Last updated: January 14, 2021

Article

General Grant and the Fight to Remove Emperor Maximilian from Mexico

Wikipedia

Ulysses S. Grant’s longstanding interest in Mexican affairs dated back to his service in the Mexican American War from 1846-48. During this time, Grant observed the culture and customs of Mexican society and admired its beautiful natural landscape while serving with the U.S. Army. During the American Civil War thirteen years later, Mexico found itself in a new fight for independence against France. After Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia in April 1865, General Grant turned his focus to Mexican affairs.

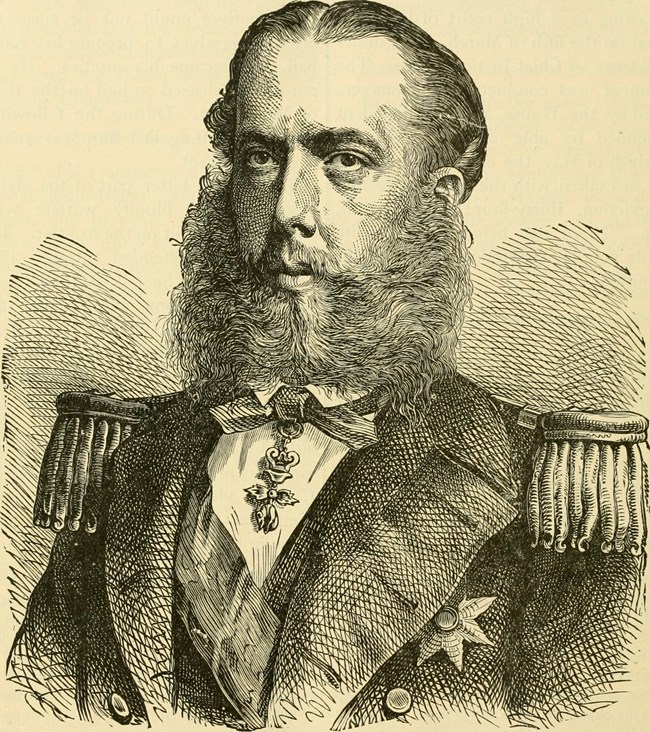

In the decades following its independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico’s government faced a great deal of political instability and growing debts. These financial obligations became overwhelming, and the government stopped paying its debts to various European nations, including France, by the time the American Civil War broke out in 1861. French Emperor Napoleon III took advantage of the situation by attempting to create a French empire in Mexico. French troops mobilized for deployment to Mexico. During one French invasion on May 5, 1862, Mexican resistance fighters defeated the French at the Battle of Puebla, which is the inspiration for the popular Cinco de Mayo holiday in the United States. The French regrouped, however, and captured Mexico City. They installed an Austrian Hapsburg prince named Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico in 1864.

President Abraham Lincoln’s administration refused to recognize Maximilian and French meddling in Mexican affairs. Lincoln believed this move was a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, which warned European nations that the United States would not tolerate further meddling in Western Hemisphere countries. Conversely, the Confederacy welcomed Maximilian’s government as a possible ally in securing French recognition of the Confederacy. Although Maximilian’s presence in Mexico was unacceptable, President Lincoln had to walk a tight rope in his dealings with France.

