Last updated: July 19, 2024

Article

FDR, Wheelchairs, and Diplomacy

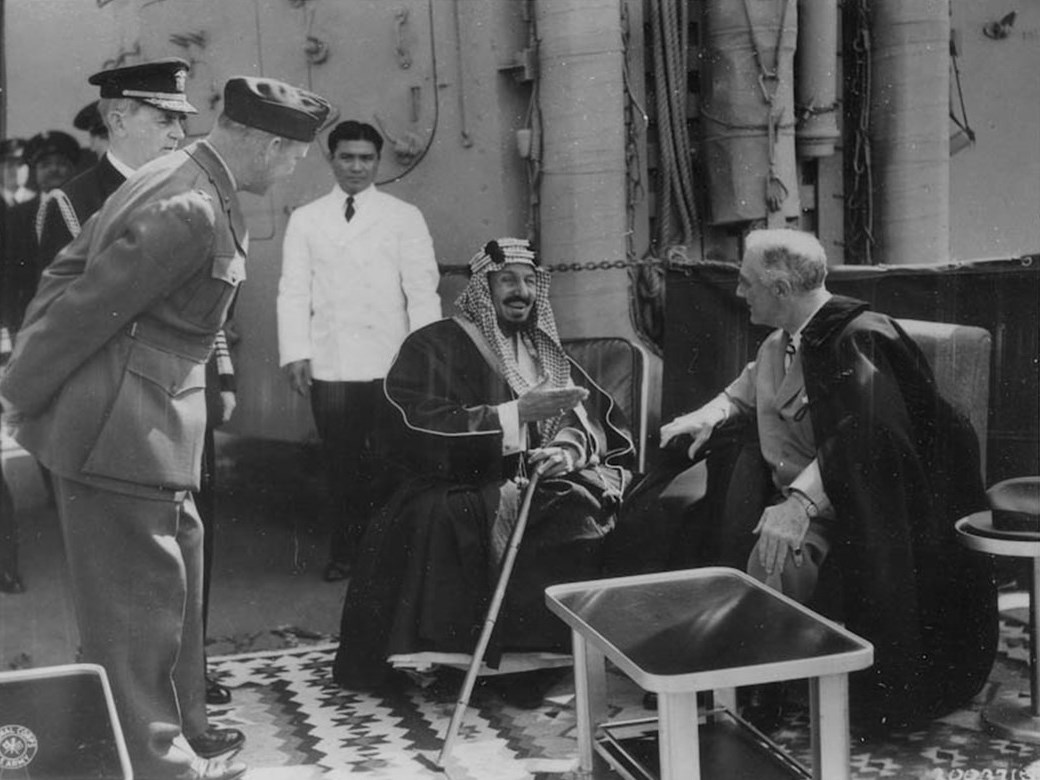

Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

With the end of World War II in sight, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Sir Winston Churchill, and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, in February of 1945. The “Big Three” met at Yalta to discuss the reorganization of the European geopolitical landscape after the inevitable fall of Nazi Germany, Soviet involvement in the Pacific Theatre of the war against the Empire of Japan, and the framework of the United Nations.

After the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, President Roosevelt met with several Middle Eastern heads of state along his voyage back to the United States, including King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia on February 14, 1945. The two leaders met aboard the USS Quincy, while the destroyer passed through the Suez Canal. During their conference, the President and the King discussed political challenges faced by Middle Eastern nations, such as the settlement of European Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Palestine, European colonialism in the Middle East and the struggle for sovereignty, and efforts to increase agriculture through improved irrigation in the region.1

Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Newspaper and State Department accounts of the meeting indicate that the two heads of state opened a productive dialogue and shared warm, friendly feelings during a very successful audience. The leaders also exchanged gifts as a sign of good faith and mutual respect before their summit. Suad presented the American president with a jewel-encrusted saber, fine perfumes and musks, a piece of rare ambergris, and beautiful examples of traditional Arab clothing. President Roosevelt’s remarkable gift to King Saud did not go unnoticed by the press.

