Last updated: September 8, 2021

Article

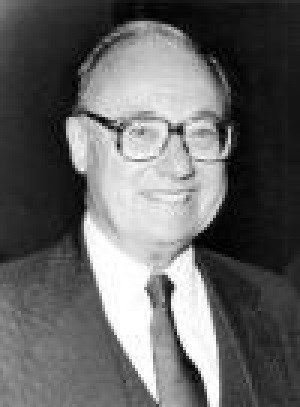

Dr. Benedict K. Zobrist Oral History Interview

NPS

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. BENEDICT K. ZOBRIST

AUGUST 30, 1990INDEPENDENCE, MISSOURI

INTERVIEWED BY JIM WILLIAMS

ORAL HISTORY #1990-6

This transcript corresponds to audiotapes DAV-AR #4135-4140

HARRY S TRUMAN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

EDITORIAL NOTICE

This is a transcript of a tape-recorded interview conducted for Harry S Truman National Historic Site. After a draft of this transcript was made, the park provided a copy to the interviewee and requested that he or she return the transcript with any corrections or modifications that he or she wished to be included in the final transcript. The interviewer, or in some cases another qualified staff member, also reviewed the draft and compared it to the tape recordings. The corrections and other changes suggested by the interviewee and interviewer have been incorporated into this final transcript. The transcript follows as closely as possible the recorded interview, including the usual starts, stops, and other rough spots in typical conversation. The reader should remember that this is essentially a transcript of the spoken, rather than the written, word. Stylistic matters, such as punctuation and capitalization, follow the Chicago Manual of Style, 14th edition. The transcript includes bracketed notices at the end of one tape and the beginning of the next so that, if desired, the reader can find a section of tape more easily by using this transcript.Dr. Benedict K. Zobrist and Jim Williams reviewed the draft of this transcript. Their corrections were incorporated into this final transcript by Perky Beisel in summer 2000. A grant from Eastern National Park and Monument Association funded the transcription and final editing of this interview.

RESTRICTION

Researchers may read, quote from, cite, and photocopy this transcript without permission for purposes of research only. Publication is prohibited, however, without permission from the Superintendent, Harry S Truman National Historic Site.ABSTRACT

Dr. Benedict K. Zobrist was the assistant director of the Harry S. Truman Library for two years before becoming the director in 1971. He retired in 1994. As director, Zobrist worked to develop the library as a research institution. At the request of Margaret Truman Daniel, he directed his staff to complete an inventory of the Truman home in 1981 and 1982, then oversaw the transfer of the home from the National Archives to the National Park Service after Bess W. Truman’s death in October 1982. Zobrist discusses his relationship with Harry and Bess Truman, his work as director of the Truman Library, and his memories of National Park Service employees with whom he worked to develop Harry S Truman National Historic Site.Persons mentioned: Harry S Truman, Philip C. Brooks, Margaret Truman Daniel, Edgar Hinde, Sr., Bess W. Truman, E. Clifton Daniel, Jr., Rose Conway, Paul Burns, Lyndon B. Johnson, Wallace H. Graham, Paul Miller, Tom Evans, Ernest Connally, Hazel Graham, Arthur Mag, Donald H. Chisholm, Norman J. Reigle, Thomas P. Richter, Pat Kerr Dorsey, Elizabeth Safly, J. Edgar Hoover, May Wallace, Sue Gentry, Ardis Haukenberry, Thomas G. Melton, Robert L. Hart, Ike Skelton, Tom Eagleton, Steve Harrison, Clay Bauske, Samuel Gallu, Ronald Mack, William Southern, Mamie Eisenhower, and John Whitman.

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. BENEDICT K. ZOBRIST

HSTR INTERVIEW #1990-6JIM WILLIAMS: This is an interview with Benedict K. Zobrist. We’re in the conference

room at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, on the morning of

August 30, 1990. The interviewer is Jim Williams, a park ranger at Harry S

Truman National Historic Site, and also present is Michael Shaver, a

museum aide at Harry S Truman National Historic Site.

First of all, Dr. Zobrist, I’d like to know if you are a native of

Independence?

BENEDICT ZOBRIST: No, I’m not. I’m a native Illinoisan. But a Midwesterner. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: Could you describe briefly your education and employment experience before

coming to work for the National Archives?

ZOBRIST: [chuckling] How many hours do we have? You can take that one off the

tape. In my education I have a B.A., an M.A., and a Ph.D., all in history, plus

postdoctoral study at, oh, at least six institutions. And I’m also proud of the

fact that I have also been through the senior executive program at the

government in Charlottesville.

