Last updated: October 23, 2022

Article

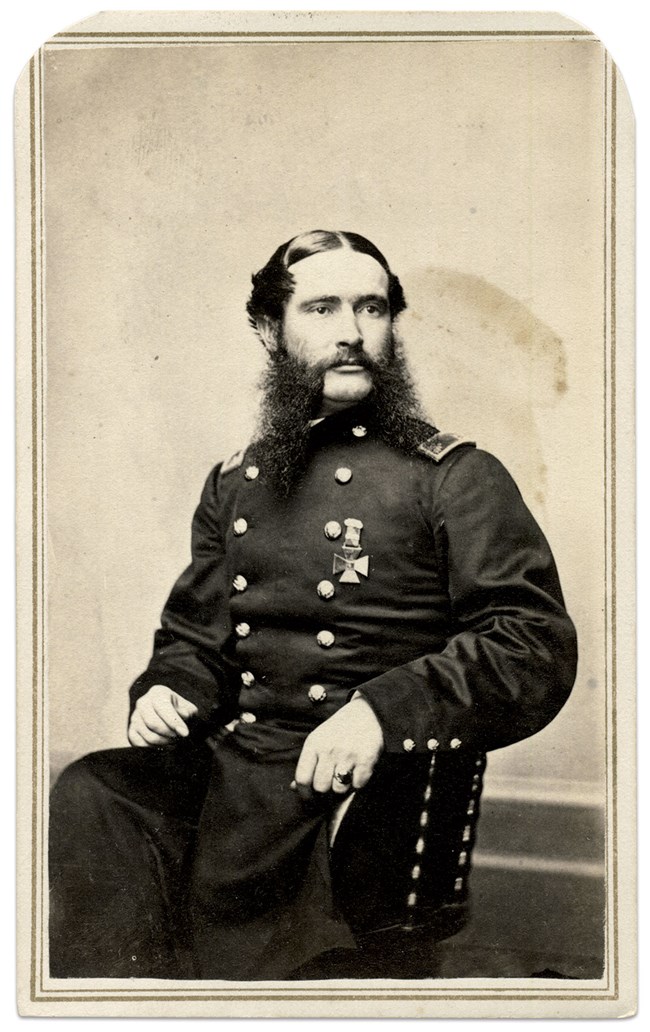

Captain Edward Hill and the 16th Michigan Volunteers

NPS Photo

Photo courtesy of Rick Carlile

Two Years of Hard Fighting

Edward Hill was born April 13, 1835 in Liberty, New York, to Betsey Hill. His father’s name is unlisted on his death certificate. At some point the Hill family moved to Michigan, and on December 14, 1861, at age twenty-seven Hill enlisted in company D, Lancers at Detroit. The Lancers, a cavalry unit organized by a colonel in the Canadian militia, Arthur Rankin, was an unusual outfit. Its men were to carry long-shafted wooden spears in addition to sabers, carbines and pistols. Since the Lancers were founded by a Canadian and war with England seemed possible, there were reservations in the government about approving its organization. In February 1862, before the Lancers left Michigan the War Department broke them up into two companies of infantry and two smaller detachments. The recruits of Lancer Companies D and E, including Edward Hill, were assigned to an independent Michigan regiment that had been organized in September 1861 by Colonel Thomas W. Stockton, a West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran. Stockton’s regiment was shortly afterward designated the 16th Michigan and sent to join the Army of the Potomac.

On March 20, 1862 Hill was officially mustered out of the Lancers as a 2nd Lieutenant, then commissioned four days later into company K of the 16th Michigan Infantry. This regiment was assigned to the Third Brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, which was then commanded by General Fitz John Porter, and they remained there (under various commanders) until the end of the war. By then, the men of the Sixteenth had become veterans of some of the Civil War’s most important and bloodiest campaigns. Attached to the Army of the Potomac, they took part in the Peninsular Campaign under General McClellan, including the siege of Yorktown and a battle at Hanover Court House in May 1862. On June 27, 1862 the Regiment fought a desperate battle in front of Richmond at Gaines’ Mill. Confederate General Robert E. Lee assaulted Porter’s reinforced army of 34,000 with a force of 57,000 men, finally forcing Porter’s men to withdraw across the Chickahominy River. At Gaines’ Mill the Sixteenth suffered 49 men killed, 116 wounded, and 55 missing. Four days later, during the retreat of McClellan’s army to the James River, the Sixteenth prevented a Confederate charge from succeeding at Malvern Hill.

Given little time to rest, the Sixteenth was transferred to northern Virginia at the end of the Peninsular Campaign and on August 30, 1862 participated in the Second Battle of Bull Run. There the regiment faced heavy fire in an advance on a Confederate battery and took serious casualties. Among the wounded was First Lieutenant Edward Hill, who had been promoted after the struggle at Gaines’ Mill, but the wound apparently healed quickly and Hill rejoined his regiment within weeks.

