Last updated: January 14, 2021

Article

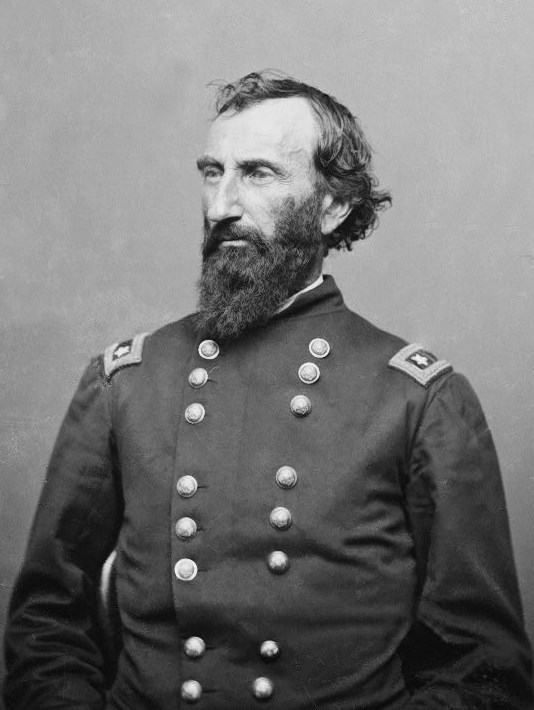

General John A. McClernand: General Grant's Work Nemesis

Library of Congress

Have you ever had a job in which you had to work with someone you did not really care for very much? Even General Ulysses S. Grant had coworkers he did not get along with very well. General John McClernand of Illinois was perhaps the person General Grant disliked the most during the American Civil War. For much of the first two years of the war, McClernand was a pain in Grant’s neck.

John McClernand was born in Kentucky, but moved to southern Illinois as a small boy with his family. McClernand’s father died shortly after the family arrived in Shawneetown, Illinois, so he was raised by his mother who made sure he received good education. McClernand studied law and soon became involved with the Democratic Party in Illinois. One of his main political rivals was a young politician by the name of Abraham Lincoln. Even though McClernand and Lincoln were on opposite sides of the political divide, the two remained good friends. This friendship lead to McClernand later being appointed as a general early in the Civil War while Lincoln was President of the United States. Lincoln wanted McClernand, who was a popular U.S. congressman at the time, to serve as general because he wanted to motivate residents in southern Illinois to fight for the Union cause.

Another person living in Illinois was also appointed general around the same time as McClernand, and that person happened to be Ulysses S. Grant. Aware of McClearnand’s popularity, Grant asked McClernand to give a pro-Union speech to the soldiers in his 21st Illinois regiment in June 1861. At first, the two seemed to work well, but over time the relationship between Grant and McClernand gradually deteriorated.

The working relationship began to sour shortly after General Grant’s first major battle of the war at Belmont, Missouri on November 7, 1861. Grant’s forces drove the Confederates back through their camp along the Mississippi River in what seemed like a total victory, but many of McClernand’s men lost their military discipline and began to loot the camp while McClernand gave a victory speech. The Confederates were able to counterattack, and they drove the Unionists back to their transport ships in which they narrowly escaped. In the end, the victory ended up seeming more like a defeat. To make matters worse, McClernand tried to lecture General Grant on strategy after the battle. It took Grant, a veteran of the Mexican-American war, a great deal of self-control to keep from losing his temper against the politician who had little experience in battle.

At Fort Donelson in February 1862, General McClernand ordered an ill-advised charge without consulting General Grant first. Grant further questioned McClernand’s ability as an officer. McClernand also wrote an order congratulating his men on their victory and implied that he and his men had carried the greatest burden in the battle. General Grant took exception to McClernand’s downplaying the important role other officers and regiments played in the battle.

General McClernand performed better at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. McClernand and his men helped General William T. Sherman slow the Confederate surprise attack on the morning of April 6th. This effort gave General Grant enough time to set up a strong defensive line near Pittsburg Landing. General Sherman gave McClernand credit for his performance that day, but Grant did not. McClernand believed he had been disrespected by Grant, so he wrote to President Lincoln to boast about himself and his soldiers.