In my background, as far as my professional experience is concerned,

I started with the Library of Congress in their manuscripts division, and so

that’s probably the reason that I’ve always been interested in manuscripts and

libraries, and of course in history. After I left the manuscripts division, I

worked for a period with the Newberry Library of Chicago, which was a very

2

fine experience, and then I spent approximately seven years as the command

historian of what was the United States Army Weapons Command. And then

I was a professor for about nine years, and I was also the chairman of the

history department at Augustana College, and so it’s from that background

that I came to the library in 1969 as the assistant director, and I became

director in the fall of 1971. And I might just tack onto that that Mr. Truman

died fourteen months after I became director, and I feel like I’ve been on a

merry-go-round ever since.

WILLIAMS: Who was the director before you were?

ZOBRIST: His name was Dr. Philip Brooks, and he had spent all of his career in the

National Archives. He had joined the National Archives in the early 1930s

when the archives was formed. And, of course you realize this is the second

presidential library, and it’s the first presidential library that really came into

existence under the Presidential Libraries Enactment, so this library really cut a

lot of new ground when it came into existence. And I also might say that the

library really led the way in a lot of innovative things, you know, setting the

pattern for what libraries were to be in the future.

WILLIAMS: How would you describe Dr. Brooks’s relationship with the Trumans?

ZOBRIST: It was not a very good relationship, and I don’t know all of the background of

it, but it was not a very good relationship. I recall that while I was at the

library that Dr. Brooks, and I don’t think I’m exaggerating, was just simply

terrorized when he knew that Margaret Truman Daniel was going to visit the

library.

WILLIAMS: So he did not have a good working relationship with any of the family?

3

ZOBRIST: No.

WILLIAMS: And you don’t really know why that was?

ZOBRIST: Well, if I could surmise about this . . . And then let me say that I think very

highly of Dr. Brooks. He is a very fine gentleman. He was very kind to me,

and I would give him great credit, as I have previously alluded to, for really

establishing the foundations of this library and doing a lot of pioneering things

in the whole presidential library realm. I sense that the problem is that Dr.

Brooks was too “GI,” if I may put it that way. In other words, he felt that he

was very, very strictly bound by government regulations, and when you’re

dealing with a president and a presidential family, you just don’t do it that way.

WILLIAMS: Would you describe yourself as a Truman scholar before you came to work

here?

ZOBRIST: No, but my background is in modern diplomatic relations, and the twentieth

century is my field. Although Truman was not really a specialty, certainly the

postwar period, diplomatically speaking, was very much my field, and I had

written articles in that area. I think also the background that I had as a

command historian and writing about the military history during that period,

that certainly I had no problems in, say, just moving over a little bit into the

Truman field.

WILLIAMS: How well did you know Harry Truman?

ZOBRIST: [chuckling] I never met him until I came here. Often when I identify myself,

certainly in the early years, I was asked that question because I think many

people feel that my position is a political plum or something like that. I was

selected off of a government register, and the story that was told to me by Dr.

4

Brooks himself is that when I had been selected by the National Archives, and

in fact I had been interviewed by Dr. Brooks, that Dr. Brooks took my

records down to Mr. Truman. Of course, you realize at that time that Mr.

Truman was no longer coming up to the library, and Dr. Brooks said that Mr.

Truman’s comment was: “If he’s good enough for the government, he’s good

enough for me.” And if I may, I’d like to tell the story of the first time that I

met him.

WILLIAMS: Please.

ZOBRIST: I came to the library in August of 1969, and when I knew that I had been

accepted for this job, and of course it had been a hectic year because not only

was I chairman of the department but I was associate dean and I was in

charge of the school’s summer programs that we were running abroad and all

kinds of things like that. But during the summer I did take the time to start

trying to get boned-up a little bit more on Mr. Truman, and when I dipped into

his memoirs in more detail, to my great surprise I realized that Mr. Truman’s

battery, when Battery D came back from France after the First World War,

came back on the very same ship that my father as a naval officer was

assigned to, and the ship is the U.S.S. Zeppelin. The ship was a German

intern liner. I inherited from my father, who had been deceased for a number

of years, many photographs from his career in the Navy. And believe it or

not, here was a great big, like about a two-and-a-half-foot by one-foot

photograph of the U.S.S. Zeppelin. So I took that along with me when Dr.

Brooks took me down to meet [Mr. Truman] for the first time.

