Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 13, No. 1, Spring 2021.

Article

Meet Deb Wagner—Petrified Forest National Park’s Paleontology Lab Manager

Deb Wagner and Diana Boudreau

Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

NPS photo by Deb Wagner.

Deb Wagner was hired in May 2020 to manage the fossil preparation lab at Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. From preparing Late Triassic fossils of all sizes to maintaining lab equipment and supplies to keeping track of newly collected specimens, Deb plays an important role in conserving and curating the world-renowned Late Triassic fossils found at the park.

Your official title is a Museum Specialist. What exactly does that mean?

The Museum Specialist at Petrified Forest (PEFO) serves as the Lead Preparator and Lab Manager for the park. On a personal level, it means a whole lot more. The National Park Service (NPS) has always been a big part of my life and working here is unlike anything I could have imagined. Some of my earliest memories are vacations to the Great Smoky Mountains and Mammoth Cave. A family trip to Big Bend when I was a teenager solidified my desire to see as many parks as possible. I first visited PEFO during a summer road trip nearly 20 years ago, we must have gone to 15 parks that summer. Paleontology was still very new to me and I felt a strong connection to PEFO. I have followed the work of the NPS Museum Management Program throughout my career, often referring to the Museum Handbook or Conserve-O-Grams when needed. When the opportunity arose to join the NPS, and better yet PEFO, I knew that I couldn’t pass it up!

What was it about PEFO that really sparked your curiosity?

Working in the Triassic! I’ve always been interested in evolutionary patterns and the forces that drive them. The Triassic was a time of rich diversity and there were so many weird and unusual vertebrates that evolved to fill different ecological niches. It’s exciting to prepare a specimen when you don’t necessarily know what the outcome will be.

Now that you’ve been working at PEFO for almost a year, what does an average day look like for you and have you faced any new challenges?

Starting a new job during a global pandemic has been a big challenge and has impacted what my average day looks like. Everything from organizing an interstate move to getting to know new coworkers is more complex right now. To maintain social distancing, we limit the number of individuals in the lab which makes collaboration difficult, but not impossible. There is a lot of planning and juggling involved, but we make it work. I tend to start every day the same way: emails, making sure everything in the labs are in order, checking in with the Museum Curator and Paleontologist regarding research priorities, and determining a plan for preparation projects. I don't seem to spend as much time actually sitting down at the microscope to prepare fossils as I would like, but if all goes well, I can spend a good portion of the day sitting at a scope preparing specimens.

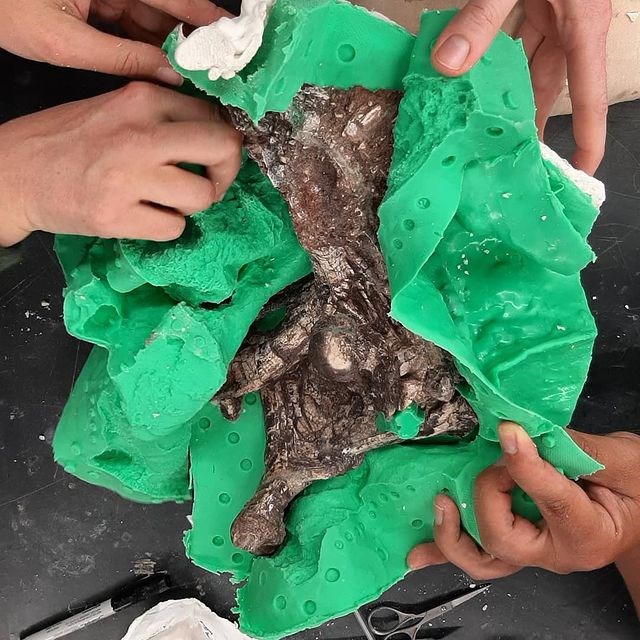

NPS photo by Diana Boudreau.

Speaking of preparing specimens, what types of projects have you been working on since you started?

My biggest project so far is the molding and casting of a large Smilosuchus skull. Since I have spent the majority of my career working on very small animals, I find the task of molding a 3-foot-long skull a bit daunting. At the same time, I welcome the challenge. I have been able to refine my techniques and gain valuable experience by applying new methods and materials to the project. I also do my fair share of micropreparation and microsorting. The very first specimen from the park I worked on was a dinosauriform scapulocoracoid (shoulder blade), a bit of a rarity around here compared to other vertebrates. I’ve spent time on nearly all the “-saurs” including aetosaurs, pterosaurs, trilophosaurs, etc.

So it sounds like small fossils are kind of your specialty!

Definitely! I specialize in micropreparation, which means manual preparation of fossils to the level of detail requiring the use of a microscope. While you can prepare larger specimens this way, I tend to focus on the really small ones. Think tiny rodent or lizard jaws.

NPS photo by Deb Wagner.

That sounds pretty challenging. How and where did you develop the skills to prepare such small fossils?

The majority of my training was at The Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois. I was there for 9 years and this is where I developed a strong foundation in fossil preparation. I worked on specimens from the Ordovician to modern-day, from every continent (including Antarctica!), and even traveled to Beijing to begin preparation and train Chinese technicians to continue the work on a large long-necked reptile called Tanystropheus. I left The Field Museum to pursue a M.S. in Museum & Field Studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder. While I was a student there, I worked as a fossil preparator and a collection assistant for both the vertebrate paleontology and zoology collections. My work as a collection assistant was invaluable and strengthened my passion for specimen conservation and museum collections. In 2014, I joined the team renovating the National Fossil Hall at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. From there I moved to Texas, where I was the Chief Preparator and Lab Manager for the University of Texas, Austin before moving to PEFO.

Wow! You have worked with fossils in so many different ways and in so many different places. Was there a place or moment when you realized you wanted to pursue a career in paleontology, specifically fossil preparation?

My interest in paleontology started during my senior year at The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign when I took a class called the “History of Life”. I had always been interested in science and nature but struggled to find the right fit for me. I was about to graduate with a B.S. in Biochemistry knowing that it wasn't what I truly loved, and something about this class sparked my interest. After graduation, I moved to the Chicago area and began volunteering at The Field Museum to gain a better understanding of the study of paleontology and the various career paths available. While at The Field Museum, I was trained in vertebrate fossil preparation and was hired full-time soon after.

NPS photo by Deb Wagner.

As you reflect back on your career journey, are there certain fossil memories that really stick out in your mind?

My most memorable experiences are not necessarily individual fossils, but rather the moments of discovery. For example, the collective excitement of working together in a quarry when we spot something unexpected, or working side by side with researchers to piece together a mystery in the lab.

What advice do you have for those reading who may be interested in pursuing their own moments of discovery?

I would say to follow your passion. If you have the means, see about volunteering for a museum or university to see what interests you the most. All branches of science involve creative thinking and problem solving, so if you are one of our younger readers think about joining a STEAM program. And finally, get outside and explore! If you see a plant or animal you don’t recognize or don’t know much about, make some observations and look it up when you get home.

Related Links

- Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- NPS—Fossils Through Geologic Time

- NPS—Fossils and Paleontology

- NPS—Geology

Last updated: February 6, 2023