Last updated: May 6, 2025

Article

Footnotes in Time: The Badlands Epoch

NPS Photo | Vince Santucci

The Researcher

While a master’s student at the University of Pittsburgh in the 1980s, Vince Santucci was fascinated by the nearly continuous record of fossil mammals 1,300 miles away at Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Millions of years of evolution, environmental change, and biodiversity had long been studied by prominent paleontologists, but there still seemed to be a missing piece to the story. Interpretations of fossil-rich Oligocene-age deposits (~30 million years old) between South Dakota and Nebraska were not congruent. How could you better constrain the timing of major shifts in endemic faunas? Vince decided to investigate this question using a novel method: paleomagnetism. Throughout Earth’s history, our north and south poles have “flipped” and reversed in unpredictable but detectable intervals. When they form, magnetic minerals within some types of rocks line up with the Earth’s poles, just like the needle on a compass. Hidden from the naked eye, the fingerprint of Earth’s polarity within rocks and minerals can reveal the timing of their deposition and help correlate fossil-bearing deposits across large geographic areas. With careful training, Vince uncovered the timing of a critical transition in faunas, including now-extinct creatures such as rhinoceroses, horses, camels, entelodonts (hooved mammals resembling large pigs or hippos), oreodonts (sheep-sized cud-chewing hooved mammals), opossums, bone-crushing dogs, shrews, rabbits, and rodents such as chipmunks, beavers, gophers, and kangaroo mice.This research took many long days of hiking around rock outcrops and taking samples. Far from home, Vince’s pockets were starting to run dry. With a new familiarity and appreciation of his natural laboratory at Badlands National Park, he decided to apply for a seasonal Park Ranger position. It turned out that research paleontologists aren’t the only ones to learn from in situ fossils.

Courtesy Vince Santucci

The Ranger

Right away, Vince realized he was part of something special when he joined the National Park Service team at Badlands: “So, here we are on day one going into training, and I quickly learned that Badlands was recognized in the region as being one of the best interpretive experience opportunities. And so, I was spoiled as a young Ranger to be part of this team.” While all of the Rangers were encouraged to learn about the park’s landscape, plants, animals, and geology, their chief, Dave McGinnis, selected individuals to further specialize in particular topics. He had an assignment for Ranger Vince: to be the park’s paleontologist. With apprehension, Vince responded “Well, look, I'm new here. I'm just learning,” but Dave was confident in his choice. “[Dave] said I hired you because I trust that you will take that very seriously and make sure that you understand and help share that information with all the other Rangers and the public. And so, I took that very, very seriously. And I read every publication in the park’s library, and I talked to every geologist and paleontologist who worked in the Badlands. I took the field guidebooks, and I went out on my days off to visit sites in plainclothes to know and understand the geology and paleontology of Badlands.”Vince began taking visitors on hikes to see fossils in their original context and noticed something remarkable: people with little to no background in paleontology started spontaneously asking scientific questions. This was different from people viewing exhibits at his hometown Carnegie Museum; they started to ask questions focusing on the context of these fossils. “What kind of environment did this animal live in and how can you tell that from the rocks?” Vince also got to witness people making lasting memories. “That's your eyes seeing this thing for the first time in 30 million-plus years…This was a really important, meaningful connection for people, so they understand why we do what we do in the National Park Service to protect these nonrenewable resources.” While every fossil on Earth is finite, they hold potentially infinite opportunities for creating memories and inspiring connection. Still, not everything Vince saw were postcard moments. Occasionally while out exploring the badlands, Vince noticed something unusual and suspicious: In more remote areas of the park, irreplaceable fossils were disappearing into the pockets of fossil poachers.

The Investigator

Filled with adrenaline, Vince rushed back to the Ranger Station. “Come on, we gotta get out there and get these bad guys that are stealing fossils!” Chief Law Enforcement Ranger Lloyd Kortge calmly reached out his hand and rested it on Vince’s shoulder. “Santucci, you ain't from around here, are you, boy?”In the 1980s, there were no federal laws mandating how fossils on public lands should be protected. National parks had long been places for paleontological research and academic collecting, but there were no federal guidelines or penalties identified for fossil poaching. These fossils were being unearthed from within the National Park and sold to private collectors. “It broke my heart. It truly did,” recalls Vince. It wasn’t just these irreplaceable fossils that were disappearing, but also the opportunities they provided for learning and connection. Without fossil-specific laws in place and a lack of physical barriers and signs, local prosecutors had difficulty in convicting anyone for fossil theft. The Rangers devised a plan: Vince would go undercover.

In plain clothes, Vince wandered into the same outcrop he noticed the crimes taking place. Spooked by his arrival, one collector swiftly wandered off. To his surprise, another stayed and enthusiastically greeted him. Without much probing, the collector admitted that what they were doing was illegal, but they felt they were rescuing the fossils from eroding away. At that time, fossil Inventory and Monitoring programs had not been established yet. The collector offered to let undercover Santucci peruse their collection back in town “and bring money,” they said, “because I got lots of things that you're probably going to want to buy.”

Preparing for another arm on his shoulder, Vince returned to report this latest news to Ranger Lloyd. With conviction, he told him what he had encountered in the field that day. With that intel, one of the park law enforcement rangers was able to return to the same outcrop to cite the collector. Once in court, Vince was ready for the hammer of justice to fall. The collector was honest and forthcoming to the court about their crimes. Upon conviction, the judge announced the penalty: a $50 fine. “My jaw hit the table,” Vince recalled, “and at that moment I knew that we needed to do more to protect our fossils, and from that day on, I was committed to go out and fight to get greater protective legislation for fossils.”