And Mr. Truman, again if I may just divert for a moment, I was very

5

impressed in meeting Mr. Truman. I would have to say that having grown up,

and of course I had been in service during the Second World War, anyone

who had grown up hearing and knowing and reading about President

Roosevelt with his wonderful, eloquent speeches, his fireside chats, when you

would hear Harry Truman with his Midwestern sort of nasal twang, and how

he would occasionally stumble over words, I was not really all that impressed

with Mr. Truman as an individual. But, let me say that when I met him for the

first time I was greatly impressed.

I met him in the little side room, the study, and there I saw him with

stacks of books around him that I’m certain that he enjoyed reading very

much. But even though he was somewhat infirm, he stood up and he gave me

a very, very firm handshake. And what I remember very much are his eyes,

those sparkling blue eyes. And indeed, as soon as he shook my hand and

greeted me, I knew exactly what the term charisma meant. So I was very

much impressed with him at that first meeting. He was very cordial, very

polite.

I would say that I felt that he was very informed about the library, and

I might also add this. You know, in subsequent years, many people have

asked the question: “Well, what did Mr. Truman do in his retirement, and

what was he interested in?” And the answer is: He was very, very interested

in the library and what was going on at the library, new collections that we

were receiving, what were the scholars writing, and so forth and so on.

But to continue the story, after I had been introduced to him, I

presented him with this photograph of the U.S.S. Zeppelin, and he was very

6

pleased to receive it, but he returned it to me immediately and said, “You take

this back up to the library,” and so indeed that’s what I did. But it was even a

more interesting meeting for me because while Dr. Brooks and I were meeting

with him and chatting with him and talking about the library, through the back

door came Edgar Hinde, Sr., who was the postmaster of Independence. And

of course Edgar Hinde had been an old, old friend of Mr. Truman, and the

two of them had served overseas. And of course Mr. Hinde being such a

friend, he didn’t come in the front door. I mean, he just wandered in through

the kitchen door, and he was considered part of the family. Well, in any

event, Mr. Truman showed him this photograph of the U.S.S. Zeppelin, and

for a few moments it was most interesting to see the two men reminiscing

about their return voyage. And the one thing that I do remember is both of

them recounting what a, in their words, “rough rider” the ship was, and

apparently it was a rather wild journey when they came home.

WILLIAMS: How long were you there for that visit?

ZOBRIST: Oh, I would say perhaps twenty minutes to a half-hour.

WILLIAMS: And the whole visit was in the study?

ZOBRIST: Yes, that’s right. And I did not meet Mrs. . . . I don’t recall meeting Mrs.

Truman at that particular time.

WILLIAMS: Did you come in the front door or the back door?

ZOBRIST: Yes, we came in the front door. That’s right.

WILLIAMS: How many times did you visit with Mr. Truman before he died?

ZOBRIST: Well, I really have no count, but Dr. Brooks and I, while he was still at the

library, would go down, oh, I’d say every couple of months and have a chat

7

with him. I went down individually after Dr. Brooks retired, but only for a

very few times, and indeed when Mr. Truman’s health took a turn for the

worse, the visits were canceled.

The one experience or visit of his that I really do remember very

vividly is a visit that he and the family made to the library. And you see, he

died in 1972, and so this was the year before, in December of 1971. The

library had just completed a half-hour film, a, let’s say, general orientation film,

a film that described the decisions that were made during the Truman period.

Also it covered the ’48 campaign and a number of other related administration

events. But we had just received that film a few weeks before.

And I should really start at the beginning of the story, in that it was that

December that Margaret and Clifton and the boys came out, and the family, I

think, just had a very, very nice Christmas season. But Clifton Daniel called

me about the day before . . . We did this on . . . it must have been Christmas

Eve or the day before Christmas Eve. Clifton called me and said that Mr.

Truman would like to visit the library. And I said, “Fine.” Clifton said, “I

want you to arrange it so that we will do it after-hours”—that is, after five

o’clock—and he said, “just dismiss all of the staff that you can dispense with,”

which indeed I did. Of course, I did not tell the staff that the Trumans were

visiting after five o’clock, but they came up about a quarter after, twenty after,

and I was the only one here, plus the security people that we had. And I also

recall that Clifton said, “Don’t make it obvious, but you really ought to have a

wheelchair handy,” in case Mr. Truman would need one, and so I arranged

for that as well.