William Eddy, the American Minister to Saudi Arabia, was instrumental in arranging the meeting and acted as a translator for the President. In a letter to the Secretary of State, Eddy recorded the friendly nature of the discussion and, specifically, the presentation of the President's gift to the King:

During the more informal visit on deck before lunch (11:30 to 1:00 p.m., February 14) a very friendly relationship was quickly established. The King spoke of being the “twin” brother of the President, in years, in responsibility as Chief of State, and in physical disability. The President said, “but you are fortunate to still have the use of your legs to take you wherever you choose to go.” The King replied, “It is you, Mr. President, who are fortunate. My legs grow feebler every year; with your more reliable wheel-chair you are assured that you will arrive.” The President then said, “I have two of these chairs, which are also twins. Would you accept one as a personal gift from me?” The King said, “Gratefully. I shall use it daily and always recall affectionately the giver, my great and good friend.2

The personal backgrounds and common interests of the two leaders brought them close together. But it was their shared experiences with disability and the offering of the wheelchair that cemented their fast friendship. Eddy again recalled the exchange, in greater detail, in an account published in 1954:

The King and the President got along famously together. Among many passes of pleasant conversation I shall choose the King’s stamen to the President that the two of them really were twins: (1) that were both of the same age (which was not quite correct); (2) they were both heads of states with grave responsibilities to defend, protect and feed their people; (3) they were both at heart farmer, the President having made quite a hit with the King by emphasizing his rural responsibilities as the squire of Hyde Park and his interest in agriculture; (4) they both bore in their bodies grave physical infirmities – the President obliged to move in a chair and the King walking with difficulty and unable to climb stairs because of wounds in his legs… Whenever the King took friends through his palace at Riyadh, if there were close friends, he showed them his private apartment where his wheelchair rested with the White House tag still on it. The King always said, “This chair is my most precious possession. It is the gift of my great and good friend, President Roosevelt, on whom Allah has had mercy.” The King who later used a wheelchair, did not use thus gift chair which was built for the very slight and frail F.D.R. and could never be used by the King, a man of terrific physique and stature.3

ArabNews image.

Shortly after his summit with President Roosevelt, King Saud also met with Prime Minister Winston Churchill to discuss similar issues about the future of the Middle East. However, King Saud and Churchill didn’t share the same amiable meeting that Saud had experienced with President Roosevelt. The British attempted to outshine the Americans with a larger ship and a grander display, which Saud apparently found “dull” and off-putting.4 He preferred the more engaging and intimate atmosphere provided by his American hosts and President Roosevelt. King Saud, by all accounts, was extremely touched by FDR’s present of his own wheelchair. President Roosevelt also valued his encounter with King Saud and found their conversation to be productive. During an address to Congress, FDR reported that he “learned more about [the Near East] by talking with Ibn Saud for five minutes than I could have learned in an exchange of two or three dozen letters.”5

Regarding this groundbreaking gift, one newspaper printed: “A new disclosure today was that the President gave King Ibn Saud a wheel chair the King had coveted. It was probably the first such gift in history between two chiefs of state.”6 By exhibiting this cherished souvenir, his "most precious possession," prominently in his private apartment in Riyadh and sharing the story to his closest friends, King Saud literally put his personal affection, admiration, and gratitude towards Roosevelt on display.

The State Department also notes that the wheelchair that President Roosevelt gave to King Saud was too small, “and the President requested Mrs. Roosevelt to arrange for a shipment of a new one to the King. This was done in August 1945.”7

Documentation in the archives of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library further confirms Eddy’s and newspaper reports. According to page 46 of the log of the USS Quincy trip to Crimea, “the President presented the King a gold Fourth-Term Inaugural Medallion (with special leather case) and also one of his wheel-chairs which had attracted the King’s fancy.”

Upon the President's return to the US from his whirlwind diplomatic tour, FDR addressed Congress for the final time on March 1, 1945. During his speech, the President reported on the success of the Yalta Conference, his encounters with Middle Eastern leaders, the nearing end of the war in Europe, and his goals for lasting world peace through the United Nations. Unlike his previous appearances before Congress, this time there was no ramp with handrails leading to the rostrum for Roosevelt to walk to the podium; instead, President Roosevelt entered the chamber of the House of Representatives in his wheelchair and remained seated for the duration of his speech. FDR apologized to the assembly:

I hope that you will pardon me for the unusual posture of sitting down during the presentation of what I want to say, but I know that you will realize that it makes it a lot easier for me in not having to carry about ten pounds of steel 'round, on the bottom of my legs; and also because of the fact that I have just completed a fourteen-thousand-mile trip.8

Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

One pundit, Jack Stinnett, questioned the President's actions in the days following the Yalta conference, which, according to Stinnett, went against the media's previous cooperation with a White House restriction on covering the President's paralysis and disability:

For more than 12 years, without any specific taboos, there has been an understanding that no stories or pictures would be circulated playing on Mr. Roosevelt’s infirmity.