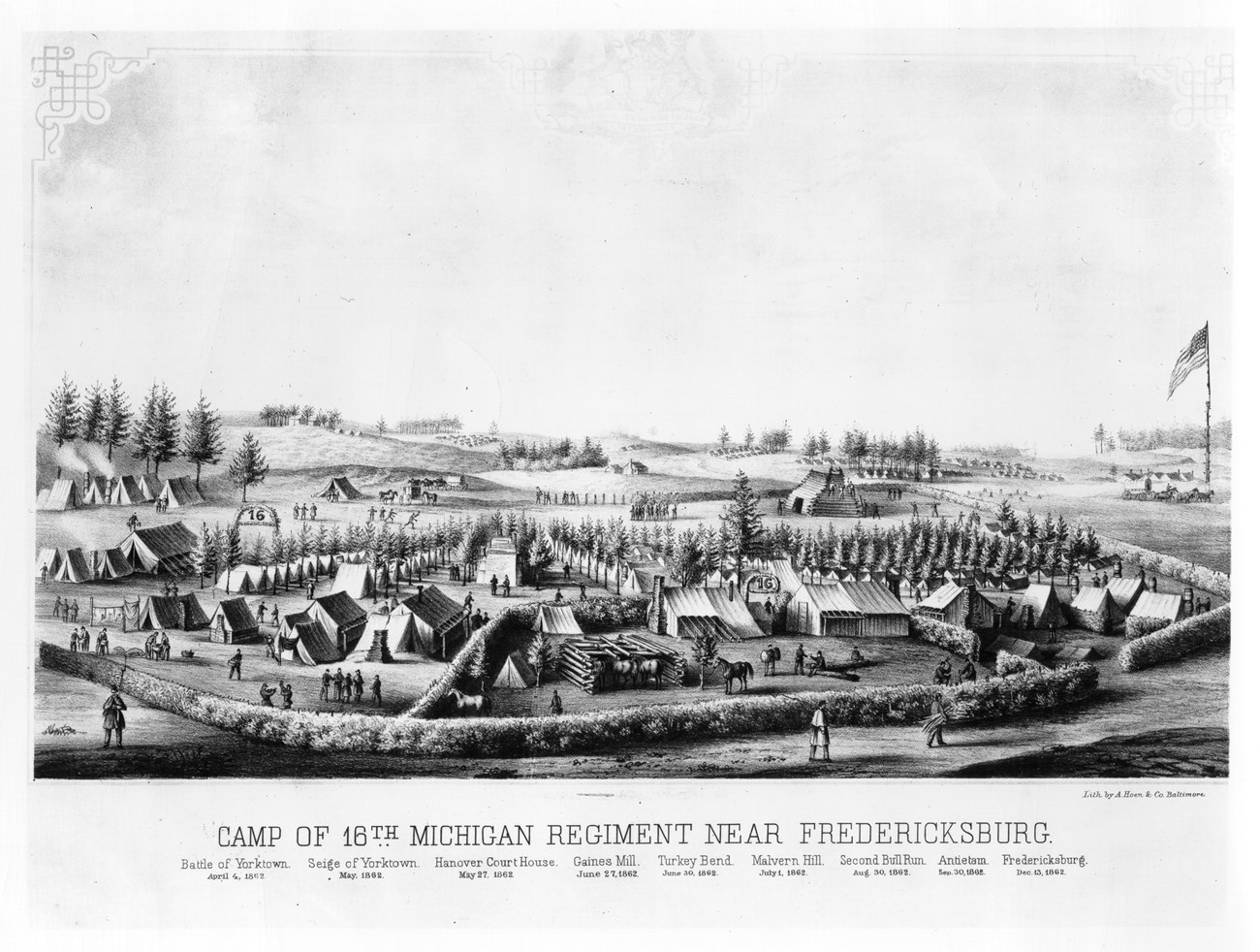

The toll continued as the 16th Michigan fought in nearly every major battle undertaken by the beleaguered Army of the Potomac under its successive commanders. At Antietam in September 1862 the regiment was held in reserve but used to pursue Lee’s retreating Confederates across the Potomac River. At Fredericksburg in December 1862, the Sixteenth was one of the last Union units to cross the Rappahannock and advance on Confederates waiting behind earthworks at the heights above the town. Their attack was repulsed, and the survivors were forced to spend twenty-four hours lying on the field until they were ordered to retreat under cover of darkness. In the commanding officer’s report, Lieutenant Hill was commended for his bravery, as he had also been at Malvern Hill.

At Chancellorsville in May 1863, the Sixteenth was not involved in heavy fighting, but they made up for it the following summer during the Gettysburg campaign. At Middleburg, Virginia, on June 21, 1863 the 16th Michigan pushed back J.E.B. Stuart’s brigade, which was screening Lee’s northward push into Maryland and Pennsylvania. On the second day of the climactic Battle of Gettysburg, men from the Sixteenth joined others from the Third Brigade for the desperate, and ultimately successful, Union defense of Little Round Top, one of the pivotal moments of the entire war. Although part of the regiment’s line broke, most of the men, including Hill, remained at their critical position near the southern end of the Union line. After Gettysburg, the Sixteenth was constantly on the march, maneuvering for position against the Confederates in northern Virginia and occasionally skirmishing with them. The Michigan men managed to capture the Confederate defenses at Kelly’s Ford on the Rappahannock early in November 1863 and remained there until Thanksgiving. In General Joseph Bartlett’s report on this battle at Rappahannock Station, Captain Hill and his skirmishers were praised for charging and entering the enemy’s works.

In December 1863, with two years’ service completed, over 90 percent of the Sixteenth’s veterans—more than 260 men—re-enlisted for three additional years, including Captain Edward Hill, who had been promoted in April 1863. The regiment was allowed to return to Michigan on a veteran furlough of thirty days. At its end, the men gathered in Saginaw on February 17, 1864, fortified by the addition of nearly 150 new recruits.

