Last updated: June 30, 2021

Article

Frederick Whittaker -- Civil War cavalry officer, best selling author & controversial Custer biographer

Frederick Whittaker: Civil War Cavalry Officer, best-selling author, spiritualist & Custer’s First Biographer, who is buried at St. Paul’s

A cavalry officer, best-selling novelist and spiritualist, Frederick Whittaker is one of the more intriguing figures buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site. He wrote the first and perhaps still most controversial biography of George A. Custer, the American cavalry officer killed at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in June 1876. A Mt. Vernon resident for 20 years, Whittaker worshipped at St. Paul’s Church, and died under mysterious circumstances in 1889.

He was born in England in 1838 and immigrated to New York as a youngster when his father fled to avoid debtor’s prison. In 1861, the 23-year-old was 5’6”, with light hair and blue eyes when he volunteered to help the Union fight the rebellious South, joining the 6th New York Cavalry, lured by the glamour of the horse-riding wing of the army. Eventually rising to officer rank, Whittaker fought with distinction in some of the war’s major engagement, including Gettysburg; he was also wounded, captured, paroled and exchanged. After the war, he purchased a home on South 7th Avenue in Mt. Vernon with money donated by an English relative.

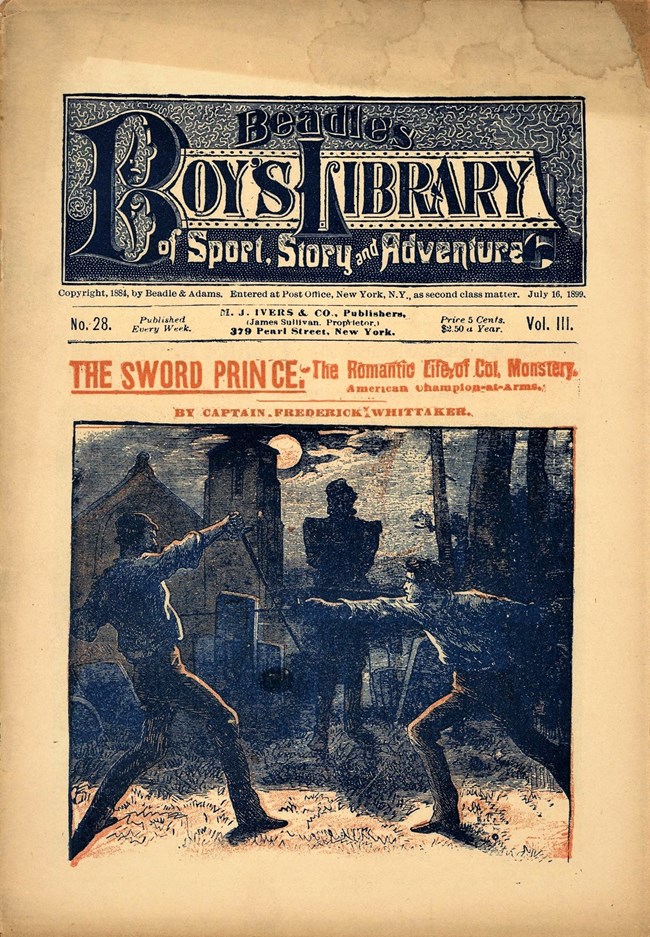

Whittaker married Elizabeth May Houston at St. Paul’s on August 2, 1870, and the couple eventually had three daughters, all baptized at the church. A prominent educator, Elizabeth served as principal of a Mt. Vernon elementary school, a rare achievement for a woman in the 19th Century. The former Union cavalry officer, too, taught school briefly, but, perhaps driven by the same romantic, creative impulse that drew him toward the cavalry, he quickly turned to a writing career, contributing to The Army and Navy Journal, and many widely circulated magazines. In addition, he developed a large and devoted readership base as a pulp fiction writer, producing more than 80 novels over a period of 15 years. From his second story writing studio on South 7th Avenue, he wrote tales set on the colonial frontier, in the Wild West and in Napoleonic Europe; his characters were always brave and dashing figures.

Whittaker met Custer in 1875 at the New York offices of a magazine that was publishing the lieutenant colonel’s memoirs, and the two became friendly. Custer’s annihilation at the infamous Battle of the Little Big Horn, by combined bands of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors June 25-26, 1876, changed Whittaker’s life. Within six months of the defeat, Whittaker published the two-volume, A Complete Life of General George A. Custer. He created a lofty image of his deceased friend Custer as a fearless and brilliant soldier, and “a great man, one of the few really great men that America has produced.” Whittaker also cast blame for the defeat at Little Big Horn on Major Marcus Reno, who had retreated with his contingent of the 7th Cavalry, allowing the Indians to focus on Custer’s command. The charge against Reno set the context for debate over the battle that continues to this day.

In the 1880s, Whittaker dabbled in spiritualism, a belief in communication with the dead, an acceptable pursuit in the 19th Century, especially for the bereaved. His continued interest in history led him to help establish a local historical society that still exists. The author died under circumstances seemingly scripted for a murder mystery, May 13, 1889, in his Mt. Vernon home. As he toppled down the staircase, a bullet discharged from the 38-calibre pistol he usually carried, lodging in his head. Whittaker was known to be in debt, a possible motive for suicide; a coroner’s jury deadlocked on the question of accidental or intentional death. Elizabeth, however, in applying for a widow’s soldier’s pension, asserted, stretching, that the death was suicide -- the climax of tensions created 25 years earlier from her husband’s Civil War combat experience. The argument was accepted by the sympathetic War Department, and she received a monthly widow’s pension until her death in 1925.

Whittaker was interred in the St. Paul’s graveyard on May 15. Beadle and Adams, his pulp fiction publisher, continued to reissue the author’s novels into the 20th Century, and his volumes on Custer inspired many biographers and film makers.