Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 099: Finding and Preserving LGBTQ Southern History with the Invisible Histories Project

Invisible Histories Project

Invisible Histories Project

Catherine Cooper: What is the Invisible Histories Project and how did you come to start it?

Maigen Sullivan: We are a 501C3 non-profit. We’re not a traditional archive or a traditional education, but our main focus is LGBTQ history and archiving. We act as an intermediary between organizations like museums and libraries and universities and LGBTQ people in the south. So, we’re trying to connect folks and locate histories in order to get them preserved and researched. So that’s basically what we do.

It’s a little unusual, there’s not a lot of folks doing that because we don’t actually have that kind of physical archives space and we’re not a university, but we act between them in order to preserve that history in Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia as of March this year.

Best Practices: Preservation, Accessibility

And we also manage a network of archivists, historians, just people interested in queer and trans southern history. It’s called Queer History South, which is a conference where we get together, and we just talk about best practices. How do we find this history? How do we preserve it and how do we make it accessible?

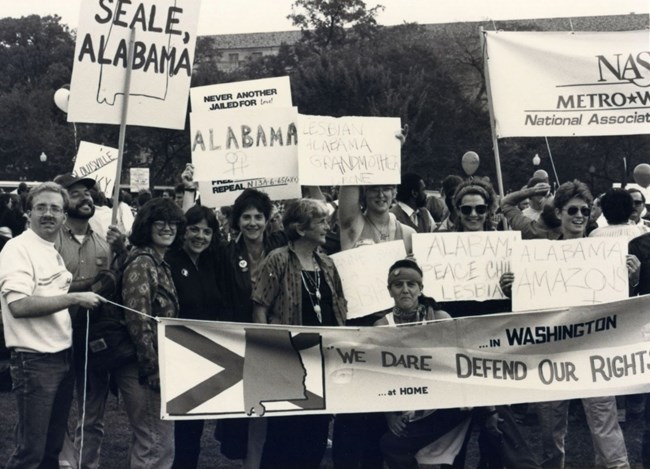

Invisible Histories Project

Josh Burford: I think how we got started is very typically a queer story in that there was this gap. We were looking for information about our own history. We were being asked information about our own history and we didn’t have access to it. It wasn’t in traditional repositories, it wasn’t in libraries, it wasn’t being studied at universities and so, we took it upon ourselves to do what a lot of southern queer people have done, which is grass roots organize to locate and preserve our own history.

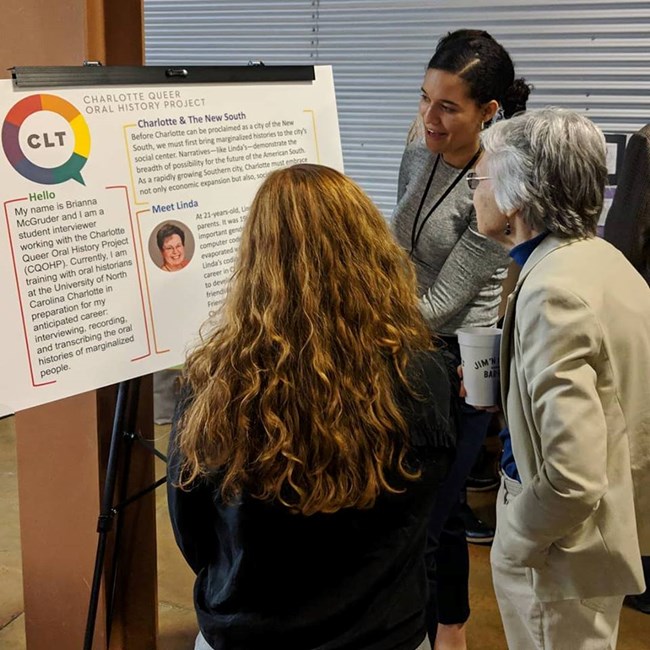

The nice thing is Maigen and I have both been in higher ed in the past. We understand how it works. I moved to Charlotte in 2012 to build an archive for the city of Charlotte—an LGBT archive—and so, while I was there, Maigen and I talked about the possibility of taking this city-wide project and turning it into a state-wide project in Alabama. Since we’re both from Alabama and both from the deep south, it made sense that that’s where we would start.

And now we’re a regional project within in two years. There’s just so much material that needs to be collected. We’ve collected sixty-three individual LGBT collections in Alabama in the last eighteen months.

We’re on track to double that number in the next two years and we’re on track to have collections that wide and in that much scope in Mississippi and Georgia. We’ll be at five hundred, six hundred collections in three states in four years.

Invisible Histories Project

Materials Collection

Catherine Cooper: What materials does the project seek to collect and are you actively looking for these collections?

