Part of a series of articles titled People of the California Trail.

Article

Eliza Donner Houghton, the California Trail

by Houghton" by Eliza P. Donner.

Image/Public Domain

Eliza Donner Houghton – California Trail

By Angela Reiniche[1]

On 14 April 1846, three-year-old Eliza Donner left Springfield, Illinois, and set out for California in a covered wagon with fifteen members of her extended family. The family name would soon go down in history for the tragedy that overtook them on the long trail to California.

Barely out of toddlerhood, Eliza may not have shared the optimism and anticipation felt by her father, George Donner, as they left their comfortable home for an uncertain future in the West. A well-respected, sixty-year-old man with a prosperous farm, “Uncle George”—as he was known to friends and neighbors—had no need to take his wife and five children on a perilous trek to start a new life in California. Perhaps he simply wanted a challenge. He would get one.[2]

Eliza’s parents, George and Tamsen (Tamzene) Donner, left behind in Illinois a 240-acre farm and orchard, evidence of their relative affluence and their ability to undertake the expensive overland journey to the Pacific Coast. George recruited and hired stronger, younger men to perform the most arduous tasks along the trails. The party, consisting of the Donners and some Springfield neighbors, “jumped off” onto the California Trail from Independence, Missouri, on 12 May 1846. It was a bit of a late start, but their nine wagons soon caught up and joined a train of thirty-five wagons captained by William Henry Russell.

From the time that Eliza and her family joined the Russell company, she witnessed through young eyes the best and worst of overland travel. Along the way, she witnessed the funeral of fellow traveler Sarah Keyes, she weathered the storms and the intense heat of the prairie crossing, and—though she may have walked some of the way—Eliza undoubtedly experienced the rough jostling of the slow-rolling wagons. Her mother wrote to a friend at home that Eliza shared breakfast with “the chiefs of a local tribe” and experienced a “countryside beautiful beyond description.” The little girl may have found the smell of burning “buffalo chips” unpleasant but likely forgot the odor as she “dined on buffalo steaks that were as tasty as if they had been cooked over hickory coals.”[3]

The series of unfortunate—and compounding—events that would lead to much of the party’s demise began in mid-July. Members of the larger wagon company had different ideas about where to go and how to get there. One faction, including the Donners, decided to try the Hastings Cutoff, a new route that would take them south of the Great Salt Lake and supposedly cut several hundred miles from the journey. That group elected Eliza’s father, George, as its captain and turned onto the Hastings track on July 19. Others would join them, ultimately bringing the Donner Party to ninety-one members. The “cutoff” took them much longer than expected.[4] Tensions within the company rose to a boiling point. The lateness of the season, plus the party’s dwindling provisions and the loss of draft animals, weighed heavy on Eliza and her traveling companions.[5]

An impeding storm, which struck on 30 October as they attempted to forge on through the snowy passes, would prove to be the party’s undoing. By then, the wagons had become strung out and separated. About three-quarters of the Donner Party sought refuge in cabins and shelters at the “lake camp,” while Eliza and her family huddled in a crudely constructed lean-to six miles away at Alder Creek. The miserable weather hampered relief efforts. Eliza’s uncle, Jacob, was the first at their camp to die; many others followed, weakened by starvation and exposure. Eliza’s father had suffered a hand injury while repairing a wagon, and his wound grew gangrenous. He spent the winter bedridden, lovingly tended by Tamsen.[6]

The first team of rescuers came east over the Sierra Nevada from the California settlements to help the stranded travelers, reaching the Lake Camp on 18 February 1847. Members of the “third relief” arrived on 13 March to take Eliza and her sisters to Johnson’s Ranch (north of present-day Sacramento). Eliza, being so tiny and weak, had to be carried every step of the way. She would never see her parents again.

