Last updated: March 6, 2023

Article

The Enslaved Community of Snee Farm

Now called Charleston, the city’s success as a leading port for the colony came from the naval stores industry, the lucrative trade with Native Americans in deerskins and fur, and the development of plantation-based agriculture. This production system relied on the labor of enslaved people to raise livestock and grow tobacco, a major boost to South Carolina’s thriving economy.

By the early eighteenth century, rice became the dominant crop in the “Lowcountry.” Many enslaved people grew rice in Africa, and planters depended on their knowledge and skill to be profitable. Charleston’s position as a financial and mercantile hub was a result of these enslaved men, women, and children – white planters and merchants merely reaped the rewards of their labor.

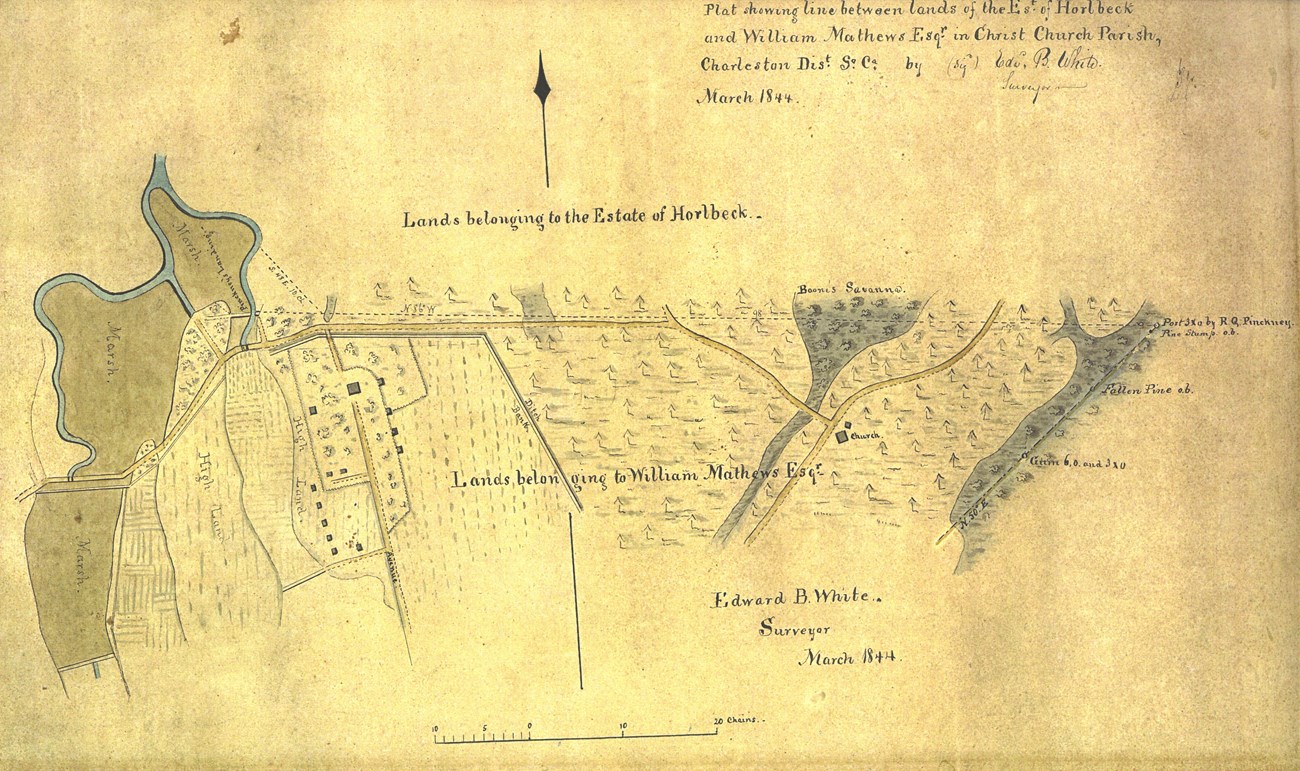

Colonel Pinckney purchased Snee Farm, his first plantation, in 1754. Pinckney constructed a new residence on the property shortly after. “Snee” is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as meaning bountiful or plenteous. It was an apt name. South Carolina’s wealth and political power was concentrated in a few of the state’s leading families, the Pinckneys being one of them.

At 21 years old, Colonel Pinckney’s son, Charles, became a state representative in 1778. Colonel Pinckney passed away in 1778, leaving both Snee Farm and the family home in Charleston to Charles.

The 1790 census lists him owning 111 enslaved people, around 40 of which lived at Snee Farm. By 1810, Gov. Pinckney enslaved 58 people at Snee Farm alone.

What the Artifacts Reveal

In the East Yard of Snee Farm, archeologists discovered an abundance of colonoware, a type of unrefined, handmade earthenware ceramic. Colonoware was the most widely utilized class of historic ceramic ware for enslaved people due to its ease of manufacture and inexpensive cost. For plantations like Snee Farm with large, enslaved populations, colonoware is frequently the greatest quantity of ceramics recovered archeologically.

Enslaved families once lived in Structures 13 and 16. The enslaved built these homes before Pinckney ownership in the eighteenth century, and later generations occupied both structures well into the nineteenth century, long after the Pinckney family sold the property. Archeologists found whiteware artifacts near these sites, including a significant amount of porcelain, wine bottle fragments, and elaborate tablewares.

Closer to the Pinckney’s main house, Structure 16 is a smaller residence compared to Structure 13. Excavations yielded machine-cut nails dating to the late eighteenth century. Archeologists recovered several eighteenth-century beads and a ‘tombac’, or brass alloy, button that was likely manufactured in the eighteenth century.

The residence also yielded a large variety of personal recreational items such as tobacco pipe fragments, marbles, brass thimbles, a fishing weight, a pencil, a fragment of a porcelain toy doll, and a piece of writing chalk.

Uncovering the Village

Archeologists conclude that the enslaved occupied the residences of Snee Farm for more than seventy years. The archeological evidence indicates that the structures were not arranged in formally planned rows, but rather grouped together in a cluster of loosely spaced units. Field workers lived in a village composed of single or duplex structures characterized by a variety of housing types, ranging from post-in-ground, wattle and daub structures reminiscent of African styles of construction, to log cabins, framed lumber cabins, and brick or tabby structures.

Although little is known about the enslaved population, probate inventories tell us there were skilled laborers such as coopers, drivers, seamstresses, and cooks. These abilities allowed the enslaved some freedom to work off the plantation, providing opportunities for personal prosperity and financial independence. Yet, the average enslaved person worked nine-, ten-, or even eleven-hour days. The idea of “free time” might have merely been a carrot dangling on a stick in front of the enslaved person, a way for the enslavers to encourage faster work.

Source

Keel, Bennie C., and Amy C. Koval2014 The Archeology of Charles Pinckney’s Snee Farm: A Summary of Fieldwork 1987-1999. Southeast Archeological Center, National Park Service. Tallahassee, Florida.