Last updated: July 28, 2021

Article

Education Congressman, Education President (Part I)

Hiram College Archives

In his Inaugural Address James Garfield said, “It is the high privilege and sacred duty of those now living to educate their successors, and fit them, by intelligence and virtue for the inheritance which awaits them.”

James Garfield thought about education all his life—as a student, a teacher, a father, and public official. He used his positions of public trust to encourage and promote education for as many people, and in as many ways as he was able.

At age twenty-six, Garfield earned his degree from Williams College and returned to Ohio to teach at Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, where his higher education began. He was soon named Principal. “Chapel lectures” or morning lectures were a well-established part of the school curriculum, and Garfield presented hundreds of them on a variety of topics, including education and teaching, books, methods of study and reading, physical geography, geology, history, the Bible, morals, current topics and life questions. In a letter to a friend, Garfield described the ways he reorganized the school, “We have remodeled the government, published rules, published a new catalogue, and have…250 students (no primary), as orderly as clock-work, and all hard at work.” Garfield was listed in the catalog of Western Reserve Eclectic Institute as “Professor and Principal and Lecturer” from 1856 to 1866.

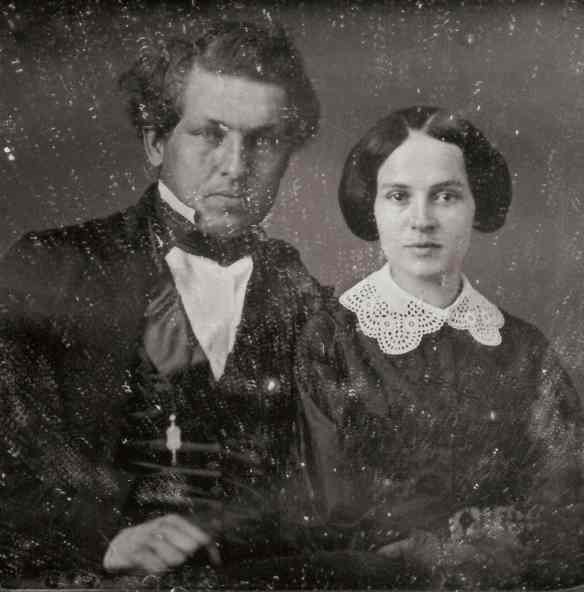

Western Reserve Historical Society

During the years Garfield’s name appeared at the top of the Eclectic’s catalog, he also married Lucretia Rudolph and started a family, served in the Ohio legislature, passed the state bar, and, when the Civil War began in 1861, raised the 42nd Ohio Infantry. He served in the Union army until late 1863, when he took a seat in the U.S. House, representing Ohio’s 19th Congressional District.

Garfield’s goal in leading the Eclectic Institute was to expand its offerings and elevate its standards, laying the foundations for it to become a fully accredited college. That objective was achieved in 1867, when the school was chartered by the state as Hiram College. Speaking to the last group of graduates of the Eclectic, Garfield identified five kinds of knowledge that he believed every student needed, and every college should help them master.

In order of importance, he said that first was “that knowledge necessary for the full development of our bodies and the preservation of our health.” Second was an understanding of the principles of arts and industry (how things work). Third on the list was the knowledge necessary to a full comprehension of one’s rights and duties as a citizen. Fourth was understanding the intellectual, moral, religious and aesthetic nature of man, and his relations to nature and civilization. Finally, a complete education should provide the special and thorough knowledge required for a particular chosen profession. Garfield had obviously thought deeply about what an education ought to be; his list of five kinds of knowledge stands up well to the test of time. The order of importance he assigns, however, deviates significantly from the goals of modern education.

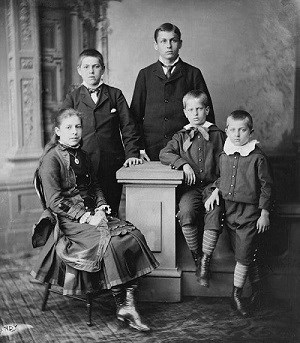

Library of Congress

James Garfield’s papers reveal some of his very specific and firmly held ideas about teaching and learning. Here are a few.

“I, for one, declare that no child of mine shall ever be compelled to study one hour, or to learn even the English alphabet, before he has deposited under his skin at least seven years of muscle and bone.”

“School committees would summarily dismiss the teacher who should have the good sense and courage to spend three days of each week with her pupils in the fields and woods, teaching them the names, peculiarities, and uses of rocks, trees, plants, and flowers, and the beautiful story of the animals, birds, and insects which fill the world with life and beauty. They will applaud her for continuing to perpetrate that undefended and indefensible outrage upon the laws of physical and intellectual life which keeps little children sitting in silence, in a vain attempt to hold its [sic]mind to the words of a printed page, for six hours in a day…This practice kills by the savagery of slow torture.”

“I am well aware of the current notion that…a finished education is supposed to consist mainly of literary culture…This generation is beginning to understand that education should not be forever divorced from industry,–that the highest results can be reached only when science guides the hand of labor…Machinery is the chief implement with which civilization does its work; but the science of mechanics is impossible without mathematics.”

“I insist that it should be made an indispensable condition of graduation in every American college, that the student must understand the history of this continent since its discovery by Europeans; the origin and history of the United States, its constitution of government, the struggles through which it has passed, and the rights and duties of citizens who are to determine its destiny and share its glory.”

U.S. Department of Education

As a member of Congress, Garfield’s most significant achievement was passing a bill that created the first Federal Bureau of Education, a piece of legislation he introduced in April, 1866. It provided for a Commissioner of Education who would be charged with collecting and disseminating information about education in the United States. In arguing for this Bureau Garfield said, “In 1860 there were in the United States 115,224 common schools, 500,000 school officers, 150,241 teachers and 5,477,037 scholars; thus showing that more than six million people of the United States are directly engaged in the work of education. Not only has this large proportion of our population been thus engaged, but the Congress of the United States has given fifty-three million acres of public lands to fourteen States and Territories of the Union for the support of schools.” He made it clear that the purpose of the bureau was to gather information and statistics about schools across the nation, and share it with local and state educators. It should discover the quality and effectiveness of schools for blacks and immigrants as compared to those for native-born whites. The Bureau was not involved in curriculum development or school management.

(Check back soon for Part II!)

written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, December 2015 for the Garfield Observer.