8

Well, they arrived and it was just really a rather dark, dreary, wintery

night. I don’t recall if there was snow on the ground, but it was just not a very

pleasant night. But they arrived and I . . . First of all, we had just received in

our collection one of the Lincoln limousines out of the presidential fleet. And

at this point in time it had not been restored, but we had it out in what was

then the garage of the building, which would be next door to where we are

sitting, and of course now completely changed. So I walked them out to the

garage for him to see the limousine, and he just enjoyed that very much. And

then we walked back into the library, we walked down the hallway, and I

took them into the auditorium, and although I don’t know much about rolling

films, I got to do all of the honors that night, and fortunately . . . They sat right

in the middle of the auditorium, the whole family. The boys did not come, by

the way, but Mrs. Truman did come, and I went up to the projection booth

and I pushed all of the right buttons and it happened, and it just worked

beautifully! And after I got the film rolling I came down and I sat behind the

Truman family, and I could just hear him chuckling and commenting. He just

thoroughly enjoyed the film. And after the film was completed, then we

walked through the rest of the museum, and then they left. And he did not . . .

He walked the whole way. And I think he just thoroughly enjoyed coming up

to the library because, to the best of my knowledge, he had not physically

been in the building since his health no longer permitted him to come up, and

that would have been 1966. And of course we’re talking about 1971. But it

was a delightful visit.

I might also add, while we’re talking about visits, that in preparing for

9

the annual board meeting—that is, of the Harry S. Truman Library Institute—

which we hold in . . . then we were holding it in March of the year, I went

down to the house and had a brief visit with him. Then I had another occasion

to go down and see him, if I remember correctly, in May of that year, ’72,

and of course that’s the year that he died in December. And I would have to

say that of all of the visits with him, that last visit in the spring of ’72, the year

he died, was the visit that I found him really the most alert and the most

articulate.

WILLIAMS: Were all of your visits in the study?

ZOBRIST: Yes.

WILLIAMS: On these visits, did you notice any changes really in the house, the way things

looked?

ZOBRIST: No. No, there were no changes. In fact, moving on a little bit, after Mr.

Truman’s death and when Mrs. Truman was alone, occasionally Margaret

would call me and tell me that her mother wanted to redo the kitchen or might

want to redo one of the other rooms in the house, and I very strongly

discouraged her from doing that, to say the very least. And so I would say

that the house as I saw it is just exactly the house that you have today.

One other thing I might add is that I think that sometimes when people

see the house today that they think that the park service has phonied it up, in

terms of the hall tree in the back hall there with Mr. Truman’s coat and cane

and hat hanging there. But I would say that even after Mr. Truman’s death

when I would visit the house, that’s exactly the way I would see it. And so,

you know, really nothing has been changed, and I can assure you that . . . I

10

would assure the public that you people are presenting the house very

accurately.

WILLIAMS: You said that Margaret told you that Mrs. Truman was interested in

redecorating?

ZOBRIST: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Do you think that was really Mrs. Truman’s wish, or was it maybe Margaret

speaking for her?

ZOBRIST: I would say it was Mrs. Truman, because as soon as I would discourage

Margaret . . . That’s the way I would read it, let’s put it that way.

WILLIAMS: So you think Mrs. Truman did have a genuine interest in sprucing the place up

a bit?

ZOBRIST: I think she did. That’s the way I would react to the conversations I had. You

know, along that line, and you may be asking me this later, but do let me say

that I think that even after Mr. Truman’s death that by that time that Mrs.

Truman, although I was not privy to the will at that time, but I’m certain that it

was the full intent of the family that the home go to the government.

One of the little sidelights that I would have to deal with from time to

time is . . . I can’t recall the gentleman’s name, but the person who did the

painting and took care of the home, let’s say the outside of the home, and I’m

certain I could find the name of this individual, and you may have even

interviewed him, but I recall him every once in a while either coming up to the

library or calling me and just saying, “Can’t we do something about the house?

The house is just falling apart!” And he would say, “I’m really almost literally

keeping the house together with baling wire and chewing gum.” And of

11

course you realize at that time that the government had no responsibility and

could expend no money for the care of the home, and I just had to bolster his

morale and tell him to do the best job he could.

And thinking about that period, and I’m moving ahead in the story,

you may have some questions you may want to come back to, but another

issue that I would . . . The library and I being the people on the scene, so to

speak, we were the ones that got the public comments and the public

complaints. Mrs. Truman sometimes would not get the grass cut in a timely

fashion, and I would get complaints about that as to why isn’t the government

taking care of this or that. And of course I would have to try to deal with that

diplomatically, too. But I think that we realize that Mrs. Truman was way up

in years, and I think we all realize the difficulty of getting responsible help to

do things, and Margaret was of course in New York throughout this whole

period.