Why then suddenly, has he approved the release of such stories as that from the Mediterranean when he gave Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia a wheel chair like his own? Why has he so far dropped the veil as to apologize in what may have been his most widely circulated public address before Congress the other day for remaining seated and explaining that its was easier, because to stand, he had to carry ten pounds of painful steel braces on the lower part of his legs?9

Stinnett reported rumors that FDR now acknowledged his disability only because he had no further plans to run for reelection:

The answer, say friends and political associates, is that the President is through with running for office and even with any further personal participation in politics other than perhaps giving his nod to some one who may seek to succeed him.10

Speculation that President Roosevelt no longer concealed his disability because he was free from electoral repercussions incorrectly implies that Americans were unwilling to vote a disabled person into public office.

But the American public had been aware of the President’s limited mobility. Hundreds of disabled Americans wrote letters to the President, many mailed canes to the White House, funds were raised for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (later the March of Dimes) in FDR’s name, and in 1933, more than $22,000 was donated to a campaign led by 42 newspapers to construct a swimming pool in the West Wing for the newly inaugurated Roosevelt because “Swimming in a warm water pool has been highly beneficial to Mr. Roosevelt, in his struggles with physical handicaps.”11 Stinnett couldn’t have addressed it more plainly: “It wasn’t any secret. . . . No one who could read or hear was unaware that the President had been paralyzed in the lower part of his legs by infantile paralysis.”12 During the 1932 campaign, the press scrutinized FDR’s disability to evaluate his fitness for office. Yet, with the facts of his disability laid before them, American voters still elected FDR for two terms as governor of New York and a record-setting four terms in the White House, putting to rest the notion that FDR was compelled or forced to “hide” his disability for political gain.

Those who perpetuate the myth that FDR hid his disability from the public often cite as their evidence the very few known images of the President in his wheelchair. In doing so, they attach stigma to the wheelchair, perpetuating it as a symbol of limitation and weakness. But FDR changed that image. And in the case of American-Saudi relations, FDR’s use of the wheelchair proved to be politically advantageous and helped forge diplomatic ties between two nations.

Seth Frost, Museum Technician, Roosevelt & Vanderbilt National Historic Sites

This article was revised on July 11, 2024.

Image courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Endnotes

2 Minister to Saudi Arabia William A. Eddy to Secretary of State Edward Stettinius Jr., March 3, 1945; State Department, Office of the Historian Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, The Near East and Africa, Volume VIII - Office of the Historian

3 Eddy, F.D.R. Meet Ibn Saud, page 27 FDR MEETS IBN SAUD : WILLIAM A. EDDY : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

4 Eddy, "F.D.R. Meets Ibn Saud," page 13 FDR MEETS IBN SAUD : WILLIAM A. EDDY : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

5 President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Final Address to a Joint Session; United States House of Representatives; President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Final Address to a Joint Session | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

6 "FDR Hope For A Peace To Permit Disarmament," The Wilmington Morning Star, Wilmington, NC, page 2, March 1, 1945, The Wilmington morning star. [volume] (Wilmington, N.C.) 1909-1990, March 01, 1945, FINAL EDITION, Page 2, Image 2 « Chronicling America « Library of Congress (loc.gov).

7 Department of State, Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, The Near East and Africa, Volume VIII - Office of the Historian.

8 President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Final Address to a Joint Session; United States House of Representatives; President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Final Address to a Joint Session | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives

9 Jack Stinnett, “Stinnett Hears FDR Is Out in ’48; Wil Not Be Candidate,” The Daily Alaska Empire, March 27, 1945, pages 1 and 6, The Daily Alaska empire. [volume] (Juneau, Alaska) 1926-1964, March 27, 1945, Page SIX, Image 6 « Chronicling America « Library of Congress (loc.gov)

10 Stinnett.

11 “Roosevelt’s Swimming Pool,” Peninsular Enterprise, June 17, 1933, page 6, Peninsula enterprise. [volume] (Accomac, Va.) 1881-1965, June 17, 1933, Page SIX, Image 6 « Chronicling America « Library of Congress (loc.gov).

12 Stinnett.