Last updated: July 18, 2025

Contact Us

Article

Dwight Smith Interview

Dwight Smith

When not in school with the Navy or travelling across the United States for the Navy, Radar Operator Dwight Smith spent his World War II career on the USS South Dakota, SS Thomas W. Hyde, and the landing ship tank, LST-835. He was in high school when the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred and drafted into the Navy in 1943. After basic training, Smith became part of the Fire Control Division, which worked to make the gunfire accurate, considering the type of gun, the wind velocity, etc. He was stationed in the South Pacific, San Francisco, and Portland.

He split his college time, attending Green Mountain Junior College and Dartmouth College both before and after the war. His wife didn’t want him to return to sea, so Smith worked in the railroad business for close to five decades.

-

Dwight Smith Interview Part 1

Dwight Smith served in the Navy during World War II. He was never stationed in the Aleutian Islands, but he recounts many interesting stories from his time onboard the USS South Dakota, SS Thomas W. Hyde, and LST-835. After the war he had a family and a long career with railroads. This is part 1 of his interview.

- Credit / Author:

- NPS/Joshua Bell

Interview with Radar Operator 3/c Dwight SmithAleutian World War II National Historic Area Oral History Program

June 22 & 27, 2016 Intervale, New Hampshire

Interviewed by Joshua Bell, Park Ranger, National Park Service

This interview is part of the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area Oral History Project. This interview was recorded with the interviewee’s permission on a digital recorder. Copies of the audio file are preserved in mp3, wav and wma formats and are on file at the offices of the National Park Service in Anchorage, Alaska.

The transcript has been lightly edited.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

June 22, 2016

[Start of recorded material 00:00:00]

Joshua Bell: Today is June 22, 2016. I’m Josh Bell, a park ranger with the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area. Could I have you say your name for the record, sir?

Dwight Smith: Dwight A. Smith.

Joshua Bell: All right Mr. Smith. And it’s okay that record this conversation today?

Dwight Smith: It is.

Joshua Bell: Excellent. When and where were you born, sir?

Dwight Smith: Baltimore, Maryland, January 16, 1925.

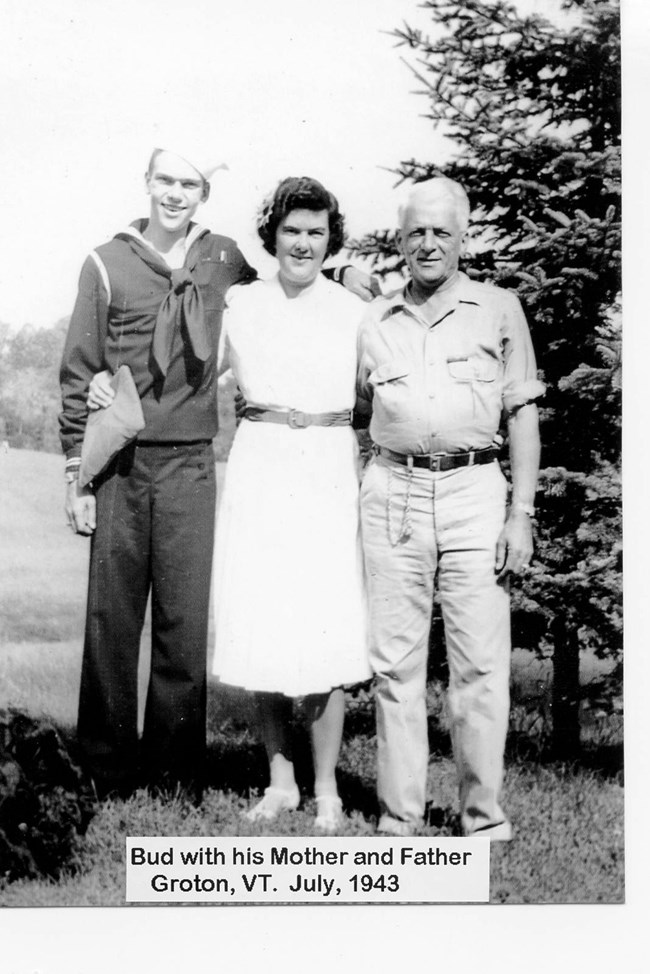

Joshua Bell: And what were your parents’ names?

Dwight Smith: [00:00:35] Captain Dwight Smith, and Beatrice Wilson Smith.

Joshua Bell: And what did they do?

Dwight Smith: My father was a merchant seaman, captain of ships, and my mother was a housekeeper, I mean, a stay-at-home mom.

Joshua Bell: A stay-at-home mom.

Dwight Smith: Yeah.

Joshua Bell: Did you have any siblings?

Dwight Smith: Yes, one sister.

Joshua Bell: One sister. And you grew up there in Maryland?

Dwight Smith: No. At the age of three, my father’s home port was changed from Baltimore, Maryland to Brooklyn, New York. So, from my age four right through sophomore year of high school, I lived in Brooklyn, New York.

Joshua Bell: What was it like growing up in the ‘20s and ‘30s?

Dwight Smith: Well, I survived it okay. On the question, my father never missed a trip on this…with his ship, and we were comfortable during the Depression.

Joshua Bell: What was it like having him gone so often?

Dwight Smith: Not good at all. I really didn’t have a father. He’d be gone for two months at a time, home for a week, and off again. Never at home for Christmas, or birthdays, or any of those things.

Joshua Bell: Oh, Jeez. How did your mom manage?

Dwight Smith: First of all, her mother lived with her. My grandmother lived with her until my grandmother passed away when I was 11. And she was a big help to help bringing up the kids and keeping my mother on an even keel. It wasn’t easy.

Joshua Bell: Oh, go ahead.

Dwight Smith: Let me tell you an incident. When I was discharged from the Navy, I said to my lady friend, “I may go back to sea.” And she said, “The sea or me.” And we were later married, and stayed married for 62 years.

Joshua Bell: That’s fantastic.

Dwight Smith: Yeah.

Joshua Bell: So, as a kid, how did you like living in New York?

Dwight Smith: Let me say that I liked it better, because every summer we went to our small house we had in the little village of Groton, Vermont. G-R-O-T-O-N, Vermont. So that was our summer home, and as soon as school let out in Brooklyn, we loaded up the car and headed north, and I spent the summer in Vermont, and then returned to Brooklyn around Labor Day.

Joshua Bell: And where did you go to school?

Dwight Smith: Public school in Brooklyn, New York. P.S. 97, Seth Low Junior High School, New Utreckth and Lafayette High School. And then, for my junior and senior year, I went to an out-of-state boarding school, Mount Hermon School in Mount Hermon, Massachusetts.

Joshua Bell: What’s the highest grade you completed?

Dwight Smith: I’m a college graduate.

Joshua Bell: Where’d you go to college?

Dwight Smith: Wait a minute. Two years to Green Mountain Junior College in Vermont, and two years… Well, anyway, two years in Dartmouth College. I got my diploma from Dartmouth College in February of 1947.

Joshua Bell: Excellent. So, when were you in college, what years?

Dwight Smith: I graduated from Mount Hermon in June of 1941. And I graduated from Green Mountain College in May of 1943. And my first two semesters at Dartmouth College were through the Navy V-12 College Training Program. And my final two semesters at Dartmouth College were after the war, so it was 1946-47.

Joshua Bell: The V-12 Program; is that the Navy equivalent to the Army Specialized Training Program?

Dwight Smith: Well, it’s the equivalent of B5 in the Air Force. V-12 in the College Training Program, and when you finished your college work, you ordinarily went on to a 90-day wonder school or midshipman school, and I did that. I mean, I went to the 90-day wonder school, but I came down with the German measles after 30 days, and I was hospitalized for a few days, and by the time I returned to the midshipman’s school, it was decided that… I was so far behind, losing a few days, that they decided I ought to go back into the regular part of the Navy as a seaman first class.

Joshua Bell: Sure. When you were in high school, do you remember hearing about what was going on in Europe and in Asia?

Dwight Smith: Well, I was in high school when December 7, 1941.

Joshua Bell: And what was the general reaction to that?

Dwight Smith: The whole nation went to war. I mean, the whole nation. It was everybody was immersed in World War II in some way, you know. My parents, my father was sailing still between West Africa and New York. And my mother, you know, had rations; butter, and meat, and whatever. Your tires; you couldn’t buy new tires for your cars. And, in fact, you couldn’t buy a new car. We all survived it. We all got behind the war effort, everyone.

Joshua Bell: What do you remember thinking about the attack at Pearl Harbor?

Dwight Smith: Oh, I remember thinking it was a terrible thing, and I went right back to… Let’s see, I was just 16, so I went back to Green Mount College, and after two years of… This is the junior college, two-year college, and as the time went by, more and more of our male students were either called up to service, or volunteered to go into the service. By the time I graduated in May of 1943, I was one of only four or five males left in the student body.

