Last updated: February 3, 2022

Article

President Eisenhower and Civil Rights

The aftermath of the Second World War saw the world changed forever. The conflict illuminated to many around the world what was wrong with prewar societies and those people who had survived the conflict were strengthened with a new sense of self and purpose. African Americans who had served their country during the war were no longer willing to accept living in a country that saw them as second-class citizens. The “Double V” campaign was born around the idea of victory not only in war but at home over racism and inequality. The 1950s would see a dramatic push for equality across the nation.

Civil Rights was a polarizing topic across the country as post-war attitudes on racial equality and inequality began to change across the country. The Eisenhower administration was certainly aware of these currents and because the topic was on the minds of voters, it was a movement that Eisenhower and his staff could not ignore.

When Eisenhower entered office, there were already two important Civil Rights issues at hand. First, Eisenhower continued President Harry Truman’s orders to desegrated the federal workforce and the armed forces. This process was essentially finished by the end of Eisenhower’s first year in office. The second and perhaps more important element was in the hands of the Supreme Court. When Eisenhower became the 34th President, the Brown vs the Board of Education case was already before the Court. Ultimately, it would become the landmark Civil Rights case of the 20th century.

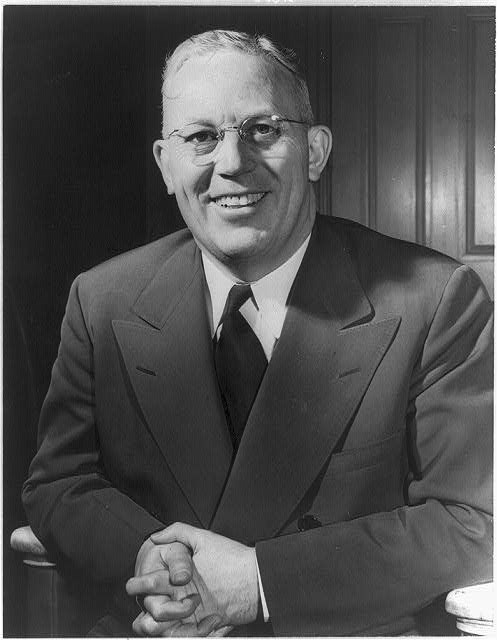

Eisenhower would have a major impact on Brown vs. Board through two important appointments. The first was in his choice of Attorney General, Hebert Brownell. Brownell was a supporter of civil rights and in his brief argued that any state mandated inequality that came about from segregated schools was unconstitutional and a violation of the 14th Amendment. Brownell was also instrumental in helping Eisenhower make judicial appointments, including his most important one.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

When President Eisenhower appointed Governor Earl Warren to the Supreme Court as Chief Justice, it began a new era for the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Warren authored the Brown vs. Board decision in 1954, stating the court’s unanimous decision declaring state laws segregating schools were unconstitutional regardless of whether the segregated schools were equal in quality. The decision was a boon to the Civil Rights movement and one of the most important cases in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court.

After these major accomplishments early in his presidency, Eisenhower’s administration seemed to lose steam regarding Civil Rights. Eisenhower himself was criticized for not making a stronger show of support for the Civil Rights movement or even the Brown vs. Board decision itself. After the Brown decision was announced, Eisenhower said “The Supreme Court has spoken, and I am sworn to uphold the constitutional process in this country; I will obey.” This somewhat ambiguous statement has been interpreted as sign that Eisenhower was either for or against Brown and the broader Civil Right movement. Eisenhower kept his personal thoughts on the matter relatively quiet and continually dodged chances to make a strong statement either way.

