Last updated: April 14, 2024

Article

Emancipation in Washington, D.C.

Library of Congress

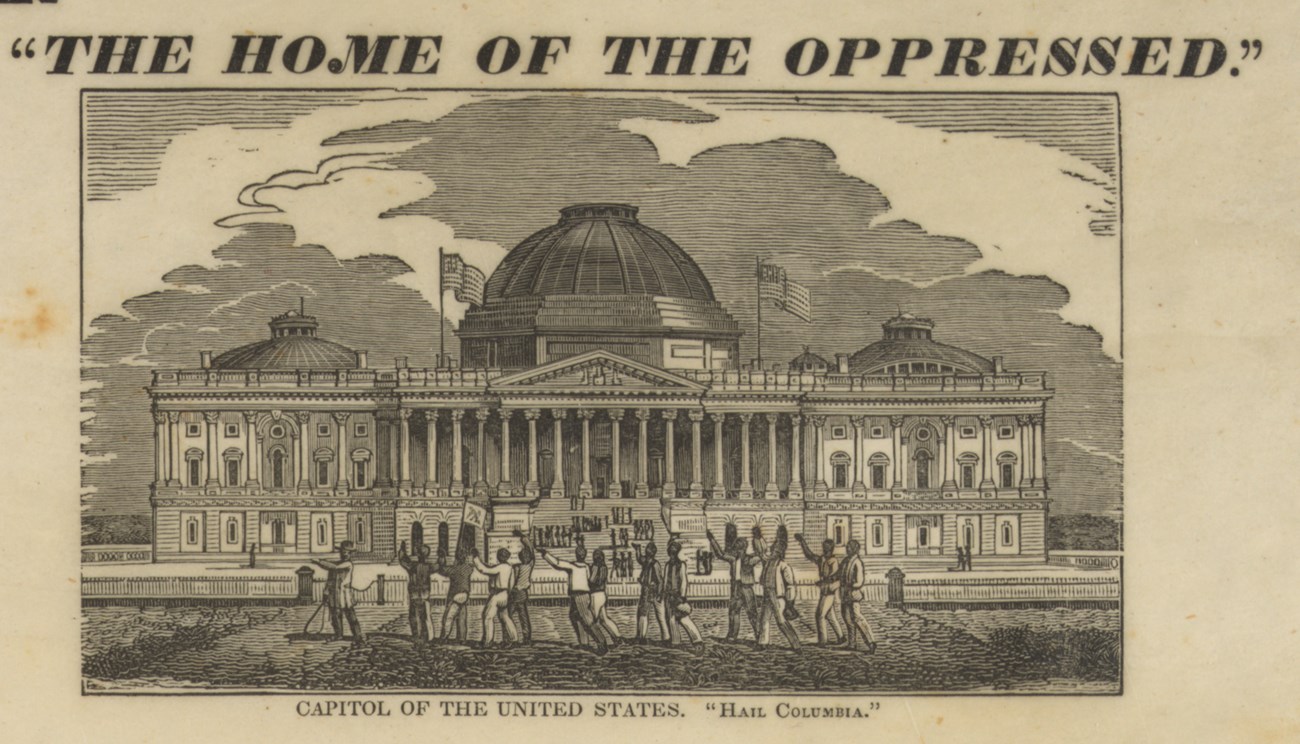

From its beginning, Washington, DC was set to be the capital city of the United States, the symbol of a nation founded on liberty and equality. In a gruesome irony, the city also became home to a thriving trade in enslaved people. It was not until 1862 that Congress passed a law ending slavery in the District of Columbia. That law, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, has become an integral part of the city’s heritage.

First Attempts for Freedom

Soon after the founding of Washington, DC, many observers noted the contradiction of slavery in the nation’s capital. Congressmen and citizen-activists worked to abolish slavery in DC, but they encountered strong proslavery opposition. Meanwhile, enslaved people in the nation's capital took actions of their own to resist bondage. On April 15, 1848, 77 enslaved men and women attempted a daring escape aboard a ship called the Pearl. The escape was unsuccessful, but the Pearl affair caused intense debates in Congress over slavery.