Joshua Bell: What was that experience like?

Dwight Smith: Well, it was pretty sad, seeing the guys going off to war. And, yes, it was, kind of, sad.

Joshua Bell: Did the professors have any reaction to that?

Dwight Smith: Yeah, some of them were drafted.

Joshua Bell: Some of them were drafted.

Dwight Smith: Yeah, because they were young enough to be drafted.

Joshua Bell: What was your course of study?

Dwight Smith: I majored in… what does my diploma say… Business Administration.

Joshua Bell: Business Admin. Okay.

Dwight Smith: Yeah. And, when I graduated, I was one of the few of the males left to graduate. In the following year, the school went 100% female. I was the final male student until a number of years later, they went back to both males and females.

Joshua Bell: You must have…

Dwight Smith: They’ve gone to…

Joshua Bell: Oh, go ahead.

Dwight Smith: They’ve gone to a four-year school, now, Green Mountain College has. When I went, it was a junior college –– two years.

Joshua Bell: So, your dad was going back and forth to Africa at this time?

Dwight Smith: Yes, his… He worked for a steamship company called the American West African Line, and his home port was pier 36 in Brooklyn, New York, Atlantic Basin. And, he sailed from there to the… Starting at the Azores and the Canary Islands, working down the coast of West Africa to the Belgian Congo, at that time, the Belgian Congo. And it was, you know, general cargo, and off-loading, and sometimes they have piers to tie up to and unload, but other times, he had to anchor well off shore, and they would come out in wooden carved canoes and pick up the cargo and row ashore with it. It was quite primitive, the ports he called on.

Joshua Bell: There must… Was there any concern about German U-boats attacking?

Dwight Smith: Let me tell you. In October of 1942, a German U-boat sank my father’s ship.

Joshua Bell: Oh, dear.

Dwight Smith: Oh, dear, yes. He survived the sinking, and he was the last one off the ship, and he got into a life boat, the capacity, written capacity of 24 people, but 34 men and one woman in his life boat.

Joshua Bell: How long were they at sea?

Dwight Smith: Ten days. They were not picked up. He navigated to Barbados Island.

Joshua Bell: Wow.

Dwight Smith: It took ten days to get there. He carried a sextant and a compass in a waterproof bag, with the chain around his neck, when he went over. And that enabled him, along with his knowledge of seafaring, he was able to navigate that life boat to Barbados Island. They were never picked up. He just hit the island. Wow.

Joshua Bell: I can’t imagine you and your mother’s reaction to that, once you found out.

Dwight Smith: Well, that was another big problem. This was October of 1942.

Joshua Bell: Right.

Dwight Smith: My mother and I didn’t know if he was dead or alive. And he wasn’t able to tell my mother that he was alive until December of ’42.

Joshua Bell: Wow.

Dwight Smith: I mean, he was on this British-held island, but… They just answered everything. You couldn’t send a message to home. Terrible. My mother did not know if he was dead or alive.

Joshua Bell: But she knew the ship had gone down.

Dwight Smith: Oh, yeah. No. I’m not sure she knew that it went down. Yes. Because another… Somebody else got ashore sooner and told my mother that the ship went down. He didn’t know what happened to the Captain. Pretty sad. Now, again… Then I was out in the South Pacific in ’43; this was ’42, and my mother went through hell between her husband and her only son.

Joshua Bell: So, what led you to choose the Navy?

Dwight Smith: I was drafted. At Draft Board #1 in St. Johnsbury, Vermont said, “We have a choice today; you can choose the Navy, Marine Corp., Army, or Coast Guard.” And being as my father was a sea captain, I raised my hand for the Navy.

Joshua Bell: So, it runs in the family.

Dwight Smith: I guess so. No. My father ran away from home. He was a minister’s son. He ran away from home at the age of 16, and went to sea. What a story. And he was in the Navy in World War I as a lieutenant.

Joshua Bell: He was?

Dwight Smith: After sailing… He graduated from nautical school in 1907, New York Maritime Academy. And he was a graduate out of nautical school. His first berth was on a lighthouse-keeping ship on the East Coast, was headed for the Philippines, because we had just stole the Philippines from the Spanish, and so it was now our…our necessity to take care of sea in the Philippines Islands, so… It’s, like, the light ship keeping ship was shipped out to the Philippines, and by way of Cape… What’s the… Cape… Cape of South America.

Joshua Bell: Oh, yes.

Dwight Smith: The Panama Canal had not been built, and he was a junior officer on that ship. And once they reached Manilla, he stayed in the middle of the Philippines until World War II. I mean, World War I. He sailed on British-owned ships out of Manilla up to Indo-China, Japan, China. You name it, in the Pacific. [Unintelligible 00:13:37] islands. He worked his way up to finally becoming a first officer, and then later a captain. And then, when the British went into war in World War I, these ships that he was sailing on out of Manilla, were part of the British Admiralty, see. You know, they took over these cargo ships as British Navy.

And, when the United States heard about him being out in the Philippines and working for the British, they brought him home to the United States and made him a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy. And they stationed him at a desk job in Wales, which is the last thing he wanted. When he got out of World War I, he went back to sea as a merchant skipper, merchant ships, cargo ships. And he sailed around the world [unintelligible 00:14:38] of Europe and back and [unintelligible 00:14:40], and then he finally landed this job with the American West African Line around 1928, I think. He was torpedoed in 1942, and then he got a shore job.

Joshua Bell: Then he was home?

Dwight Smith: Yes. Yes, but he moved from Brooklyn, New York to New Orleans, Louisiana, because of his shore job. He was a surveyor for the insurance underwriters who… He inspected cargoes of ships before they sailed out of the United States, to make sure they were properly stowed, or not overweight, or whatever else. He’d give them assurance, the underwriters wanted to know about. So he was an official inspector, and he’d go aboard these ships and inspect the cargoes. And he really enjoyed it, because he got to meet a lot of old friends… Of course, you know, with fellow sea captains.

Joshua Bell: I’m sure your mother was pleased with this development.

Dwight Smith: Oh, yes indeed. I will say, though, that when he was transferred to New Orleans, my mother didn’t like summer in New Orleans, so she went back to Vermont to spend the summer in our home in Groton, Vermont. And then he’d come up when he had a vacation.

Joshua Bell: Were you able to ? When did he get home after being torpedoed?

Dwight Smith: December of 1942.

Joshua Bell: It was December of ’42? And I’m sure there must have been a welcome home party?

Dwight Smith: I forget the details. I do remember he came home alive. What my mother went through in World War II, with my father out there in the Atlantic, and me in the South Pacific in the following year, 1943. It wasn’t easy for her.

Joshua Bell: Oh, not at all.

Dwight Smith: That’s when my lady friend said, “The sea or me.” Because she knew what my mother went through.

Joshua Bell: Oh, yes.

Dwight Smith: So, I went into the railroad business two days after she said, “The sea or me.”

Joshua Bell: You said you signed up in St. Johnsbury, Vermont.

Dwight Smith: Yeah. I was drafted then, and the Draft Board #1 in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, because that’s the county seat for our summer home in Groton, Vermont.

Joshua Bell: For Caledonia County.

Dwight Smith: Yes. I got my driver’s license and things when I was already in the Navy.

Joshua Bell: Yeah. What was that day like?

Dwight Smith: What about that?

Joshua Bell: What was that day like? The draft board?

Dwight Smith: Kind of scary. I didn’t know what I was going to be, but when they said I had an option to the four branches of the service, I said, quickly, I said, “Navy.” I wanted no part of… I wanted to have a roof over my head and three square meals a day. And you get that on a ship, and you don’t get that when you’re in the Army.

Joshua Bell: That’s right. How did your dad and mom react to you getting drafted?

Dwight Smith: Well, they just accepted it, because we were at war. I came home from boot camp, ten days leave. I went up to Groton, Vermont. My parents were up there, and my grandfather was still alive. He lived up there, my father’s father. And, I came home in my full uniform, and I went to see them, and they were quite pleased with that. Once I got back to report back after my leave from boot camp, I thought, you know, they’re going to send me to a technical school of some kind, or some kind of a… No. They sent me right down Norfolk, Virginia, and said, “Get aboard this U.S.S. South Dakota battleship –– We need you.” Right out of boot camp. Wow.

Joshua Bell: How did you feel about that?

Dwight Smith: Scared to death. They put me on this ship in Norfolk, Virginia, and it was in dry-dock. It had just come down from the North Atlantic. It was working with the British fleet, protecting the freighters headed for Murmansk. Murmansk, Russia, which is above the… It’s way, way, way up north.

Joshua Bell: Yeah.

Dwight Smith: One tip of Norway and around into Murmansk. And the battleship South Dakota worked with the British fleet, protecting loose convoys, and also trying to entice German battleships, which were in the fjords in Norway, to come out and get shot. They stayed put. They did not come out.