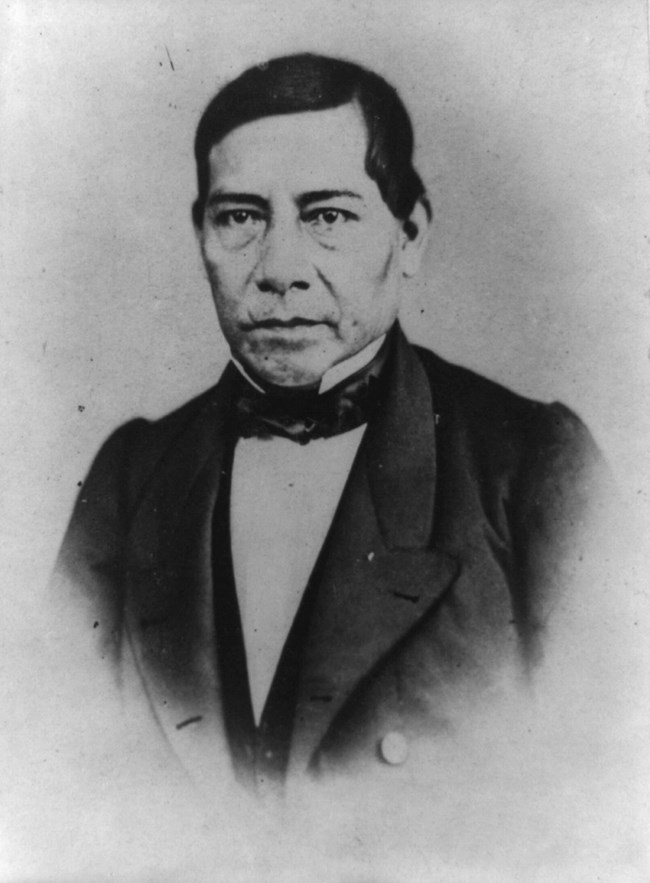

Historian James McPherson notes in Battle Cry of Freedom that Francis P. Blair, Sr., a former member of Andrew Jackson’s presidential administration, concocted a scheme to stop the American Civil War and unite Union and Confederate forces to overthrow the French from Mexico. Although intriguing, President Lincoln did not give the plan much thought and wished to win the war against the Confederacy first. Meanwhile, Mexican resistance forces under Benito Juárez had more military successes. Maximilian needed conservative Mexican support to hold on to power, but alienated them by trying to compromise with political opponents by adopting some liberal policies. This didn't endear him to the liberals because they viewed him as a puppet for the French.

Wikimedia Commons

Ulysses S. Grant emerged as one of the most passionate enemies of Maximilian's government after the American Civil War ended. In a letter to President Andrew Johnson that was written on June 19th 1865, Grant argued that "I regard the act of attempting to establish a Monarchical Government on this continent, in Mexico, by foreign [bayonets] as an act of hostility against the Government of the United States. If allowed to go on until such a government is established, I see nothing before us but a long, expensive and bloody war." Grant then further explained his opposition to Maximilian's government. For one, the French took advantage of the American Civil War to "overthrow Republican institutions" in Mexico. Second, the illicit trading in arms and materials of war between the Confederates and Maximilian’s government further prolonged the Civil War. "Rebels in Arms have been allowed to take refuge on Mexican soil protected by French [bayonets] . . . French soldiers have fired on our men from the South side of the [Rio Grande].”

Not everyone supported Grant’s use of the military in Mexico. Secretary of State William Seward favored diplomacy in dealing with the French. Grant had a willing ally in his subordinate, General Philip Sheridan. Grant dispatched Sheridan to Texas with around 50,000 troops to stop Confederate resistance in Texas, but his forces kept moving closer to the Rio Grande River. Grant even talked about sending liaisons from the U.S. Army to work with anti-imperialistic Mexican forces, while Sheridan talked about crossing the Rio Grande River to hasten Maximilian’s downfall. Ultimately a military battle between the U.S. and French forces in Mexico never happened. The intervention strained French resources and growing tensions with Germany drew France’s attention to events closer to home. Benito Juárez’s anti-imperialistic forces successfully defeated the French, who made a complete withdrawal from Mexico by 1867. Emperor Maximilian was also shot to death by Juárez’s forces that year. Although war with the French over Mexico never happened, Ulysses S. Grant backed up his convictions for self-determination for the people of Mexico.

James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press,1988. pg 683-84.

John Y. Simon, ed. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Volume 15: May 1-December 31, 1865. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1988. Pg. 156-158

US Department of State Office of the Historian. "French Intervention in Mexico and the American Civil War 1862-1867." Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian, Foreign Service.