Last updated: November 28, 2022

Article

Financial Ruin at White Haven: The Panic of 1857 Comes to White Haven

Library of Congress

The December holidays can be a stressful time for families trying to provide the best holiday experience for their loved ones. Money can be tight, causing people to find creative means to earn more money to purchase gifts for loved ones. Ulysses S. Grant was no exception and found himself in tough times during a Christmas season while living at White Haven. On December 23, 1857, two days before Christmas, the thirty-five-year-old ex-army officer, farmer, and father of three (with one more on the way) walked into the pawn store of J. S. Freligh to pawn off an important “gold hunting [watch] detached lever and gold chain.” He authorized Freligh to sell the watch and chain at public or private sale. Although there is strong speculation that Grant pawned these items two days before Christmas to receive badly needed money to provide his family with a “happy Christmas,” there is no solid historical proof of the exact reason. What is known is that he pawned this possession off to earn extra money for himself. A main reason why Grant and many other Americans were having a very uncertain Christmas that year was the Panic of 1857.

The Panic of 1857 grew out a period of great growth in the United States. The continuing “Industrial Revolution” throughout the 1850s rapidly grew the US economy. According to historian James M. McPherson, there were several reasons to explain this economic growth. Examples include new banks increasing throughout the country, which increased banknote circulation; railroad mileage and capital tripled from 1850-57; textile mills, foundries, factories greatly increased production, as well as cotton and the growth of slavery in the south; finally, gold from the California Gold Rush pumped money into the US economy. The US economy was intertwined with that of certain European countries, particularly Britain and France. A great amount of wealth invested in American railroads, banks, and industrial factories came from these two countries. While European investments fueled U.S. economic growth in the early 1850s, warning signs began to emerge. From 1853 to 1856, the Crimean War occurred between Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire against Russia along the Crimean Peninsula. The French and British also heavily invested in colonial ventures in Asia during this time. These investments drained European banks of capital, causing investors to sell their American securities to invest elsewhere. By 1857, the value of American stocks and bonds began to decline, as did the capital assets held by American banks.