Joshua Bell: How many ships would go in your convoy?

Dwight Smith: I have no idea. See, this was… I was in the Navy when the South Dakota was heading up.

Joshua Bell: Oh, that’s right. That’s right. I wanted to ask –– What was basic training like?

Dwight Smith: Boot camp? Oh, like Hell. I never knew how to fold sheets or make a bed, or I didn’t like to get up at 6:00 o’clock in the morning. I did not like boot camp.

Joshua Bell: What do you remember about your superior officers?

Dwight Smith: Well, they were usually not commissioned officers. They were chiefs, chief’s petty officers that were, you know, leading us, and they were very strict and very rough on us. I guess I was a mama’s boy, and there I was at the age of… How old was I? Eighteen. I had just turned 18, and I didn’t like boot camp. No.

Joshua Bell: Did you make any friends while you were there?

Dwight Smith: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. Yep. But I’ve lost some over the years.

Joshua Bell: Did any of them go with you to the South Dakota? Dwight Smith: Yeah. Two or three of them.

Joshua Bell: Two or three of them?

Dwight Smith: Two or three, actually. Yeah. And we were all lined up on the fantail in the dry-dock, on the ship, being assigned to our divisions. Now, that’s news to me, I didn’t know what divisions were, but they were where they put you to work on the ship. Well, they started calling off your names, and telling you you’re going to division twelve or division six, or you’re going to peel potatoes, or you’re going to be swabbing decks, or chipping paint. Things like that. And then manning a fleet, forty gauged anti-aircraft guns or throwing bags of powder into the 16-inch guns, and things like that. I didn’t really want to do things like that. So, one of the officers made an announcement. He said, “Anybody here have high school math? Raise your hand.” The guys next to me, “Don’t volunteer. Never, never volunteer.” I raised my hand. I got put in the Fire Control Division. Gunfire. Tried to get the bullets to be where that airplane is, at the same time.

Joshua Bell: Oh.

Dwight Smith: And wind velocity, and every little detail had to be cranked into this system to be accurate when you’re firing these 5-inch, twin 5-inch guns, the ones I was working with. And I was put down into the plotting room, which is in the bowels of the ship. And I had earphones on my head, and a hand crank on a computer down in the bowels of the ship. I’d been getting messages from the people who were working the optics parts of Fire Control Division, you know, the trainers, and whatever, using optics back topside, and following this information tube down to us guys in the bowels, because we had a computer in that portion of the ship. It was all vacuum tubes, hotter than Hell. But, the plotting room and the sick bay were the only two parts of the ship that were air conditioned. And then, when things were quiet, we were allowed to sleep on the floor in the plotting room at night, if you desired, when we’re out of danger.

Joshua Bell: And how did you like that job?

Dwight Smith: That job was okay, because I was… At sixteen inches of armor plate on both sides of me, you know.

Joshua Bell: Yeah.

Dwight Smith: And, those guys topside with those 48-millimeter anti-aircraft guns, were totally exposed. I could hear the things going on, and I could feel them, but I never saw them. My watch station, I saw everything, because I was just sitting up on top of a twin 5-inch mount, the director, where the optics were. And my job was to sit there and read my manuals so I’d become a better fire control-man, eight hours a day.

Joshua Bell: Not a bad gig. Dwight Smith: Yeah, I wish I’d had my camera with me, because sitting up there, and I’m watching… We’re in a task force, Task Force 58, and there’s ships as far as the eye can see. And our primary duty on the South Dakota was to protect those carriers. When the planes start flying over, shoot those planes down. That was our main duty. And our secondary duty was to shore bombard Japanese held islands before the Marines and the Army went ashore. Soften them up with our 16-inch guns. I don’t know how much damage we did, but we sure tried. I guess by the time I got out there in 1943, the Japanese Navy had been pretty well annihilated. There wasn’t much left. So we’re, basically, shore bombardments and anti-aircraft on my ship. We’re also within a sea of cruisers, and destroyers, and aircraft carriers as far as the eye can see. It was amazing. And then every so often, we would pull into an atoll somewhere, and, you know, restore our groceries and put the sick guys, and the guys who were injured onto the hospital ship, and things like that. And we would be able to go ashore, on the beach in these islands, under the palm trees. I must say that the women in those little islands got whiter every time we went ashore. And I didn’t drink beer at that point in my life, and… I do now, but I didn’t then. And, when we went ashore, they gave us a chit for two beers, and I got my chit for the two beers, and once I got ashore, I would auction them off. I did very well. There’s a light side to all this story, you know. There’s a light side to it.

Joshua Bell: Absolutely. So…

Dwight Smith: You’ve got to be… You’ve got to make it light because, otherwise, you’re going to go nuts.

Joshua Bell: Did the South Dakota ever come under fire?

Dwight Smith: Yes, but before I was on it, and after I was on it. We were under fire, in that, Kamikaze airplanes tried to sink us. But there was no physical intercourse with other ships, but we were always fighting off these Japanese airplanes. They’d try to drop bombs down our stack, and things like that. Kind of nerve-wracking.

Joshua Bell: That must have been especially nerve-wracking because you couldn’t see what was going on.

Dwight Smith: You know what was especially nerve-wracking, too? My mother. I mean, think about it. She’s already put up with the German U-boat situation, and there I was out there, her little boy.

Joshua Bell: Did you stay in contact with your mom, and your parent…well, your parents?

Dwight Smith: Yes. We’d write emails, they called them, I think, or something like that. Victory mails…

Joshua Bell: Oh, yeah. The V-mails. Yeah.

Dwight Smith: V-mails. Yeah. Oh, yes, we kept in touch. But I couldn’t tell them much about what was happening on the…

Joshua Bell: Oh, right.

Dwight Smith: …They censored our letters before they were mailed. It was pretty sad.

Joshua Bell: So, when you signed up for the Navy, how did you…? Where did you hope to go? Or did you have any aspirations?

Dwight Smith: I’d like to have been assigned to a tug boat in New York harbor. Let me tell you, though… Oh. I’m on the South Dakota. I got on there in about July of ’43, I believe, in Norfolk. And, eight or nine months later, I’m walking through the ship, and there’s this little notice on the bulletin board. “The U.S. South Dakota. You have been given a quota of five of your 2,500 passengers, you can send five of them back to the Navy V-12 College Training Program.” Five of that crew, 2,500 men. Again, “Don’t volunteer.” I said, “Yes. I’m going to volunteer.” I raised my hand, and I got a physical exam, and a conversation with an officer, and a written exam.

But I failed the physical exam to go back to the Navy V-12 College Training Program. It was down in sick bay, and this young doctor was going through, and he said, “Uh oh, your blood pressure is too low.” And he could see that I was a bit broken up about that. But he said, “I tell you what, son. Go up topside, get out a pack of cigarettes, and start smoking one cigarette after the other, and run up and down the deck, and come back down at 2:00 pm,” which I did, and he said, “You passed. Your blood pressure has increased enough that you can go back.”

Joshua Bell: Did it work?

Dwight Smith: Did it work? Yes. I was assigned to the Navy V-12 College Training Program, and I went back home as a passenger on an aircraft carrier that was headed to Pearl Harbor. There was something, probably some repairs to make, or something. So, I was a passenger on the U.S.S. Princeton, a big aircraft carrier, and I was a passenger on it. And then, when we got to Pearl Harbor, they had me in a tent on some hillside in Hawaii. And I said, “Well, when am I going to know when I’m going to get from Pearl Harbor back to the States?” They said, “We’ll let you know when we have a vacancy on a ship going back.” And I said, “Well, how will I know when?” They said, “See that pole outside your tent? There’s a loud speaker on it. When we call your name, you better be ready.”

So, thus, I never did become a tourist in the Hawaiian Islands, because I sat right by that pole for two or three days. And they sent me back. And I filled out an application for the Navy V-12 College Training Program. And there was three colleges I could apply to. Northwestern in Chicago, Columbia in New York City, and Dartmouth College in rural New Hampshire.

Now I’m thinking, first of all, that most of these guys will want to go to New York or Chicago, not rural New Hampshire. So I applied for Dartmouth College, knowing I have a better chance. Not only that, but Dartmouth College was forty miles from our summer home in Groton, Vermont, 40 miles.

Joshua Bell: Right.

Dwight Smith: Well… Okay. They sent me my orders to go home for 10 days leave. So, I get on a train in Oakland, California, spend five days sitting up at a day coach to Woodsville, New Hampshire, and I finally got home to Groton, Vermont. My orders were –– “After your 10-day leave up there, we want you to come back to San Diego, California for further orders.”

Joshua Bell: Oh, Jeez.