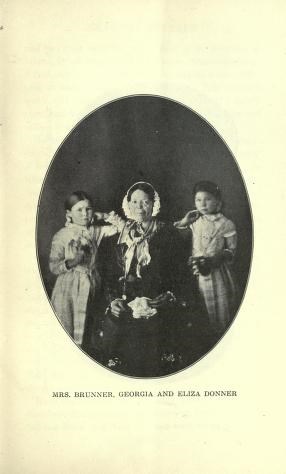

At Johnson’s, Eliza and her sisters reconnected with other survivors. The next day they arrived at Sutter’s Fort (Sacramento), where they reunited with their half-sisters Elitha and Leanna. The girls continued to wait for their parents to return, but in May a messenger delivered the awful news. Word of George and Tamsen’s deaths spread throughout the fort, and—despite the kindness people there displayed to Eliza—she found it overwhelming and “would rush off alone among the wild flowers to get away from the torturing sympathy.”[7] A kind Swiss couple took Eliza and her sister Georgia into their home for seven years; in 1854, though, the sisters moved to Sacramento to be with Elitha and her family. Eliza remained there for six years, and in 1861 she married a veteran of the Mexican American War named Sherman Houghton who went on to serve two terms in Congress.[8]

In 1911, when Eliza was in her sixties, she published her memoir, The Expedition of the Donner Party and its Tragic Fate. Interestingly, while some survivors of the Donner Party went out of their way to shun their maiden names (or anything else that would attach them to such a tragic and sensationalized event), Eliza did no such thing. The title and cover page of her book read ‘Eliza P. Donner Houghton.’[9] After a popular 1879 account downplayed accusations of cannibalism at the Alder Creek camp, popular sentiment about the Donner Party began to change; in fact, the Native Sons of the Golden West erected a monument to the expedition. At the monument’s dedication in 1918, Eliza occupied a prominent position just to the right of the speaker’s podium. During a reception the day before, however, she became overcome with emotion while trying to give a short speech.[10] Though she did not hide her connections to the events of 1846-47, they would stay with her forever. She passed away on 19 February 1922 – seventy-five years to the day after the arrival of the First Relief.

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails- National Park Service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children.

[2] Several books feature relatively recent historical scholarship on the Donner Party. See Michael Wallis, The Best Land Under Heaven: The Donner Party in the Age of Manifest Destiny (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a Division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2017); Kelly Dixon, Julie M. Schablitsky, and Shannon A Novak, An Archaeology of Desperation: Exploring the Donner Party's Alder Creek Camp (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011); Gabrielle Burton, Searching for Tamsen Donner (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Ethan Rarick, Desperate Passage: The Donner Party's Perilous Journey West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); Donald L. Hardesty and Michael J Brodhead, The Archaeology of the Donner Party (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1997); Frank Mullen, Marilyn Newton, (Photographer), and Will Bagley. The Donner Party Chronicles: A Day-By-Day Account of a Doomed Wagon Train, 1846-1847 (Reno, Nev.: Nevada Humanities Committee, 1997); and Kristin Johnson, Unfortunate Emigrants: Narratives of the Donner Party (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1996).

[3] Eliza describes her mother’s letters in her memoir of the Donner Party’s overland journey on the California Trail. Eliza Poor Donner Houghton, The Expedition of the Donner Party and Its Tragic Fate (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1911), 24-25. The details that Eliza related about her journey come primarily from memories and stories reconstructed with the help of conversations with Jean Baptiste Trudeau, an older survivor of the winter the Donner Party spent in the Sierra Nevada. Closer to the time of the event, in 1879, Eliza collaborated with the editor of the Truckee Republican, Charles Fayette McGlashan, to create a series of six articles describing for the public the party’s winter ordeal. Eliza had long desired to set the record straight about she and her family’s experiences, correcting the rumors surrounding the Donner’s participation in cannibalism, her mother’s death, and their rescue. She ended up publishing her own book later after coming into contact with Trudeau and learning new details of their journey, those that she could not remember because of her young age at the time.

[4] Ibid., 32-33.

[5] C. F. McGlashan, History of the Donner Party: Tragedy of the Sierra (Sacramento: H. S. Crocker Co., Printers, 1902), 34-43.

[6] Houghton, 59-122 (passim).

[7] Ibid., 119-38; quote from 138.

[8] McGlashan, 189-91.

[9] Ethan Rarick, Desperate Passage: The Donner Party’s Perilous Journey West (Oxford University Press, 2008), 230.

[10] Ibid., 244.

Last updated: March 9, 2023