Last updated: October 28, 2020

Article

Falling Stars: James A. Garfield and the Military Reputations of Generals Irvin McDowell, George McClellan, and Fitz John Porter

Library of Congress

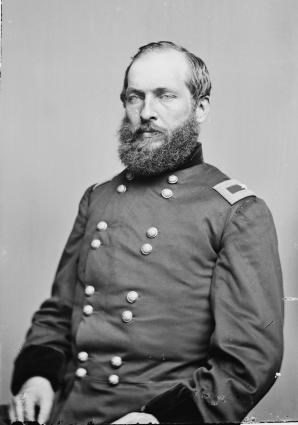

In September 1862, Brigadier General James A. Garfield received orders directing him to Washington, D.C. to confer with the War Department about his next assignment. By the time the government summoned him to the nation’s capital, Garfield had ably led Union troops in the Sandy Valley Campaign and at the tail end of the bloody battle of Shiloh. As of September 2, he was also a Republican candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives. (Voters of Ohio’s 19th Congressional District later overwhelmingly elected him to this office, but his Congress would not convene until December 1863, leaving him over a year left to serve in the Army.) Garfield went to Washington expecting to quickly receive his next assignment and return to the field. Instead, he languished there for months awaiting orders. During that long and difficult period, he was directly involved in one of the most celebrated military trials in American history: the court martial of Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter.

Library of Congress

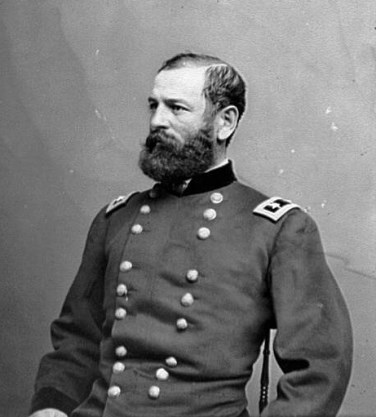

Porter, a native of Portsmouth, New Hampshire and a West Point graduate, was a close friend and ally of the controversial commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. Like McClellan, Porter was a loyal Democrat that believed slavery was sanctioned by the U.S. Constitution. Not until southern states seceded did Porter and McClellan agree that the North needed to take up arms. To them and many others, preservation of the Union, not abolition of slavery, was the North’s reason to fight.

After serving in McClellan’s unsuccessful 1862 Peninsula Campaign, Porter and his V Corps received orders to reinforce Maj. Gen. John Pope’s new Army of Virginia in the Northern Virginia Campaign. On August 29, 1862, Porter led his corps into the battle of Second Manassas (or Second Bull Run). During the battle Pope sent orders instructing Porter and his corps to attack the flank and rear of Confederate Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s wing of the southern Army of Northern Virginia. Porter had also been ordered to maintain contact with another Union corps and knew he could not do so if making the attack Pope wanted. Therefore, Porter elected not to attack. General Pope ordered Porter to make the same attack on August 30, and when Porter did so, everything he feared the day before came to pass, including his corps being routed by a much larger Confederate force. Furious, Pope accused Fitz John Porter of insubordination and relieved Porter of his command. Though McClellan soon returned Porter to his command and he led it through the subsequent Maryland Campaign and the battle of Antietam, Porter was arrested on November 25, 1862 for his actions at Second Manassas. By this time, President Abraham Lincoln had fired McClellan once and for all, so Porter’s closest ally was no longer in a position to help him.

Meanwhile, Gen. Garfield’s exile in Washington continued. He spent time with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton who, like Garfield, despised West Point-educated officers and considered them the bane of the army. His truest friend during this period, however, was Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, a fellow Ohioan who saw much of his younger self in Garfield. As Garfield biographer Allan Peskin states: “Chase and Garfield hit it off splendidly from the start. They had much in common: both admired Chase, despised copperheads [northern anti-war Democrats], and looked down on Lincoln…Garfield told Chase horror stories about the pro-Southern, proslavery West Point officers he had known, and Chase regaled Garfield with fresh tales of Lincoln’s incompetence.” General Garfield soon accepted Chase’s invitation to stay in the Secretary’s home during his time in Washington, which means James A. Garfield was then living under the roof of one of the Lincoln administration’s most radically anti-Democrat, anti-McClellan members. Secretary of War Stanton, another Ohioan and close friend of Garfield’s during this period, was also disgusted with McClellan’s leadership and politics. All were pleased that Lincoln had finally sacked “Little Mac,” but they still feared the influence of McClellanite generals in the Army—including Fitz John Porter.

