Part of a series of articles titled The Military History of Fort Schuyler.

Article

The Key to the Continent: Early Military History of the Oneida Carry

Courtesy of Arthur Simmons III

For centuries the Haudenosaunee people, including the Oneida Indian Nation, utilized a narrow strip of land situated between the Mohawk River and Wood Creek. Geographically unique, it is here where the waters of the Mohawk flow east to Albany, the Hudson River, and New York City while those of Wood Creek flow west to Oneida Lake, Oswego, and Lake Ontario. The Oneida Carrying Place or De-O-Wain-Sta, was a land portage two to four miles wide, depending on seasonal water levels, that people, largely driven by trade, could carry their canoes between the two waterways with relative ease.One of the earliest written references to the Oneida Carrying Place occurs in September 1724 at a meeting between the Commissioners of Indian Affairs and representatives of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Tuscarora Nations in Albany, NY. It is here that a tribal representative said to the commissioners “you have been at the expense to mend & clear the carrying place & wood creek, and that you will order it further to be mended, for which we return our hearty thanks, for now the old & decrepit may come over the carrying place whereas formerly it was difficult to pass that way but now it will induce & encourage the Far Indians to come to trade here which will engage them to be firmly united to us. It is most certain that Trade is the chiefest motive to promote friendship”.

As Britain and its colonies continued to find themselves in competition with the French for control of the vast North American resources, tensions grew increasingly more hostile between the two super powers of the time.

Starting in 1726 with the establishment of Fort Niagara, along the Niagara River, the French were positioned to control not only access to the Ohio valley, it also exerted their dominance of Lake Ontario. This was primarily achieved by providing a market, at Niagara, for fur traders, saving them the long trip to the British markets in Albany and New York. In response to this aggressive move the British would establish their own trading post at the mouth of the Oswego River on Lake Ontario in 1727. As a result, the Oneida Carrying Place would begin to be utilized by more than just traders, it would also be used by the British military and the merchants hired to supply the garrison at Fort Oswego. From the 1730s through the mid-1750s travel across the carrying place remain largely limited to supplying a small British garrison of 50 men and the seasonal fur trade.

Construction of the storehouses continued for more than two weeks but by June 11, 1755 it was unexpectedly suspended. Alexander would write to the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Sir William Johnson, “On your informing me . . . that it would give offence to the Indians to build any storehouses on the carrying place . . . without their consent . . . I have desired to suspend the building of two storehouses, one on each end of the carrying place.” Alexander then asked Johnson to use his “endeavors” to obtain their consent and allow the construction to continue, which Johnson does at a conference with the Oneidas on July 4, 1755. Johnson would write later that same day to Captain William Williams, who was in command of the troops at the carrying place, that the Oneida Nation had consented but warned him saying “I must earnestly recommend to you that all person who are under your command either soldier or workmen behave with civility & good humor to the Indians. And that no ill usage whatsoever be given them”.

Throughout the summer of 1755, men and supplies crisscrossed the Carrying Place as soldiers and locally hired workmen completed the storehouses and constructed a road between the Mohawk River and Wood Creek which made portaging much easier. To assist in the movement of soldiers and supplies, 20 batteaux were “constantly” employed on the Mohawk bringing supplies up the river and 30 were used on Wood Creek, operating between the Carry and Oswego.