Dwight Smith: Yes. Oh, Jeez. So back I go on a train and another route to San Diego, five days sitting on the day coach. I’m at this base in San Diego for three or four days. They hand me my orders to go to Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, 40 miles from where I was! I tell you, you’re looking back, you wonder how we won the war.

Joshua Bell: So much for logistics.

Dwight Smith: Oh, my God, yes. So, I crossed the country three times, by rail, in 30 days.

Joshua Bell: Well, hey, that must have been an experience.

Dwight Smith: Well, yes, but bear in mind that in my two years and eleven months in the Navy, I crossed the country 10 times.

Joshua Bell: Ten times?

Dwight Smith: Ten times, coast to coast. Whenever I was on the East Coast, they wanted me on the West Coast. Whenever I was on the West Coast, they wanted me on the East Coast, and I… Ten times. And once I… Not really crossed coast to coast, but I got from Norfolk, Virginia to Oakland, California by way of Panama Canal and the South Pacific. That’s my first coast to coast trip, was from Norfolk to Oakland, California. It took nine months to do the trip, but that’s what the first one was.

Joshua Bell: I was going to say, you went the long way around.

Dwight Smith: Oh, yeah. And then this thing going down to San Diego and back. Also, though, I also… I crossed the country ten times, coast to coast, seven times by rail, once by the ship, South Dakota, and twice by thumb, hitchhiking.

Joshua Bell: Twice by thumb?

Dwight Smith: Yes. Twice.

Joshua Bell: During your time in the Navy?

Dwight Smith: Yes. Though, the last time was, I’d been discharged out in Bremerton, Washington, and I’m heading home, and I wanted to visit some friends along the way, so I hitchhiked. The first time was during the Christmas/New Years of ’45-’46 when everybody was on the West Coast trying to get to the East Coast, because the war in Japan was over. Oh, I tried, with a buddy, to see if we could get a bus, or train, or airplane, or something to go to the East Coast. We both wanted to get back to New York, as my lady friend was in New Jersey, and his friend was out there somewhere also. So, the two of gave up and we thumbed our way across, and in five days, we made it. Night and day, we got rides.

Joshua Bell: Wow.

Dwight Smith: And, I tell you, it was very interesting. Because when you were doing this, this hitchhiking, protocol was for the military people to line up along the highway, and the fellas first in line would get the first ride. And those guys who lined up way at the end of the line, they may sit there for six or eight hours before they get a ride. So, my friend and I, we overnighted at a bunk in the basement of the fire station of Winnemucca, Nevada. Got up in the morning, bright and early, and boy, what [a line up 00:35:20]. This was in November or December of ’45. The war with Japan was just over. And, we were standing there, just moping, because, “Jeez. We’re never going to get a ride.” Well, we’re really out in the desert. And we saw this cloud of dust. It was a car coming across a little dirt road in the desert, there. Guess where the car ended up? At the highway, right where we were standing. Never mind what protocol is, we jumped in that car and headed east.

An old Indian was driving it, and every roadhouse we passed where he could get a drink, we, the two, my friend and I were sent into the roadhouse to buy him a bottle of beer, because he couldn’t buy it. The Indians were not allowed to drink alcohol. So, we kept feeding him the beers. I think we went 300 miles with him. Anyway, that’s how we got across country in five days. I’d say, you got to get a few breaks. Because I was…

Now I had met this young lady, and she’s in New Jersey, and I’m in California, and I spent Christmas and New Year’s with her. Not New Year’s eve because I was headed back to the West Coast again, because that’s where I was supposed to be. I was sitting on the day coach again. I remember New Year’s Eve, we were crossing through Wyoming, and my mother put a little jigger of whiskey in my suitcase. And I got it out and celebrated the New Year away. Drank sitting on the day coach.

Joshua Bell: Good ol’ mom looking out for you.

Dwight Smith: Yep, in the wilds of Wyoming. So I have many a tale to tell, but I think I ought to condense this, because I started out on the South Dakota, I went through Navy V-12 College Training Program. I graduated from that. I took two semesters at Dartmouth, and, by the way, I was the… Our company… In the Navy, there were companies, and in these college programs, we all wore uniforms, and we all marched up and down the college green, and so forth and so on. Most, or 99.9% of the students, the V-12 students, were either right out of high school or were attending college. And I was the only one in that whole company that had battle stars on my ribbon on my uniform. And, it was quite unique. I get this picture of the whole company marching across the green, and there’s one guy holding something up, and I’m holding the flag in front of the team, because I’m a veteran already.

Joshua Bell: How did the other guys feel about that?

Dwight Smith: The other guys were amazed. They were, you know, awestruck. “How do you do this? How did you get into this college program?” I said, “I raised my hand and volunteered.”

Joshua Bell: And you didn’t have to give up any of your rank to get in, did you?

Dwight Smith: I was still seaman first class.

Joshua Bell: Still seaman first class?

Dwight Smith: Yeah, big deal.

Joshua Bell: How many battle stars?

Dwight Smith: Four.

Joshua Bell: Four battle stars.

Dwight Smith: And my Pacific ribbon, yeah. I had the Atlantic ribbon because I’m getting ahead of myself, here, but I had the Atlantic ribbon. I have five ribbons in all. And I would have had six ribbons if I got the Good Conduct Medal. But I had to be in the Navy for three years to get the Good Conduct ribbon, and I was in the Navy two years and eleven months. Joshua Bell: Oh, Jeez.

Dwight Smith: So, by one month, I never got this Good Conduct ribbon. So, it was the South Dakota, then it was Dartmouth College. And then it was midshipman’s school in the Bronx, somewhere in the Bronx. New York Nautical Academy for my 90-day wonder school. It was going to make an ensign out of me, God willing. And, 30 days into the program –– and it’s an intense program. You’re up and about, and running here, there, and everywhere, and taking exams, and all of it was intense. And after 30 days of it, I came down with the German measles. I was sent over to the St. Alban’s, New York Naval Hospital. And I was there maybe four or five days. And, if you lose four or five days out of the 90-day wonder school, you’re lost. You’re never going to catch up. So, when I went back to Port Schuyler, my name was on the bulletin board that I’m dismissed from this program, along with several others. And, there I was, back into being a seaman first class, and sent to Great Lakes Training Center out of Chicago, for further orders. I was on the East Coast, of course, they had to send me out to Chicago for further orders, they can’t get me any in the east. So, here I am. Now, I have to backtrack on this story, because…

Joshua Bell: Of course.

Dwight Smith: …when I was on the South Dakota, and then I was moved to the States, as a passenger. I was a passenger on the U.S.S. Princeton, which is an aircraft carrier. And while I was on the Princeton, I was carrying my hammock and my mattress, and everything else, over my shoulder. You know, carrying this heavy thing over my shoulder, my bedding. I said to myself –– Jeez, if I go to college, I’m going to have bunk. I’m not going to need this stuff. So I stuffed it into an empty locker on the Princeton. And there were… You know, I left it there, and on I went on my journey. Several months later, the U.S.S. Princeton is torpedoed or bombed. It’s sunk by the Japanese, and it was sunk. The carrier went down. So, here I am at Great Lakes, Illinois, in this big receiving center.

Out of college, which, of course, I didn’t need the hammock. I look at my quarters in this big building in Great Lakes, I see bunks with no mattresses on them. So, there’s a gnarled old quartermaster who’s in charge. He was probably in the Navy for 20 years, and he finally got a good job. And I went up to him and I said, “I’m sorry, but I don’t have any bedding.” “Why the hell don’t you?” I said, “It went down with the Princeton.” “Oh, fella, let me help you. I’ll go get you a mattress.” I mean, you had to tell a little, you know…

Joshua Bell: Well, it was true. It did go down with the Princeton.

Dwight Smith: That’s, that’s the God awful truth. I twisted the truth so it worked for me. And so, I got a bunk, and so forth. So… Oh, guess where I was on VJ Day?

Joshua Bell: Oh, please tell me.

Dwight Smith: You know that photograph of the sailor and the nurse in Times Square?

Joshua Bell: Yes.

Dwight Smith: Yes. Well, it could have been me. I was in Times Square on August 15, 1945, because, at that point, I was attached to the Brooklyn Armed Guards Center in Brooklyn, New York. And, I got a couple of babes together, and we… Nickel fare, we rode the subway into Times Square and had a great time.

Joshua Bell: What do you remember thinking about VJ Day happening?

Dwight Smith: Oh, very pleased, believe me. Very pleased. It meant I didn’t have to go back to the South Pacific.

Joshua Bell: Yeah.