Courtesy Archives of Michigan

To the Virginia Front

The end of the Michigan furlough is where Hill’s journal begins. "Will leave to morrow," he wrote on February 16, 1864. A send-off dance marked the occasion: "Ball at Webster House to night in honor of the 16 Regmt, My Partner beautiful Lady from Cincinnati Miss Elvira Ward. Every thing passed off agreeably." The next day the regiment’s travel began. They left Saginaw and that night arrived in Detroit. From there, the trains took them to Toledo, Cleveland, Erie, Dunkirk and Elmira in New York, then south through Harrisburg and on to Baltimore, where the regiment was detained for twenty-four hours. Hill’s diary entries detailed the delays and difficulties of his trip, in which he joined the other regiment officers.

On February 22 the men stayed in Washington, and on the next day they left for the front. At the headquarters of their division two miles from Bealton Station they began building cabins for their winter camp. While Hill’s men set up camp, Hill enjoyed a whirlwind of social calls and theater in Baltimore and Washington. In Baltimore he attended a military dress parade, called often on friends, and went with them to see the celebrated Mrs. D.P. Bowers perform in two hit plays based on sensational Victorian novels, Lady Audley’s Secret and East Lynne. "At Baltimore good times these," he summarized in his journal.

Back in Virginia, the regiment’s men spent their time grading camp roads, building cabins and putting fences around the camp, performing picket duty, guarding the railroad line, and drilling the new recruits until mid-March. These activities were not glorious but there was always the threat of a surprise attack by enemy forces. Until General Grant arrived to take charge of the Union forces, much time was used for rifle drills and other preparations for the fight.

Captain Hill, meanwhile, left Baltimore for Washington for some unspecified medical treatment, which began on March 2 and probably allowed him several weeks leave. He took full advantage. Although there are gaps of more than two weeks in his diary during mid-March and again in early April, its entries detail some of his socializing at the capital. Hill’s fondness for the theater was gratified by the presence in town of two of America’s most famous actors. Early in March he was able to see Edwin Booth in signature roles as Richelieu and Richard III, and a few weeks later he watched the venerable Edwin Forrest perform as Richelieu and Damon. Other entries speak of social calls, playing billiards, and "a sunset walk in the evening with Madam Adelina," who also hosted "a magnificent supper" as a parting present for Hill.

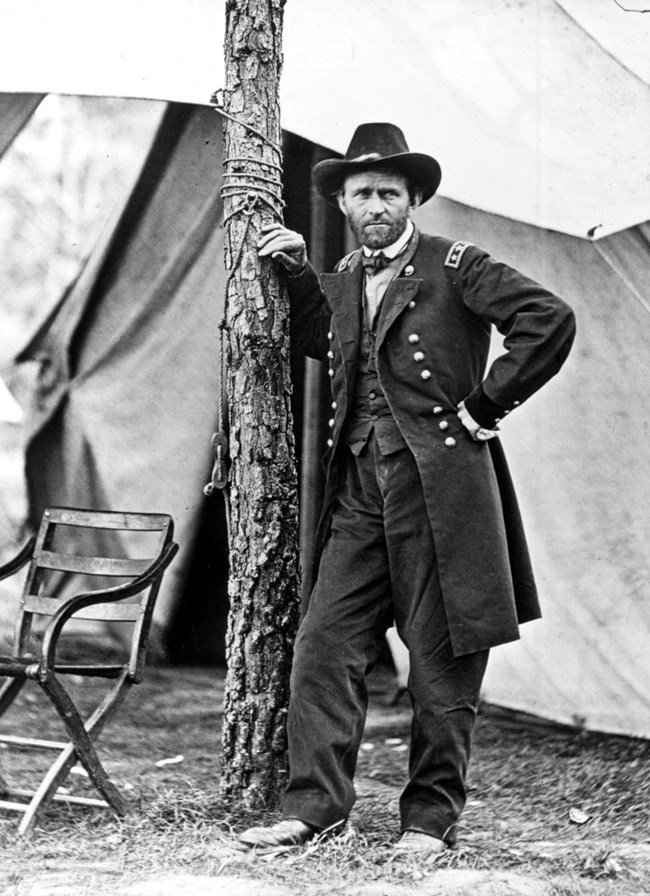

On April 16 Hill finally packed for Virginia. Again there are two weeks without diary entries as Hill mingled with the men of his company and set up his cabin at camp. General Grant, meanwhile, was finalizing plans for a mighty spring offensive. The massive Army of the Potomac, with about 115,000 men, was to move south across the Rapidan River and stalk the 64,000 men of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Grant hoped to force Lee into open combat away from entrenched positions as the Confederate general moved his defenses or retreated to protect Richmond. This relentless campaign would eventually take nearly a year and cost more than 100,000 Union casualties.

Library of Congress

The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and North Anna

The Army of the Potomac’s Fifth Corps was now commanded by General Gouverneur Warren, and the Corps’ First Division was led by General Charles Griffin. Hill’s entry for May 3 notes how abruptly its schedule switched from recreation to war: "Played Ball with the 44th. They beat the 16th badly. Marched to day toward Culpepper." The fun and games ended when "strike tents" sounded at 11 p.m. and the regiment began marching two hours later to Culpepper, through Stevensburg, and onto to a plank road that led them to the Rapidan River. At 10 a.m. on May 4, they crossed the Rapidan at Germanna Ford. Hill noted the significance of the date: "One year ago to [day] we were getting out of Chancellorsville 2 years ago the Rebs got out of Yorktown " The regiment turned off on the Gordonsville Road, marched around in the woods, and bivouacked. They had arrived in the Wilderness.