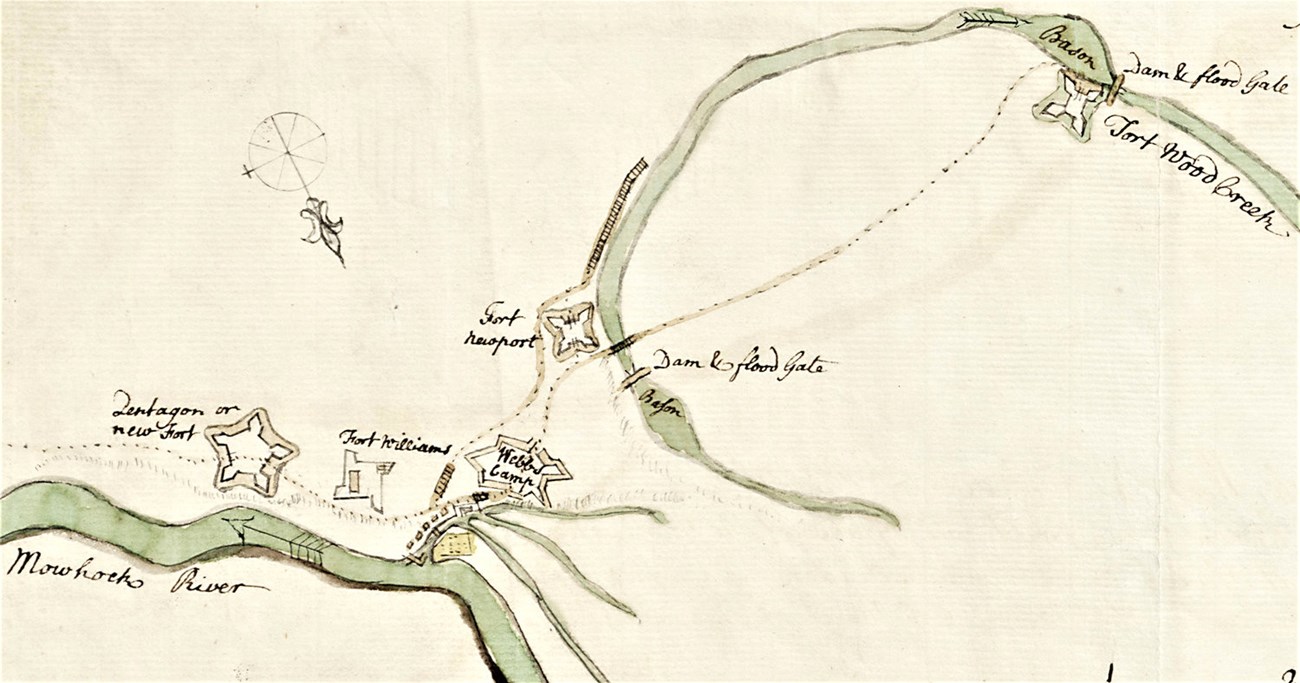

When autumn came to Oswego so did its unpredictable weather. To Shirley and the regimental officers, it become clear that it was much too dangerous to navigate Lake Ontario with their batteaux being that late in the season. He subsequently postponed their attack on Fort Niagara until 1756. As Shirley made his way back to Massachusetts, he began dispersing his army along the way. Leaving approximately 2,000 to winter quarter at Oswego and 180 at the Oneida Carrying Place. His Instructions for Captain William Williams at the Carry was to “employ as many of the men of the detachment under your command as you possibly can, in finishing the Fort this day marked out at this place and called Fort Williams, and completing barracks therein sufficient to contain 150 men. You are also to build therein a storehouse of about the same dimensions of that already built here, and as soon as the barracks are fit to receive the men of your detachment you are to quarter them therein.” Additionally, improvements to the carry road were ordered “you are to employ as many of the men under your command as you judge can be safely spared from Fort Williams in mending and repairing the road from hence to Wood Creek.”

