Last updated: February 6, 2025

Article

Seeking Fortune: The Revolutionary Path(s) of Fortune Freeman and Fortune Conant

Library of Congress

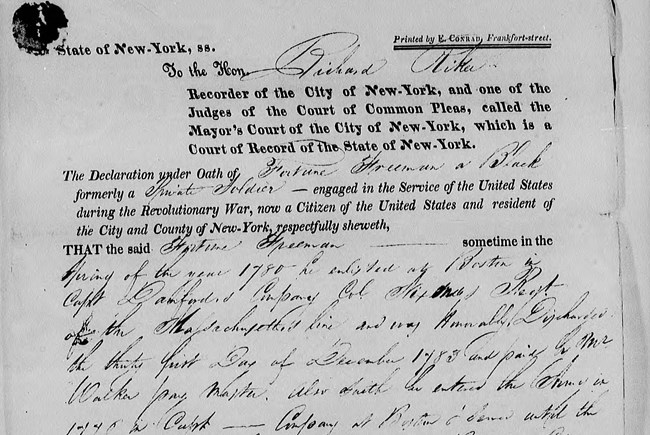

In the spring of 1818, an old man named Fortune Freeman appeared before the Mayor's Court of New York City. Whether there of his own volition or brought to the court by a city official, it remains unclear, but Freeman, "extremely poor"[1] and unable to work, swore to the court that he served as a soldier in the Revolution, and applied for a veteran's pension for some relief. Arriving to the court with merely the clothes on his back, Freeman provided few details about his personal life in his statement. Aside from his own declarations, few records of his life exist before or after the war. Only one of these precious few records remained in his possession when he approached the court: a discharge paper from the 4th Massachusetts, issued to him at the close of the Revolutionary War in 1783.

Originally from Massachusetts, Freeman moved to New York City at some point after the war. The Black private joined thousands of other veterans in a post-war exodus from their home states.[2] Freeman did not have a unique experience as a veteran in poverty. He became one of 20,000 Revolutionary War veterans[3] who filed for a pension by the end of 1818 following the passage of a pension bill that same year. The law promised pensions to veterans "in reduced circumstances"[4] who had served at least nine months in the Continental Army. Ten thousand more veterans applied the following year. When Congress first passed the law, they expected fewer than 2,000 eligible applicants[5] and estimated that it would cost $155,000.[6] Congress estimated wrong. By the end of 1818, the program cost nearly $2 million.[7]

Old, destitute, and with little else to rely upon, Freeman sought financial assistance from the country he served for nearly six long years. In his pension application, Freeman claimed to have first enlisted in Boston in 1776 in Captain Elijah Danforth's company, Colonel Thomas Nixon's regiment, later designated the 6th Massachusetts Regiment in 1779. He stated that he continued to serve in the same regiment until his honorable discharge in 1783. However, when looking through muster rolls, there is no record of a "Fortune Freeman" enlisting in 1776 in Danforth’s company. In fact, there is no record of a "Fortune Freeman" in Danforth's company at all. Furthermore, Fortune Freeman presented a discharge from the 4th Massachusetts, but Danforth's company served in what later became numbered the 6th Massachusetts. There is, however, a "Fortune Conant" who enlisted in Elijah Danforth's company in 1777. And then later, records show that a "Fortune Freeman" enlisted in 1781 into the 4th Massachusetts, serving until discharge in 1783. Is it possible these two different identities tell the same story?[8] Might a man named Fortune Conant, possibly enslaved, who may have been freed during service, changed his name, stating for all of posterity his status of being a "free man" prior to reenlisting in 1781?

A lack of records is not unusual for revolutionary soldiers, particularly soldiers of color, but Freeman's claims are illustrative of the experiences many soldiers of color experienced during the American Revolution. What follows are two stories presented as part of a possible whole: one of a man named Fortune Conant, who served for three years from 1777-1780, and disappeared after his discharge, and another about a man named Fortune Freeman, who claimed to have served the entirety of the war, struggled to live a life in the new nation in New York City, and ultimately died in poverty. These stories, whether of the same man or not, are examples of how little information exists about soldiers, particularly those of color, who played a critical role in the founding of the United States.