There the first battle of the Virginia Campaign began. On May 5, 1864, when Grant ordered an attack, two days of vicious fighting broke out in woods so thick and smoky that soldiers fired blindly and wounded men burned to death in the flaming underbrush. On the first day of the battle the 16th Michigan was sent to guard a supply train and thus was largely removed from the fighting. Hill heard about Union losses the next day: "our Brigade lost heavily yesterday 5 o clock surrounded and apparently cut off 6th Corps broken, I fear a rout." On May 6 the Sixteenth rejoined the Third Brigade on the front, although at first the men were kept in reserve. Later, they advanced on the enemy and were involved in heavy skirmishing. "Finally this morning arrived at the front at 6AM, terrible fighting going on all along the lines," Hill reported. The next day the men of the Sixteenth were sent forward to find the enemy and take rifle pits, but eventually fell back. By four o’clock Hill was "sitting behind a trim tree all sliced by cannon shot and musketry." "The old 16th has fought well today," he wrote, understandably overestimating the killed and wounded, which officially numbered seven dead and thirty wounded.

The Battle of the Wilderness had ended, the Sixteenth’s Captain Charles Salter noted, "without being able to accomplish much (except to get immense numbers of men killed and wounded)." The Confederates had lost about 11,000 men while the Union army lost about 18,000. Lee had fought off Grant’s larger army, but unlike previous Union commanders Grant had no thoughts of retreating. He ordered a continued push south in hopes of turning Lee’s right and placing his army between Lee and Richmond.

Secrecy was necessary so that Grant’s forces could arrive at its next destination — Spotsylvania Court House — before the enemy. Lee, however, anticipated Grant’s move, and when the Union advance guard arrived they found Confederate General Anderson’s men already entrenching. On the morning of May 8 Anderson repelled an uncoordinated Union attack.

Secrecy had been effective at least within the Union army, for Captain Hill was surprised by the Union’s move. When Hill was relieved from picket duty at 2 a.m. on the 8th, he "found every thing had been moved," so he rushed to follow the column toward Spotsylvania. Since the Sixteenth was the rear guard for the move, they were not involved in the beginning of the battle at Spotsylvania. However, while moving to their assigned position at the front they ran into a swamp, where the delay led them to a vicious nighttime confrontation with the enemy. "Battle raging heavily—Col Locke wounded," Hill reported. Fourteen Michigan men died in the encounter and nearly fifty were wounded.

On May 9th the Confederates busily erected an inverted U-shaped five mile line of breastworks around Spotsylvania Court House. The Sixteenth was ordered to the Union breastworks, but then was sent to the rear as defensive skirmishers whose other job was to round up stragglers. Hill’s journal recorded the skirmishing and reported only by hearsay on the general Union charge in front, believing it a success but acknowledging that it "cost many men."

Thinking that the Confederate center was exposed, Grant ordered two attacks on the center of the Confederate line on May 10 to cut it off from the main army. The first attack failed; the second briefly broke through, but since was no reinforcing support the Union troops were driven back. Ordered to the trenches, the Michigan men were with Warren’s Fifth Corps on the front line all afternoon, where they did not charge but did encounter heavy musket fire. "Fighting still continues. A hard fight to day. The 16 in the Rifle Pits in front a hot fire all day. Corpl N Dennison and Private White of my Co wounded. . . . I believe all is going well." Finally at 9 p.m. they were relieved and allowed to bivouac behind the lines for the night.

The next day, May 11th, the Michigan men were sent back to the breastworks and again engaged in heavy rifle fire. Hill was exhausted. "7th day of the fight, will it bring rest[?]" "The old 16th in the Rifle Pits again – much strengthened last night. Sharp firing and some shelling all day—suffered a thousand narrow escapes. Bivouwacked at 10 o clock."

Grant still believed that the protruding center of Lee’s defenses was vulnerable, and he planned a surprise attack to begin at dawn on May 12th. The men of the Sixteenth were awakened at one in the morning and marched rapidly in the rain as Grant prepared the day’s assault. Union troops advancing on the right took horrific casualties, but the Sixteenth, which had been moved to the left near the Po River, was largely spared. Around noon, the Michigan men were sent into the breastworks and ordered to charge, but the order was soon rescinded. "Still the battle terrifically rages," Hill recorded. "When will the end come[?]" The fighting did not stop until after midnight, and even then the men of the Sixteenth slept on the battlefield at the ready. The single day’s casualties totaled nearly 7,000 on each side. Grant had again failed to break Lee’s defenses, but he promised to "fight it out on this line if it takes all summer," he told President Lincoln.

After the Battle of Spotsylvania, Grant continued to look for weak spots in Lee’s lines during a week of maneuvering. Half of his army was ordered to swing around the Confederate right, then countermarched for an attack on their left. Hill’s entries of May 14 and 15 provide a mirror image of the maneuvering: "Rained all night. Marched 7 miles through the mud last night to the left Joined Burnsides forces," and "Rained all night. Moved rapidly to the right, and formed a junction with Gen Burnsides forces." When these moves yielded few results, Grant tried one more assault on the Confederate lines. On the moonlit night of May 17 the Michigan men and a few other regiments were "marched noiselessly to the front" (as Hill wrote) and ordered to dig trenches within a half mile of the Rebel lines. The next morning, according to Hill, "the fog rolled off and disclosed the Rebels with their strong works." The surprised Confederates opened an artillery fight which raged over the heads of the troops in the trenches, creating "a terrible shelling along the whole line." A Union assault farther down the line was repulsed.

