Part of a series of articles titled French Language and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Article

French Opinion of the American Economy in Early 19th Century

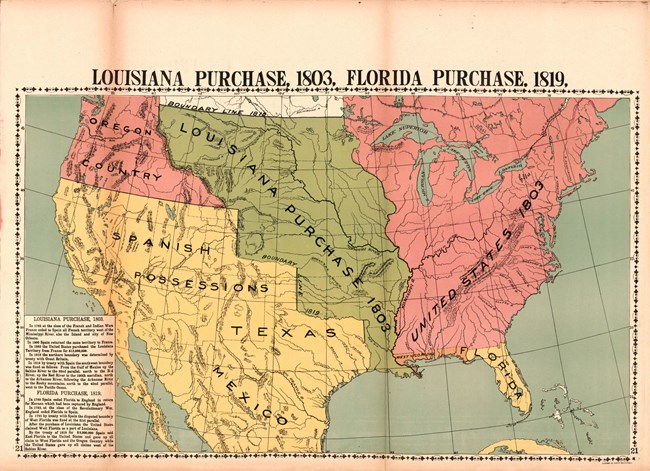

NPS Photo. Public Domain.

This article is one in a series, French Language and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Lewis and Clark Trail Digital Interns.

By the early 18th century, the economic relationship between the United States and France, was close enough that France sold the US 530 million acres of land through the Louisiana Purchase. That was one of the reasons that Lewis and Clark were sent West — to explore all the new land purchased from our European ally (Foreign Service Institute). The close economic ties between the countries gave Frenchmen a close look at the US. Historical documents show us that many French officers felt positively about the US economy, but as the 19th century ushered in a time of unprecedented economic development, France had lingering issues with ideas such as free trade.

There were many positive opinions about early American economic policies. For example, the Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette advocated for the implementation of free trade between the hemispheres, as it was already expanding rapidly in the US. He thought it would be mutually beneficial if free trade existed among the Americas, France, and the French islands (Nicolai, p. 123). Free trade between the United States and Tribal Nations of North America was also a focus for Lewis and Clark. Lewis actively advocated for free trade. In Undaunted Courage, Stephen Ambrose describes how Lewis wanted to build forts along America’s rivers to cultivate trading posts for Native Americans and US traders. Lewis disliked the strict licenses that allowed certain traders to monopolize trade with a specific tribe (Ambrose, p. 443). Most French officers who visited the US acknowledged the economic and demographic strength of the United States, especially compared to the French-Canadian territory that France possessed at the time. Several French officers compared the blossoming American settler economy to the French Republic’s. They were “particularly impressed by the Americans' standard of living, substantial economic equality, and commercial activity” (Nicolai, p. 119).

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. Mcconnell Map Co, and James McConnell. McConnell's Historical maps of the United States.

That said, there was a divide between the Frenchmen who approved and disapproved of early American economic decisions. There’s evidence that many in France viewed Americans as lazy, fur traders as destructive, and merchants as greedy (Nicolai, p. 113). They blamed Americans for food shortages without considering the environmental and market factors that hindered production. There was a widespread belief that American farmers “neglected the principles of scientific agriculture and displayed ‘indolence’ compared to French agricultural workers” (Nicolai, p. 119). In addition, many French officers disagreed with Marquis de Lafayette about the idea of free trade. At the time, the French used tariffs in metropolitan France and their colonies to protect French industries from lower-priced competition. They were unable to accept the implementation of a new trading system (Nicolai, p. 122).

The details in these historical reports are striking. There is evidence that French Captain Lavergne de Tressan, who fought in the American Revolution, once said that “The United States seemed to be dominated by the marketplace (Nicolai, p.120). This statement summarized with remarkable accuracy the US capitalist economy, which dominates the American lifestyle today. It seems early American trade policy was a good indicator of future events. On the other hand, the promising predications offered by the French officers came true as well: free trade contributed immensely to the growth of the world economy, and helped make the US the superpower it is today.

Bibliography

Ambrose, Stephen E. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson and the Opening of the American West, (p. 443). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

Foreign Service Institute. “Louisiana Purchase, 1803.” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/louisiana-purchase.

Hodson, Christopher, and Brett Rushforth. “Bridging the Continental Divide: Colonial America’s ‘French Quarter.’” OAH Magazine of History, vol. 25, no. 1, Organization of American Historians, 2011, pp. 19–24, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23210256.

Nicolai, Martin L. “Trade, Colonies, and State Power: French Officers’ Economic Views on French and English America, 1755-1783.” Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society, vol. 19, Michigan State University Press, 1994, pp. 111–27, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43007768.

Last updated: May 12, 2022