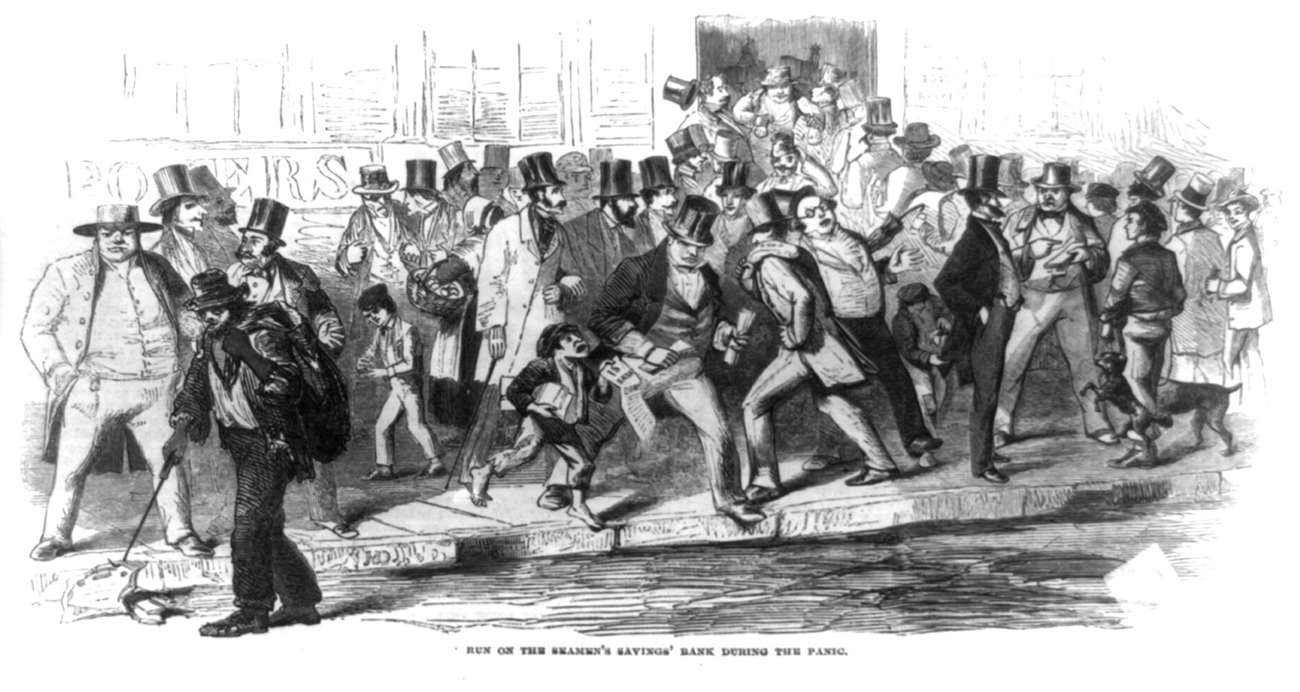

The actual trigger that brought on the Panic of 1857 took place on August 24 when a New York division of an Ohio Investment house ceased payments because “the cashier had embezzled its funds.” This meant that one of the nation’s largest banking firms couldn’t pay its investors. This caused a loss of confidence and set off a chain reaction which reverberated through the economy. As financial markets were interconnected by the telegraph, this reaction spread across the U.S. Banks called in loans to increase their money deposits, while investors panicked and did just the opposite by trying to cash out their savings before the banks went out of business. This is the reason why the economic recession of 1857 is called a “Panic” by historians. Additionally, the SS Central America, which aimed to ship 2 million dollars of California gold to replenish depleted funds in the east, sank in a hurricane. This tragedy caused not just the loss of all the gold on board, but also the lives of 425 out of 578 people on board. The Panic created business and factory failures, railroads went bankrupt, and most concerning to the White Haven farmer, Ulysses S. Grant, crop prices fell.

Amid the economic uncertainty, Ulysses S. Grant did his best to support his growing family by living and farming at White Haven, which was owned by his father-in-law. Although Ulysses seemed to enjoy farming, it was a struggle to be successful. He wrote his father Jesse in February 1857, “Spring is now approaching when farmers require not only to till the soil, but to have the wherewith to till it, and to seed it. For two years I have been compelled to farm without either of these facilities, confining my attention therefore principally to oats and corn: two crops which can never pay…I want to vary the crop a little and to have implements to cultivate with.” Grant then asked his father for a loan of five-hundred dollars for two years with interest at ten percent payable either annually or semiannually. He told his father, “It is always usual for parents to give their children assistance in beginning life (and I am only beginning though thirty five years of age, nearly.”)

From all available sources, there is no evidence to verify that Jesse Grant gave his son the loan. Yet in a letter to his sister Mary on August 22, 1857, around the same time the panic began, Grant remained optimistic writing her, “My hard work is now over for the season with a fair prospect of being remunerated in everything but the wheat.” He told her that his oat crop was “good” and his corn, “if not injured by the frost this fall, will be the best I ever raised.” He also raised potatoes, sweet potatoes, melons, and cabbages for sale at local markets. Despite his optimism, farming was not profitable for Grant in 1857. Just two days before Christmas, Grant chose to pawn off his valuable gold watch and chain. Grant reeled from the effects of the Panic of 1857. Despite the rather bleak Christmas, Ulysses and Julia soon received a gift of their own with the birth of their fourth child, Jesse, in February. Grant would continue to farm throughout much of 1858, but by the fall he moved to St. Louis. He eventually secured a job with Harry Boggs, a cousin of his wife Julia, in the real estate business. While Grant was not financially successful with farming, within a few years his fortunes dramatically changed with the coming of the American Civil War.

Grant’s pawn ticket was kept by J.S. Freligh’s nephew, Louis H. Freligh for fifty-three years. On March 19, 1910, Freligh tried to sell the document to an autograph dealer, W. R. Benjamin. He wrote, “I can attest to its authenticity, as I was present at the transaction, & saw him sign his name to the document. I am now 71 and ½ years old, so as I was then less than 20, can very well remember it.” He claimed the reason he waited this long to sell it was because, “so many people consider it a disgrace to patronize ‘mine uncle’ and I did not wish to give offense to the renowned general’s family by exposing the matter.” He then told the dealer that if he didn’t buy it to “kindly keep it quiet.”

As for the Panic of 1857, it was short lived. The economy began strengthening again by the Spring of 1858. Bank and specie improvements were discussed. Inflation was temporarily brought down, and gold shipments from California resumed. American manufacturing and industrial interests proposed raising a “protective” tariff on imported goods. However, many agricultural and southern planter interests were against it. The Panic caused distrust and blame between powerful slaveholding southern interests and northern manufacturing and industrial interests. The economic crises further divided the United States sectionally and created more tension over the institution of slavery just a few years before the start of the American Civil War in 1861.

Further Reading

James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press,1988. pg 188-92.

John Y. Simon, ed. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Volume 1: 1837-1861. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967. Pg. 156-158

Kenneth M. Stampp. America in 1857 A Nation on the Brink. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. Pg. 213-239.