Part of a series of articles titled The National Archives as a National Historic Landmark.

Article

Federal Architecture: Private Architects and Public Projects

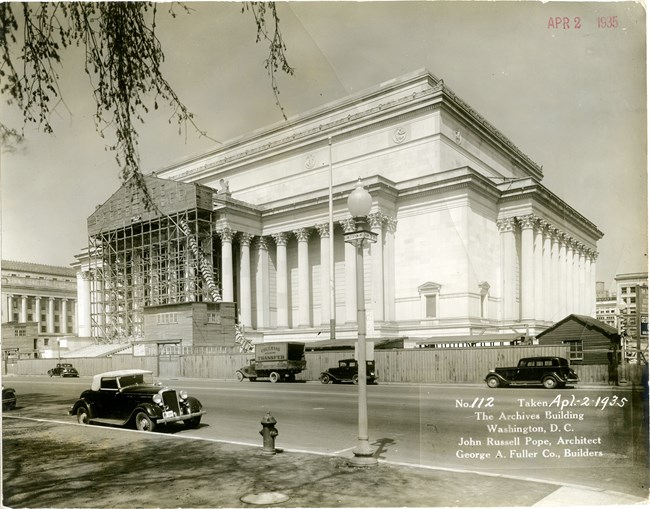

NATIONAL ARCHIVES / NAID: 79443934.

When the National Archives building was designed in 1931, many federal buildings were designed by government architects. However, the project to construct the National Archives, as well as the surrounding Federal Triangle, was seen as important enough and large enough to warrant the creation of a Board of Architectural Consultants to guide its design. The board was made up of private architects tasked with designing federal buildings. Their involvement marked a change in the government’s policy toward the use of private architects for public projects in the early 1900s.

Legislation to Include Private Architects

While private architects compete for the designs of most public building projects today, prior to the Tarsney Act (1893) public buildings were often designed and constructed by federal architects or sometimes by private architects directly commissioned by the Secretary of the Treasury. When it was passed, the Tarsney Act allowed up to five private architects to compete for federal projects, the objective being that private architects would bring “the grandeur of European public buildings” to the United States.1 The bill was largely popular in the architectural world, though some government officials were cautious of its implementation. Concerns over budgets and funding were combined with caution over changing the traditional structure of the Office of the Supervising Architect (OSA) and how it functioned. Despite this, the Tarsney Act passed, though it was later repealed in 1912 due to the associated costs of holding design competitions as well corruption and mismanagement of funds from the OSA.2

Following the repeal of the Tarsney Act, government projects returned exclusively to the domain of federal architects and private architects were excluded. However, the tide turned again in 1926 with passage of the Public Buildings Act. This legislation gave the Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew Mellon, the ability to hire private architects to make federal construction projects more efficient, differing from the function of the Tarsney Act but still promoting the inclusion of private architects. This legislation came at an opportune time for American architects and helped to reinvigorate the profession.3

NATIONAL ARCHIVES / NAID: 7851119.

New Opportunities for Architects

When the Public Buildings Act was enacted in 1926, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) was a well-established organization of professional architects. The function of the institution was (and is today) to promote the profession as well as emphasize the importance of architecture and design in American life. In fact, the organization had been involved with lobbying for the Tarsney Act (1893) and were eager for AIA members to again have the opportunity to work on public projects following its 1912 repeal. The design of the Federal Triangle was considered one of the most expansive government building projects to date. The AIA argued that government architects were not able to develop appropriately monumental designs for such an important project.

In 1927, after lobbying the Office of the Supervising Architect (OSA), AIA succeeded in convincing the Treasury Secretary to involve architects of national reputation in the Federal Triangle design.

According to Louis A. Simon, one of the highest-ranking architects in the OSA, “the first intention [of the Federal Triangle project] was to construct a few Federal buildings, regarded at that time as unrelated.”4 However, by 1928 the objective of the project changed when the Secretary of the Treasury acquired the entire triangle area. This land acquisition was achieved through a combination of purchasing privately owned land parcels and enforcing a 1926 condemnation statute, essentially forcing private owners to relinquish ownership to the government through eminent domain. The consolidation of land allowed for a more cohesive design of buildings.5 A Board of Architectural Consultants was created, made up of prominent private architects, with each member overseeing the design and construction of individual buildings within the triangle project. Ultimately, the decision to include private architects in the design process was a great success for the AIA, as they saw this as an opportunity for the consistent inclusion of private architects on public projects.6

The development of the Federal Triangle plan

Left image

A cropped section of the 1905 map of Washington, DC from the "Standard guide."

Credit: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / FOSTER & REYNOLDS

Right image

A cropped section of a 1930 proposal for the Federal Triangle, "The Mall and vicinity, Washington, proposed development."

Credit: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / PUBLIC BUILDINGS COMMISSION

Federal Architecture Today

Today, federal building projects continue to be open to private architects. The Public Building Service (PBS), under the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), contracts with private-sector architects and engineers to design, modernize existing, and construct new federal buildings throughout the nation.

The design and construction of the Federal Triangle, including the National Archives, was a large-scale demonstration of public-private collaborations between the federal government and private architects that continues to this day.

Endnotes:

- Quote from the New York Commercial Advertiser (1893) found in Antoinette Lee, Architects to the Nation: The Rise and Decline of the Office of the Supervising Architect, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 168.

- Lee, Architects to the Nation, 166-8.

- Ibid, 239.

- Ibid, 242.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 244.

References:

Bedford, Steven. National Archvies Building. National Historic Landmark nomination form. Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2022.

Lee, Antoinette. Architects to the Nation: The Rise and Decline of the Office of the Supervising Architect. New York: Oxford University Press. 2000.

U.S. General Services Administration. “A Timeline of Architecture and Government.” GSA. August 8, 2017. A Timeline of Architecture and Government | GSA.

———. “PBS Office of Design and Construction.” Data to Decisions. Accessed August 24, 2023. PBS Office of Design and Construction (PC) | D2D (gsa.gov).

Tags

- national historic landmark

- national archives

- archives

- archive

- federal triangle

- supervising architect of the treasury

- architecture

- architects

- john russell pope

- andrew mellon

- public building service

- public building act

- american institute of architects

- pennsylvania avenue

- national capital region

- ncr

- nhl

- history

Last updated: October 10, 2024