Part 1: Fortune Conant

In Fortune Freeman's testimony about his Revolutionary war service, he remembered enlisting under a Captain Elijah Danforth in 1776. However, no records indicate that a Fortune with the surname "Freeman" ever served under Danforth. However, a Fortune with the surname "Conant" did. Throughout his pension testimony, Freeman only names one company captain that he served under — Captain Danforth. It is curious that of all the details to remember from six years of military service, his possible first captain is the only name that remained etched into Fortune Freeman's memory. It is possible that Fortune Conant, a young man who enlisted either enslaved or perhaps recently freed, later changed his name. Might this be the same Fortune Freeman who later reenlisted, and eventually filed for a pension? Part one of this story follows Conant's paper trail and examines how it aligns with Fortune Freeman's own testimony.

Henry Allen Hazen, "History of Billerica, Massachusetts, with a Genealogical register."

Stop 1 — Pre-1777, Billerica, Massachusetts

Born sometime between 1747 and 1760,[9] Fortune Freeman lived in Massachusetts until at least the start of the American Revolution. Though Freeman reveals nothing of his pre-war life in his pension record, Fortune Conant is credited to Billerica, Middlesex County, Massachusetts, for the purpose of the town meeting their recruitment quota for the war effort.[10]

The Conant family name in Massachusetts turns up throughout the history of the state. Though a few probate records indicate some Conant family members enslaved people of African descent, Fortune's name does not appear in any of these surviving records. Fortune Conant's name also does not appear in any land records.[11]

In a History of Billerica, Massachusetts, a William Conant is listed as taxed in the town from 1776 to 1779, and his daughter Betsey, is stated as being baptized there in August 1795.[12] Though no definitive connection could be found between this William and Fortune, it does put the Conant family in the region at the time when Fortune joined the war.

Without finding Fortune's name in any Conant family records, we are left with questions about his early life. Was he enslaved by the family? Was he born into slavery? Was he freeborn? Where did he come from? Who were his parents? Did he have any other family? The name Fortune Conant appears only in muster rolls.

Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804.

Stop 2 — May – June 1777, Boston, Massachusetts

"Forten" Conant first appears on a list of men mustered by Colonel James Barrett, muster master of Middlesex County, on May 16, 1777.[13] Fortune Conant is listed as joining Elijah Danforth's company — the same company Fortune Freeman remembered joining over 40 years later when he applied for his pension in New York City. Later muster rolls state that Fortune Conant officially enlisted in the Continental Army a few weeks later on June 4, 1777.[14] If Fortune Freeman's memory is correct — and he originally joined as Fortune Conant — he came to Boston after accepting a bounty and passing muster in Middlesex County and enlisted for the term of three years.

If the men are the same, Elijah Danforth is also the most solid connection we have to Billerica being Fortune Freeman's hometown. Captain Danforth and his family lived in Billerica for years, with Danforth even serving as a minute man in 1775.[15] Freeman may have recalled Danforth easily as a familiar name to him in his younger days. Was Danforth's promotion to captain and participation in the war a motivating factor in Conant's enlistment? Furthermore, Danforth served on a committee chosen by the town of Billerica to call on "persons to inlist [sic] into the Continental service."[16] Perhaps these recruitment efforts helped Fortune Freeman remember Danforth's name so many decades later. It is very likely Fortune Conant collected a bounty of £24 from Billerica, £20 from Massachusetts, and 20 dollars from the Continental Congress as bounty payments when someone finally convinced him to enlist.[17]

Examining the possible connection between Fortune Conant and Fortune Freeman can help uncover potential motivations Freeman had for enlisting in the war. If Freeman was Conant, was he promised freedom to join or was he merely hopeful that freedom could be a possibility? Though monetary value depreciated as the war progressed, were bounty payments used to purchase his freedom? Was there hope for financial independence following the war? Was he enticed by the hope for a new nation? Did he feel a sense of pride in the idea of independence? Though we do not know why Freeman enlisted to fight, something persuaded him to join in the fight for independence and something kept him in the war for over six years.