Dwight Smith: So, there I was in Brooklyn. Now, why was I in Brooklyn? Because when I got out of Great Lakes, they sent me to radar operator’s school. Finally, the Navy sends me to a school I can attend and graduate from. They sent me to a radar operator’s school in Point Loma in San Diego, California. The most beautiful place I have ever been, as far as climate was concerned. You get out on the water… A point of land in San Diego, and the cool ocean breezes, and the warm sun, 70 degrees and low humidity, and six weeks of studies to learn how to operate radar…which I did. And I got my certificate, and I needed to be reassigned. Of course, I’m in California, and so they have to reconsign me to somewhere on the East Coast, don’t they? They did. They sent me to the Brooklyn Armed Guard Center in Brooklyn, New York, where my parents were living, at that time. And, it was totally useless to do these things to me, but they did. And, so then, they finally put me on a ship. It was to operate the radar on a merchant ship, because the Merchant Marine companies didn’t have radar yet. Only the Navy had radar. So, they installed radar…little bits of radar were on these cargo ships. So, I was sent down, by train, to Jacksonville, Florida to board the S.S. Thomas W. Hyde, which was a Liberty ship loaded with kegs of tobacco and prefabricated houses, wooden prefabricated houses. We were headed to London, England. And we were both… Tobacco and housing was in need… They needed it. We sailed out of Jacksonville, Florida with this cargo, and I’m the radar operator, and I’m very proud of this. I got a private cabin, because they didn’t know where to put me. Even though I was still a seaman first class, they gave me a private cabin. It used to be the radio operator’s cabin. I dined with the officers.

Joshua Bell: Wow.

Dwight Smith: Yeah. I’m a seaman first class, but the only one on the ship who knew anything about the radar. Joshua Bell: Big time.

Dwight Smith: Yeah, big time. So, I enjoyed that journey, because once I went topside, and I said to the skipper, “Do you want me to show you how this works?” He said, “Ah, I don’t believe in it. Don’t bother me.”

Joshua Bell: Don’t believe in it.

Dwight Smith: So, I had this trip over to London, England and back, at the Navy’s expense.

Joshua Bell: Not bad.

Dwight Smith: And once we got to London, we off-loaded our… This was November, September, October, yeah, September, October, it was ’45. The war in Japan was over. In fact, the whole war was over. We still had a Navy gun crew on the Thomas Hyde, but they didn’t have anything to do except polish their guns. And I didn’t have anything to do because the skipper didn’t believe in radar, so… He was a merchant seaman. So, I said, “Okay. I’ll enjoy this voyage.” And then we… I went ashore with some of the gun and crew buddies, and we saw London, the upside, and London and the downside of London. And we spent a few days there. And, finally, we headed back to Boston, and we had a cargo of troops, returning troops from the war in Europe returning to the United States. They put up bunks in the cargo holds, and we carried troops back with us. So, it was a nice round trip, and once we reached Boston, I think I’ll… maybe I’ll go out on the ship again. I hope so. [Unintelligible 00:47:27] Some officers come aboard with clipboards, and call me down, “Where are you?” And I just told them, “I’m up here.” And so, they came up and interviewed me. They said, “Were putting three men on to replace you. Two to operate it, and one to repair the radar. They are going to be Army men.” I said, “Okay. Whatever.” So, they put me back into, I don’t know, some receiving station somewhere. Oh, I know. I was on the East Coast, right? Well, guess where I’m sent? San Francisco.

Joshua Bell: No way.

Dwight Smith: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. Nothing spectacular, but… So, I reached San Francisco, and I learned that I’m going to be a crew member on the LST-835 landing ship tank in San Francisco. It was anchored off of Alcatraz, there in San Francisco Bay. It had brought back… The war was over in Japan. The war was over, and they brought back on this LST a lot of military gear that was still usable. You know, trucks, and tractors, and other stuff that was over in the islands of the Pacific. And they put it all on this LST, and sent the LST to San Francisco, where they unloaded all this stuff. Now, the Navy said the LST… They used to go up to Portland, Oregon. It will be decommissioned, eventually. So, I’m put on the LST-835 as a radar operator. Again, no interest on the part of any other crew that we needed radar. So, again, I was just a passenger. And we went up the coast to Astoria, Oregon. We put up there for a while. And then we went up the Columbia River to Portland, Oregon, and we tied up there for the winter. This was 1945-46. And I am totally bored. Nothing to do. So, I said to the crew; there’s a yeoman and a storekeeper. Each went ashore everyday together in a Navy truck, not in a big truck, but a Navy truck to run errands. The storekeeper’s going to buy groceries so we can eat on the ship, and the yeoman has got paperwork to go to the Naval headquarters, back and forth. So, the two of them would go ashore every day in this truck. And I went up to them, and I said… They were nice guys, and I said to them, “Would you like to have a chauffeur take you every day?” “Oh, sure.” So, that was my job, to take them ashore, not ashore, we were tied up at a dock, but to take them downtown. And our first stop every day was Union Station in Portland, Oregon to have a… USO to have a coffee and a donut. And we ran our errands and came back. In the afternoon, we had nothing to do, but nonetheless, it was something for me to do, because I was on that LST for the whole winter of ’45-’46, and never saw the sun shine in Portland, Oregon in the winter. But it wasn’t cold or it wasn’t snowy, it was just gray.

And, there I was in Portland, Oregon, and I’m about to be discharged. I finally have enough points to be discharged. And the yeoman says to me, “You have to discharged on the East Coast because that’s where you started out of.” I said, “Oh, Jeez. Another train ride, coast to coast.” I really wanted to hitchhike, because I just wanted to be out of the Navy, now. And I could stop along the way and visit some of my old Navy buddies, who lives in Texas, and lived in Louisiana, and Oregon, Eastern Washington, and so forth. I wanted to stop, you know, make a nice trip out of it.

So, I said to the yeoman, “How do I get discharged out here instead of Boston?” “Well,” he says, “do you happen to have a job out here?” I said, “No, I don’t.” “Well, you have to have family out here.” I said, “No, I don’t.” “Or you could have a car out here.” Ah ha. I whipped out my [unintelligible 00:51:40] wallet, and there’s my registration from my Model-A Ford. Still good. A Vermont registration. The car was up on blocks in my garage in Groton, Vermont. The registration was still valid. So, the yeoman signs all of the paperwork, and I’m discharged in Bremerton, Washington, and I’m paid three cents a mile to drive my car back to Boston. And I pocketed the three cents a mile and hitchhiked. You know, I think my story almost sounds like I had too much fun.

Joshua Bell: That’s fantastic.

Dwight Smith: It is! It really is.

Joshua Bell: It sounds like it was a little frustrating, though.

Dwight Smith: Oh, yes. Oh, definitely.

Joshua Bell: More [unintelligible 00:52:24], perhaps.

Dwight Smith: Well, there were many places which would frustrate you. And, particularly when the Navy brass is making decisions for you, and you wonder where they got their brains from. We groused about it, you know, but, you know, in two years eleven months, I crossed the Atlantic Ocean, I crossed the Pacific, I mean, I went from California to Oregon by boat, and I was out in the South Pacific. And all that and a full college year at Dartmouth College. Two semesters of a regular college year. And radar school, and… To think about it, two years eleven months, I crammed all of that stuff in?

Coast to coast and doing everything. And having met my lady friend. That was during…while I was in the Navy. I met her for two different weekends, and then I was off to the seas again, and we corresponded by mail. And, finally, when I hitchhiked back, Christmas of ’45, we were still… We hadn’t seen much of each other. And we made plans, and the following summer, I went back to college, and she had a summer job near, but I only… We got engaged and married, and now I’m the – we together, produced five children. And now, she’s passed away, but I have nine grandchildren now, and eleven great grandchildren, and it’s pretty amazing to me. I’m 91 years old, and I don’t feel it, and I don’t look it.

Joshua Bell: No, you certainly don’t.

Dwight Smith: I am thoroughly… Feel that I am fortunate, because I’ve got my health, I have a new lady friend who’s… We’re very close. We just enjoy each other’s company. I have a daughter and son-in-law whose very close to me, living five miles away from here, and where I live. And I have a son and his family living over in Bridgton, Maine, which is about 25 miles from here. And I have a son and family living in South Portland, Maine, which is about 60 miles from here. And I have a son and a daughter-in-law living out in Battleground, Washington, which is… They both work in the city of Portland, Oregon. But that’s all I have today, and I’m so pleased with it, that I’m here and the shape I’m in. I just feel fortunate.

Joshua Bell: Absolutely. I wanted ask, what are you most proud of about your time in the service?

Dwight Smith: I’m most proud of the fact that I served in… I’m a combat Naval veteran, and I did my, whatever I had to do, and I did it willingly. I didn’t have much choice, but I mean to say, though, that once I was in this dangerous situation, I held up very well. And I… I can’t say I didn’t really enjoy the ten trips across the country. There’s a tale in that one, too. Let me tell you.

Joshua Bell: Oh, please, please.