Although, while I’m on that point, many times I would get comments

from the community about “Well, why doesn’t Margaret come out and spend

more time with her mother?” and “Why doesn’t she visit more often?” that

type of thing. I think many people felt that Margaret was neglecting her

mother. And what I would certainly point out here is that you have to

remember that Margaret has four sons. Margaret had a lot of family

responsibilities during this period. I know that for a fact that she spoke with

her mother on the telephone several times each week, so Margaret was

always totally in touch, and also she was in touch with the friends and the

neighbors who worked with Mrs. Truman.

12

WILLIAMS: When Mr. Truman was still alive and you would visit, who controlled the

schedule? Did you have to make appointments?

ZOBRIST: Well, yes. The way that it was handled is that we still had Rose Conway here

at the library, and as you know, she was the president’s longtime secretary, to

say the least. And really, when we would go down and see Mr. Truman, all

of the arrangements, the appointments, etcetera, etcetera, were made through

Rose. And indeed when we wanted letters signed by Mr. Truman or wanted

books autographed or anything like that—he was very good about that—it

was Rose who handled all of that.

WILLIAMS: We need to pause briefly.

[End #4135; Begin #4136]

ZOBRIST: Not at that time, but you realize that as long as Mr. Truman was living, his

presidential . . . whatever the term is, allowance, provided for her. And after

Mr. Truman died, the library took her on our staff, and she continued to

support Mrs. Truman. As you can imagine, over the period while the

Trumans were still living, there was still quite voluminous correspondence. I

got to know Miss Conway quite well, but I think that we all realize that she

was a very, very private person. She really dedicated her whole life to Mr.

Truman and to the Truman family, and as hard as we tried, we could never get

her to do an interview. And indeed even after her death she left very, very

few things of any significance, in terms of papers, mementos, or anything like

that. I would describe her as really one of those faceless, dedicated women,

totally devoted to Mr. Truman.

WILLIAMS: What were your dealings with the Secret Service while Mr. Truman was still

13

alive?

ZOBRIST: Well, that’s another interesting story. The Secret Service had already arrived

on the scene before I came, but . . . I’m telling you now both a story that has

been told to me, and of course I will also be speaking about firsthand

experience after I came to the library in 1969. Presidents did not receive

Secret Service protection, of course, until after the Kennedy assassination.

And I have been told that the first group of agents, I would imagine three or

four people that were sent out, that the Trumans just did not like them at all.

And I don’t even know the names of these individuals, but the Trumans were

never enthusiastic about the Secret Service. And of course you realize that

the city of Independence had provided protection for the president essentially

in terms of Mike Westwood. But to continue with the Secret Service, the

Trumans didn’t like the group that was sent out, and so they sent them back.

They went back to Washington. And then the Secret Service sent out another

group of Secret Servicemen, and I believe this group was headed by Paul

Burns. You know, I hadn’t expected to talk about some of these things, so I

don’t have perhaps a lot of these things at my fingertips. But I knew Paul, and

he was a very fine person with a very outgoing, optimistic sort of fun type of

personality, and so the Trumans accepted the second group that was sent out.

However, the Trumans would not permit them in the house. And I’m

telling you this because you asked the question, you know, “How did the

library relate to the Secret Service?” Well, what happened is that the Secret

Service was given a room at the library. In fact, the room that we gave them

was the room next to the garage, which is now my administrative secretary’s

14

office. And you realize at the time that the library administrative operation was

on the far side, which would be on the west side of the building. Then you

have the Truman Wing, the Truman Administrative Wing here, and of course

we’re sitting in the conference room, and then you’ll see next to the garage, to

the east of us, was the room where the Secret Service operated. And it was a

pretty bare-boned room, to say the very least, but what they had done is to

install television monitors. And so they had, I think, at least the state of the art

at that particular time, the 1960s. They had the state-of-the-art television, and

also they had all types of electrical as well as electronic devices for opening

and monitoring gates and doors and things like that. But what it meant, and

we just really kidded these guys a lot, they would spend most of the day up

here monitoring the television, and they, of course, with their cars they would

swing by the Truman home occasionally. And then these poor guys, winter or

summer, rain, shine, whatever, snow, they sat out in an automobile right on the

street during the night to watch the Truman home. And that was their life for a

number of years.

Let me divert for a moment, in that I think that a lot of times the public

really questions the need for this type of protection. But let me say that even

after all of those years Mr. Truman would still occasionally get an intimidating

or a threatening letter and kooky types of things. I can remember one, a

woman who would write Mr. Truman from California, and she claimed that

she had been secretly commissioned a five-star general, and she would sign

her letters as “Generalissimo . . .” I don’t recall the name that she used, but

she would send letters occasionally. You know, not to divert into this, but all

15

of these elements were checked out by the Secret Service. But in any event, I

can assure you that even after all of those years, this type of thing would go

on.