John Trumbull; Architect of the Capital

Stop 3 — Fall 1777

Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, or Saratoga, New York?

In his pension application, Fortune Freeman asserted his presence at several well-known and significant battles during the Revolutionary War. But his assertions complicate understanding if Fortune Freeman and Fortune Conant were same person. Fortune Freeman recalled that he participated in the September 11, 1777 Battle of Brandywine, where he claimed to have been "wounded in the thigh by a musket ball."[18] But he also said he witnessed the surrender of General John Burgoyne following combat at the Battle of Saratoga, which took place in October 1777 in upstate New York. Fortune Conant, a member of Thomas Nixon's Regiment, would have been at Saratoga, not Brandywine. However, recalling a wound at Brandywine, specifically, complicates understanding the story of Fortune Freeman.

During the Battle of Brandywine, Washington attempted to prevent the British army from taking Philadelphia, the patriot capital. The Continental Army lost the battle and retreated, leaving Philadelphia in English hands, though most of Washington's troops survived.

At the Battle of Saratoga, Continental forces succeeded in forcing British Lieutenant General John Burgoyne's surrender in a dramatic victory for the cause of American independence. It is highly unlikely that Freeman saw action both at the battles of Brandywine and Saratoga: The battles took place hundreds of miles apart and only a few weeks separated them. Additionally, no recorded Massachusetts regiments participated at Brandywine during the battle. If he served as part of Nixon's regiment, it is much more likely that he fought in Saratoga.

But if Freeman was not at Brandywine, was he still injured in the war? Perhaps he was, and he simply misremembered the battle. It is also entirely possible that Freeman felt that mentioning an injury would help his case for a pension, or someone encouraged him to embellish his story. At the time of his application, Freeman showed his dire need for financial help. What would a desperately poor man claim to guarantee financial relief? Whether Freeman misremembered his experiences or stated an additional battle to gain his pension, it is significant that he chose to state his presence at both battles.

According to the surviving records, though, Fortune Conant served with Nixon's regiment in the late summer and fall of 1777. When word arrived that General John Burgoyne and his men began to march into New York from Canada, Nixon's regiment received orders to support General Horatio Gates and the Northern Department, serving the area of New York north of New York City.[19] Nixon's men comprised part of the main body of Gates' men during the September 19 Battle of Freeman's Farm and continued the campaign through the next month.[20] After a series of October battles, Burgoyne found himself surrounded by Gates' men and surrendered on October 17. This series of battles and Nixon's presence in New York starting in July further support the idea that Freeman served at Saratoga and not Brandywine and witnessed a pivotal turning point in the American Revolution.

Library of Congress

Stop 4 — Mid-1778, White Plains, New York

Though we do not know Freeman's exact journey, he claimed to have fought next in the June 1778 Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey. Towards the end of March 1778, Nixon's regiment moved to the Highland's department, overseeing the defenses of the Hudson River near New York City. However, there is no record of Nixon's regiment at the Battle of Monmouth.

Fought in one day, on June 28, 1778, the Battle of Monmouth resulted in no clear victory for either Washington's troops or the British. Following the stalemate, Washington established camp at White Plains, just north of New York City.[21]

Again, though no "Fortune Freeman" is listed with Nixon's men, Fortune Conant is documented on record at White Plains on September 9, 1778, with Danforth's company in Nixon's regiment, a few months after the Battle of Monmouth.[22] If Freeman settled at camp with men who fought at Monmouth, he would have heard conversations about the battle. Perhaps in his old age, he believed he fought alongside those men, or maybe he embellished his service in the hopes of his pension application being accepted.

From there, Freeman did not mention any specific event until 1780, but muster rolls document Conant's presence in 1779.

General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Stop 5 — 1779 - 1780, New York

According to military records, Conant stayed with his company in Nixon's regiment throughout 1779, moving to various positions to keep British forces contained within New York City.