National Archives

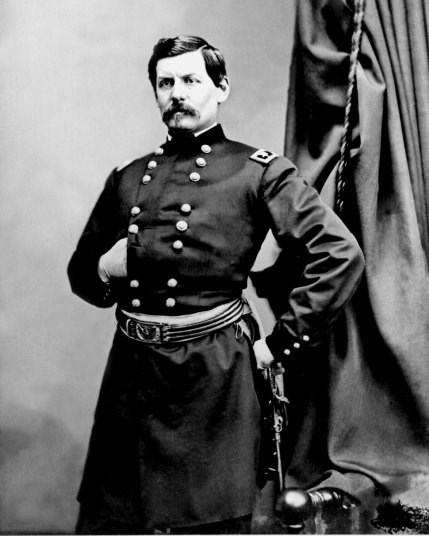

A second officer under scrutiny for his actions at Second Manassas was another Ohioan: Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell. His command had been one of three merged to create Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia that was soundly defeated at Second Manassas. McDowell came under criticism for his actions in that battle and requested a court of inquiry to clear his name. While he was being investigated, McDowell, a Republican and virulent anti-McClellanite, was also called as a prosecution witness in the Porter court martial. McDowell and McClellan despised one another, and since nearly everyone assumed the Porter trial was really aimed at McClellan, there was little doubt that McDowell would give damning testimony against Porter, both to harm McClellan’s reputation but also save his own. As he prepared for his own court of inquiry, McDowell requested a meeting with Gen. Garfield to informally state his case.

James A. Garfield left no doubt about his own anti-McClellan and anti-Porter feelings. Even before being assigned to the Porter trial, Garfield had maligned McClellan in letters to family and friends. He wrote his friend Harry Rhodes on September 22, 1862: “I am more disgusted at McClellan’s late operation of lying still a day and two nights after the great battle (Antietam), and letting the rebels cross the river and get safely away before he began the pursuit or renewed the attack. It confirms my opinion of his utter want of audacity and vigor. There is great bitterness here in regard to him.” Surely McDowell knew that Garfield was a vocal Republican and a U.S. Representative-elect. McDowell almost certainly sought the similarly-minded Garfield’s favor in an effort to gain an ally and save his own reputation and career.

Garfield wrote his wife, Lucretia, on October 3, 1862 and told her about his plans for the next day: “I shall spend the day with General McDowell, who will show me the history of the Virginia campaign. I believe he has been greatly wronged. The President and Cabinet know he is a true man but dare not come out before the people and vindicate him.” According to this passage, Garfield had already made up his mind of McDowell’s innocence before even meeting with him. Is it too great a leap to wonder if Garfield had also already determined Fitz John Porter’s guilt, if for no other reason than Porter’s loyalty to McClellan?

Garfield wrote his wife again on October 7 to report on his meeting with McDowell. He described McDowell as “a competent and reliable source” and stated: “I have never believed the absurd stories about McDowell’s being disloyal, or anything of that sort, but I was not prepared to find a man of such perfect, open, frank, manly sincerity. I believe he is the victim of jealousy, envy, and most marvellous [sic] bad luck–luck that came exceedingly near being splendid success, but failing of that turned the other way.”

National Archives

No doubt remains that by this time, before either the McDowell court of inquiry or the Porter court martial convened, James A. Garfield was squarely for Irvin McDowell. He must, therefore, have been just as squarely against Fitz John Porter. As if to remove any possible doubt, Garfield drafted a lengthy manuscript detailing the activities of McDowell, McClellan, and others during the Virginia campaign that resulted in the Union defeat at Second Manassas. The document, published as an Appendix to The Wild Life of the Army: Civil War Letters of James A. Garfield, edited by Frederick D. Williams, is almost comically pro-McDowell and anti-McClellan.

In it, Garfield writes that McClellan’s “loyalty has not been above suspicion…General McClellan made overtures to (Jefferson) Davis for a command before he was appointed to a position in the Union army…I consider him one of the weakest and most timid generals that ever led an army…I have no hope for the success of our arms in the East till McClellan is removed entirely from active command.” Irvin McDowell, however, “is frank, open, manly, severe and sincere. He is truly patriotic, but is not a politician…That he is a true brave man I have no doubt. I like General Irvin McDowell.” (Emphasis in original.) After finishing this manuscript, Garfield sent it to his wife with the instructions, “I would like to have you…read this…But it must not get into any hands that will make it public.”

Soon after writing this manuscript, Garfield was briefly assigned to the Court of Inquiry hearing General McDowell’s case. Had anyone known of his obvious bias toward McDowell, Garfield might never have received this assignment. However, he did not long remain on this case and was instead soon transferred to the much higher-profile court martial of Fitz John Porter. As Garfield was just as anti-McClellan (and therefore anti-Porter) as he was pro-McDowell, his placement on this court might have been questioned if his developing friendship with McDowell had been public knowledge. Of course, both Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, two of Garfield’s closest friends in Washington, wanted to see Porter convicted as a slap at McClellan. Both also surely knew of Garfield’s animosity toward McClellan, so it is entirely possible that one or both of them pulled strings to place Garfield on the court martial to increase the likelihood of conviction. General Porter, unaware of all of these machinations, was asked if he objected to any members of the court martial before the proceedings began. He answered that he did not. One wonders how strongly he might have objected to Garfield had he known all the details.

