Last updated: October 17, 2024

Article

Waging Peace: Eisenhower and the Korean War Armistice

Eisenhower Presidential Library

When Dwight Eisenhower ran for president in 1952, few issues—if any—were more pressing for the American people than the ongoing Korean War. For two years, the United States, alongside the United Nations, had been sending military personnel to Korea to fight against North Korean and Chinese forces in a battle of democracies versus communism. Just five years after World War II, which ended with the Korean peninsula divided into two countries, war erupted on the when communist forces poured into South Korea from the north. Buoyed by Soviet and Chinese support, the North Koreans aimed to unite the peninsula under communism, and to do so by force. The war quickly became a focal point for global tensions between democracy and communism, as United States and United Nations forces soon arrived to fight back. After two years of bloody combat, fighting had devolved into a costly stalemate by the time Eisenhower ran for president.

During the 1952 campaign, Eisenhower pledged that, if he was elected, he would personally go to Korea and find a way to bring the fighting to a close. Just weeks after he was elected the 34th President of the United States, Ike made that trip.

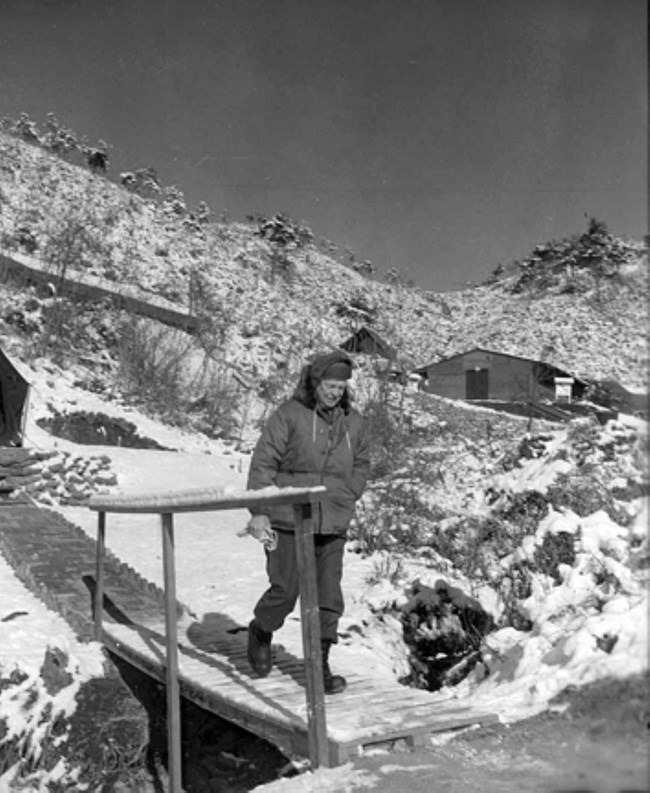

Eisenhower arrived on the Korean peninsula on December 2, 1952 after a laborious and complex 10,000 mile journey, spending three days visiting: soldiers, the front lines, and the South Korean capital Seoul. During this period, Ike also met with South Korean president Syngman Rhee, who pushed the new president-elect hard to launch an all-out assault on North Korean and Chinese forces. Rhee’s position would be unchanging throughout the rest of the conflict, and nearly sabotaged peace talks in 1953. The end of his Korea trip left Ike with the hard impression that the continuation of a stagnant line fighting could not continue. Eisenhower also came to believe that Russian and Chinese leadership respected only force. These impressions continued to shape the American position in the days and months to come.

After returning home and entering 1953, Ike found numerous obstacles in attempting to end the Korean conflict. Secretary of State John Dulles, a known hawk within the Eisenhower cabinet, ardently pushed for expanding the war and advocated for threating the use of atomic weapons. Dulles was not alone in this pursuit. General Douglas MacArthur, who had been fired as UN Commander in Korea by President Truman, gave Eisenhower the same advice, advocating in favor of using atomic weapons in Korea. Nuclear weapons, a recent addition to U.S and Soviet Union arsenals, had already been demonstrated to devastating effect on Japan during WW2. This debate showed the lingering effect of the United States use of these weapons at the end of World War II, and reflected fears that if the United States did not use them, the Soviet Union—having recently added them to their own arsenal—soon would. It also reflected a belief that nuclear weapons were the only way to get communist forces to negotiate an end to the war in good faith.

On March 5, 1953, Joseph Stalin--the leader of the Soviet Union-- died. Stalin's support had been a major motivating factor for the initial North Korean invasion into South Korea in 1950, setting off the conflict. Since then, Stalin had backed an aggressive approach to the conflict. He supported the entry of Chinese troops into the war in late 1950, after General MacArthur’s forces had crossed the 49th parallel and pushed close to the Yalu River, the boundary between North Korea and China. While China committed significant resources to the war, the fighting led to multiple issues for the Chinese government, including delaying the industrial buildup of the country, greater dependency on the Soviet Union, and the deaths of thousands of soldiers on the war-weary Chinese people. Stalin’s death brought not only a change in Soviet leadership but also attitudes towards the Korean War.

Stalin’s support had allowed the Chinese leadership to play a game of “brinksmanship” with the U.S., threatening the expansion of the war to avoid an appearance of weakness. After Stalin’s death, Soviet leadership ruled out supporting a broader war with the U.S., weakening the Communist negotiating position. Now, the Chinese were more willing to negotiate with the Americans.

While armistice negotiations had been ongoing at Panmunjom, North Korea, for two years, finally, 1953 saw progress towards a resolution. In addition to Stalin’s death, U.S. emmisaries had passed word that the Americans were considering a nuclear threat in Korea through Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru served as a third party to pass this message to the Chinese, letting them know that Eisenhower’s Administration was discussing multiple options to bring the fighting in Korea to a close.

Sensing movement toward an armistice, and the possibility that the war would not end with a united Korean peninsula under the control of the South Korean government, Syngman Rhee responded to these advances with indignation. Rhee expressed his dissatisfaction to the Americans, and event went so far as to conduct a massive release of Chinese POWs in an attempt to sabotage negotiations. Eisenhower and the Americans were furious, and indicated as much to the South Koreans, with Eisenhower telling Rhee, “unless you are prepared immediately and unequivocally to accept the authority of the UN command to conduct the present hostilities and to bring them to a close, it will be necessary to effect another arrangement.” In addition to Rhee, Dulles—along with other Republicans—pushed Eisenhower to reject the armistice, continue the fighting, and achieve a stronger victory over Communism in Korea.

By July, progress had led to hope for an agreement. Finally, on July 27, 1953—after three years of war, over 50,000 American deaths, and over three million Korean deaths—an armistice was signed bringing the fighting in Korea to a close. The armistice was not popular in Korea, where many wanted the country to be united again rather than permanently split into two. As historian David Halberstam wrote, “It seemed to be part of Korea’s national destiny to have little say about its own future.” Unlike eight years before at the end of World War II, the end of the Korean War was not greeted with parades and confetti, but with a mixture of relief, finger pointing, bickering, and exhaustion.

Despite the complexity of the peace agreement, both in how it was achieved and how it was received, Eisenhower saw the armistice as one of the proudest accomplishments of his presidency. He pushed against resistance from his own cabinet, his own political party, and the South Korean government to bring fighting to a close. Eisenhower’s visit to Korea left him with the belief that Americans were fighting and dying for little strategic gain in a long, bloody stalemate. Eisenhower believed limited war in a nuclear age was unwinnable, and unlimited war in a nuclear age was unthinkable. He was willing to endure political frustrations and invite criticism to stop the fighting in Korea. This push for a Korean armistice was the beginning of Eisenhower waging peace rather than war during his eight years as president.