Last updated: November 3, 2020

Article

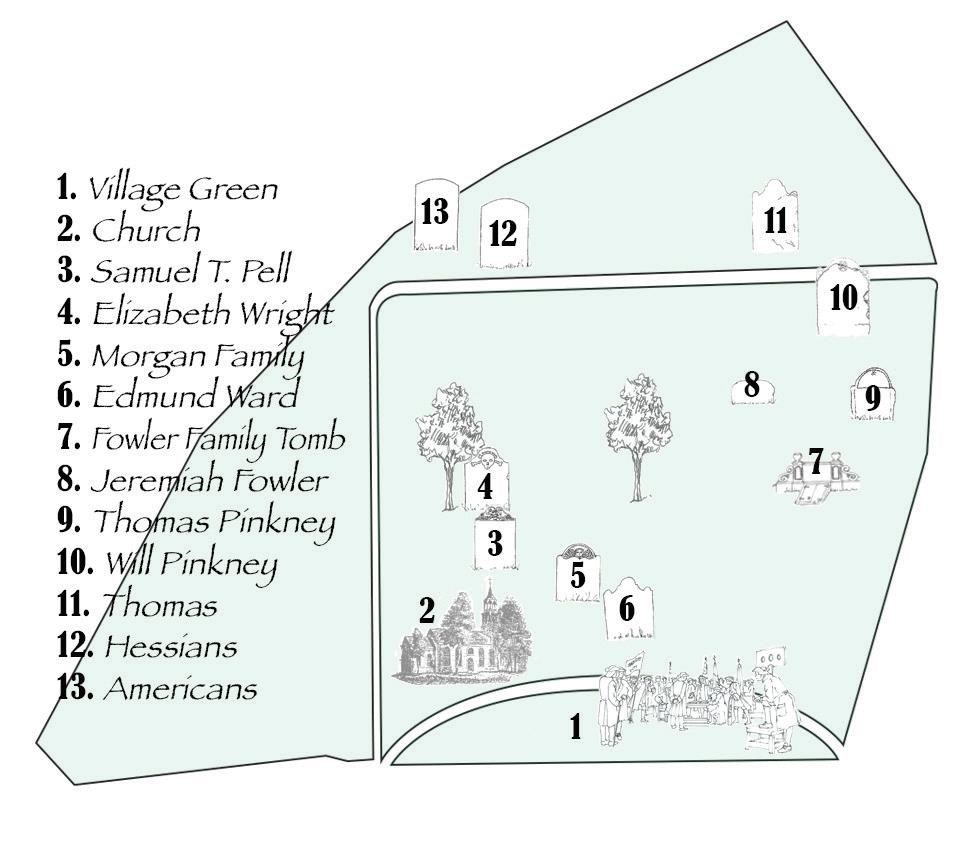

Exploring early American History at St. Paul's: A Self Guided Tour

Drawing by Rose James

A 13 Point Self-Guided Tour of the village green and historic cemetery

This is a self-guided tour of the historic cemetery and village green at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site, in Mt. Vernon, New York. It takes approximately 45 minutes. The tour explores the early history of Westchester County and our nation, with an emphasis on the colonial period and the era of the American Revolution. The points are marked by small American flags. The map included here will assist in locating the stops on the tour. It begins at the flagpole on the village green. For more information on the topics covered in this tour, please visit our website, www.nps.gov/sapa.

- This is the remnant of the village green or town common of Eastchester. Located at the crossroads of Westchester County, It was the site of an important and controversial special election for an open countywide seat in the General Assembly of the colony of New York, on October 29, 1733. It is one of the earliest documented elections in our nation’s history, covered through a lengthy account in the inaugural issue of The New York Weekly Journal. In rare detail, the account reveals the rituals, procedures and animating issues of early American political life in a scene that was as much a social gathering as an electoral exercise. Lewis Morris, former Chief Justice of the colony, and leader of a party opposed to New York’s high-handed Royal Governor Williams Cosby, defeated William Forster, the county clerk and the governor’s preferred candidate. The election was notable because of the sheriff’s disenfranchisement of Quaker supporters of Morris through the legally questionable imposition of a required Biblical oath, which violated Quaker religious beliefs. A year later, in direct response, the colonial assembly passed a law giving Quakers the right to affirm rather than swear on public occasions, an important milestone in the development of religious freedom in the colonies.

- The original settlers of the Town of Eastchester were Puritans, dissenters, opposed to the Church of England. But the British established the Church of England in the parish in 1702, part of a strategy to strengthen colonial administration, leading to a religious controversy that lasted for several decades. Buried beneath the church is the Rev. Thomas Standard, one of the rectors of the Church of England parish, who died in 1760. He was originally buried beneath the town’s small wooden meetinghouse, which stood about 60 yards west of this edifice, and his coffin was re-interred here in the early 1800s. Rev. Standard’s name is inscribed in the small bronze bell that he purchased for the church, and still hangs in the belfry. It was cast in 1758 at the same London foundry as the Liberty bell.

- Samuel Treadwell Pell served as an officer in the Continental Army for the entire Revolutionary War. He survived the infamous Valley Forge winter encampment of 1778, and was part of the army that defeated the British at Yorktown in October 1781, effectively ending the war. Pell survived the war, never married, and died from injuries sustained in a horse accident in a snowstorm in late December 1786. His family arranged for this finely chiseled sandstone monument. Carved by New York craftsman Thomas Brown, it features a Trophy of Arms at the top, and an allusion to Mars (the Roman God of War) in the epitaph.