From March to May of the same year, he appeared on muster rolls dated at King's Ferry, a major crossing point on the Hudson. On one copy of a muster roll from April, Conant is listed as "on command on the lines."[23] This possibly means that Conant served on a mission outside of camp — raids and skirmishes frequently took place as both the Continental and British forces tested each other's defenses. [24]

At the end of May and beginning of June, the British returned to King's Ferry. Their attack pushed the Americans out of the crossing.[25] Following this attack, Nixon's regiment retreated to the "Highlands" in New Jersey on June 12, and Conant is still listed on pay rolls and clothing receipts through September.[26]

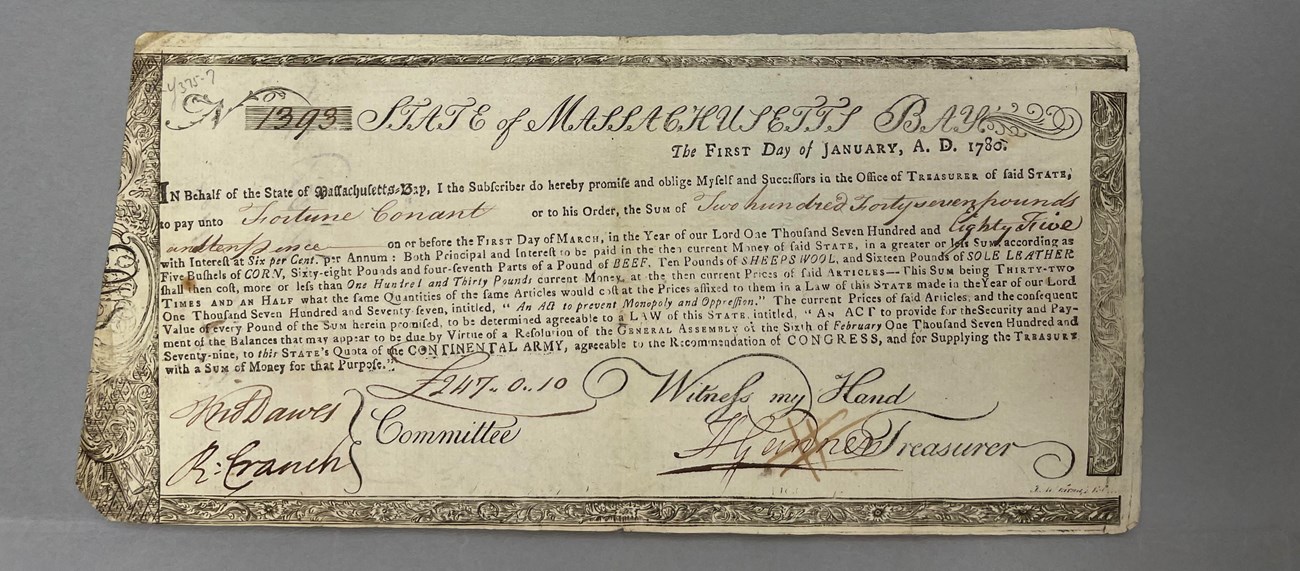

Following the muster roll trail leads Conant to Bedford, New York.[27] By December, he appears once again in an account of soldiers receiving clothing at camp in Peekskill.[28] Conant also appeared in a bounty note issued by the State of Massachusetts Bay on January 1, 1780.[29] Discharged on June 4, 1780, completing his three-year enlistment, Fortune Conant does not appear in any further military records.[30]

