Last updated: February 27, 2023

Article

Eisenhower and NASA

Eisenhower National Historic Site

Whether through manned spaceflight or unmanned rover programs, American explorations of space continue to expand our scientific knowledge. As a nation we’ve pushed through the boundaries of the Earth’s atmosphere, explored other planets, and have even left our solar system. Nearly every American alive in 1969 remembers the wonder and excitement of the first moon landing, one of the greatest scientific achievements of the twentieth century. All of these accomplishments, and more were pioneered by NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, which was created by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1958.

Prior to the creation of NASA, the United States had taken an interest in scientific exploration and innovation, but demand for a national agency on space related innovation was closely tied to growing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union following the Second World War. The first American rocketry programs were operated by the Department of Defense with a goal of ensuring American dominance in space. In response, the Soviet Union developed and announced a rocketry program of their own, and on October 4, 1957 launched Sputnik 1 into orbit. Sputnik 1 was the first manmade object to enter orbit, and with both nations experiencing urgent need to demonstrate international dominance within and beyond the Earth’s atmosphere, the Space Race began.

Fear of Soviet technology and scientific advancements accelerated an American response to the launch of Sputnik 1. The United States Navy tried to launch their own satellite, the Vanguard TV3, which lost thrust two seconds after the launch and exploded shortly thereafter. With the success of their adversaries and the failure of their own rockets, America began to formulate a new, long-term space plan. Even though the United States Army successfully launched Explorer 1 in January 1958, it was clear that the American rocketry program needed to be restructured and revamped.

On April 2, 1958, President Dwight Eisenhower, aware of the social and political scene unfolding around dominance in outer space, wrote a special note to Congress calling for the creation of a civilian National Aeronautics and Space Agency. As an experienced general himself, Eisenhower knew the importance of separating military from civilian life. It was necessary to keep the agency civilian run, he wrote, because “space exploration holds promise of adding importantly to our knowledge of the earth, the solar system, and the universe, and because it is of great importance to have the fullest cooperation of the scientific community at home and abroad in moving forward in the fields of space science and technology. Moreover, a civilian setting for the administration of space function will emphasize the concern of our Nation that outer space be devoted to peaceful and scientific purposes.”

Furthermore, a civilian agency would reduce the rivalry between the various branches of the military. Since the Army, Navy, and Air Force all had rocketry programs, there was competition amongst them for funds, favor of public opinion, and personnel. As such, their disparate programs were often counterproductive and costly. Under a unified civilian space agency, projects that were non-military and strictly scientific in nature would be administered by a centralized authority, eliminating competition within agencies.

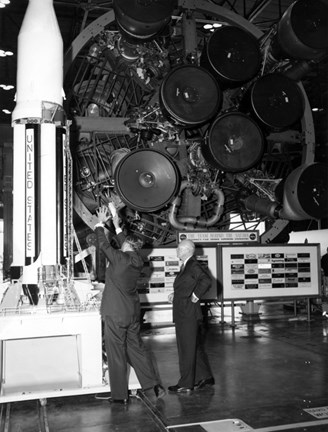

On July 29, 1958, President Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act into law, formally creating NASA. On August 8, he nominated T. Keith Glennan to be the first administrator of the newly created agency. Shortly after, the Department of Defense agreed to transfer all nonmilitary space projects to the newly formed civilian organization, ensuring there was a clear differentiation between military and scientific space operations; a distinction that still remains today. By 1960, NASA took command of the Army’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory headquartered in Pasadena, California, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency located in Huntsville, Alabama, and the Navy’s Vanguard Group. This consolidation led to the cooperation of several significant scientific minds, most notably Wernher von Braun, who would later lead NASA missions to land on the moon.

Despite the civilian nature of his new agency, President Eisenhower still placed emphasis on success of military space-related programs and projects. On December 19, 1958, Dwight Eisenhower became the first man to have his voice broadcasted from space, which was done via a military rocket. An Air Force Atlas Missile launched a satellite containing a tape recording of the president’s voice, sharing “America’s wish for peace on earth and good will toward men everywhere.” The Air Force missile used to broadcast this presidential message is of the same type that could have been utilized to transport a thermonuclear warhead. The decision to utilize the Air Force Atlas rocket rather than NASA rockets reflects the severity of Cold War tensions that still permeated the American space program, despite the creation of a civilian agency, and demonstrates the balancing act between civilian and military space projects during the late Eisenhower Administration.

While the development of military rockets and space projects continued, it was through NASA that the future of manned spaceflight progressed. As the agency continued to develop, the space program flourished. In April 1959, the “Mercury Seven,” were introduced. These seven military pilots would be the first Americans to travel into space. Project Mercury got off the ground a few months after President Eisenhower left office and retired to Gettysburg, but credit for its success is often attributed to him.

Four months after his death, and eight years after he left the Oval Office, man landed on the moon and the civilian space agency created by Dwight Eisenhower truly made an iconic impression on the citizens of this atmosphere, and beyond. Out of Cold War tensions, NASA was born, and continues to push our nation (and others) to explore the “final frontier.”