Part of a series of articles titled A Victory Turned From Disaster.

Previous: Defense in the Cemetery

Next: Sheridan Arrives

Article

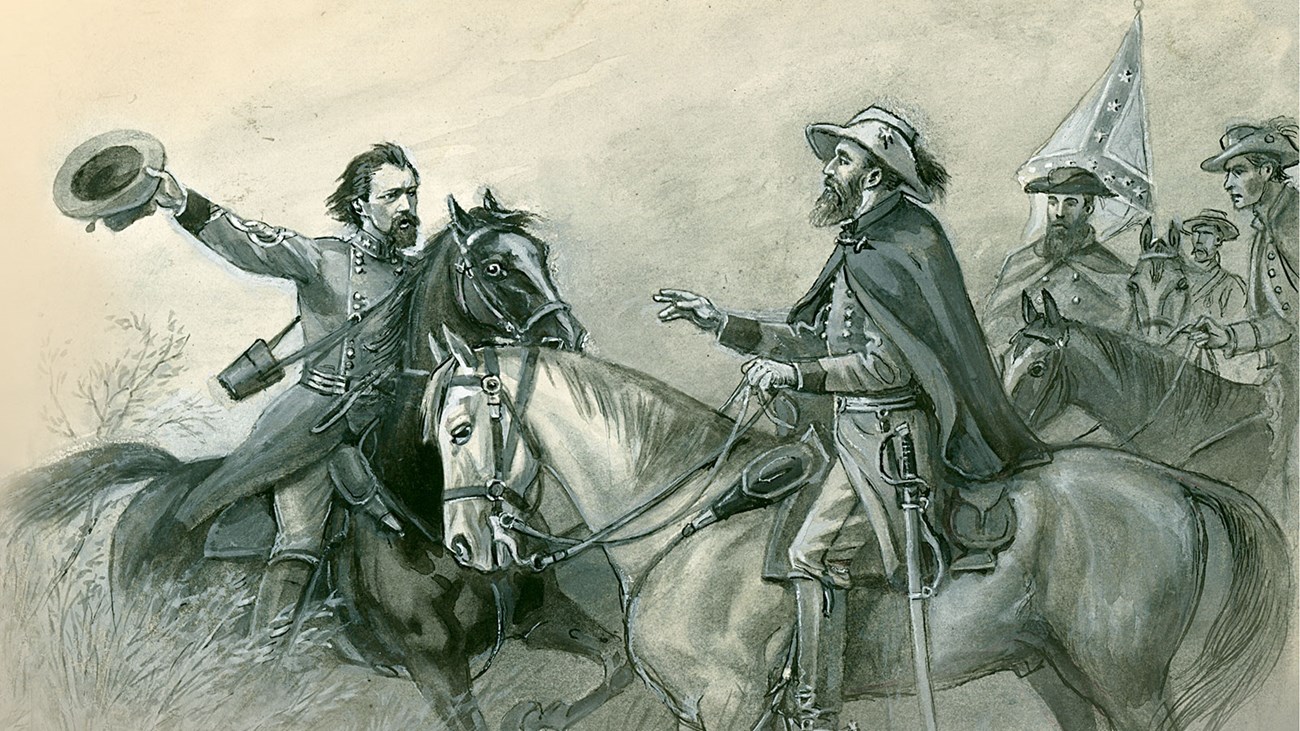

Sketch by James E. Taylor, an artist for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1864

“The concentration was stopped; the blow was not delivered… We halted, we hesitated, we dallied.”

—General John Gordon

10:30 a.m.—By late morning, about 14,000 Confederates had pushed approximately 32,000 Union soldiers out of their positions and sent them in full retreat through Middletown and almost one mile north of the village. General John Gordon and his commanding officer, General Jubal Early, met to assess the situation. Gordon urged continuing the pursuit. Early believed that the battle had been won. Some of his troops, he argued, had been on the move for over 12 hours and needed rest and food, and he worried about facing the formidable Union cavalry. Early decided to halt near Miller's Mill.

It was a decision that would haunt both men—and military historians—for years to come.

Gen. Gordon had led most of the Confederate infantry on the overnight march that drove the US 8th and 19th corps from their lines. According to Gordon, he then organized an infantry and artillery assault on the remains of the US 6th Corps positioned on Cemetery Hill. At this point, Gordon’s commander Gen. Jubal Early arrived on the field.

Reports from Gordon immediately after Cedar Creek have not survived. In his memoir published in 1904, he calls this time the “Fatal Halt:”

“My heart went into my boots… that the fatal halting, the hesitation, the spasmodic firing, and the isolated movements in the face of the sullen, slow, and orderly retreat of this superb Federal corps, lost us the great opportunity, and converted the brilliant victory of the morning into disastrous defeat in the evening.”