Courtesy Vince Santucci

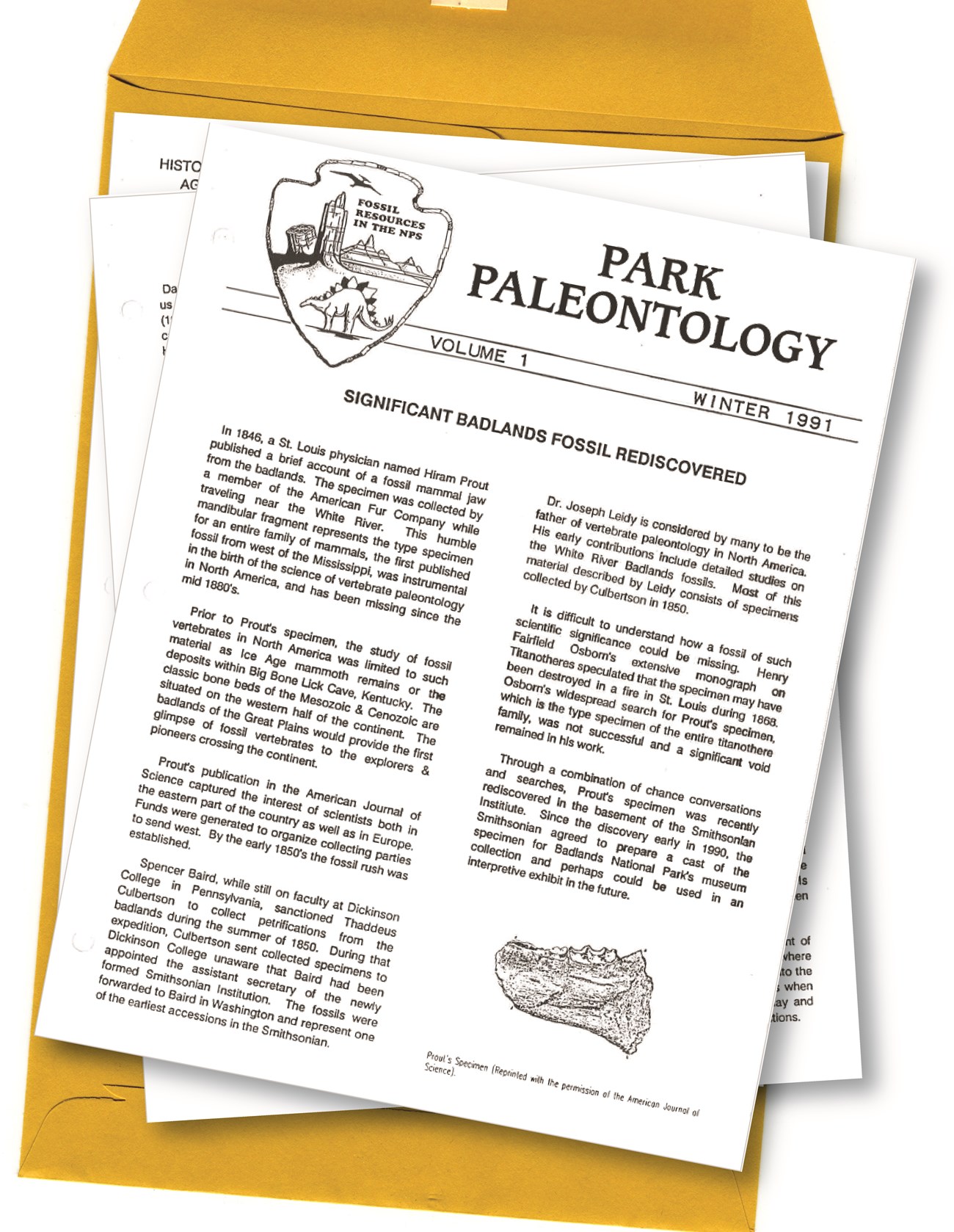

Captions for a selection of "Footnotes In Time" cartoons include: Top left: “As your attorney, I must inform you that as long as you are alive you are protected under the Endangered Species Act, but once extinct & fossilized, there will be little that anyone can do to protect you!” Top right: “Superintendent B. Crat decided not to hire a paleontologist at the park, but rather another biologist to study the adverse effects that fossils may have on the biological resources.” Bottom right: “Poached eggs!”

The Advocate

“I was incensed to the bone. I was driven,” recalls Vince. He needed to get the word out to really effect change. In his free time after work, Vince channeled his newfound passion into an unexpected medium: drawing cartoons. These “Footnotes in Time” were cut and glued to paper with articles Vince authored to draw attention to the vulnerability and value of fossils in our National Park places. The first issue of the Park Paleontology newsletter was complete. “It wasn't officially sanctioned by anybody. It was something I just felt I needed to do,” recalls Vince. He made about 120 copies and mailed them, out of his own pocket, to bureaucrats, scientists, legislators, and more. His investment ended up paying off. Vince carried the passion, perseverance, and conviction he formed as a young Ranger throughout his career. “We went to Washington,” he recalls, “we advocated. It took a long time, but everything came together serendipitously in ways that those early investments helped pay off in the long run for our agency, and that I'm very, very proud of.”Decades later, Park Paleontology News shares the triumphs and challenges of National Park Service Paleontology today. Despite his senior position within the NPS Paleontology Program, Vince is still a researcher and Ranger at heart. “Badlands sediments definitely still flow through my bloodstream,” he says fondly. “It's my first love in the National Park Service. It will always be, and I just feel so privileged to have had the opportunity to work there.”

Courtesy Vince Santucci