Well, let me get back to the Secret Service. The Secret Service, the

next phase that they went through is that they got a van, and so that made it a

little bit easier for them to operate and to monitor the home. But of course we

razzed the living daylights out of them, saying that, well, gee, they got a van so

that they could go fishing on weekends. However, the change really came

with the Secret Service in the protection that they could provide when they

were able to secure on a rental basis the home immediately across the street.

But again, you see, the Trumans would not tolerate them in the home. But at

least the Secret Service had a place where they could visually see the home,

and they could monitor it a lot easier, and they didn’t have to sit out in their

cars all night. It was quite a sophisticated operation. All of their monitors

were moved down there, and their whole operation was transferred down

there. And see, they had a big sort of front window in the home, and that’s

really where their operational desk was, and there was always an operator

sitting at that desk monitoring the front gate and the front door.

And I recall at that time when I . . . Well, at that time, my visits were

still . . . I guess you might say on a formal basis, in that I did not come in the

back door. But I would go to the front gate, and of course telephone

arrangements were made previously, and I would always wave and signal

over, and somebody would push the button and the buzzer would . . . you

would hear it and the gate would be opened.

16

But I guess just one last thing I would say, the Trumans, the whole

family, liked Paul Burns, and his people very much, and I think that it was a

good relationship. I would have to say though that I felt very sorry for Paul

Burns because I think it was sort of like your organization and like the military,

that you don’t want to get stuck in an assignment for the rest of your life, and I

think that Paul had the Truman assignment for, oh, seven to nine years,

something like that—in other words, far beyond his tour of duty—and I don’t

think that helped him career-wise. But on the other hand, he was the only

person that the Trumans would accept. Later, he switched with the man who

headed President Johnson’s security, and so there was eventually a turnover.

But I think that tells about the Secret Service.

I might mention one further thing that comes to my mind, and getting

us closer to the time of Mrs. Truman’s death. Toward the end, I’d say about

the last three years of Mrs. Truman’s life, there was a lot of turnover in Secret

Service staff. And I guess you can understand that, because Mrs. Truman

was no longer going out and so she didn’t need escorts or that type of thing,

and I’m certain that the Secret Service used this as sort of a, what,

introductory or indoctrination, that type of basic training for the young fellows

that were coming into the system.

WILLIAMS: Were you ever in the Secret Service house on Delaware?

ZOBRIST: Oh, yes, many times.

WILLIAMS: Why would you go into the command post?

ZOBRIST: Well, I would simply go down to visit the fellows [chuckling] from time to

time. But more than that, I think that you need to realize that there was a lot

17

of planning with reference to Mrs. Truman’s funeral, and how . . . You know,

we haven’t touched on that at all, but even before Mr. Truman died, going

back to that early period, I would have every single week two or three

meetings with the Army, with the Secret Service, with GSA, and my staff, in

terms of the planning for the funeral, as well as the funeral director.

WILLIAMS: When Mr. Truman visited the library, you said in the winter of ’71, I believe,

was the Secret Service with him then? Did they generally escort him?

ZOBRIST: No. No, they didn’t. I don’t recall any Secret Service being there at all,

although they probably were monitoring the visit. But no, it was just strictly

the family.

WILLIAMS: When did you first meet Bess Truman?

ZOBRIST: I met her in the subsequent visits down to the house.

WILLIAMS: And how would you describe her reception to you?

ZOBRIST: Oh, very cordial. I liked Mrs. Truman very, very much. She had an excellent

sense of humor, she was easy to talk with, as Mr. Truman was, and even in

subsequent years when I would telephone her, when she was no longer really

that active and getting out, I always had just really very good telephone

conversations with her because I felt that she had such a nice, friendly

disposition.

WILLIAMS: At the time of Mr. Truman’s death, were you in the home afterwards, around

the time of the funeral?

ZOBRIST: No, I don’t recall that I was, not during that period, not in December or

January of that . . .

WILLIAMS: You didn’t accompany any of the dignitaries to the house?

18

ZOBRIST: No.

MICHAEL SHAVER: To back-pedal a little bit, you talked about all the planning that had

gone into this for a good number of years.

ZOBRIST: And we can talk the next hour on that one!

SHAVER: I think you’re the only library director that’s had the honor or horror of having

to plan a state funeral twice. As I remember you saying at one point in time,

and I’ve read in other places, there was a rather elaborate plan in the works.

ZOBRIST: Yes.