- The sandstone grave marker for Elizabeth Wright displays the skull and crossbones, one of the haunting images of colonial burial yards. A symbol of death, it functioned as a community reminder about the fragility of life, when contagious diseases. the primitive state of medicine and local conflicts could mean that death was always lurking around the corner. On the stone, the phrase at the top “Remember to die” and the epitaph, “Mortals beware, improve ye day while vital spirits animate ye clay” would remind people walking by not to wait too long to improve their personal, religious and community behavior. Elizabeth, the wife of a doctor, died in 1766 at 34, shortly after her two sons, buried in a common grave at right, had died at ages 10 and eight months.

- Re-marriage upon death of a spouse was common in early America, when the myriad of domestic responsibilities in a pre-industrial world required the combined efforts of husband and wife. Caleb Morgan’s sandstone marker is flanked by memorials for his two wives. At left is his first wife Elizabeth’s stone, featuring a carefully carved soul effigy, or angel, reflecting a more positive view of the chances of salvation than the death head on Elizabeth Wright’s stone. Caleb’s second wife Isabella, who had lost her first husband, is buried to his right. In an indication of the limited legal status of women at the time, Isabella surrendered claims to her property to Caleb when they married.

- Edmund Ward’s life during the Revolutionary War illuminates the experience of many New York Loyalists. A wealthy landowner, he sided with the Crown and was imprisoned by Patriot militia in White Plains in 177 Later banished and confined in Massachusetts, he escaped and fled to New York City, headquarters of the British army, where he spent most of the war. His wife Phoebe and their children remained on the farm in Eastchester, enduring the difficulties of the notorious “neutral ground,” a no man’s land, caught between the armies, with no civilian authority. In 1783 his estate was confiscated and auctioned off by the State of New York, one of many Westchester supporters of the British who lost their land. The Ward family followed many Loyalists into exile in Nova Scotia, an English possession. They were part of a pattern of former Loyalists who quietly returned to America in the 1790s, though they never regained their large estate, settling on a small farm in the area.

- The Fowler family tomb reveals divisions over the American Revolution. The maker at the left of the entrance memorializes Theodosius Fowler, an officer in the Continental Army, who served almost continuously from 1776 – 1783. His tenure included combat in almost all of the important battles in the Northern theatre of the Revolutionary War, and command of an elite Light Infantry company. Associations forged with fellow officers, including Alexander Hamilton, helped facilitate a successful career as a merchant after the war. He lived until 1842, at age 89, followed by burial in the family plot. Also interred here is his father Jonathan, who was a judge and militia leader, the town’s leading and wealthiest resident on the eve of the Revolution. Perhaps because of those positions, he opposed the Revolution, sided with the Crown, and went into wartime exile in Canada, passing away in the 1780s. There is no indication that father and son reconciled their searing political differences.

- The modest granite gravestone of Jeremiah Fowler is among the oldest legible markers at St. Paul’s. Town population was perhaps 350 when he passed away in 1724, including children and many people of limited literacy. For those who might visit the cemetery, when there were a small number of extended families and almost everybody knew each other, initials were sufficient to identify the deceased. Hence, JF (Jeremiah Fowler) was enough. He died (D) on November The Fourteen Day 1724, with an emphasis on the date of death because that was the only record at a time of no death certificates. While the stone appears simple and non-descript, Fowler was actually one of the town’s wealthier citizens. Many people of less wealth were buried with no headstone. Since people were generally buried near a church, the placement of his grave also recalls the location of the town’s earlier wooden church, which was situated toward the street from where you are standing. It was destroyed for fuel during the Revolutionary War.

- Thomas Pinkney, buried here, was the son of Philip Pinkney, one of the founders of the town, who drew up the 26-point Eastchester covenant in 1665, one of the oldest surviving community foundation documents. These covenants, agreed upon by all town residents, developed religious and civil laws for Puritan communities. It required residents to maintain a life of religious love, civic virtue, public honesty and “a good fenc about all ye arable land,” among other things. Thomas, who died in 1732, would have worshipped in the earlier wooden meetinghouse, located about 30 yards north of his grave.

- Will Pinkney, who died in 1755, was a captain of the Eastchester militia. The town militia was a necessary force in isolated colonial communities, far from British support. It drilled monthly on the green, and all able-bodied men age 16 to 60 were expected to participate. Additionally, militia fought alongside the English in some of the colonial wars. But the militia was also a social and political institution. Commission as an officer in the militia, in Eastchester and other colonial towns, was a traditional form of service and development of leadership among young men from notable families. Monthly militia drills were festive gatherings of people on the village green in front of St. Paul’s Church. Pinkney’s sandstone marker, though somewhat damaged, reveals two of the earlier symbols of iconography -- the heart (a symbol of religious love) and the star, looks like a modern asterisk, a symbol of heaven.

- New York had a greater population of enslaved people than any other Northern colony, reflecting an acceptance of the widespread racial prejudice of the day. New York’s merchants were heavily involved in the African slave trade and the colony’s restrictive land policies discouraged settlement by free laborers. The enslaved were used as domestic servants, farm hands and as apprentices to master craftsmen. Until the early 19th century, enslaved Africans represented about 15-percent of Eastchester’s population, including Thomas. His sandstone marker includes the only known reference on a Westchester County cemetery monument to “servant,” a euphemism for slave.

- During the Revolutionary War, the British hired auxiliary troops from the German state of Hesse-Cassel to assist with the fight against the Americans. Hesse was a small, landlocked principality whose army, modeled on the Prussian army, was a valuable source of revenue, and would be available to a friendly power, like England. The Hessians accounted for some of the 4,000 man British force that engaged the Americans at the Battle of Pell’s Point, about a mile from here, on October 18, 1776. A small American brigade delayed the march of the larger British force and helped General Washington’s main army safely withdraw from northern Manhattan to White Plains. After the battle, the Hessians occupied St. Paul’s Church for use as a hospital, and some of their young privates who died of illness were buried here in a pit that had been used to compose mortar for construction of the church.