Dwight Smith: I chose… Because I’m a rail fan, and my whole working history was in the railroad business, that I took different routes every time I crossed the country by rail. The same rate fare, but I took different railroad company’s routes. And the most popular one was from New York to Chicago on either the New York Central or the Pennsylvania Railroad. And then, from Chicago to the West Coast, the usual route was Chicago and Northwestern to Omaha, Nebraska, and the Union Pacific to Ogden, Utah, and the Southern Pacific on to California. And that was the typical route for everything moving from Chicago to the West Coast.

There are exceptions, of course, but, basically, that was the major one. My first time gong west on that route, like, we’re in the some railroad station in Chicago, ready to board this train that’s going to take us to California. And they said, “For you servicemen, we have a special deal for you today. We’re going to allow you to have your own coach, and you’ll get on now, before the public gets on the train.” Whoopee-doo. They put us on this old cattle car that had kerosene lamps, and no air conditioning, and stiff-back seats.

And then they opened the rest of the train with streamline cars, with reclining seats, and the air conditioning in the [unintelligible 00:57:07], and that’s how they rode to the West Coast. I said, “This is bullshit. I’m not going to do this again.” So, the next two times I did, I was in that same station, and the same offer was made to me, I stayed with the civilians, and waited for them to be called to board the train, because they’re not going to sit in those comfortable cars. So, those three trips, I learned on the first trip what not to do, and the second two trips were just fine. It’s just you have to work the system as well as you can.

Joshua Bell: Absolutely.

Dwight Smith: And, yeah, I did, and I… Overall, it was not a bad situation that I had. I mean, yes, it was not very safe out in the South Pacific, but I…

[End of recorded material 00:57:52]

June 27, 2016

[Start of recorded material 00:00:00]

Joshua Bell: Today is June 27, 2016. I’m Josh Bell, park ranger with the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area. I’m joined, again, by Dwight Smith, who has been telling us about his experiences in the Navy. How are you doing today, Mr. Smith?

Dwight Smith: I’m doing fine. I’m in good health and good… I feel well.

Joshua Bell: Excellent. And it’s all right if we record our conversations like we did last time.

Dwight Smith: It is okay.

Joshua Bell: All right. Excellent. So, we covered quite a lot the last time we talked, and I was wondering if there was anything that I didn’t ask you that you’d like to share with the Historic Area?

Dwight Smith: Yes. I would like to discuss, briefly, each of the three ships I sailed on. What were they doing while I was on there? I mean, why was I on there, and what were they doing? I think I’ll start with the third one and work back, because it gets more exciting going back.

Joshua Bell: Sure.

Dwight Smith: The third ship that I sailed on was a LST-835, which is a landing ship tank. And I boarded it in… I got to look at my records, here. I boarded it in 1946 in San Francisco Bay. It was out in the Bay after it had come… The war in Japan was over, and LST was in San Francisco, and it brought back from Japan, retrievable U.S. military gear. They just loaded up the stuff that was still usable, and brought it into San Francisco. And they off-loaded it. And then it was empty, and it was going to head up the coast to Portland, Oregon to be decommissioned. They needed a crew to get on it, and I was…happened to be at a Navy waiting station, if you will, in Treasure Island. And they said, “We’re assigning you to be the radar operator on LST-835.

Joshua Bell: Oh, I’m sorry, there was a blip there. What was your duty?

Dwight Smith: Radar operator.

Joshua Bell: Radar operator, okay.

Dwight Smith: That’s the time I had a rating of radar operator third class. And so, I boarded the ship, and we sailed up the coast, first to Astoria, Oregon, and then to Portland, Oregon, where we tied up. I had absolutely nothing to do on the ship other than look at the radar while we were in route to Oregon. And we got into Portland, Oregon in the fall of 1945, and then we tied up there, and I sat on that LST, and I had absolutely nothing to do. I was awaiting another place to be discharged.

You see, you had to earn so many points, based on time and other factors, to be discharged. So, I was waiting to be discharged, and I had nothing to do on this ship. And I noticed that we were tied up at a dock in Portland, Oregon –– Swan Island, Portland, Oregon. And the ship’s yeoman and the ship’s storekeeper went ashore every day to do errands in the downtown city of Portland. The yeoman had Navy paperwork to exchange with the Navy base in Portland. And the storekeeper had to go into town to buy groceries for the LST dining hall. And they went in…took a Navy truck adjacent to where we were tied up, took a Navy truck and went into town every day.

And I said to them, “Would you like to have a chauffeur?” They said, “Sure.” So, I then drove them into town every day while they ran their errands. So it gave me something to do, and it gave them a little bit of help. And I said to them, I said, “Well, what do you do every day?” Well, they said, “First we go to the Portland Union Railroad Station, and the USO in there has coffee and donuts. So that was our daily routine, the coffee and donuts, and then we ran our errands and came back to the ship.

Now, it’s getting close to my discharge time. There I was out on the West Coast, and my home is on the East Coast –– This is the way it was in the Navy. And they said to me, “We’re going to have send you back to Boston, on a troop train, for your discharge.” And I said, “I’ve already crossed the United States six times by train, seven times by train, coast to coast, and I would like…

Joshua Bell: And this is when you hitchhiked.

Dwight Smith: That’s correct. And this is when the ship’s yeoman said to me, “You ready to be sent off to Boston on the train?” I said, “No. I’d like to be discharged here, at Bremerton, Washington.” He said, “Well, you can’t unless you have one of these three things to pass. Do you have any family out here?” I said, “No.” “Do you have a job out here.?” I said, “No.” “Do you have a car out here?” And without a further word, I reached in my pocket, pulled out the current registration I had for my Model-A Ford, valid. I didn’t tell him that the Model-A Ford was in Groton, Vermont, up on concrete blocks, waiting for my return. So, I get discharged in Bremerton, Washington, and hitchhiked home. This time I took two weeks to return to the East Coast by my thumb, because I wanted to visit friends along the way. And I had a shipmate that had already been discharged down in Texas, and another one in Spokane, Washington, and Washington D.C. So, I made these stops when I was hitchhiking across the country, and it took me a full two weeks to do it.

Joshua Bell: What were the names of your friends that you stopped to see?

Dwight Smith: I don’t remember. They were shipmates of mine, and they were already discharged. So I visited them, and I saw the country, and it was a very nice trip. And that was it. I was out of the Navy. But my lady friend, back on the East Coast, was very interested in me, and I was very interested in her. And I said to her, “I may go back to sea.” And she pointed to me and said, “The sea or me.” That was the end of my naval career, and seagoing career, and I went into the railroad business, which I stayed in until 1999.

Joshua Bell: What did you do in the railroad business?

Dwight Smith: Well, I worked for the Boston and Maine Rail Road in New England for 26 years, in freight marketing, freight sales, freight traffic department. And they were spiraling downhill, so I quit. I was not downsized. I did not get fired. I just quit. And I said, “I can do better by myself running my own railroad.” Now, there’s a step. So after, I really fell into luck, and I ended up starting our first train on the Conway Scenic Railroad, 11 miles long, in 1974. It was called Passengers Only; a little, short, you know, one-hour round trip in the summer, in North Conway, New Hampshire, where I live now. And it was very successful.

Joshua Bell: I have been on that train.

Dwight Smith: Have you?

Joshua Bell: Yeah.

Dwight Smith: Well, good. Good. I hope you paid for your trip.

Joshua Bell: I certainly did.

Dwight Smith: Because I’m living off of my… I sold my last share of stock in it in 1999, and I’m now living off the income of my investment. It’s been… It was very, very fascinating job. That was a job I enjoyed having, and enjoyed the challenges of starting from ground zero on a business. My wife and I were side by side. She ran our gift shop, and I ran the railroad, and my son ran the snack bar, and it was just…And, mostly, summer employees were… Because we only ran in the summer and into October. And so, most of my help were either college students, or school teachers who had the summer off, or retirees. And every one of them, though, enjoyed the job, because they all liked to work for a railroad. From track workers to the conductor on the train. And people would ask me, “What is your job here? Are you a conductor or engineer?” I said, “No. I stay here, back in the office, and count the money.” But it was a fascinating career, and I really was very, very fortunate to be enabled to do it. But, back to the Navy. That was the reason I sailed on the LST-835 was because they had nothing else for me to do. But to go back to the next ship backwards, here. The next ship was the S.S. Thomas W. Hyde, which is a Liberty ship, and Liberty ships were made, by the dozens, in shipyards throughout the United States, during World War II to help balance out the number of merchant ships that were lost to German submarines, or Japanese submarines. So, I was assigned as a…I was now a radar operator, and I was assigned to the Thomas W. Hyde, which is a merchant ship with a merchant crew, but they still had onboard the Navy Armed Guard, which were some Navy personnel, and they had some guns mounted on these merchant ships. This was in the fall of 1945. The war is over in August of ’45 and I boarded this ship in September of ’45. I boarded it in Jacksonville, Florida, and it was really on a mercy trip, because they loaded the ship down to Florida with kegs of tobacco, and pre-fabricated houses, which we delivered to London, England. Of course, a lot of homes were bombed out over in England in 1943-44, and these pre-fabricated houses were very welcomed. So, it was a mercy trip, really. And, once we got to London, England, we tied up and stayed there for a while. And when we left, we had a cargo full of returning troops. In other words, when the cargo facilities were emptied, they put in metal bunks, three deep, probably, and we took, you know, several hundred troops back to the United States.

