 1776 – 31 March 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. (University Press of Virginia, 1988), 240.

- Darren Bonaparte, “Colonel Louis Cook,” Wampum Chronicles, accessed September 2, 2020, https://www.wampumchronicles.com/toomanychiefs6.html.

- For more on the Oneida experience during and after the Revolution, see Joseph T. Glatthaar and James Kirby Martin, Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians and the American Revolution (Hill and Wang, 2006).