Library of Congress

The Fifth Corps managed to cross the North Anna River on May 24 and withstood a surprise Confederate attack by a smaller force under General Cadmus Wilcox. They cleared just enough room in the next two days to set about tearing up the Virginia Central Railroad, which ran parallel to the river. Some of the Michigan men dug rifle pits, while those on skirmishing lines suffered some casualties. "Lost 3 men killed and wounded in the fornoon," Hill reported on the 26th. By this time Grant realized that the Confederate position near the North Anna was too formidable, and again he ordered a long flanking move to the southeast. After supper, the Sixteenth "fell in at 8 o clock P.M. for an all night march," Hill recorded on the night of May 26. "Issued 2 days rations to the men." The next day was "the first day in nearly a month that we have had no fighting," Hill wrote, but there was little relief, since the regiment marched nearly thirty miles east, then south, toward the Pamunkey River. The countryside was pretty and the plantations well cultivated, but "the Division straggled very much on the march in consequence of much rapid marching and excessive duty for days previously." On May 28th the regiment crossed the Pamunkey River near Hanovertown. The Union and Rebel cavalry fought an indecisive battle at nearby Haw’s Shop while the federal infantry continued to cross the Pamunkey. Hill was aware of the day’s significance. "The Cavalry holding the enemy in check 4 miles in front, we have secured The Position and are within 15 miles of Richmond," he wrote on the night of the 28th, his excitement accentuated by the underlining.

As at the North Anna, Lee had drawn a strongly entrenched defensive line facing east behind Totopotomoy Creek. So shortly after his army crossed the Creek, Grant again shifted them south. "We are advancing in the direction of Gains Mill," Hill reported, "and appear to be in the extreme left flank of the Army." Two years earlier, the regiment had experienced its first severe fight in this neighborhood during McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign.

The men of the Sixteenth realized how close they were to Richmond and knew that they would have to fight to advance further. For his part, Grant was running out of flanking room and would have to consider a direct attack. Lee, blocking the roads to Richmond, thought the same way and sent General Jubal Early’s division to attack the Fifth Corps’ left. On the morning of May 30 Early’s men charged into the Fifth Corps’ left flank near Bethesda Church. The Second Brigade was sent to meet the attack, as Hill’s diary notes, and in the afternoon the 16th Michigan was ordered to move up to support them. They formed a line under heavy fire and sent out skirmishers into an open field, where they were exposed to crossfire by Rebel sharpshooters. Major Robert Elliot was struck as he arrayed his men, and ten other Union soldiers were killed or wounded, but the Michigan men held their ground until the Union artillery arrived to halt the Confederate attack. "A hard fight today," Captain Hill recorded tersely in his diary back at the Union breastworks, "old 1st Div. doing admirably." "Poor Maj Elliott mortally wounded," he lamented. The next day’s entry confirmed Elliott’s demise. "The gallant Major Elliott is dead," Hill wrote, "died last night at 6 o clock. Peace to his ashes."

On the whole, however, May 30th had been a good day for the Union forces. Warren’s men had pushed back the Confederate Second Corps, allowing the army’s southward shift to continue. Grant moved forward with his plan to mass the Union forces three miles south of Bethesda Church at Cold Harbor, the next major crossroads that led west to Richmond.

Wounded at Cold Harbor

It was General Sheridan who seized Cold Harbor, a dusty, dreary intersection of great strategic importance. If Union forces held it they could use several routes to get to Richmond or to maneuver behind Lee's forces. Once the bulk of the Army of the Potomac arrived at Cold Harbor, Generals Grant and Meade would consider offensive moves. Meanwhile, on May 31 they planned to stay on the defensive unless the Confederates pushed east to divide the main Union divisions that were moving south. The 16th Michigan remained in position north of Cold Harbor, engaged in skirmishing and an advance upon some Confederate forces who were attempting disrupt the Union move. "Advanced in line upon the Rebs right flank," Hill reported, although there was apparently no firing. "I have charge of the left wing of the Regiment. 3 P.M." Enough of a lull occurred for Hill to change his shirt for the first time in a month.

As both sides began massing troops in the area, a major battle was brewing. Meanwhile, the two armies watched each other and made forays to test each other's strength. On the morning of June 1st, the 16th Michigan was ordered to move west from their position two miles north of Cold Harbor, advancing as skirmishers ahead of their division. The terrain included a bottomland woods called Magnolia Swamp. Captain Hill's job in leading his men was to "press the enemy and draw their fire" to determine their strength and hidden artillery positions. The Michigan men drove the Rebel skirmishers back, captured two lines of their rifle pits, and resisted a fierce counterattack after being resupplied with ammunition. It was an exhausting day of fighting, costing the regiment at least thirteen wounded. One of the casualties was Captain Hill, who described the day's events succinctly in his diary: "I had charge of the Picket line on the left. This morning the 16 ordered to advance, carried the enemies rifle Pitts and advanced to the brow of the Hill, when I was shot in the right thigh."

Hill referred to the bullet's entry point as his right thigh, but it was somewhat higher up on his hip; medical reports later referred to it as a "gunshot wound of right ilium," or pelvic bone. The wounded captain was placed on a stretcher and taken to a makeshift field hospital, where he was examined and, according to Private Jack Wood, "left to die." Wood was sent to gather Hill's personal effects and take them to regimental headquarters to be returned to his family. The view that Hill was dying was so widespread that Captain Salter of the Sixteenth reported it in a letter to a friend: "Our Regt lost this day Capt Hill mortally wounded." Captain Hill's closing words in his diary made it appear he was of the same opinion. Believing it would be his last entry, Hill recalled his beloved Shakespeare. His entry, "Alas poor Yorick," refers to the churchyard scene in Hamlet where a gravedigger exhumes the skull of a deceased court jester and Hamlet voices a meditation about the fleeting vanity of life on earth.