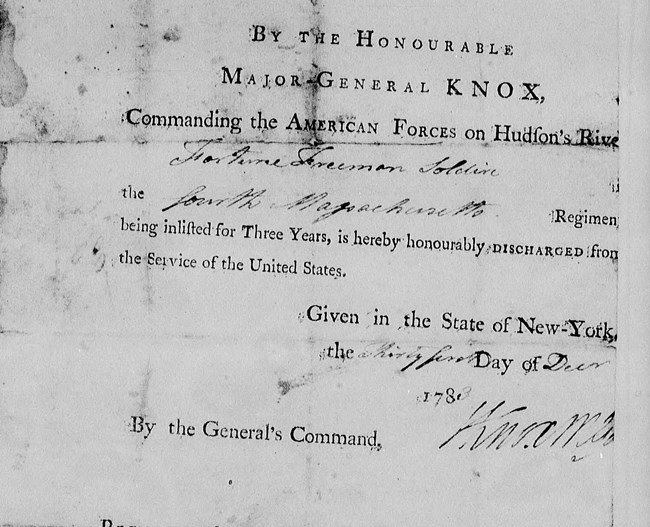

In his pension, Freeman stated his discharge in 1780, which lines up with Conant's discharge. He then said he reenlisted in Boston in 1780 into the same company and regiment. There is no record, however, of any Fortune — Freeman or Conant — that served in Nixon's regiment after June 4, 1780. But when Fortune Freeman applied for a pension, he included one tattered sheet of paper that confirmed a discharge in 1783 from the 4th Massachusetts Regiment, which does have a record of a Fortune Freeman, who enlisted in 1781 and served until the end of the war. With that tattered discharge note, we now can follow Fortune Freeman's paper trail, which begins in 1781 in Hingham, Massachusetts.

Part 2: Fortune Freeman

Library of Congress

Stop 1 — Early 1781 – Hingham, Massachusetts

The Fortune Freeman who enlisted in the 4th Massachusetts and is discharged from the 4th Massachusetts, enlisted in March 1781 in Hingham, Massachusetts.[31] He served in Elnathan Haskell's company, William Shepard's regiment.

If Fortune Freeman is Fortune Conant, it is possible that he returned to Boston after his first discharge. When he returned to Massachusetts, he may have been able to finally claim freedom for himself. Hingham, though much smaller than Boston, sat on the same vital harbor that brought in goods, and more importantly in the later war years, support from France in the form of troops, arms, and money. Freeman may have moved to Hingham to try and start a new life as maritime towns had generally more job opportunities than farming towns. Nevertheless, perhaps he encountered difficulties with work, and his bounty monies did not hold out as long as he had hoped. When Fortune Freeman enlisted in 1781, it brought the guarantee of pay. If Freeman had bounty bonds from prior service as Fortune Conant, they would not mature until 1785. His bounty payments would not have hit their full value so soon after his first discharge. In addition to the bonds not maturing, the Continental currency continued to devalue over the course of the war.

Library of Congress

Stop 2 — Summer 1781 — Arriving at New York: Familiar, or maybe new?

By June, Freeman arrived in West Point, New York and appeared on muster rolls for Haskell's company.[32] Through August and September, Freeman is described as "on command," meaning he likely traveled on small missions or duties outside of camp.

If Freeman served earlier in the war as Fortune Conant, he would have already been familiar with the New York terrain, and in the intervening months between his possible first discharge and his reenlistment, not much had changed. After 1778, a stalemate set in around the New York area, with no major campaigns. The British Army focused instead on a campaign in the southern colonies, with an army under General Cornwallis engaging Continental forces in the Carolinas. But when Cornwallis marched his army toward the Chesapeake Bay, Washington saw an opportunity to strike. The experience of veteran soldiers such as Freeman would prove crucial in the fall of 1781.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Stop 3 — Fall 1781 – 1782, Yorktown, Virginia

For Washington to split his army and keep half in New York and half on the march, he had to assemble units quickly that could march with speed.

It appears that Freeman, presumably because of his lengthy combat and campaign experience, is listed as "on command" with a Colonel Alexander Scammel, who led a New Hampshire regiment.[33] Appointed Adjutant General of the Continental Army by General George Washington in January 1778, Scammell held that position until he requested permission to resign his post and resume command of a regiment in November 1780.[34]

In 1781, Washington ordered the formation of a light infantry regiment commanded by Scammell, "with a view of having a Corps ready to execute a project of the kind which I shall propose to you, which is to endeavour [sic] to strike, by surprise, [enemies establishing themselves at or near Fort Lee]."[35] Composed of men from Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, the regiment marched South to Yorktown, engaging in skirmishes along the way, and served as part of the 2nd brigade of The Light Infantry Division during the Siege of Yorktown.[36]

The final event Freeman explicitly mentioned in his pension application is the capture of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis and his army, after the Siege of Yorktown, which lasted three weeks. If Freeman is the same man "on command" with Scammell, he undoubtedly fought at Yorktown.