Josh Burford: Yes, we are actively collecting and so if you can imagine a spreadsheet in your head for a second, you know there is a whole section that’s just stuff we’ve already collected with all the data.

There’s a section of collections that have started but we haven’t picked up materials. So, that list is probably around seventy or eighty individuals and groups. So that we’ve contacted them and then we’re working with them.

And then we have our research collections. I mean, the one from Georgia has gotten so big, so quickly and we’ve only really been officially in Georgia since March.

Donors Central to Preserving Our History

So, we are working with donors every single day. I mean I was on the phone with donors this morning, I have donor meetings the rest of the week and even though we’re distancing, you know we’re looking for ways to continue the process.

Invisible Histories Project

Every single donation that we pick up—and I think this is part of the benefit of doing a grass roots-based project—is that I see every donation that we pick up as access to fifteen or twenty additional donors and donations. Because we are asking people when we pick up their materials, who influenced you? Who were your people? Who was your community? And so, the work quickly fans out especially because of the connectivity between Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia. There’s so much shared history there.

As far as what we’re collecting, I mean it would probably be easier to list what we’re not collecting at this point. But you know, the traditional manuscript collections, so letters, photos, documents related to organizations, meeting minutes, posters, flyers, the usual stuff that you’d see in an archive. But because, to make Maigen’s point, we’re not a traditional archival repository, a lot of 3D collections; so, dresses, drag performance gowns, Mardi Gras textiles, banners from gay pride festivals, we’ve got the very first disco ball from a gay bar in Tuscaloosa, which is in our office currently.

Maigen Sullivan: The good thing about us, is because we’re really focusing on community accessibility, that’s our number one goal for materials. So, we have a number of repositories that we work with and these are both local, state repositories as well as some national partners that we negotiate what that will look like and then we can work with the donors to get their materials to the right place.

Ideally, something would stay local, so if it came from Birmingham, Alabama, it would go to Birmingham Public Library. However, everyone has restrictions on what they can take and size and specialty, so if there are pieces, we do like to keep things together, but let’s say that there’s a really critical piece like a disco ball, that can’t just be stored anywhere, we will find the repository that is invested in storing that kind of material in order to make sure that it’s the right fit for the archive as well as the donor.

Process of Housing and Preserving

Catherine Cooper: So that actually very much speaks to the next question which is, what is your process for housing and preserving and it’s these partnerships…

Josh Burford: Yeah, and I think the layer that we have that a lot of traditional archival repositories don’t have, is that we have integrated social media into our work. We also have amazing archival repository partners, so if we get a piece in and it’s in really bad shape or it’s like Maigen’s point, like a disco ball, like where’s that going to go? We have a network of people we can reach out to immediately and find out.

So, we’re not saying no to collections right away, but we get the chance to bring collections in to IHP, to do what we call a pre-sort. So, we’re able to organize the materials as they come. So, it doesn’t matter what shape they’re in. We work with the donor and then we get it figured out.

Invisible Histories Project

Then we get to take photos of material, we put that on our social media. We get to look at what the collections are about and then start building lists of individual people we want to work on the collections because we’ve got this huge network.

I think, if things had been different in our world at the moment, this summer we would have had four different graduate and undergraduate students in Alabama, all working on a different collections.

So, we’re pushing the material out, we want people to see it and handle it and to look at it and to photograph it and to write about it and to experience it. So, for us, the preservation piece is very crucial so that people can see it from now and a hundred years from now.

But Maigen is right, accessibility is at the top of our list because as we’re very fond of saying, the difference between archiving and hoarding is a very important distinction to make. It’s not enough to have it in a box. It’s not enough that it’s safe. It needs to be available to the public.

Maigen Sullivan: We also provide support for the repositories and the universities that we work with. So, you know you’ve got all this stuff coming in, sixty collections really fast, that is very overwhelming. So, what we like to try to do is give this information up front; this is what’s in this collection. We’ve worked with the donor, they understand what is and what isn’t archivable. We’ve gone through and cleaned things up and then we work with universities in the three states that were to bring in graduate archival students that will help fully process. You know, write up the finding aids, organize everything, help store it and then give everything to us, so we can connect with researchers, either on student level or a faculty level who want to come in and research the material and get that out into the public as well.

So, we’re helping a lot of these folks get the things that we donate to them ready for research and accessibility pretty quickly because these students are, they’re killing it. They come in and they’re like, boom, boom, boom, forty boxes, what’s that?

Josh Burford: It’s also nice to be able to plan for the future of individual materials that we’re getting. We get requests all the time for things like LGBT identity and southern religions, or lesbian history. As we’re bringing collections in, we already have a working list of people that we can reach out to, even before we’ve picked up the actual boxes and say, “Hey, I want you to know that this is coming.”