Garfield family/NPS

According to historian Allan Peskin, Garfield “had no great personal animus against Porter…Everyone knew that the trial was aimed at McClellan…The unhappy Porter was to be the sacrificial goat for the sins of his chief (McClellan).” Peskin further explains that many Republican military officers believed that officers who were Democrats were purposely dragging out the war in order to wear the country out and lead both sides to sue for peace, for which many Democrats had been advocating all along. A rumor had also surfaced that during a critical moment of the battle of Second Manassas, Fitz John Porter had advised McClellan to withhold reinforcements since “we have (General John) Pope where we can ruin him.” Porter’s rather arrogant attitude did not help him: he called Secretary Stanton an “ass,” referred to abolitionists as “our enemies in the rear,” and labeled Gen. Pope as a fool. The court martial was also comprised entirely of general officers of volunteers like Garfield. No West Pointers were permitted on the jury for fear they might have sympathy for their fellow alum Porter. As Peskin writes, “It was not a friendly court, and Garfield could well have been considered a hanging judge.”

The Porter court martial convened in December 1862. James A. Garfield wrote to his friend Harry Rhodes on December 14, telling him that Irvin McDowell had just testified before the court martial for two days with “direct and crushing” testimony. Garfield also told Rhodes: “On the whole I have a higher opinion of McDowell’s talents than of any other man’s in the army, and if he is again assigned a command I would prefer to go under him rather than any other. His history will yet be vindicated.” The case was complicated, as Peskin states: “The testimony was so tangled, the charges and countercharges so complex that years of patient investigation have not yet unraveled all of its intricacies. To the members of the court, however, there was no doubt whatsoever of Porter’s guilt. The only question in their minds was the proper sentence.”

Despite some initial extreme suggestions that Porter be executed, James A. Garfield and the court eventually decreed that Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter be immediately dismissed from the United States Army and forever barred from holding any federal office. Porter fought for his own vindication for the rest of his life, and two decades later his conviction was overturned. Of course, the damage to his personal and military reputation was long since done. Porter never forgave Garfield for his part in the sham court martial and was convinced that Garfield’s role in Porter’s disgrace was purely political. For his part, James A. Garfield remained convinced that the court had done the right thing in its judgment against Porter, saying at one point years later, “No public act with which I have ever been connected was ever more clear to me than the righteousness of the finding of that court.” Another member of the court, Gen. Benjamin Prentiss, agreed with Garfield’s assessment, stating “I am constrained to believe that under the circumstances our verdict was extremely light.”

Major General Irvin McDowell was (predictably) exonerated by his Court of Inquiry. Though he hoped to return to battlefield command against the Confederacy, he was instead basically exiled in the West, eventually becoming commander of the Department of the Pacific. He remained lifelong friends with James A. Garfield and even visited Garfield at his Mentor, Ohio home on November 21, 1880, almost three weeks after Garfield was elected President of the United States. Ten years prior to that visit, on August 3, 1870, James and Lucretia Garfield had welcomed their fifth child into the world. The infant boy was named Irvin McDowell Garfield.

James A. Garfield, of course, later served the Union army with distinction as Chief of Staff to the Army of the Cumberland and then as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 17 years prior to his election to the presidency.

George B. McClellan, fired for the second and final time by President Abraham Lincoln after the battle of Antietam, tried to avenge his reputation by running against Lincoln as the Democratic party’s presidential nominee in 1864. He lost to Lincoln by nearly half a million popular votes and 191 electoral votes. He served as Governor of New Jersey from 1878-1881. Today, McClellan is recognized by historians as a master organizer of Union troops during the Civil War but is criticized (as he was at the time by Lincoln and others) for an apparent lack of zeal for actual fighting.

The question of whether or not Garfield should have been permitted to serve as a juror on the Porter court martial remains. Clearly he was biased against Fitz John Porter by his earlier statements against McClellan and then by his burgeoning friendship with Irvin McDowell. Realistically, Garfield should probably have been forthright about his personal friendship with McDowell and, knowing that McDowell would be called to testify against Porter, recused himself from the Porter court martial. Of course, it is also quite possible that Garfield’s friends in high places—namely, Secretaries Stanton and Chase—had him placed on the court specifically because of his biases against McClellan and Porter. If that is true, Garfield may have knowingly allowed himself to be used for Stanton’s and Chase’s political purposes.

Why did he fail to recuse himself? One can only speculate, but Porter’s assertion that Garfield’s motivation was political is likely at least partially correct. Garfield was a Brigadier General in the Union army, but, as his election to the House of Representatives should have made clear to everyone, he was also a partisan Republican that sought to discredit Democrats like McClellan and Porter. He opposed them politically, of course, but also sincerely felt their ideas and policies were bad for the country. He also genuinely liked and respected Irvin McDowell and probably viewed his own presence on the Porter court martial as a way to provide some cover and protection for his friend. While we might accuse Garfield of a lack of impartiality here, we can also perhaps at least admire his loyalty to his friend.

James A. Garfield had his own reasons for failing to disclose his inability to be impartial in the case against Fitz John Porter. Over 150 years later, we can look at the evidence and say that, even if we might agree with his reasoning, in this particular instance, Garfield was wrong. The fact that he sometimes made mistakes and questionable decisions, though, makes him more human and therefore more accessible to us. His humanity is what makes him a fascinating figure to study. In this great but imperfect man, we can all see at least a little bit of ourselves.

Written by Todd Arrington, Site Manager, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, January 2014 for the Garfield Observer.