Library of Congress

Lincoln and D.C. Emancipation

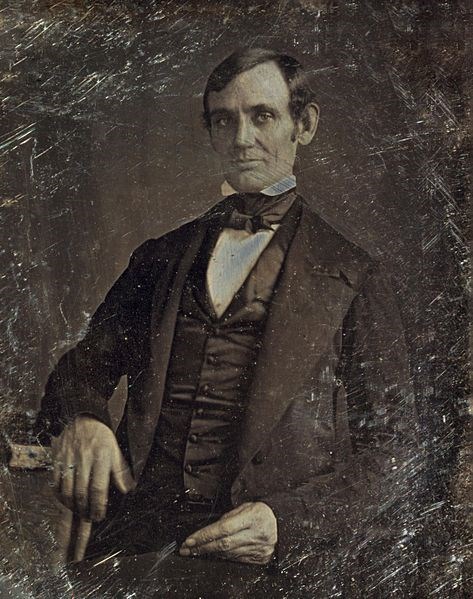

Thirty-eight-year-old Congressman Abraham Lincoln first entered national politics—and the nationwide debate over slavery—in 1847. He boarded with other young congressmen in a house near the capitol. There he became friends with many of the legislature’s most vocal abolitionists. Lincoln held conflicted views on emancipation at the time. He personally despised slavery, but he was skeptical that any national emancipation law could pass Congress.

Because Congress had complete control over laws in Washington, DC, Lincoln saw a chance for compromise. He proposed a law to emancipate enslaved people in the District of Columbia but also compensate enslavers for the loss of their "property." Joshua Giddings, one of Lincoln’s abolitionist housemates, supported the bill and helped Lincoln write it. However, Lincoln's DC emancipation plan failed to gather enough support to become law.

Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress

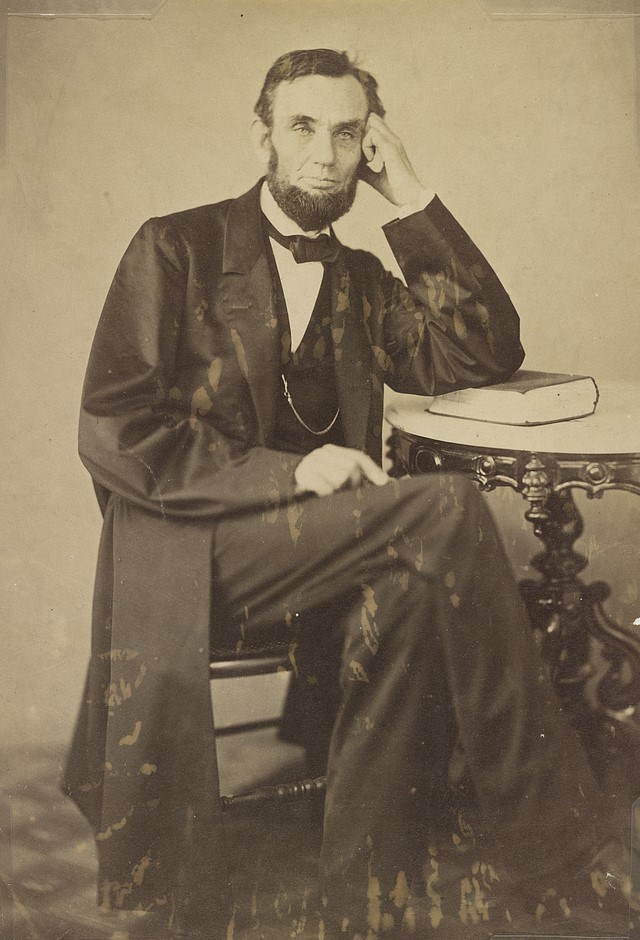

Fifteen years later, Lincoln returned to DC. This time, he was President of a nation divided by Civil War. In the spring of 1862, the Civil War was transforming Washington, DC. Thousands of enslaved people escaped from Confederate plantations to take refuge with the US Army. President Lincoln pushed border states like Kentucky and Maryland to abolish slavery. Abolitionists in DC decided it was time to act. "This is the best place to try the experiment of emancipation,” Senator John Sherman wrote. “Let us try it.”

