Last updated: February 25, 2022

Article

Flint Hills Geology

NPS Image

Introduction

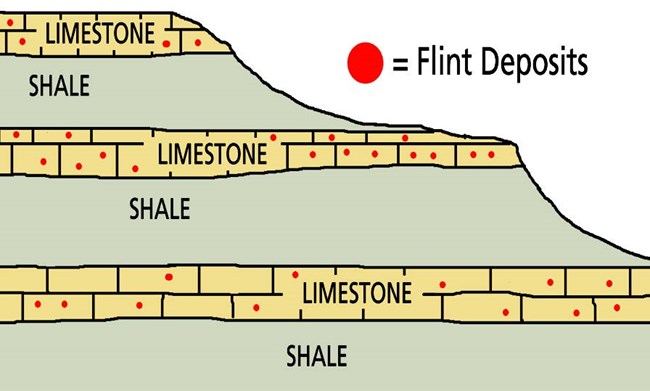

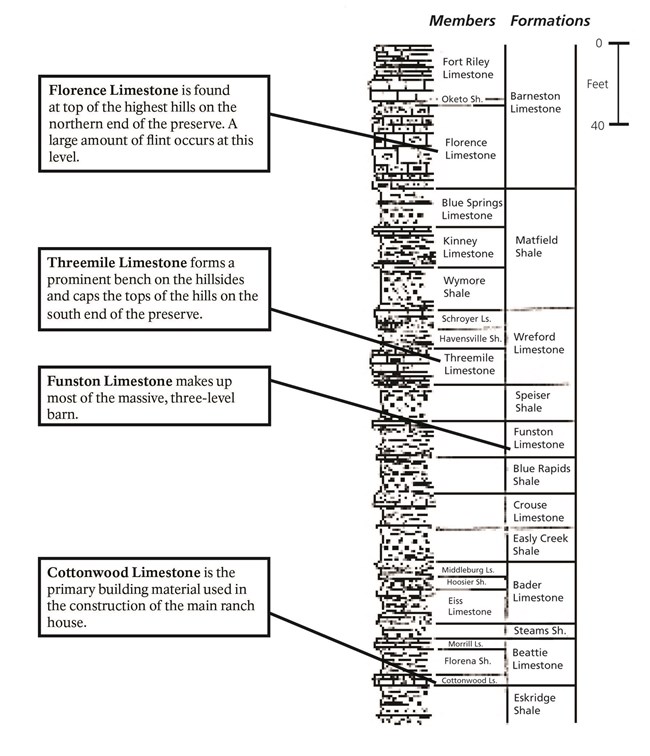

The Flint Hills cross east central Kansas from the near the Nebraska border extending south into the Osage Hills of Oklahoma. The region consists mainly of alternating layers of limestone and shale. Many of the limestones contain concentrations of chert (also called flint)—a hard, dense microcrystalline quartz. As the limestone erodes, angular fragments of flint accumulate at the surface, giving the Flint Hills their name. The native peoples of the region, the Pawnee, Osage, Wichita, and Kansa, collected the exposed flint to make a wide variety of tools and weapons.

The unique, stairstep landscape of the Flint Hills formed through a geological process called differential erosion. The limestone, with concentrations of flint, resists erosion more than the softer layers of shale in between. The tougher limestones and flint form prominent benches on the hillsides and cap the hilltops. The softer shale in between are slowly worn away, making thin, gravelly soil. These rolling hillsides and rocky soil saved the Flint Hills from wide-scale plowing and helped to preserve more native tallgrass prairie here than anywhere else in North America.

Kansas Geological Survey

Abundant Fossils

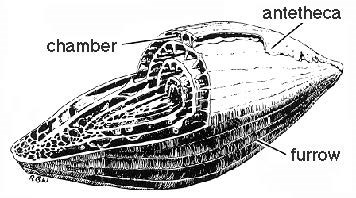

A closer look at the rock reveals many fossils. Most of these marine fossils are invertebrates (animals without backbones) such as corals, clams, snails, bryozoans (colonies of animals resembling sea fans), sea urchins, crinoids (a stalked animal distantly related to starfish and sea urchins), and clam-like animals called brachiopods. Particularly abundant in some limestones are fusulinids, small, one-celled animals shaped like wheat grains. These fossils can be seen in many of the limestone blocks used in the buildings at the preserve.