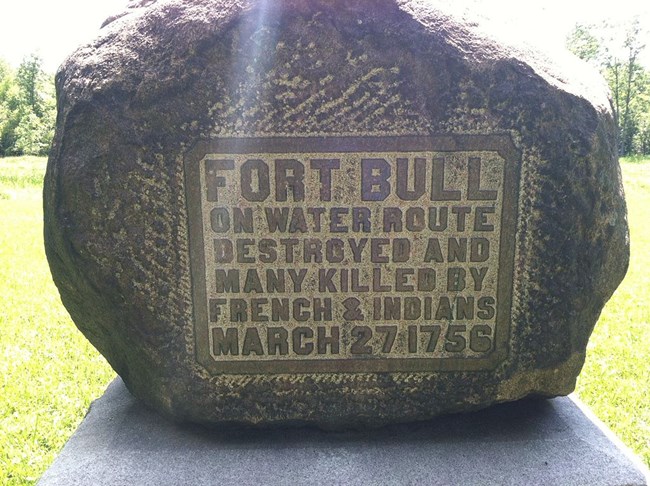

To support this effort, Shirley also ordered an officer and 30 men from Oswego to reinforce Williams’ detachment and have them quartered in Fort Williams. Shirley would also order Captain Marcus Petri and the men under his command to “build a Fort at the upper Landing on the Wood Creek, to be called Wood Creek Fort” and when completed Shirley ordered Williams to “send an officer with thirty men to garrison that Fort.” Additional instructions included the construction of another storehouse and the stockpiling of as may provisions as possible in Wood Creek Fort. This fort would shortly thereafter be named Fort Bull, after Lieutenant William Bull who commanded it.

As the winter of 1755–1756 set in, Wood Creek and Oneida Lake became frozen over, yet the supplies intended for Oswego would continue to be stockpiled at the Oneida Carry. With more than 2,000 troops remaining at Oswego, a desperate situation developed. The men began dying from starvation, exposure, and scurvy. As early as January 1756, pleas were sent from Colonel James Mercer, commander of Oswego to Captain Williams for needed supplies. The situation became so dire that by March 14th Mercer would again write Williams stating, “let me assure you, a few days more will put an end to all we have here.”

Meanwhile the French had learned of the British battle plans when they defeated Major General Braddock and his army at the battle of the Monongahela in the summer of 1755. With knowledge of the Niagara Expedition and the desperate situation at Oswego, on February 13, 1756 Governor Vaudreuil of New France ordered Lieutenant Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry to “command a detachment of troops, Canadians, and savages, numbering 390 to 400 men, to go and take over two houses serving as depots for war munitions, food and belongings.” His destination was the Oneida Carry. After a long march from Fort de La Présentation (present day Ogdensburg, NY) through the North Country wilderness, crossing frozen lakes and forging icy rivers, while enduring the relentless snow and rain, de Léry arrived at his destination. The next day, March 27, 1756 after ambushing a British supply convoy crossing the Oneida Carry and destined for Fort Bull, de Léry had a choice to make. Would he attack Fort Williams located along the Mohawk River, which had cannon and a great number of troops in garrison, or Fort Bull located on Wood Creek, which had no cannon and was brimming with supplies all destined for the starving troops at Oswego? His choice was clear.

De Léry’s raid on the Oneida Carry and the destruction of Fort Bull dealt an utterly devastating blow to the British. With 70 dead and 35 taken prisoner, the loss of life and supplies was significant: 70 barrels of meat, 200 kegs of gunpowder, 30 horses, 16 batteaux, 15 barrels of rum, as well as all the munitions, clothing, and equipment. Of Lieutenant William Bull, de Léry would write in his journal that “he defended himself with all the courage and bravery I have always remarked in English officers. I gave him two chances to say if he wanted to surrender, I made him an honorable offer, but he only strove all the more ardently to defend himself and was killed only when the gate of the fort fell, still trying to defend the entrance.”

Within two months the British would formally declare war on France and begin refortifying the Oneida Carrying Place. Fort Wood Creek (Fort Eagle) would replace the destroyed Fort Bull. Fort Newport would also be erected along Wood Creek (present day Arsenal Street) and Fort Craven or the Pentagon Fort would be built adjacent to Fort Williams (present day East Whitesboro Street) Throughout the summer of 1756, men and supplies continued to cross the Carrying Place destined for Oswego. However, that would all change in August when Captain John Parker, Commander of Fort Eagle/Wood Creek, would inform Major Charles Craven that “Oswego is taken, and all the Officers and Men made Prisoners.” It is at this moment, that Fort Eagle/Wood Creek becomes the western most outpost of the British Empire in New York.