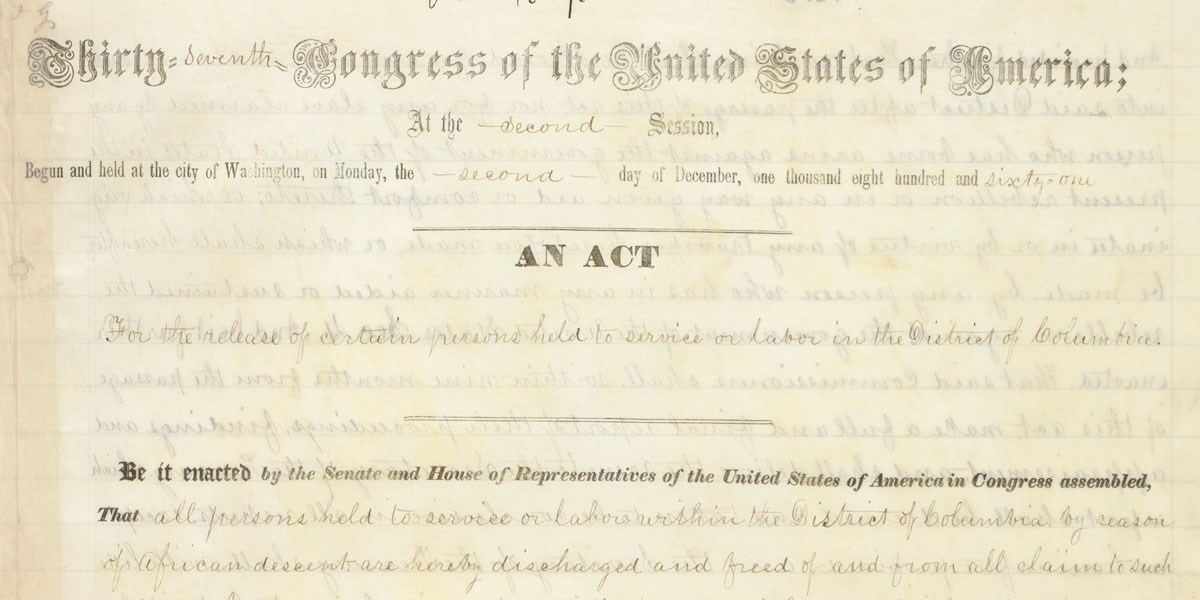

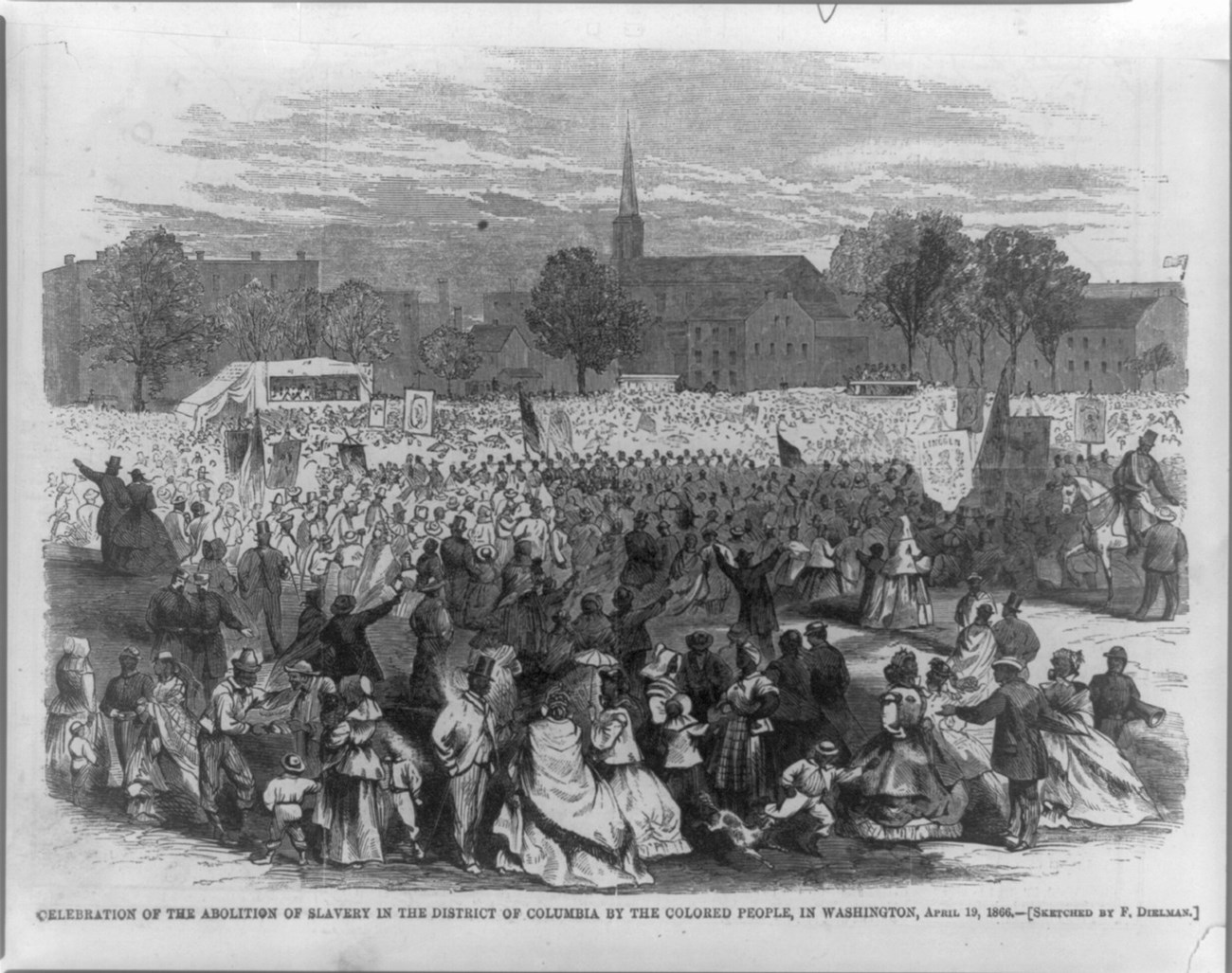

Sherman and other members of Congress drafted a law to end slavery in DC. The act resembled Lincoln's plan for emancipation in the border states. People enslaved in DC would be free immediately, but the federal government would compensate enslavers for the loss of their "property." Controversially, the act also included funds for freed people to resettle in Africa or South America. This idea found little support among the Black community. Congress passed the act in a landslide vote, and President Lincoln signed it on April 16, 1862. In a message to Congress, Lincoln wrote, “I have ever desired to see the national capital freed from the institution in some satisfactory way.” The DC emancipation act was the first emancipation law passed by the US government. The journey to national abolition had begun.

National Archives

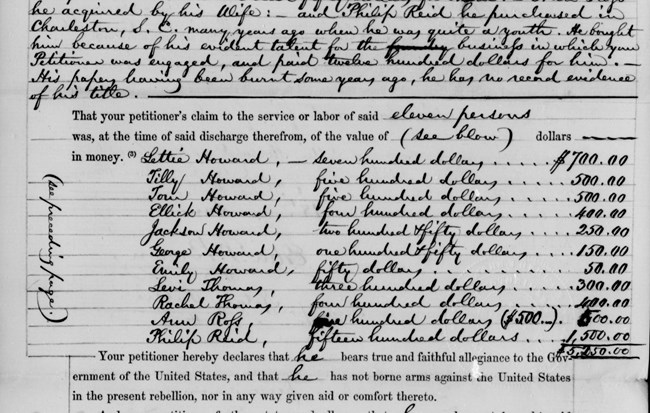

The DC emancipation act immediately declared 3,000 enslaved Washingtonians forever free. Enslavers also benefitted through payments of up to $300 per person from the federal government. To claim their payments, enslavers needed to file petitions before a three-person commission. These documents had to include proof of ownership, descriptions of the enslaved, and proof that the petitioner "had not borne arms against the United States in the present rebellion."

National Archives

Freedom

One of the enslaved people freed by the act was 42-year-old Philip Reid. Reid was enslaved by the famous sculptor Clark Mills. Mills relied on Reid's mechanical skills at his bronze foundry in northeast Washington, DC. When the DC emancipation act went into effect, Reid was hard at work on a monumental sculptural project. He was casting the 19 1/2-foot-tall Statue of Freedom, which would adorn the top of the US Capitol dome. Reid appeared on Clark Mill’s petition alongside 10 other men, women, children. Mills described him as “not prepossessing in appearance, but smart in mind, a good workman in a foundry.” After the war, Reid opened his own plaster shop in DC.