Because of that we’ve been able to build coursework at so many of our institutional university partners so that undergraduates are working with primary documents. They’re digitizing for us. They’re describing collections, they’re creating subject headings for search.

Access to Collections

Catherine Cooper: So, for people who are looking for getting access to these collections, what do you recommend?

Josh Burford: Well I think the easiest place to start is our website (Invisible Histories Project), which just went through a facelift and so it’s really beautiful and people should look at it, InvisibleHistory.org. It’s a good place to start because we’re listing out our institutional partners and our collections by state. If they follow us on social media at all, they’ll be able to see the collections literally as they arrive on our doorstep.

And then, we push people to our repositories so that they can make the initial contact. Anybody that were working with, if you pick up the phone and say, “I’m looking for this collection, IHP brought it to you,” they can get it to you.

Invisible Histories Project

Maigen Sullivan: We are on Instagram and Facebook the most, we’re at Invisible Histories Project on both of those. We are technically on Twitter, but we are not great at Twitter, but you can find things there.

Another thing too, if people are looking for something, if they’re interested, if they’re doing a project or if they have materials that they want to donate, we get a ton of hits on social media, they’re like, “Hey, I have this 1940’s piece, is this good?” They can email us at contact@invisiblehistory.org [contact form], and we can work with folks to figure out what would be best, particularly with everything being so weird right now, trying to get them access to the materials is going to be a little tricky because like Josh said, most of the stuff isn’t digitized right now at least.

Catherine Cooper: What are the ways you’ve been able to use these collections in your education programs?

Education Programs

Maigen Sullivan: We do a lot of talks, we do a lot of presentations, we have worked with queer youth centers and we have a traveling mini exhibit that represents mostly Alabama right now, but also Mississippi and Georgia.

The biggest thing was in the beginning, well even now, this material was not widely available. It wasn’t collected and if it was, it was oftentimes hidden under weird headings or unacknowledged or not processed. So, we have spent, at the beginning time, just getting the materials, just finding them and bringing them in. We are now to a place where we can do more education.

Josh Burford: And we’re not starting from scratch, because obviously there have been queer historians before, but because we’re new and because people know who we are now, at least on some level, we’re able to try different things that maybe people haven’t done before. So, we launched a digital project called, Drag Family Trees and so we’re having drag queens literally, physically map out their drag families for us, like their drag mothers and siblings are. And then at a certain point coalescing all that material together so that you cannot just see the evolution of an individual drag queen but all the connectivity between all of the deep south states. I mean there’s so much connectivity between Atlanta, Birmingham, Jackson, Mississippi and New Orleans, just in that I-20 corridor. And anytime we can get primary documents in the hands of undergraduates, I’m delighted.

Maigen Sullivan: So, we’re working with organizations and individuals who are involved in some sort of queer organizing or movement, to archive what they’re doing right now. So, we come in yearly with different organizations, different individuals, we say, “Okay, what do you got from this year,” so that we can create plans that we can go ahead and integrate, with things from the 1920’s, with things from the turn of the century, with stuff from the 2000’s, so that young folks can understand that you’re a part of history and that all of these actions that you take, add up and matter at some point. And I think that’s been really great to see as we’ve worked with folks.

Catherine Cooper: For people who want to get involved both now and when we’re allowed to meet in person again, what would you recommend?

Maigen Sullivan: The first thing is to follow us on the social medias, check out the website, email us at the contact Invisible History. If you’ve got questions, we do have a few ways for people to get involved. All of the archives that we work with are shutdown.

So, we can’t keep producing social media posts like we used to, so if folks have queer southern photos that they would like to share with us, we would love to get them, to feature them online. We’ve started a[n Invisible Histories Project] YouTube series, where we sit down and talk with different folks doing queer history work across the country or who are involved in queer organizing. So that’s available if folks want to just see what people are doing and ways that they can get involved outside of IHP. Just shoot us and email if you’re interested and we’ll figure things out.

Josh Burford: Something else that we want people to know about is that we’ve launched a new program called, Archiving at Home, which now has a tab on our website. You can click on it. Basically, it is a step by step explanation of the process; how you go from a closet full of materials to an archivable collection step by step. It explains both, what kind of materials we’re looking for, how you should be putting things together, etcetera. It also explains digital documents, so like what you can do for digitization. If you have digital clouds, how we preserve those.

People can download the PDF, they can start working on it and if folks live near us in Birmingham, Jefferson or Shelby county, you will actually physically take them boxes and so, they can have boxes on their front door safely and start putting stuff away, which we really appreciate.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.