By November, Freeman transferred from his command post back to Haskell's company. He appeared on muster rolls for York Hutts, an encampment in New Jersey, from November 1781 to January 1782.

His paper trail then goes blank until 1783.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Stop 4 — 1783 – West Point, New York

On December 31, 1783, Freeman received his honorable discharge from the 4th Massachusetts Regiment, having been enlisted for three years.[38] The 4th Massachusetts disbanded in West Point, New York in November of 1783. It is likely that Freeman decided to stay in New York after his discharge.

If Freeman declared or received his freedom during the war, he most likely did not have a home of his own to return to. More than 200 miles from his enlistment site in Boston, he may have chosen to start afresh in a new location.

So far, we have been unable to locate any land records indicating where Freeman settled after the war. It is also unknown what work he pursued. The only definitive information about Freeman’s post-war life is that he resided in New York City by 1818. Aged and infirm, he could no longer work and support himself.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Stop 5 — 1820-1824, New York City, New York

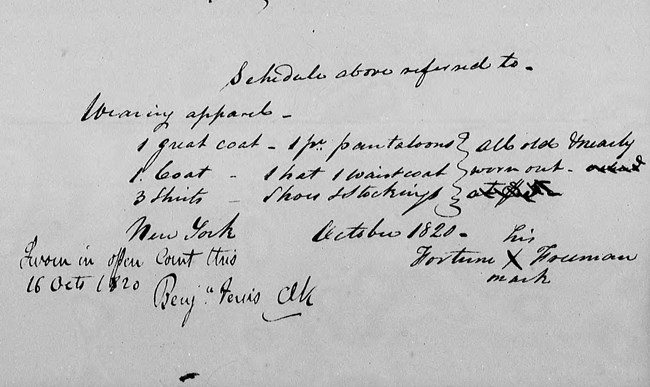

By 1820, Congress amended the 1818 Pension Act. "It required all claimants to submit documentation of their poverty to a court of record. Each applicant had to disclose his age, occupation, health, and ability to support his household, and an inventory of his real and personal property."[39]

Following this amendment, Freeman reapplied. While his wartime declarations remained the same, he provided additional personal information in his restatement per the requirements and described his dire circumstances.

Freeman swore to his inability to work and need for government assistance to survive, declaring:

I am infirm, and unable to labour, except in doing light work in which I can only obtain casual employment, and for which I can obtain scarcely more than mere nominal wages. And that I have no other means of obtaining a subsistence, except the pension allowed by Congress, and do actually need the assistance of my country to prevent my being dependent on charity.[40]

He provided a sparse list of apparel described in the record as "all old and nearly worn out."[41] He also said that he had no family aside from an 18-year-old daughter named Mary and revealed her status as "bound out to service."[42] Was Freeman previously married, and if so, did his wife die? What about his parents or any siblings? As for Mary, why was she bound out, and when did her service start?

With no other information provided, Mary's terms of service are unknown, and it is unclear what happened to her later in life.

By providing evidence of his need, Freeman continued to receive his pension. Payment records indicate payment through September 1824, but they end with no explanation.[44] Freeman may have died in September, possibly between the ages of 64 and 77. It is also possible that he lost contact with the pension program by moving, whether of his own volition or forced by outside circumstances. His cause of death or later whereabouts remain unknown.