SHAVER: There were weekly meetings. In fact, Dr. Graham almost had the scenario of

how things would probably happen with Mr. Truman. When did you have to

essentially tear up the notebook and start all over again?

ZOBRIST: Oh! [chuckling] Can we close this part of the tape? [laughter] You know, I

haven’t thought about this for a long time. You know, really, to pick up on

what you’re saying, from where I sat, I sort of felt like I was in the center of

this storm that was swirling all around me, so to speak. In my observation, the

state funeral for President Truman was, in essence, run by the Army. And the

person there, and indeed you might want to interview him, was Paul Miller,

Colonel Paul Miller. You know, I would say that I was literally thrown into

this as soon as I came to the library.

And of course I will tell the story that others have probably told, of

how President Truman was finally gingerly approached by the military and

some of his old friends, and really it was Tom Evans who was the key to the

situation, and told that, “Well, you really ought to be making plans.” And as I

understand it, they finally did have one large meeting in his office, and it was at

19

that meeting that he told them where he wanted to be buried, and apparently

he pointed right out to the courtyard where he wanted to be buried. They

described, I guess in some detail, what a state funeral would be, and they did

it in a very somber fashion, very seriously, a very serious fashion. And Mr.

Truman supposedly cracked up the whole group by making a comment to the

effect that he was so impressed with all of the planning that he wished he could

be there.

But getting on with the story where I . . . See, the title of the whole

plan is called the “O Plan Missouri.” The “O Plan Missouri” was a book the

size of a Sears and Roebuck catalogue, and it was written in that much detail.

I was brought into this as soon as I came to the library, and to repeat what I

had said before, every single week there were two or three meetings. And I

would have to say that, knowing my background that I’ve already described, I

absolutely had no training in this type of thing at all. And quite frankly, there

was a time after several months that I just really became very depressed from

working with all of this, because it just went on and on and on. And

everything was planned in such extreme detail, and plans were reviewed, and

then re-reviewed. I guess I should have stated previously that the Army has a

special unit at Fort . . . I can’t think of it, in Washington—it’ll come to me—

but it was then headed by Colonel Miller. And that’s all this unit did was plan

state funerals. But to continue, Paul Miller would come up periodically and

re-review plans. I would have to say that we were all in touch with each other

continually. For the first time in my life, I had to carry in my billfold telephone

numbers of all of these people. When Mr. Truman’s health really started

20

deteriorating, if I went out of town, if I was beyond a telephone call, I had to

inform Colonel Miller. In other words, we were all very closely in touch with

each other.

Also, I think you need to realize that Mr. Truman’s health started

deteriorating, and then it went on for months. And of course, dealing with the

Army, with GSA, as well as the Secret Service, you would have new officers

and new individuals coming into the picture and older ones retiring and leaving,

and so it was a continual process of reviewing and updating.

WILLIAMS: How much input did Mrs. Truman and Margaret Truman Daniel have in the

funeral plans?

ZOBRIST: Very little at the outset. The instructions that Mr. Truman gave was that they

were not to be bothered or really to be consulted about this. I just have the

feeling that this was something that he just did not want to burden them with.

And so that’s the reason that things were so hectic in the very last days,

because, you see, the family in essence had not been privy to a lot of this stuff.

And then when we got to the point, there was a lot of changing. In fact, I

with some of my key staff . . . When Mr. Truman . . . when his death was

imminent, we were working complete weekends, updating lists and things like

that.

WILLIAMS: How did you find out about his death?

ZOBRIST: [chuckling] It’s interesting, and of course somewhat disappointing, if I can put

it that way.

WILLIAMS: Let me guess, a reporter called you. [chuckling]

ZOBRIST: No! [chuckling] Here I had been following everything so closely and had

21

been in telephone touch with everyone, and at that time I lived in

Independence, about twelve or fifteen minutes away from work, and I got in

the car that morning and the news came over the radio that morning, and so I

heard it on the radio driving to the library. But of course we knew that it was

imminent, but to me it was just very much of an anticlimax.

WILLIAMS: So once he had died, the family did make modifications to the plans?

ZOBRIST: They did, but this is something that I really cannot speak directly to because

you realize it’s the senior service, the Army’s responsibility, and so it was

Colonel Miller who really at that point in time dealt directly with the family.

And then after Colonel Miller had briefed the family on what the scenario

would be, it’s at that time that I began receiving direct instructions from

Margaret.

WILLIAMS: Let’s get back to more happier memories.