Architect of the Capitol

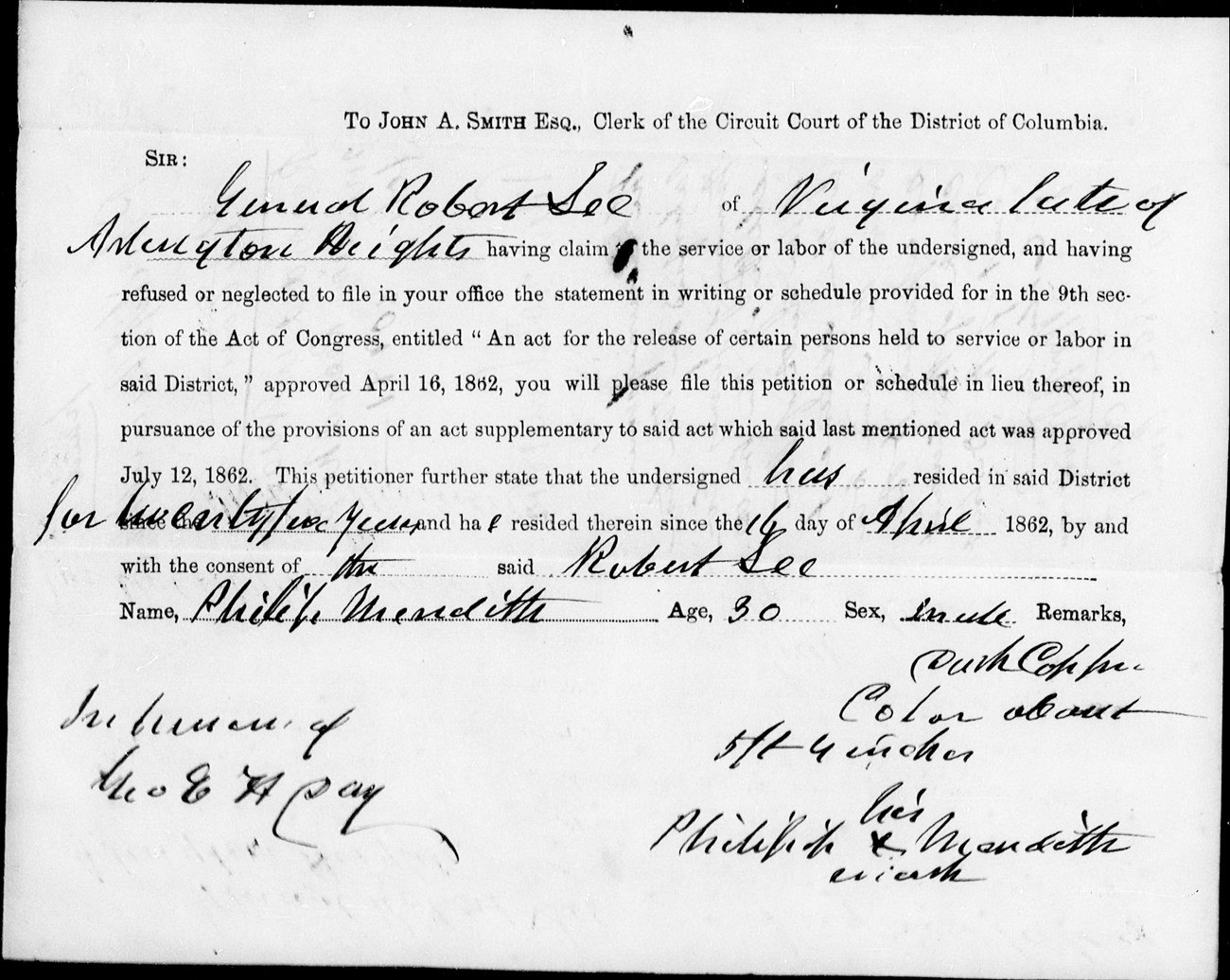

Some enslavers refused to acknowledge the law and attempted to keep enslaved people in bondage illegally. Congress passed a supplemental law in July 1862 that allowed these victims to file petitions on their own behalf. Though the formerly enslaved people found freedom by advocating for themselves, they did not receive the $300 payments.

The DC emancipation act also freed enslaved people whose owners had aided the Confederate rebellion. No one met that definition better than Philip Meredith, a 30-year-old waiter enslaved by Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Meredith spent 25 years working in DC and sending most of his wages back to Lee. He supported his wife Lydia and eight children with whatever money remained. When Lee resigned from the US Army and traveled south to join the rebels, Meredith remained in DC. For all practical purposes, he was a free man. Once the DC emancipation act passed, Meredith filed a petition to make his freedom official. The commissioners approved Meredith’s petition almost immediately. Unsurprisingly, they did not pay compensation to Robert E. Lee.

National Archives

Library of Congress