In the fall of 1862, General McClernand traveled to Washington, DC to talk with Lincoln about commanding his own army. McClernand made this request without consulting General Grant or General Henry Halleck, the department commander. Nevertheless, he was able to get President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to agree to the plan. Lincoln and Stanton did not consult Grant, or Halleck, about the plan either. General McClernand was able to raise several regiments in Illinois, and he assumed that he would be in command of an army that would be moving on Vicksburg soon. When Grant realized what McClernand was up to, he convinced General Sherman that they should move on Vicksburg themselves before McClernand arrived in Tennessee to take command. Grant did not believe that a campaign of such importance should be left in the hands of someone as incompetent as McClernand. When McClernand arrived to find that his army was gone, he immediately went to General Sherman’s headquarters to declare himself commander. When Grant complained to General Halleck about the situation, a compromise had to be made. General McClernand’s soldiers would be added as a fourth corps of the army, and he would lead the advance towards Vicksburg. Grant, however, would still be overall commander of the expedition. Neither general was happy about the compromise.

The bitterness only grew larger during the Vicksburg Campaign. General McClernand continued to give himself, and his soldiers, credit for the victories that the Unionists achieved during the campaign. He frequently criticized General Grant behind his back, often telling people that Grant was a drunk. General Grant knew of the criticisms being spread around by McClernand, but he tolerated it because he knew how popular McClernand was politically. Grant’s patience was wearing thin, however.

Once General Grant surrounded Vicksburg in May 1863, he made two attempts to break through the Confederate trenches surrounding the town. During the attack of May 22nd, General McClernand was able to lead his men into the Railroad Redoubt, which guarded the main tracks leading into Vicksburg. McClernand sent a dispatch to Grant requesting reinforcements, but Grant was reluctant at first because he believed that McClernand was exaggerating just how successful the breech had been. General Sherman convinced Grant to send more soldiers, but the reinforcements were not able to help McClernand stop a Confederate counterattack. General Grant was not pleased with McClernand after the battle because he believed that the call for reinforcements only resulted in more men being killed and wounded.

McClernand was extremely upset when General Grant criticized General McClernand in his battle report for the attack of May 22nd. Other officers said that McClernand performed well that day, but Grant was not convinced. At this point, the bitterness McClernand felt towards Grant grew stronger. In June 1863, General Grant sent orders to McClernand telling him to send troops to help protect the rear of the army, which caused McClernand to fly off into a cursing rage. Colonel James Wilson, who had delivered the orders, thought McClernand was cursing him. Wilson stated that he was ready to fight McClernand with his fists. McClernand had to explain that he was not cursing Wilson, and he told Wilson that he was just “…expressing his intense vehemence.” It became a running joke when someone would curse that, “He’s just expressing his intense vehemence.”

Once again, General McClernand decided to write an order congratulating himself and his soldiers for carrying the main burden for the Unionists during the Vicksburg Campaign, but this time the order was published by the press, a violation of War Department rules and regulations. No order was to be placed in the newspapers unless it had been approved by the War Department. General Grant took this opportunity to rid himself of his work nemesis, and he relieved McClernand of his command. McClernand tried to blame his adjutant for the order being published in the papers, and he tried to convince President Lincoln that he was not to blame. McClernand even tried to take his case to the general public, but it did no good. General McClernand’s expulsion was upheld.

Eventually, General McClernand was brought back to serve in General Nathaniel Banks’ armies, which were fighting in the Trans-Mississippi area of the war. McClernand spent much of his time inspecting fortifications along the Rio Grande. He finally decided to resign in November 1864, believing he could do more for the war effort as a civilian. McClernand lived to the ripe age of 88, passing away in 1900. He remained bitter for much of the rest of his life over his demotion during the Vicksburg Campaign.

Jones, Wilmer L. Volume One: Generals in Blue and Gray. Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA, 2004.