NPS Photo

Geology, Soil, and Land Use

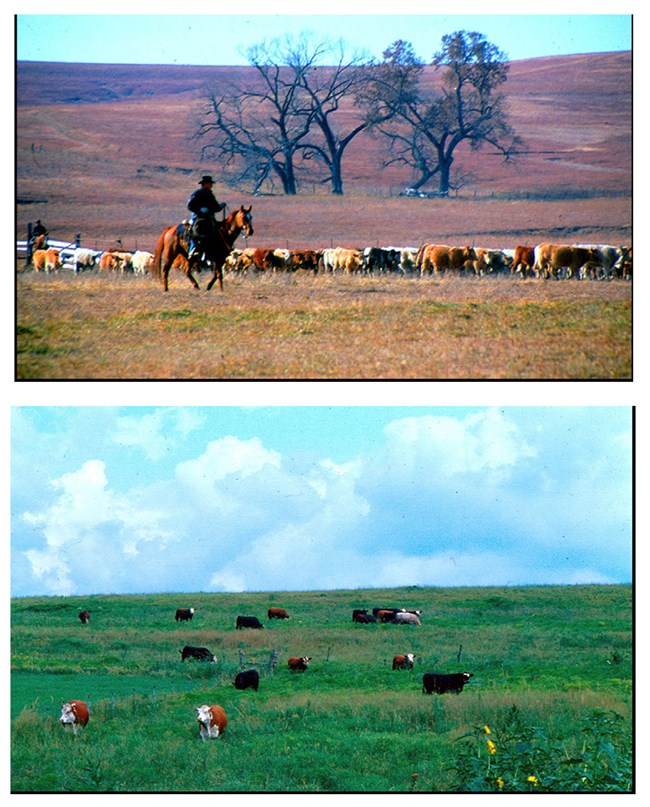

The Flint Hills region is characterized by thin soils, limestone outcrops, vegetation-covered shale intervals between the limestones, and deeply cut valleys, exposing the geology beneath the soil. The thin, rocky soils and steep slopes of the Flint Hills limited crop cultivation to river and stream bottoms, such as along Fox Creek just east of the historic ranch headquarters area. These rare bottomland prairie areas are covered by a layer of river-deposited sediments that have developed thick soils that are especially valuable for cultivation.

However, the same rocks which made crop cultivation difficult helped to preserve the native characteristics of the Flint Hills and made the area ideal for cattle grazing. The calcium in the limestone, in fact, erodes into the soil, making the native prairie plants extra nutritious for grazing animals. Cattle ranching remains the dominant agricultural activity in the Flint Hills, with a legacy of cattle ranching extending back for over 150 years in the region.

NPS Photo

Building with limestone

Wood was scarce when European-American settlers came to the Flint Hills in the mid-1800s, so the abundant limestone became an important source of building material. The Cottonwood Limestone, a rock layer that occurs on the preserve near the base of the hills in the Fox Creek valley, is a common building stone in Kansas. It is a thick layer of limestone, nearly white in color, even-textured, durable, and contains numerous fusulinids. Blocks of stone three or more feet thick and several feet in length and width can be taken from a single ledge.

The Ranch House, portions of the Lower Fox Creek Schoolhouse and Ranch Barn, and many other structures on the preserve were built with this type of limestone, as well as numerous buildings in the state, including the Chase County Courthouse in Cottonwood Falls, and most of the Kansas State Capitol building in Topeka.

Formation of rocks at the preserve

The Flint Hills alternate layers of limestone (with flint) and shale deposited during the Permian Period, around 280 million years ago. A shallow ocean covered the surface most of this tropical geologic period of warmer climate. As marine organisms rich in calcium fell to the bottom of this ocean their remains became stone (lithification). Clay and mud deposited on the ocean floor lithified into shale.

Chert (flint) can occur within limestone as roughly spherical concentrations (nodules) or as layers (laminated). Some geologists believe the nodules of chert may have formed from the remains of marine organisms rich in silica. The remains fell to the ocean floor, then migrated together as the limestone formed. The layers of chert may have formed as the silica material recrystallized, chemically replacing the limestone. Geologists continue to conduct research and study into these processes.

Kansas Geological Survey

Classification of rocks at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve

The rock layers are named after the towns, streams, or other nearby landmarks where each rock layer was first found and described by geologists.