Still breathing the next day, Hill knew that his physician expected him to die: "Suffered terribly from my operation yesterday the ball having passed through the flesh of the hip going also entirely through the Ilium bone from this point the surgeon has been unable to trace it but I know what he thinks. He thinks that it has passed into the bowels and that I will die."

Meanwhile, the battle at Cold Harbor continued. Believing the Confederates had not yet fully entrenched, Grant sought to seize the opportunity and attack on June 2nd , but delays in troop movements postponed the assault. The next morning the Union commanders hurled their men against the Confederates awaiting them behind well constructed breastworks. The horrendous fighting of June 3 left 7,000 Union soldiers killed or wounded and disabled only 1,500 Confederates, a ghastly Union defeat. The 16th Michigan, which remained in position near the Bethesda Church, escaped involvement in the main assault at Cold Harbor. Still, the regiment had endured more than thirty fatalities and 120 other casualties since crossing into the Wilderness a month earlier.

While Hill suffered from his wound, Grant's men continued in their quest to wear down Lee's army. After the disastrous losses in Cold Harbor, Grant swung his army south again, this time crossing the James River and moving on Petersburg, a railroad center south of Richmond whose capture would force evacuation of the Confederate capital. Once again, hesitations and confusion in the field delayed a Union attack on lightly manned fortifications, and Grant's troops settled down for a long siege and encirclement of Petersburg. The 16th Michigan, which had been used to screen the James crossing, did not reach the Petersburg area until June 16th. They were engaged in the next two days' assaults on Petersburg's defenses, remained in the Union trenches until late July, and spent the fall fighting to extend the Union lines westward. Grant's siege would last nearly ten months: not until April 1865 would the Union forces finally stretch the Rebel lines to the breaking point and compel Richmond's evacuation.

To his own surprise and his doctor’s as well, Captain Hill did not die of his rifle wound. His journal continues after Cold Harbor and is filled with updates on his condition. At the field hospital, Hill’s friend Jack Wood of the Sixteenth administered "stimulants"—probably whiskey—to dull the pain and arranged for an army wagon to take Hill to White House Landing on the Pamunkey River. Hill suffered excruciating pain on the wagon journey to the wharf at White House, where Wood placed him on a steamer bound for Washington. His prospects improved once he arrived at Armory Square Hospital on the National Mall. There he rested comfortably and Dr. Willard Bliss, the Michigan surgeon in charge, decided not to risk probing his wound but simply to let it heal.

Some of Hill’s nights were "wretched" and fearful, but his improvement was obvious. The diary chronicled his steps toward mobility. "Feel better to day," he wrote on June 20, when Jack (probably still Jack Wood) "wheeled me about the floor a little for the first [time]." The next day he "went out for the first time . . . in the Hospital chair." Hill recognized his progress and was gratified by it: "Expect am safe in saying that I am gaining slowly," he wrote. "Every day is a great desideratum." Within ten days of his hospitalization he was writing and receiving letters.

Hill’s days were brightened by a steady flow of visitors, who bore gifts of berries and brandy as well as towels and eating utensils. Some were apparently old friends, like the Houserights of Washington. Mrs. Houseright was so helpful that Hill was effusive in his praise for her and apologetic after an argument between them. Other callers were military colleagues who were also wounded or on leave. "About 6 Friends call on me and keep my spirits pretty well as I do theirs I don’t know which," Hill wrote after one such visit. From army friends and the newspapers Hill picked up snippets of war news—that Grant’s army had crossed to the south side of the James River, for example, and that the Union navy had finally put the Confederate raider Alabama out of commission. In mid-June a Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin, apparently relatives of Hill, made a surprise four-day visit accompanied by other family members. Especially notable was a visit from "Libby" Custer, the wife of the flamboyant young Union officer from Michigan, George Armstrong Custer.

On July 2 Hill moved to private rooms away from the hospital. He found his new quarters "home like" and wrote after his first day there that he "never passed a happier day in my life." Still, away from the hospital the flow of visitors slowed down and along with it the buzz of gossip and war news. "How commonplace every thing is becoming in my Diary," Hill complained resignedly on July 5th. "Nothing of interest to note apparently."

Things perked up a week later when Confederate General Jubal Early led a force of 12,000 soldiers up the Shenandoah Valley into Maryland to divert Union forces and relieve Grant’s pressure on Richmond. On July 5 Early’s troops crossed the Potomac then advanced to the Monocacy River, where on July 7 they pushed back a smaller force of Federals patched together by General Lew Wallace. By July 11 most of Early’s men reached the fortifications northwest of Washington, which were lightly manned since all available men had been sent to the Virginia front. A sudden attack might allow the rebels to break through and sack the Union capital.

Washington was in a state of near panic, as Hill’s diary recorded. "The city filled with strange rumors of engagement," he wrote on July 10th, "the Rebels are a coming is the Report." There was further worry the next day: "The excitement on the increase. a proclamation hourly looked for calling upon all the citizens to take up arms. Washington appears to be the real point of attack having only made a diversion on Baltimore." Hill described the city’s frantic rush to prepare: "Stores closed. Citizen soldiers in arms. The streets filled with marshall men." Communications had been cut between Washington and Baltimore, and the Confederates were reportedly marching "in full" down the Seventh Street Road from Silver Spring, Maryland toward Fort Stevens just outside the capital.

