Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

Education Congressman, Education President (Part II)

Image courtesy of the University of North Carolina

Congressman Garfield’s interest in education was not confined to the common schools. In 1868 he drafted a bill supporting military instruction in colleges, similar to today’s ROTC. It did not pass. But two years earlier Garfield had added a provision for schools on military posts to the annual budget for the army. That provision remained in the army appropriation each year, without much action until 1878. Then “measures were taken at nearly all the permanent military posts toward the establishment of schools for promoting the intelligence of soldiers and affording education to their children, as well as to those of officers and civilians at the remote frontier posts.”

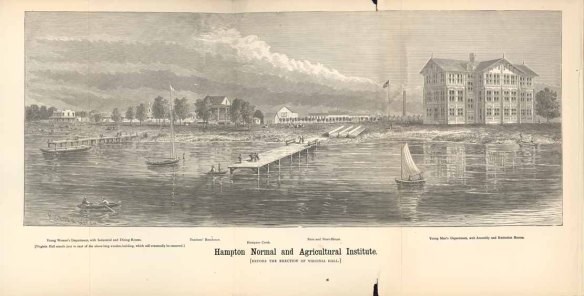

Garfield was ambivalent on the idea of land grant colleges. “I do not believe in a college to educate men for the profession of farming. A liberal education almost always draws men away from farming. But schools of science in general technology are valuable.” As a trustee of Hampton Institute, a new school for the education of freedmen in Norfolk, Virginia, Garfield recognized the need for industrial and agricultural training to promote self-sufficiency in a previously dependent population. He hoped, however, that the curriculum at Hampton would quickly evolve past an emphasis on manual labor and subsistence farming, and strongly encouraged the normal school, which trained teachers. In 1870 he supported an appropriation for the School for the Deaf and Dumb (now Gallaudet College) in the District of Columbia, which, he argued, was essentially a normal school for teachers of the disabled.

Smithsonian Institution

Congressman Garfield was also an enthusiastic supporter of the US Geological Survey and the Naval Observatory.

We don’t know, of course, what kind of education President Garfield might have been, but we do have two hints, the first from his letter of acceptance of the Republican presidential nomination:

“Next in importance to freedom and justice is popular education, without which neither freedom nor justice can be permanently maintained. Its interests are entrusted to the States, and to the voluntary action of the people. Whatever help the nation can justly afford should be generously given to aid the States in supporting common schools.”

He was more eloquent and more inspiring in his Inaugural Address.

“It is the high privilege and sacred duty of those now living to educate their successors, and fit them, by intelligence and virtue for the inheritance which awaits them.”

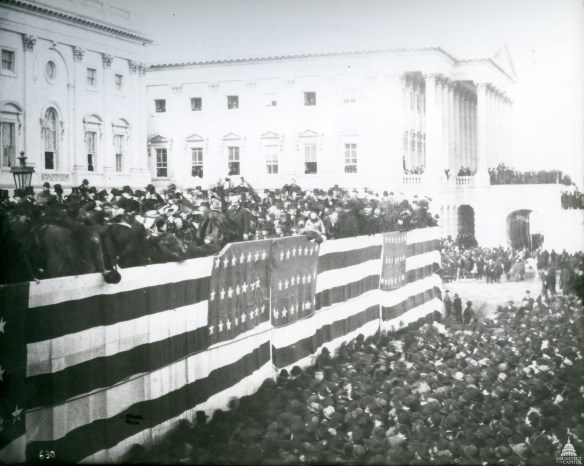

Architect of the Capitol

These statements, while forceful and inspiring, do not explain why Garfield was so committed to the education of every American. For that, we need to look back at a speech before the National Education Association in February, 1879. In concluding his remarks to the nation’s school superintendents, Garfield offered a warning.

“…[British historian Thomas B.] Macaulay said that a government like ours must inevitably lead to anarchy; and I believe there is no answer to his prophecy unless the schoolhouse can give it. If we can fill the minds of all our children who are to be voters with intelligence which will fit them wisely to vote, and fill them with the spirit of liberty, then we will have averted the fatal prophesy. But if, on the other hand, we allow our youth to grow up in ignorance, this Republic will end in disastrous failure. All the encouragement that the National Government can give, everything that States can do, all that good citizens everywhere can do, and most of all what the teacher himself can do, ought to be hailed as the deliverance of our country from the saddest distress.”

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, December 2015 for the Garfield Observer.