Last updated: January 14, 2021

Article

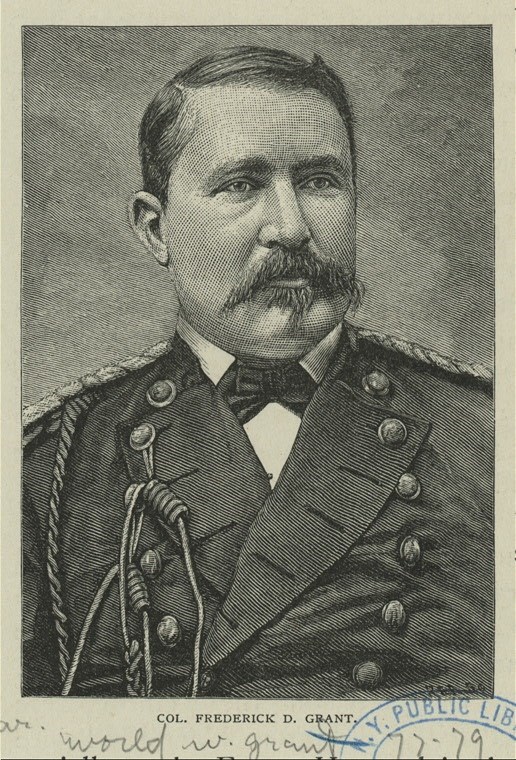

Frederick Dent Grant Joins His Father on the Battlefield

New York Public Library

In today’s military it would be very unlikely to see an officer take his or her child to work, especially if that officer was deployed to a combat zone. In the 1860s, however, things were a little bit different. General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife Julia apparently had no worries about taking their oldest son, 11-year-old Fred Grant, to see a few campaigns during the American Civil War. During the Vicksburg Campaign, General Grant even seemed to think that having Fred follow along with the armies would be good for his development. Grant wrote in a letter home, “He enjoys himself finely, and I doubt not will receive as much perminant (sic) advantage by being with me for a few months as if at school.”

Fred began following his dad to work early in the war. Not long after Grant was promoted to the rank of colonel in the 21st Illinois Infantry, Fred was riding through the Illinois countryside with the 21st from Springfield to Quincy, Missouri in July 1861. Colonel Grant believed that his son was having a great time as an unofficial member of the 21st. Grant wrote home, “Fred enjoys it hugely. Our Lieut. Col. was left behind, and I am riding his horse so that Fred has Rondy to ride. The Soldiers and officers call him Colonel and he seems to be quite a favorite.”

Fred experienced the war firsthand when he accompanied his dad during the Vicksburg Campaign in 1863. General Grant wrote home that, “Fred is very well enjoying himself hugely. He has heard balls whistle and is not moved in the slightest by it. He was very anxious to run the blockade of Grand Gulf.” The general may have believed that his son was “not moved” by the sights and sounds of war, but Fred painted a different picture years later. In a speech from 1898, Fred remembered his time at Grand Gulf while moving down river in a Union gunboat. He was horrified by what he saw much more than his father realized. Fred said, “…I was sickened by the scenes of carnage. Admiral [Horace] Porter had been struck on the back of the head with a fragment of shell, and his face showed the agony he was suffering, but he planned a renewal of the conflict for that night.” The admiral tried to convince Fred to take the place of a gunner who had been lost, but he declined. Fred told those attending his speech: “The scene around me dampened my enthusiasm for naval glory, so I replied: “I do not believe that papa will allow me to serve in the navy.”

As Grant’s forces moved inland towards Jackson, Mississippi, Fred saw more scenes that were etched in his memory forever. After a battle at Raymond, Mississippi, Fred remembered walking through the battlefield: “here again I saw the horrors of war, the wounded and the unburied dead.”Just a few short days after seeing the slaughter of Raymond, Fred narrowly missed possibly being killed or captured inside the capitol city of Jackson. Fred thought the city had fallen and rode his horse inside the town. This maneuver proved to be premature. “Thinking the battle was ended,” Fred remembered, “I rode off toward the state-house, where the Confederate troops passed me in their retreat. Though I wore a blue uniform I was so splashed with mud…that the Confederates paid no attention to me. I have since realized that even had I been captured it would not have ended the war. Fred wasn’t as lucky in the coming days of the campaign.

General Grant continued to pursue the Confederates towards Vicksburg after his army destroyed everything of military value inside the capitol. Fred was still with his dad as they encountered the rebels at Champion’s Hill, and at Big Black River Bridge. Fred earned his “Red Badge of Courage” during the battle on the Big Black River. As Fred watched the Confederates escape across the river, he recalled: “…I was watching some of them swim the river when a sharpshooter on the opposite bank fired at me and hit me in the leg. The wound was slight, but very painful, and I suppose I was very pale, for Colonel Lagow came dashing up and asked what was the matter. I promptly said, 'I am killed.' Perhaps because I was only a boy the colonel presumed to doubt my word, and said, 'Move your toes'-which I did with success; he then recommended our hasty retreat. This we accomplished in good order.”

Fred recovered from the wound he had received at the Big Black River before staying with his dad for the remainder of the campaign until the siege had finally ended in early July 1863. Fred was with his dad when the Confederates sent word through the lines that they would surrender. Fred was one of the first people to hear the good news. Fred reminisced: “I was thus the first to hear officially announced the news of the fall of the Gibraltar of America, and filled with enthusiasm, I ran out to spread the glad tidings. Officers rapidly assembled, and there was a general rejoicing." Fred was ill during the last days of the Siege of Vicksburg and later sent back home. He later said, “This ended my connection with the army for a while. From the result of exposure, I had contracted an illness, which necessitated my withdrawal into civilian life again.”

Fred returned to his father’s side again after the battle for Chattanooga, and would travel to Washington, DC with his dad when he was promoted to command all Union armies. “President Lincoln received my father most cordially,” Fred remembered, “taking both hands, and saying, “I am most delighted to see you, General.” I myself shall never forget this first meeting of Lincoln and Grant.”

Fred graduated from West Point, just like his father, six years after the end of the Civil War in 1871. He served in the army during the 1870s before leaving to work for a railroad company. The military life would once again draw him back and he was promoted to the rank of General during the Spanish-American War, where he served in Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Fred was a heavy smoker and later passed away in 1912 at the age of 62 from cancer, much like his father had died of cancer in 1885.

"A Chat with Fred Grant," St. Louis Republic, August 21, 1904.

Frederick Dent Grant, "General Grant as a Father," Youth's Companion 73, no. 3, January 19, 1899.

Frederick Dent Grant Speech to the Illinois Commandery of the Loyal Legion of the United States, January 27, 1910.

"General Fred Grant's Scare at Vicksburg," Literary Digest 44, no. 17, April 27, 1912.