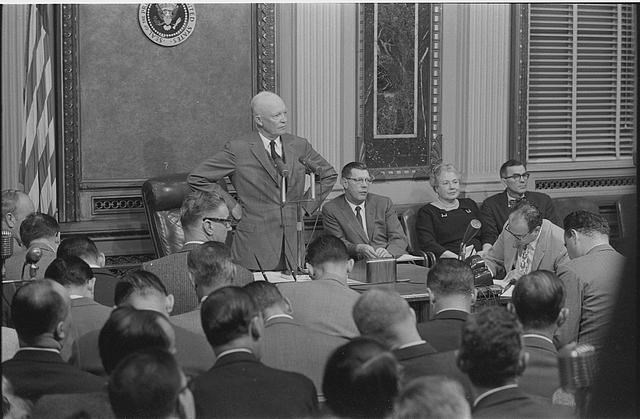

While keeping his personal thoughts quiet, with the support of Brownell, Eisenhower was determined to push through a Civil Rights bill. The groundwork was laid during his first term in office, but the bill would eventually pass in his later years in the White House. During his State of the Union in 1957, Eisenhower emphasized the four points this bill would contain. It would, first, create a bipartisan congressional commission to investigate civil rights violations. Second, the bill would create a Civil Rights division in the Department of Justice under a new Assistant Attorney General. Third, it would empower the Attorney General to pursue contempt proceedings against anyone who violated civil rights stemming from the 14th Amendment and finally it would empower the Attorney General to do the same in connection with a violation of voting rights as laid out in the 15th Amendment.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

This proposal was met with immediate backlash from Southern congressmen and the bill that would eventually reach President Eisenhower’s desk was very different from the bill as it was first proposed. Sections 3 and 4 were essentially gutted. Eisenhower and his administration were devastated. Still, it was the first Civil Rights legislation in over eighty years. If nothing else it was a step in the right direction, a sign that times were changing.

At the same time Eisenhower was signing the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the last major Civil Rights event in Eisenhower’s presidency was beginning to unfold. In response to Brown vs the Board of Education, the Little Rock school board in Arkansas had decided on a plan for integration starting at the high school level and then slowly moving downwards. It was decided that black students would be allowed to attend Central High in the Fall of 1957. When the school year started, a white mob and the national guard blocked the students from attending. The crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas, where nine black students were denied entry to Central High School would showcase what kind of leader Eisenhower was. At first Eisenhower was reluctant to intervene. He saw little benefit in the president involving himself in direct conflict with a governor. In meetings with Arkansas’s Governor Faubus, Eisenhower left feeling that Faubus would resolve the conflict upon his return to Arkansas. When Faubus continued to deny entry to the students and the Little Rock district court handed down an injunction against him, Eisenhower then had the clear authority to act. He signed Executive Order 10730, which sent Federal troops from the 101st Airborne Division to stop the injustice that was playing out at Central High in Little Rock.

Eisenhower left the presidency with a rather cloudy reputation on Civil Rights. In the words of historian William Hitchcock, “Again and again on civil rights he expressed “moderate” opinions in the face of men whose views were immoderate. He sought gradual changed where others sought immediate progress or not at all. He showed dispassionate common sense; his opponents fought with passionate zealotry.”

For many reasons both personally and politically, Eisenhower could not be the leader that many people yearned for. Still, his administration marked a turning point in the Civil Rights movement. It reflected a society that was on the verge of change but was still turning the wheel of progress. His Supreme Court appointments had an impact that continued after his presidency, as did his actions in promoting the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and his intervention with the 101st Airborne Division during the Little Rock Crisis.

Suggested Reading:

Brownell, Hebert with John Burke. Advising Ike, the Memoirs of Attorney General Heber Brownell (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1993)

Hitchcock, Williams. The Age of Eisenhower (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018)

Nichols, David A. A Matter of Justice, Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007)

Calling all teachers!

For a lesson plan exploring President Eisenhower's actions in the 1957 Little Rock Crisis, click here.

Tags

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- dwight d. eisenhower memorial

- eisenhower national historic site

- little rock central high school national historic site

- eisenhower national historic site

- general eisenhower

- president eisenhower

- dwight d. eisenhower memorial

- civil rights

- civil rights act of 1957

- little rock central high school national historic site

- little rock

- brown vs board

- eisenhower

- president

- article