All able-bodied men, including raw militia recruits, government clerks, and convalescents from Union military hospitals, were mobilized to defend Washington’s perimeter. This motley collection of soldiers was bolstered by the arrival of six boatloads of men under General Horatio Wright that Grant sent from the Army of the Potomac. They arrived just in time. On the 11th Early hesitated and reconnoitered, and the next morning he called off his planned assault when he watched the Union rifle pits and parapets at Fort Stevens fill up with soldiers from Wright’s Sixth Corps, recognizable by the Greek cross badges on their caps. Told that more of Grant’s men were on the way, Early ordered his men to retreat after dark. On July 13th they pulled out and headed for the Potomac River, which they crossed the next day. The federals had let Early’s army escape intact, but Washington’s scare was over.

Hill’s diary reflects the delay in getting the news. On July 13th Early was already retreating but Hill anticipated a fight: "Every thing looks warlike here, but the old 6th Corps is on hand. I feel safe when I look upon the Greek cross their Badge-- The old and valliant men have I not fought beside them[?]" Only the next day did he learn that "skirmishing has ceased and the Army of Breckinridge and Brad Johnson is on the back track again"—a great relief, but also the occasion for a return to the boredom of convalescence.

A milestone in Hill’s recovery occurred on July 17th, when he "walked for the 1st time leaning upon the shoulders of Jack and Carter from the Hospital." Sometimes he pushed himself too hard: "Unwell to night. This in consequence of taking too much exercise," he wrote on July 26th. Yet the next day his diary ends on a decidedly positive note: "Feel rather better this morning."

Hill’s wound resulted in his discharge for disability on November 30, 1864. He returned to the same regiment as Major in January, 1865, but according to Private Wood he was no longer capable of field duty. Hill is not mentioned in accounts of the regiment’s engagements at Dabney’s Mill and Hatcher’s Run in February and March, 1865, respectively, and again at the pivotal battle of Five Forks on April 2nd. On March 13, 1865 Hill was promoted to Brevet Colonel for "gallant and meritorious service" in the action at Magnolia Swamp on his near-fatal day at Cold Harbor. The promotion was regularized on May 8, 1865, and three days later Hill was discharged from the Sixteenth Michigan. He was named an Inspector General of the 1st Division on June 15, 1865 then mustered out the following month.

Library of Congress

Recovery

To his own surprise and his doctor’s as well, Captain Hill did not die of his rifle wound. His journal continues after Cold Harbor and is filled with updates on his condition. At the field hospital, Hill’s friend Jack Wood of the Sixteenth administered "stimulants"—probably whiskey—to dull the pain and arranged for an army wagon to take Hill to White House Landing on the Pamunkey River. Hill suffered excruciating pain on the wagon journey to the wharf at White House, where Wood placed him on a steamer bound for Washington. His prospects improved once he arrived at Armory Square Hospital on the National Mall. There he rested comfortably and Dr. Willard Bliss, the Michigan surgeon in charge, decided not to risk probing his wound but simply to let it heal.

Some of Hill’s nights were "wretched" and fearful, but his improvement was obvious. The diary chronicled his steps toward mobility. "Feel better to day," he wrote on June 20, when Jack (probably still Jack Wood) "wheeled me about the floor a little for the first [time]." The next day he "went out for the first time . . . in the Hospital chair." Hill recognized his progress and was gratified by it: "Expect am safe in saying that I am gaining slowly," he wrote. "Every day is a great desideratum." Within ten days of his hospitalization he was writing and receiving letters.

Hill’s days were brightened by a steady flow of visitors, who bore gifts of berries and brandy as well as towels and eating utensils. Some were apparently old friends, like the Houserights of Washington. Mrs. Houseright was so helpful that Hill was effusive in his praise for her and apologetic after an argument between them. Other callers were military colleagues who were also wounded or on leave. "About 6 Friends call on me and keep my spirits pretty well as I do theirs I don’t know which," Hill wrote after one such visit. From army friends and the newspapers Hill picked up snippets of war news—that Grant’s army had crossed to the south side of the James River, for example, and that the Union navy had finally put the Confederate raider Alabama out of commission. In mid-June a Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin, apparently relatives of Hill, made a surprise four-day visit accompanied by other family members. Especially notable was a visit from "Libby" Custer, the wife of the flamboyant young Union officer from Michigan, George Armstrong Custer.

On July 2 Hill moved to private rooms away from the hospital. He found his new quarters "home like" and wrote after his first day there that he "never passed a happier day in my life." Still, away from the hospital the flow of visitors slowed down and along with it the buzz of gossip and war news. "How commonplace every thing is becoming in my Diary," Hill complained resignedly on July 5th. "Nothing of interest to note apparently."

Things perked up a week later when Confederate General Jubal Early led a force of 12,000 soldiers up the Shenandoah Valley into Maryland to divert Union forces and relieve Grant’s pressure on Richmond. On July 5 Early’s troops crossed the Potomac then advanced to the Monocacy River, where on July 7 they pushed back a smaller force of Federals patched together by General Lew Wallace. By July 11 most of Early’s men reached the fortifications northwest of Washington, which were lightly manned since all available men had been sent to the Virginia front. A sudden attack might allow the rebels to break through and sack the Union capital.