Two days after the battle, Early wrote a letter to Gen. Robert E. Lee in Richmond. Early reported the 6th Corps had

“sufficient time to form and move out of camp and it was found posted on a ridge on the west of the pike and parallel to it, and this corps offered considerable resistance. The artillery was brought up and opened on it, when it fell back to the north of Middletown and made a stand on a commanding ridge running across the pike… so many of our men had stopped in the camp to plunder (in which I am sorry to say that officers participated), the country was so open and the enemy s cavalry so strong, that I did not deem it prudent to press farther. I determined therefore, to content myself with trying to hold the advantages I had gained until all my troops had come up and the captured property was secured.”

Early believed that he faced the entire 6th Corps at the cemetery, as many as 8,500 well-disciplined troops, instead of only 2,500 men in one remaining division.

Early was also worried about the Federal Cavalry which formed on open ground north of Middletown. The cavalry in this position numbered between 5,000 to 6,000 troopers. The US Cavalry troopers, armed with breech-loading carbines, had an advantage in firepower. Twice in the past month they beat Early’s army at the battles of Third Winchester and Tom’s Brook.

Early blamed his troops and officers for a lack of discipline and their plundering in the Federal camps. In a memoir published in 1867, Early explained the condition of his Army. Neither Kershaw’s nor Gordon’s divisions were ready to attack. Both were scattered and needed time to reform. Later in the afternoon, after advancing outside of Middletown, Early said,

“It was now apparent that it would not do to press my troops further. They had been up all night and were much jaded. In passing over rough ground to attack the enemy in the early morning, their own ranks had been much disordered, and the men scattered, and it had required time to reform them. Their ranks, moreover, were much thinned by the absence of the men engaged in plundering the enemy's camps.”

To Early the morning attack was finished because of the entire 6th Corps at the cemetery, the powerful US Cavalry, and the disorganization of his men.

The term “Fatal Halt” circulated within post-war correspondence before Gordon published “Reminiscences.” Cpt. Augustus Dickert, 3rd South Carolina, wrote in “History of Kershaw's Brigade” in 1899,

“A general forward movement was made, the enemy making only feeble attempts at a stand, until we came upon a stone fence, or rather a road hedged on either side by a stone fence, running parallel to our line of battle. Here we were halted to better form our columns. But the halt was fatal— fatal to our great victory, fatal to our army, and who can say not fatal to our cause. Such a planned battle, such complete success, such a total rout of the enemy was never before experienced— all to be lost either by a fatal blunder or the greed of the soldier for spoils. Only a small per cent comparatively was engaged in the plundering, but enough to weaken our ranks.”

Historian Theodore Mahr wrote in 1992 that the Fatal Halt was not a single moment in the battle. It was a succession of delays with various causes:

“The first “halt” had occurred approximately between 9:30 and 10:00 am at the cemetery and had been primarily to allow Pegram and Ramseur to reform their division as well as to shift units to the southeast of Middletown to count the perceived Union Cavalry threat. The second delay was at the Old Forge Road some time between 11:00 and 11:30 a.m. and was initially to allow Kershaw and Gordon to come up on the army’s left flank. This halt, continuing until approximately 12:30 p.m., was the first real stoppage in the advance and was apparently extended to permit enough time for units to recall those reported stragglers in the rear areas. It was at this point that the loss of Confederate momentum would begin to prove fatal.”

The controversy surrounding the Battle of Cedar Creek spanned nearly 50 years, from the time of the battle well into the early 1900s. Early had the support of Lee but others blamed him, like Virginia’s Confederate governor William “Extra Billy” Smith. Smith asked Lee to remove Early. Smith thought Early to be a poor commander throughout the fall campaign.

Lee left Early in command but recalled most of his army to join Lee near Petersburg, under the command of Gordon. Early stayed in the Valley with about 1,000 men. Gordon took command of the Second Corps in the Siege of Petersburg and the Appomattox Campaign. He led the final Confederate assault at Fort Stedman and led last attack on the morning of Appomattox. Gordon was the officer selected to formally surrender the Army of Northern Virginia, on April 12, 1865.

After the war, Early lived in Mexico, Cuba, and Canada before returning to Virginia as an “unreconstructed rebel.” After Lee’s death in 1870, Early became Lee’s passionate defender. Gordon was elected to the US Senate from Georgia and also as that state’s governor. He served as Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans from 1890 until his death in 1904.

Augustus Dickert, History of Kershaw's BrigadeJohn Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War

Jubal Early, Correspondence to Robert E. Lee, dated October 21,1861

Jubal Early, Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence

Theodore Mahr, The Battle of Cedar Creek

Part of a series of articles titled A Victory Turned From Disaster.

Previous: Defense in the Cemetery

Next: Sheridan Arrives

Last updated: November 3, 2023