Last updated: July 28, 2021

Article

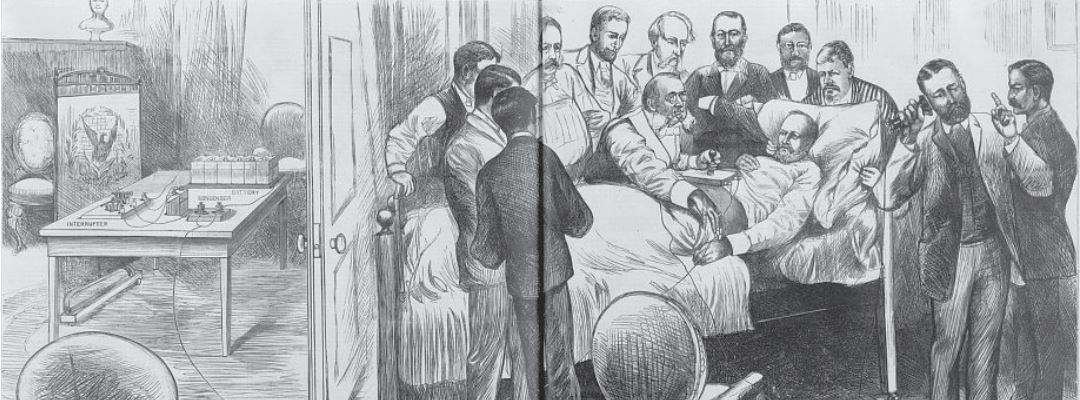

Famous Inventor Tried to Help Save President’s Life

Library of Congress

On July 2, 1881, President James A. Garfield was shot in the back by an assassin as he entered a train station in Washington, D.C. The president lingered, his condition teetering between improvement and decline, until he died on Sept. 19. During the course of the months-long ordeal, the famed inventor, Alexander Graham Bell, added a technological contribution to the desperate struggle to save the president.

At the time that the president was shot, Bell was working at a lab in Washington. As he followed the daily drama unfolding through the newspapers, Bell was appalled. The president’s physician, Dr. Willard Bliss, was obsessed with probing Garfield’s wound in order to extract the bullet from his body. Bell thought if he could develop a device that could find the bullet, Bliss could remove it more easily.

During his earlier work on the telephone, Bell stumbled across what he hoped would be the key to making a metal detecting device. Originally designed to balance the induction field of his telephone to clear up static interference, he noted that bringing metal objects toward the device caused a sound in the telephone receiver.

Working with his assistant William Tainter and other inventors and experts, Bell assembled his rudimentary metal detector in a few days. Refining the detector so that it would have an increased range beyond more than an inch or two, Bell tested it by firing rounds first into a wooden board and then into animal carcasses. Lastly, he performed tests on Civil War veterans who still had bullets in them.

On July 26, Bell made his first attempt to use his induction balance device to find the bullet. Bell immediately encountered problems. A new condenser, added to the instrument for the purpose of amplifying the electrical charge, was causing interference in the sound receiver. The first attempt at scanning Garfield’s body proved a failure as the static made it impossible to correctly hear if the device was detecting a metal signature.

Bell tinkered with the machine at his laboratory to rid it of the static interference. Once he was satisfied with the results, he conducted one last test on a Civil War veteran with apparent success.

Bell returned to the White House on Aug. 1. His search for the bullet was now hampered by Bliss, who was convinced that the bullet was located somewhere on the right side of Garfield’s torso, and refused to entertain any notions to the contrary.

As Bell moved the device across the president’s chest where Bliss had told him to scan, he found nothing. Bell suspected that the metal springs of the mattress of the bed Garfield was lying on may have interfered.

Bell’s device had worked, even if it was not clear at the time. Bell was not able to find the bullet with his metal detector because he was looking in the wrong place.

Everyone had feared as much, except for the one man whose opinion mattered most, Bliss. When the president’s body was autopsied, it was found that the bullet had lodged on the left side of Garfield’s chest, exactly opposite of where Bliss had contended it was.

At the time that the president was shot, Bell was working at a lab in Washington. As he followed the daily drama unfolding through the newspapers, Bell was appalled. The president’s physician, Dr. Willard Bliss, was obsessed with probing Garfield’s wound in order to extract the bullet from his body. Bell thought if he could develop a device that could find the bullet, Bliss could remove it more easily.

During his earlier work on the telephone, Bell stumbled across what he hoped would be the key to making a metal detecting device. Originally designed to balance the induction field of his telephone to clear up static interference, he noted that bringing metal objects toward the device caused a sound in the telephone receiver.

Working with his assistant William Tainter and other inventors and experts, Bell assembled his rudimentary metal detector in a few days. Refining the detector so that it would have an increased range beyond more than an inch or two, Bell tested it by firing rounds first into a wooden board and then into animal carcasses. Lastly, he performed tests on Civil War veterans who still had bullets in them.

On July 26, Bell made his first attempt to use his induction balance device to find the bullet. Bell immediately encountered problems. A new condenser, added to the instrument for the purpose of amplifying the electrical charge, was causing interference in the sound receiver. The first attempt at scanning Garfield’s body proved a failure as the static made it impossible to correctly hear if the device was detecting a metal signature.

Bell tinkered with the machine at his laboratory to rid it of the static interference. Once he was satisfied with the results, he conducted one last test on a Civil War veteran with apparent success.

Bell returned to the White House on Aug. 1. His search for the bullet was now hampered by Bliss, who was convinced that the bullet was located somewhere on the right side of Garfield’s torso, and refused to entertain any notions to the contrary.

As Bell moved the device across the president’s chest where Bliss had told him to scan, he found nothing. Bell suspected that the metal springs of the mattress of the bed Garfield was lying on may have interfered.

Bell’s device had worked, even if it was not clear at the time. Bell was not able to find the bullet with his metal detector because he was looking in the wrong place.

Everyone had feared as much, except for the one man whose opinion mattered most, Bliss. When the president’s body was autopsied, it was found that the bullet had lodged on the left side of Garfield’s chest, exactly opposite of where Bliss had contended it was.