Despite the questions surrounding Freeman's life, it is certain that he dedicated years of his life in the fight for a new nation. When he needed financial assistance, he turned to the new country he served for help. Freeman’s story is just one of the thousands of patriots of color that we can attempt to unravel by searching existing pension records, though thousands more did not get recorded. Some enslaved men found freedom in fighting. Others, born free, joined and fought for home, country, and a hope to get any financial footing in life. Records only give us a part of someone’s life, and sometimes they are misremembered, forgotten, or incomplete. And sometimes, the paper trail ends without any conclusive findings. But the stories of these men are important to tell when we look back at our nation’s founding to see who served in the war that secured the independence of the United States.

Contributed by Anjelica Oswald, Digital Public History Intern

Footnotes

[1] Fortune Freeman, Pension No. S 43,572, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 4, via Fold3.com.

[2] A preliminary study of pension records from 1981 found that of 13,500 Revolutionary War veterans, more than half (54 percent) had moved from their home state after the war. Theodore J. Crackel, "Longitudinal migration in America, 1780-1840: A study of Revolutionary War Pension Records," Historical Methods 14 (Summer 1981): 133-137.

[3] Jack D. Warren Jr., America's First Veterans (Washington, DC: American Revolution Institute of the Society of Cincinnati, Inc., 2020), 97.

[4] Ibid, 89.

[5] John P. Resch. “Politics and Public Culture: The Revolutionary War Pension Act of 1818.” Journal of the Early Republic 8, no. 2 (1988): 139–58.

[6] Warren Jr., America's First Veterans, 97.

[7] Ibid.

[8] While a Ph.D. candidate in History at Brandeis University in 2013, John Hannigan, current head of reference services at the Massachusetts State Archives, wrote a blog post about Fortune Freeman's pension record. Hannigan wrote that digging into muster rolls led him to "to believe that Fortune Freeman was originally a slave from Essex County, Massachusetts named Fortune Conant." John Hannigan, "The Many Lives of Fortune Freeman," Rethinking the Age of Revolution, Blogs @ Brandeis, 10 December 2013, https://blogs.brandeis.edu/revolutions/2013/12/10/the-many-lives-of-fortune-freeman/.

[9] Freeman is described as "seventy-one" in his 1818 pension but is "about sixty-five" in his 1820 record, but Hingham enlistment records describe him as 21 in 1781. We were unable to find any birth record for Fortune Conant. Fortune Freeman, Pension No. S 43,572, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, pages 4 and 9, via Fold3.com. Bounty receipts: Suffolk, Essex, and Middlesex counties 1781-1782, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 32, Image 104, via FamilySearch.org.

[10] Field and staff rolls 1775-1780, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 27, Image 523, via FamilySearch.org.

[11] Fortune is, however, included in a genealogical history of the Conant family, but the only information included says that he lived in Billerica and served three years in the Continental Army. Frederick Odell Conant, A history and genealogy of the Conant family in England and America, thirteen generations, 1520-1887: containing also some genealogical notes on the Connet, Connett and Connit families (Portland, ME: 1887), 557. Archive.org.

[12] Henry Allen Hazen, History of Billerica, Massachusetts, with a Genealogical register (Boston: A Williams & Co, 1887), 25. Archive.org.

[13] The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, Vol. 50, ed. John Ward Dean, A.M. (Boston: New England Historic and Genealogical Society, 1896), 474.

[14] Records of Military Operations and Service: Officers and Enlisted Men. NARA M853, page 64, via Fold3.com.

[15] Town records 1685-1779 Billerica, Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986, Middlesex County, Image 598, via FamilySearch.org.

[16] Hazen, History of Billerica, Massachusetts, with a Genealogical register, 238. Archive.org

[17] The committee in Billerica voted for an additional bounty of £24 to "such persons as will now Inlist into the Continental Army" but they needed to figure out how the money would be raised for the additional bounty. Hazen, History of Billerica, Massachusetts, with a Genealogical register, 239. Archive.org. It is also worth noting that the dollars were paid in Continental dollars which were quickly depreciating in value. Inflation and depreciation meant that these bounty payments were not worth their face value by the time soldiers were paid. Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts 1776-1777, Vol. 52, Part 2 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1986), 184, via Haithi Trust.