A few days later, reinforcements led by General Daniel Webb would arrive. However, with Oswego now taken by the French, the British became very fearful that the Oneida Carrying Place would be their next target. The commander of the British forces in North America, Lord Loudoun would write Webb the following, “I think your situation a dangerous one, and yet it is absolutely necessary for us, to keep possession of as much of the country as we possibly can, with prudence; if by your Intelligence, you find that the Enemy are coming against you, with a Force you are [in] no way able to resist, tho’ I reckon you 1400 men . . . in that case it will be necessary, to harass the Enemy in their approach as much as possible” the orders go on to say, “and if you are forced to retreat, you will destroy all the Forts” Webb, acting on these orders would burn down all the forts on the Oneida Carry and retreat to German Flatts (Herkimer, NY) by the end of August 1756, marking an end to the British use and occupation of the Carry for two years.

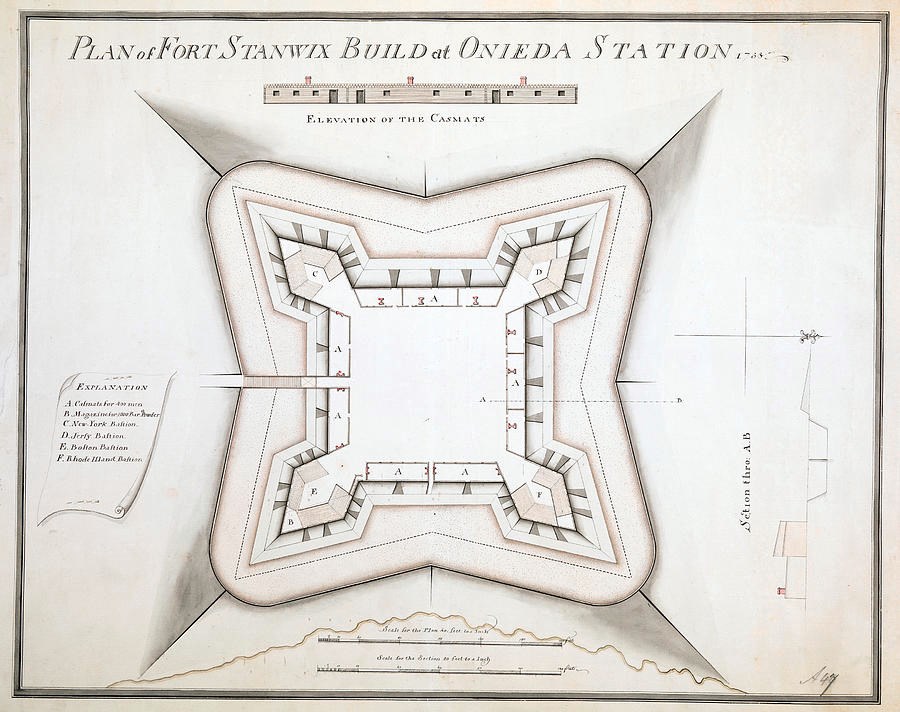

The construction of Fort Stanwix would begin in the summer of 1758, after Sir William Johnson again obtained permission from the Oneida Nation, promising them that the fort would be demolished at the end of the war and that trade would be plentiful. For the British it was imperative to reestablish themselves on the Oneida Carry. While General John Stanwix focused on the fort’s construction, Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet led a force of over 3,000 men to attack the French at Fort Frontenac (present day Kingston, Ontario). This successful action would disrupt the French supplies destined for their western forts and result in the release of British soldiers taken prisoner at Oswego in 1756.

In 1759 the construction of Fort Stanwix continued and many improvements were made to the Oneida Carry including clearing the woods 500 yards around the Fort, installing a flood gate at Bull’s Fort (Fort Wood Creek) in order to assist batteaux in their navigation, and the construction of a post at Canada Creek. This post would be called Fort Rickey. Also, that year General Jeffrey Amherst would order General John Prideaux and Sir William Johnson to reestablish a fort at Oswego, and attack Fort Niagara. Both efforts were successful and in 1760, Amherst himself with an army of 10,000 would cross the Oneida Carry on his way to capture Montreal.

Three years later, the 1763 Treaty of Paris would be signed ending the Seven Years War. Yet the Oneida Carrying Place would continue to shape history. From its humble beginning as a wilderness footpath to a City now celebrating 150 years of incorporation, the story of the Oneida Carrying Place, the De-O-Wain-Sta, is uniquely ours.

Last updated: June 4, 2023