And we came back to Boston. Again, here I was, I was a radar operator, and just as we were leaving Jacksonville, Florida, I said to the skipper, “You want me to start using this radar the Navy just installed on your merchant ship?” He said, “Oh, no. I don’t believe in it.” So, I had a cruise to London, England and back, with absolutely no duties, because he was not interested in… He was a merchant skipper, but not interested.

But what had happened at this point in time was, the U.S. Navy had developed workable radar, but none of the merchant ships really had any of that. So, the Navy put these radar - fit machines on these merchant ships, along with a Navy personnel –– me. And it would have been great if we needed it, but I guess we didn’t. So, I enjoyed the tour to England and back.

And, once we reached Boston, I said, “This is a good deal. I’d like to stay on this ship for a while.” Well, a couple of officers onboard the ship, called for me and told me that I would have to leave the ship because they’re putting on three people to replace me. Two to operate the radar, and one to repair it. Now, these were Army guys, not Navy. I said, “Oh, okay.” So, there I am in Boston, Massachusetts, a few miles, not many miles from my home, and the Navy decides that a better place for me would be back in California, again.

Joshua Bell: Oh, naturally.

Dwight Smith: Oh, naturally. Well, that’s how I ended up on the LST-835 in San Francisco, because it’s as far away from Boston as they could find to get me. Now, back to number one, the U.S.S. South Dakota. Battleship 57 –– BB 57. Its goal was to annihilate Japanese Navy, annihilate occupants of Japanese-held islands in the South Pacific, which they were quite good at doing. And I was just out of boot camp, ten days leave at the home, and just out of boot camp, and they shipped me down to Norfolk, Virginia. And there was this big battleship in dry-dock, it had just come back from the North Atlantic, because it was helping the British] fleet guard the merchant ships that were headed for Murmansk, Russia, which was above the… What’s the word? Above the Arctic Circle. If you go up the coast of Norway, and around the top of Norway, and you end up at a port in Russia –– Murmansk. And that was where tons and tons of ammunition and land tanks, and all kinds of stuff were delivered to the Russian people because they were on our side against Japan, and against Germany. So, the South Dakota was working with the British fleet for a while, and then they were discharged from that, and sent down to Norfolk, Virginia to be in the dry-dock for a little bit of work. And that’s when I boarded the South Dakota. And, mind you, I was just out of boot camp. I did at home for a ten-day leave. I didn’t know beans about Navy ships or whatever might happen next for me. But the South Dakota needed… They let about 200 of their seaman that had been on the ship up until…with the British fleet. Before that, the South Dakota had already been out in the South Pacific. And when they reached Norfolk, they let about 200 of them go onto other duties, and didn’t have to stay on that particular ship.

So, I was one of about 200 who were assigned to the South Dakota. We lined up on the fantail, and one evening, as we arrived the first day we had on the ship. And officers were telling each one of us what department we were going to be in, what division we were going to be in. Are we going to be peeling potatoes, or swabbing the decks, or chipping paint, or manning those anti-aircraft guns, which were totally exposed to the weather, and the bombs, and so forth? And so, I was going to be assigned to one of those divisions. Then one of the officers said, “Anybody out there have any high school math?” “No,” the people around me, “Don’t volunteer. You never volunteer in the Navy.” I said, “Well, I’m going to.” I raised my hand, and I got assigned to the Fire Control Division, which is quite technical.

And so, I spent nine months in the Fire Control Division as a Fire Control-man, striker, they called them. I was a seaman first class. Off we went through the Panama Canal and into the South Pacific. And, I entered a new part of my life, because here I was a crew member on a battleship in the South Pacific in 1943, when things were not going very well down there. There I was, a vital crew member on this ship. My battle station was down in the bowels of the ship, working with a computer.

There was twin 5-inch mounts, and there were two of them manned by… They had the director up topside, and there is a room, a rotating room where you had the optics. You could look in the magnifying optics and see the airplanes, and so forth. And, down in the plotting room, where I was, we had a computer, which was all vacuum tubes. Hotter than Hell down there.

And the guys with the optics up topside were feeding us information by phone. And I, you know, I had earphones on me, and I was listening to them telling me these facts, and I’m cranking data into the computer. So that was what I did when we were being attacked.

Joshua Bell: And what did the computer compute?

Dwight Smith: Damned if I know. Oh, how to aim those twin 5-inch guns.

Joshua Bell: There you go.

Dwight Smith: In other words, they feed in the temperature, and the humidity, and wind direction, and all these factors, so that when you pull the trigger on the gun, topside, you’re going to hit the target, because we entered all this data. Hopefully, you were going to hit the target that’s moving very swiftly.

Joshua Bell: And what were…? Were the 5-inch guns anti-aircraft?

Dwight Smith: Yes.

Joshua Bell: Yeah. Okay.

Dwight Smith: And they were bilingual, they were anti-aircraft and they could also do other ship-to-ship things. When I was out there, it was for anti-aircraft.

Joshua Bell: Were there other people in the Fire Control room with you?

Dwight Smith: Oh, yes. It was crowded. We had lots of guys doing the same thing for other guns. I had one…two sets of twin 5-inch guns that I was directing, helping to direct. And the ship had ten of these twin 5-inch gun facilities. Ten of them, I think. And then the ship also had nine 16-inch guns, which were not used for anti-aircraft but for shore bombardments, and they had their own plotting room. And it was noisy. I could hear things down there, and feel things down there, but I never saw anything really, during my battle station. But, the rest of the cruise, I was topside on one of those 5-inch directors, which are a piece of armor-plated machinery that has the optical finders up there. And my day, every 8-hour day, night, day or night, I was assigned to man one of those facilities. But, actually, when the battle station was called, you know, you got to go get to your battle station, I dropped from that site down into the bowels of the ship, where my battle station was. So, it means that I spent my work time, eight hours a day, sitting on top of that gun director topside, reading my manual on how to become an excellent Fire Control-man, and looking out over the Pacific Ocean, and there’s a… You look out from where my seat was… We were guarding primarily aircraft carriers. There were also cruisers out there, and destroyers, and destroyer escorts, and hundreds of ships, as far as the eye can see. There was… Well, it was entertaining, if nothing else. But, it was scary at times, because you were guiding these aircraft carriers, and you see these airplanes being launched off the carriers, and landing on the carriers, and some of them missing. They… All over the drink is dead, and that was, kind of, sad. But, nonetheless, we were doing a very, very… A very special phase of our battleship’s life was to protect, with our anti-aircraft guns, to protect those aircraft carriers. And the other thing we did while we were in the South Pacific, go to these little islands, offshore, those little Japanese-held islands. And with our 16-inch guns, we would fire 16- inch armor at the islands, just trying to blow up the Japanese quarters, or whatever, before our troops landed.

In other words, our duty with those 16-inch guns, was to soften up the islands before our people landed on them. And that was a… That was interesting, and I was down, again, in the plotting room for that, because that’s where my battle station was, and we were at battle standards when we were bombarding these islands. So, that was the only…really part of the World War II that I really felt I’d done something.

Joshua Bell: Mm-mmm. You mentioned that you have several battle stars.

Dwight Smith: Four.

Joshua Bell: Four. Which battles?

Dwight Smith: Well, it says so on my… Just a minute, I’m going to let you [unintelligible 00:24:19] exactly. And I’m going to be sending you some of these documentations.

Joshua Bell: Oh, that will be great.

Dwight Smith: Okay. First history of the battleship... While I was aboard the ship. It departed Norfolk, August 21, 1943, and I departed from it in May of 1944 to come back to the college training program. In between… After I got onboard, we went through the Panama Canal, and we stopped at Pearl Harbor, and finally arrived at Havana Harbor at [unintelligible 00:25:27] Island in the New Hebrides Islands. And we went island hopping. Fiji Islands had started new campaign of island hopping. The next offensive for the Japanese included the South Dakota began with the attack and liberation of the vast Gilbert and Marshall Islands. Starting in November of ’43. Specific targets of the Marshall Islands include Kwajalein Atoll, Roi, R-O-I, Taromaaoelap T-A-R-O-A-M-A-O-E-L-A-P, and when that operation was secured, we steamed out to bombard the island of Namur, after which she escorted the carrier, Bunker Hill, back to Efate in the New Hebrides. Now that’s the balance of 1943.