[18] Fortune Freeman, Pension No. S 43,572, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 4, via Fold3.com.

[19] "Massachusetts Regiments in the Continental Army," RevolutionaryWar.us, https://revolutionarywar.us/continental-army/massachusetts/.

[20] Henry B. Carrington, MA, LLD, Battles of the American Revolution 1775-1781. Historical and Military Criticism, with Topographical Illustration (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1876), 336.

[21] "The American Revolution Timeline," George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/george-washington-papers/articles-and-essays/timeline/the-american-revolution/.

[22] Fortune Conant, Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. NARA M881, page 5, via Fold3.com.

[23] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783. NARA M246, page 150, via Fold3.com.

[24] Judith L. Van Buskirk, Standing In Their Own Light: African American Patriots in the American Revolution (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017), 118.

[25] "The American Revolution Timeline," George Washington Papers, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/collections/george-washington-papers/articles-and-essays/timeline/the-american-revolution/.

[26] Muster roll of Lieut. Col. Calvin Smith's Company in the 5th Battalion of Massachusetts Bay Forces in the Service of the United States comm by Col Tho Nixon for May 1779, Muster and payrolls 1777-1780, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 48, Image 88, via FamilySearch.org. Ceys, Danforth - Dean, Samuel, Muster rolls (index file cards) of the Revolutionary War, 1767-1833 [Massachusetts], Image 1193, via FamilySearch.org.

[27] Fortune Conant, Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. NARA M881, page 4, via Fold3.com. Pay Roll of Lt. Col. Daniel Whiting’s Company in the 6th Battalion of Mass Bay Forces Commanded by Col Tho Nixon for Nov 1779, Muster and payrolls 1777-1780, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 68, Image 673, via FamilySearch.org.

[28] An Account of Clothing Delivered Lt. Colonel Company Peekskill, Muster/payrolls, and various papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 69, Image 144, via FamilySearch.org.

[29] Bounty note, no. 1393, issued by the State of Massachusetts Bay, for the sum of 247 pounds and 10 pence, in favor of Fortune Conant: dated January 1, 1780: date for maturity: March 1, 1785. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

[30] Records of Military Operations and Service: Officers and Enlisted Men. NARA M853, page 64, via Fold3.com.

[31] Muster/payrolls, and various papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 32, Image 99, via FamilySearch.org.

[32] Muster Roll of Capt. Elnathan Haskell's Company in the 4th Massachusetts Regt. in the service of the United States Commanded by William Shepard for the Month of May 1781, Muster/payrolls, and various papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 50, Image 664, via FamilySearch.org.

[33] Muster Roll of Capt. Elnathan Haskell's Company in the 4th Massachusetts Regt. in the service of the United States Commanded by William Shepard for the Month of September 1781, Muster/payrolls, and various papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 50, Image 668, via FamilySearch.org.

[34] "To George Washington from Alexander Scammell, 16 November 1780," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-03961.

[35] "From George Washington to Alexander Scammell, 17 May 1781," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-05812.

[36] "Alexander Scammell," The Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Hampshire, https://www.socnh.org/alexander-scammell/.

[37] "From George Washington to William Heath, 29 October 1781," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07314.

[38] Fortune Freeman, Pension No. S 43,572, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 13, via Fold3.com.

[39]"About 4,000 (22 percent) of the beneficiaries under the 1818 act chose not to submit to a means test. By February 1822, nearly 12,000 veterans were back on...about 20,000 veterans took the pauper's oath and submitted to the means test; and all but 2,000 got the benefit." John P. Resch. "Politics and Public Culture: The Revolutionary War Pension Act of 1818." Journal of the Early Republic 8, no. 2 (1988): 139–58.

[40] Fortune Freeman, Pension No. S 43,572, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 10, via Fold3.com.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] "New York (State). State Board of Charities," Social Networks and Archival Context, https://snaccooperative.org/ark:/99166/w6129qv4.

[44] United States Revolutionary War Pension Payment Ledgers, 1818-1872, Vol. 1, Image 114, via FamilySearch.org.