Last updated: May 26, 2021

Article

General Grant Gives General Lee "The Slip" At Petersburg

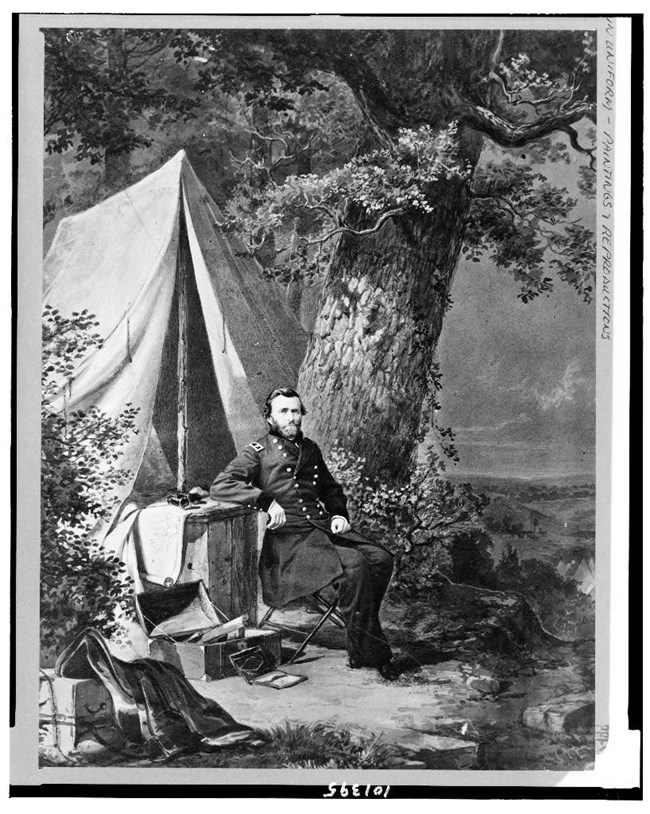

A. Berger/Library of Congress

That summer, Grant felt pressure not only militarily, but politically. 1864 was a presidential election year and with the constant battles and casualties, war weariness among the Northern population was setting in. Within the Democratic party there was a vocal faction known as the Peace Democrats who favored ending the war at all costs, even if it meant negotiating with the Confederacy based on granting Confederate independence. For other Northerners, however, the Peace Democrats’ platform was against everything that countless Union soldiers had fought and died for, let alone the implications to the millions of African Americans whose very freedom from slavery was on the line.

With so much at stake and longing to bring the war to a close, General Grant showed his adaptability in his next move. He later reflected in his memoirs, "Lee's position was now so near Richmond and the intervening swamps of the Chickahominy [River] so great an obstacle...that I determined to make any next left flank move carry the Army of the Potomac south of the James River." After the setback at Cold Harbor, Grant wrote to General Halleck on June 5 expressing his frustration of the present situation and outlined his new plan. "The enemy deems it of the first importance to run no risks with the armies they now have. They act purely on the defensive behind breastworks, or feebly on the offensive immediately in front of them . . .Without a greater sacrifice of human life than I am willing to make all cannot be accomplished that I had designed outside of the city." Grant's hope in maneuvering south of the James River was to attempt yet again to force Lee's army away from their trenches to fight in the open. Another option came to the forefront, however. Petersburg, a city some 20 miles south of Richmond, possessed vital railroads and wagon roads that served as Richmond's (and Lee's army) main artery of supply to the South and West.

This plan was not without its risks, and Grant outlined them in his memoirs. One big problem was coordinating movements. Grant had to oversee all his subordinates, other military actions in Virginia in the Shenandoah Valley, and General Philip Sheridan with a force west from the Richmond area to wreck the Virginia Central Railroad. In total, Grant had to coordinate the movements of some 115,000 men within his immediate vicinity. The next obstacle was getting the majority of these 115,000 men across two rivers, the Chickahominy and the James. This movement required the use of all available watercraft as ferries. According to historian James McPherson "Union engineers built perhaps the longest pontoon bridge in military history, 2100 feet, anchored to hold against strong tidal currents and a four-foot tidal rise and fall” across the James. Finally, Grant had to worry about the enemy. The Confederates operated on interior lines of communication and travel. Grant noted that they knew the countryside better and could rely on information provided to them by a friendly population. Grant worried that Lee’s forces could attack his armies during a vulnerable move across the James River. There were also known Confederate gunboats lurking somewhere along the river.

Despite these complications, Grant's movement beginning on June 12 were a tremendous success. McPherson writes that "so smoothly was [Grant’s] operation carried out, with feints toward Richmond to confuse Lee, that the Confederate commander remained puzzled for several days about Grant's intentions." It was these several days in which the future of the war hung in the balance. Upon crossing the James, Grant's lead elements closed in on the city of Petersburg. On June 15, Grant later estimated in his memoirs that the enemy confronting him at Petersburg numbered only 2,500 men along with some irregular forces. Lee's main army did not arrive until three crucial days later on the 18th.

Considering this tremendous success of moving his army south of the James River, everything seemed to go wrong from there. The coordination which was so effective in crossing two major rivers now fell apart. Union forces attacked Petersburg too cautiously. Many were veterans of Cold Harbor weeks earlier and remembered the horrors of attacking well fortified confederate trenches. This "Cold Harbor Syndrome" may have accounted for the hesitation and confusion among commanders and soldiers. Although the Union did gain some of the Confederate trenches in some hard and desperate fighting, a stalemate emerged as Grant’s forces failed to capture Petersburg. The arrival of Lee's army to reinforce General P.G.T. Beauregard when they recovered from Grant's slip on June 18 began a siege of Petersburg that lasted over nine months. Although Lincoln was reelected and Grant eventually prevailed over Lee, Grant later reflected on his frustration in his memoirs. "Petersburg itself could have been carried without mush loss...This would have given us control of both the Weldon and South Side Railroads...and would have given us greatly the advantage in the long siege which ensued."

Grant Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co., 1885. Da Capo Press. 2001. Pgs. 446-458.

McPherson James. Battle Cry of Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press 1988. Pgs. 734-743

Simon, John Y. ed. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Volume 11: June 1-August 15, 1864. Carbondale Il, Southern Illinois University Press. 1984. Pgs. 19.

McPherson James. Battle Cry of Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press 1988. Pgs. 734-743

Simon, John Y. ed. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Volume 11: June 1-August 15, 1864. Carbondale Il, Southern Illinois University Press. 1984. Pgs. 19.