And in ’44, I’m on the ship until May. We were screening carriers. Then she took part in the mid-February upon the primary Japanese forward anchorage of Truk. It had devastating results for the Japanese Navy. The South Dakota would continue carrier screening duties during the raids on the Marianas, with strikes upon Tinian, Saipan, and Guam, and returned to Majuro by the end of February of ’44.

In March of “44, we went on to the Caroline Islands of Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Walea. The battleship returned briefly to Majuro to resupply, and then departed to cover air strikes against various airfield targets, to cover U.S. troop landings on the Hollandia and along the points of the New Guinea coast. Later April, the South Dakota participated in a second strike upon the Japanese base at Truk. In May of ’44, the South Dakota was back in Majuro on the Marshall Islands for minor refits and to prepare for the invasion of the Mariana Islands. At Majuro, Dwight Smith left the South Dakota, and boarded the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Princeton for passage to Pearl Harbor, and the first leg of his journey back to the U.S.A. and the V-12 College Training Program. So that’s where I was.

Joshua Bell: Excellent. You mentioned the V-12 program. What was your living situation like?

Dwight Smith: It was at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, and we V-12 all were in uniform, and we had college dorm rooms. I had three roommates. There were four of us in a two-bed… Normally, in peacetime, just a two-bed room. Put two double bunks in the room, and so there were four of us living in the room in the college, one of the college dormitories. And…

Joshua Bell: You must have got up to some sort of antics.

Dwight Smith: Well, it was a little bit cramped, but the other three guys and I got along very well. But I miss… In that entire battalion of V-12 students at Dartmouth College, everyone except me, is either right out of high school or college, directly into the V-12 Program wearing Navy uniforms, but this was their first Navy experience. I was the only one in the whole group that had four battle scars already.

Joshua Bell: You were the old man.

Dwight Smith: Yeah. I was the only one that had been to sea. I was the only one who was a seaman first class. Think about that. I mean, my God. Well, I have a picture I’m going to send you. It shows the whole battalion come to one dormitory, anyway. About a hundred marching across the green at Dartmouth College. And there, leading the pack, is one guy who was really there, and I’m second of line, carrying the flag. The rest of them are eight abreast, marching. And I was standing in front of this…parading in front of this group, holding the flag, and one of my roommates was appointed to be the boss. I mean, it’s just amazing to me. Joshua Bell: So, what did you do with your spare time, or did you have spare time, I guess would be a better question?

Dwight Smith: Yes, we were college students, and we had weekends off. We didn’t have summer vacation, but we had weekends off. Let’s see, I had that car that was up on blocks when I got discharged. I had the car down at the V-12. And my home was 40 miles away. And my roommates and I would go down to Northampton, Massachusetts on one of our weekends to see the girls down at Smith College. And we’d go up to Montreal. We did real college-type stuff on the weekends. But we were in uniform, and we had to take certain courses. But we were also free to take elective courses, as well. And we were in uniform at all times. We were in the Navy.

Joshua Bell: Did you find the program of study rigorous?

Dwight Smith: Yes. We had… We all had to take… What’s the word? Physics I. That was where we met at a big amphitheater, and one professor is, you know, lecturing to about 50 of us, or so, in the room. And his name was Dr. Merch. And we finally began calling it, this class, Merch’s Mystery Hour, because Physics I, for most of us, was totally a different world. But we got through it okay. I got my diploma for my two semesters at Dartmouth College.

Joshua Bell: So you finished the program?

Dwight Smith: Yes, the V-12 Program.

Joshua Bell: You finished the V-12 Program. Excellent.

Dwight Smith: But that was… I had already had two years of junior college, which counted towards my full college. So, this is my third year of college. And then when the V-12 Program for us ended, I was assigned to a 90-day wonder school down in New York Maritime Academy at Fort Schuyler in the Bronx, New York. And that’s where you’re supposed to come out of that class as an ensign. Well, I was… It was a very, very intense course. Believe me, you were gone… I mean, there was hours of drilling, and classes, and studies, and, you know, like, from 6:00 am to 6:00 pm. It was grueling. Well, I was doing okay for the first 30 days, when I came down with German measles. Now, I don’t know why I came down with German measles. I don’t know why they put me in a Navy hospital with German measles, but I was sent to a Navy hospital for… I think I was there for a week. And, of course, this was a very intense course. You lose a week, you’ve lost it. So, I came back to Fort Schuyler, the Navy nautical school, and found my name on the bulletin board as being no longer part of this class, along with several others who probably failed physically, mentally, I mean - They probably failed not because of German measles, but they failed because of the scholastic abilities.

Joshua Bell: Did that ever happen in the V-12 Program where people were dropped out at Dartmouth?

Dwight Smith: Yeah. This was… Yes. No, not the V-12 Program. I think most… Well, there could have been. I know, because we were…got a certificate that we had fulfilled out course requirements at the V-12. But this was the midshipman’s school…

Joshua Bell: Right.

Dwight Smith: … The 90-day wonder school, and I lasted 30 days. So, we were around the East Coast, so they sent me to Chicago, my next place in the Navy. And, let’s backtrack a little bit on this story, because I’ve told you earlier that I was a passenger on the U.S.S. Princeton from Majuro when I was on the South Dakota to…

Joshua Bell: Oh, yes, yes. And it was… And then the Princeton was sunk.

Dwight Smith: Yes.

Joshua Bell: And you were issued new bedding.

Dwight Smith: Yes. This was in Chicago after I… Yes. I left my bedding on the Princeton, and I got into the huge bedroom out at Great Lakes, Illinois. Great Lakes Naval Base. I see the bunks with no bedding on them. And I went up to the boatswain in charge. You know, they’re old time, longtime, tough old Navy men. And I said, “Sir, I don’t have any bedding.” “Why the hell don’t you?” That’s when I told him it went down with the Princeton. He threw his arms around me, he says, “Okay, fella. I’ll get you some bedding.” I didn’t lie.

Joshua Bell: You didn’t lie.

Dwight Smith: No, I didn’t lie.

Joshua Bell: You didn’t lie. I’m trying to think of other questions I can ask you, but I think we might have… The only other thing I can think to ask you is if you…if you recall any of the guys you were with, or any stories from your time in Dartmouth?

Dwight Smith: Stories? I think I was - only when I had real stories to tell. [Unintelligible 00:36:46] the V-12 Program, because they were all just out of high school or freshman college. But… No, I… Now, I’ve done programs with the local World War II Historical Museum at Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, and I’ve done a program with a couple of them at the Conway Historical Society telling my tale. And I just did it for the local men’s… Congregational Church men’s Friday breakfast. They have different speakers every Friday morning, and I gave them a program the other day. Some of the other veterans there were quite interested in my little tales. I never go into one of these and give a program on how I won the war. I go into what it was like from the eyes of an 18-year-old.

Joshua Bell: Absolutely.

Dwight Smith: That’s what I’ve been telling you, is what I saw of the Navy as through my mind and through my eyes.

Joshua Bell: Well, I appreciate that very much, and on behalf of the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area, I really have to thank you for sharing your story with us, and we’ll absolutely make sure that, you know, we preserve it and share it with future generations. Because what your generation did is quite large and significant, and…

Dwight Smith: I’m fully aware of that, and I’m always… I’m sadly now aware of the fact that there are very few of us World War II veterans still around. That is sad. But I did what I had to do, and I did it because I felt I wanted to. And, I wasn’t a hero, but I was there doing what I was…they asked me to do. And, I also think that the nearly everyone in the United States was behind us. That is something that hasn’t happened in any of the wars subsequent to that. That one was 100% backed by everyone in our country.

Joshua Bell: It was.

Dwight Smith: And I’m proud of what I was able to do. Other than my father who was torpedoed and sunk in 1942, I have had no family members involved in any military activities. And, if this is… If I’ve answered all your questions, I’d like to say I’m going to send you these pictures I promised, and also some of the fact sheets.

[End of recorded material 00:39:47]

-

Dwight Smith Interview Part II

Dwight Smith served in the Navy during World War II. He was never stationed in the Aleutian Islands, but he recounts many interesting stories from his time onboard the USS South Dakota, SS Thomas W. Hyde, and LST-835. After the war he had a family and a long career with railroads. This is part II of his interview.

- Credit / Author:

- NPS/Joshua Bell

Interview with Radar Operator 3/c Dwight SmithAleutian World War II National Historic Area Oral History Program

June 22 & 27, 2016 Intervale, New Hampshire

Interviewed by Joshua Bell, Park Ranger, National Park Service

This interview is part of the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area Oral History Project. This interview was recorded with the interviewee’s permission on a digital recorder. Copies of the audio file are preserved in mp3, wav and wma formats and are on file at the offices of the National Park Service in Anchorage, Alaska.

The transcript has been lightly edited.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

June 22, 2016

[Start of recorded material 00:00:00]