Washington was in a state of near panic, as Hill’s diary recorded. "The city filled with strange rumors of engagement," he wrote on July 10th, "the Rebels are a coming is the Report." There was further worry the next day: "The excitement on the increase. a proclamation hourly looked for calling upon all the citizens to take up arms. Washington appears to be the real point of attack having only made a diversion on Baltimore." Hill described the city’s frantic rush to prepare: "Stores closed. Citizen soldiers in arms. The streets filled with marshall men." Communications had been cut between Washington and Baltimore, and the Confederates were reportedly marching "in full" down the Seventh Street Road from Silver Spring, Maryland toward Fort Stevens just outside the capital.

All able-bodied men, including raw militia recruits, government clerks, and convalescents from Union military hospitals, were mobilized to defend Washington’s perimeter. This motley collection of soldiers was bolstered by the arrival of six boatloads of men under General Horatio Wright that Grant sent from the Army of the Potomac. They arrived just in time. On the 11th Early hesitated and reconnoitered, and the next morning he called off his planned assault when he watched the Union rifle pits and parapets at Fort Stevens fill up with soldiers from Wright’s Sixth Corps, recognizable by the Greek cross badges on their caps. Told that more of Grant’s men were on the way, Early ordered his men to retreat after dark. On July 13th they pulled out and headed for the Potomac River, which they crossed the next day. The federals had let Early’s army escape intact, but Washington’s scare was over.

Hill’s diary reflects the delay in getting the news. On July 13th Early was already retreating but Hill anticipated a fight: "Every thing looks warlike here, but the old 6th Corps is on hand. I feel safe when I look upon the Greek cross their Badge-- The old and valliant men have I not fought beside them[?]" Only the next day did he learn that "skirmishing has ceased and the Army of Breckinridge and Brad Johnson is on the back track again"—a great relief, but also the occasion for a return to the boredom of convalescence.

A milestone in Hill’s recovery occurred on July 17th, when he "walked for the 1st time leaning upon the shoulders of Jack and Carter from the Hospital." Sometimes he pushed himself too hard: "Unwell to night. This in consequence of taking too much exercise," he wrote on July 26th. Yet the next day his diary ends on a decidedly positive note: "Feel rather better this morning."

Hill’s wound resulted in his discharge for disability on November 30, 1864. He returned to the same regiment as Major in January, 1865, but according to Private Wood he was no longer capable of field duty. Hill is not mentioned in accounts of the regiment’s engagements at Dabney’s Mill and Hatcher’s Run in February and March, 1865, respectively, and again at the pivotal battle of Five Forks on April 2nd. On March 13, 1865 Hill was promoted to Brevet Colonel for "gallant and meritorious service" in the action at Magnolia Swamp on his near-fatal day at Cold Harbor. The promotion was regularized on May 8, 1865, and three days later Hill was discharged from the Sixteenth Michigan. He was named an Inspector General of the 1st Division on June 15, 1865 then mustered out the following month.

NPS Photo

After the War

At a reunion of the 16th Michigan in 1893, thirty-five surviving members signed a petition requesting that Hill be granted a Medal of Honor. Commanding the Brigade skirmish line at Cold Harbor, they wrote, Hill had "charged the enemy’s masked batteries … for the purpose of drawing and determining their fire and strength, a . . . hazardous undertaking which was accomplished with great coolness and courage." General Daniel Butterfield submitted the petition to the Secretary of War, and on December 4, 1893, while living in St. Louis, Michigan, Hill received the Medal of Honor "for distinguished gallantry at Cold Harbor, Va., June 1, 1864." The citation reads: "Led the brigade skirmish line in a desperate charge on the enemy's masked batteries to the muzzles of the guns, where he was severely wounded."

Hill suffered from his wound at Cold Harbor for the rest of his life, and his disability worsened as he aged. In his pension records the examining physicians testify that the bullet had lodged in the ileum, the lower part of Hill’s small intestine, and that the injury rendered him partially incontinent and "unable to stand on his feet without support and then with difficulty." In 1890 Hill described his disability as "increasing for the last ten years I have been unable to be without the constant aid and attendance of another person am unable to dress or undress or attend the calls of nature alone. I cannot control my bowels and in consequence am compelled to lead a life of seclusion."

His seclusion was not total, however. In January 1868 Hill married Mara Elizabeth Brigham of Jackson, Michigan, who remained his helpmate until the end. The couple was apparently childless. Although they spent most of the next decades in Michigan, at times they lived in Pennsylvania and New York, and in the 1880s they lived in Newfoundland for several years. For much of the 1890s Hill resided at the Alma Sanitarium near St. Louis, Michigan.

Despite his disability, Hill managed to attend several brigade and regiment reunions, sometimes accompanied by Jack Wood, who again served as his personal attendant. In June 1889, Hill gave a speech to thirty veterans of the 16th Michigan who gathered on Little Round Top to dedicate the regiment’s monument on the southwest face of the hill. In 1892 he commemorated "The Last Charge at Fredericksburg" in an address to the Third Brigade Association which was later published.

He remained involved in commemorating the war during his last year. In 1900 Hill published a "Roll of Honor" of the 16th Michigan, the result of two years’ research; it showed that 251 members of the regiment had died in battle or as a result of battle wounds. In May of that year Hill gave yet another speech during ceremonies for the laying of a cornerstone for a monument to the Fifth Corps at Fredericksburg. That fall he attended a reunion of the 16th Michigan in Flint. Shortly thereafter, on October 23, 1900, Edward Hill died at Green Bay, Wisconsin. The primary cause was an intestinal obstruction, the final complication from his battle wound. He is buried at Fredericksburg National Military Cemetery in Virginia.