ZOBRIST: Yeah. [chuckling] But do let me say this. I know that this is not really what

you came up to tape me about, and that is a total story that may not fall within

your purview, but I could speak at least another hour on this subject, and we

have good resources in our holdings. I would hope someday that someone

would do a thesis on this, because it’s an interesting subject, and it should be

dealt with. But let’s move on.

SHAVER: I might take the opportunity to do that again sometime.

ZOBRIST: If you want to spend another whole morning, we’ll do that, okay? [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: When you visited Mr. Truman in the home, did he or anyone else ever offer

you refreshments?

ZOBRIST: No, these were always very businesslike meetings. And in fact, I might add

22

that by the time I came to the library I was not aware that the Trumans really

did any entertaining or anything of that type.

WILLIAMS: When it was just Mrs. Truman then in the house, how often did you visit her?

ZOBRIST: That was much more infrequently, basically because she did not have the

strong interest that Mr. Truman had. I might add that Margaret encouraged

me to talk with her and call her periodically, and I think more to want . . .

change her mind, I guess, and to let her know what was going on, to a certain

extent. Because Mrs. Truman really did not get out of the house very much.

Although, you know, let me say that in the years immediately after President

Truman’s death she did get out, I think, much more so in those years. Every

once in a while I would hear someone say, “Oh, I saw her at the grocery

store” and around town. I can remember my wife saying, “Oh, I saw Mrs.

Truman leaving the beauty shop this morning,” that type of thing. I don’t

consider myself any expert at all on what Mrs. Truman was doing during that

period, but I think you need to talk with some of her lady friends and the

people that lived down there, but it’s my understanding that she led a very

normal, active life and was very interested in what was going on in the

community.

WILLIAMS: Did she ever come up here to the library?

ZOBRIST: Yes, she surprised me. she came up one day, one afternoon. It was in the

summer. I can’t even tell you what year. But I was surprised by that visit.

She came up and she wanted to give me something, I don’t recall what it was.

She left the car out in the circle of the administrative entrance, and I took

what she was giving me, and I said, “Well, won’t you come in?” And I

23

brought her into my office, which is not my present office, but the office over

on the outside of the building. And, uh, we had a very pleasant, you know,

cordial conversation, but the thing that surprised me was that Mrs. Truman

said, you know, I have never been in this office before.” So I have the feeling

that . . .

[End #4136; Begin #4137]

WILLIAMS: When you visited Mrs. Truman in the home, where were your visits?

ZOBRIST: Oh, always in the study. I will take that back, there was one occasion that I

do recall where we sat in . . . I don’t really know what you call these rooms,

the room to the right as you come in.

WILLIAMS: The big living room.

ZOBRIST: Yeah, the big living room.

WILLIAMS: And did you have staff members going down to the home to see Mrs.

Truman?

ZOBRIST: No, not until . . . No, the answer is definitely not until . . . You know, she fell

in the early summer of ’81. And here let me tell you the story of our

involvement, really, with the home. It’s at that time when Margaret visited the

home, and of course visited her mother, and of course she would have been

out for our annual board meeting as well because by that time we were

holding the board meetings in May, that Margaret expressed a concern with

the home, that she had noted something was missing from the home. And I

don’t really even recall what it was. I think it was a small clock or something

like that. And I think that she realized that her mother was having more

difficulties, and she also realized that there were nurses attending Mrs. Truman

24

and also a continual stream of Secret Service in and out of the house, and it’s

at that time that she asked me to start inventorying the home very discreetly.

And that was where my staff members entered into it. I say staff members,

there were only three or four individuals, and these were longtime staff

members that I had great faith in.

WILLIAMS: Before we get deeply involved in the inventory, I have a couple more

questions.

ZOBRIST: Sure, go ahead.

WILLIAMS: Did Mrs. Truman have secretarial help at all?

ZOBRIST: Only Rose.

WILLIAMS: How long did that last?

ZOBRIST: Well, it lasted . . . I would have to say I draw a blank on that. I don’t

honestly remember. It lasted as long as Mrs. Truman needed secretarial help.

Let me add something into that, in that right after Mr. Truman’s death . . .

You see, at that time Rose would still go down to the house and . . . [tape

turned off] Okay, well, let me say that when Mr. Truman was living, and of

course after his death, in the early years after his death, Rose continued in her

office here, and she would go down to the home. But later on when

correspondence started dropping off, and indeed Rose was having some

health problems herself, the Secret Service would bring things back and forth.

I guess you might say it doesn’t fall officially under their duties and

responsibilities, but this was a rather, what, uninspiring type of assignment, for

openers, so indeed these Secret Service fellows . . . I mean they just enjoyed

getting out and doing anything they could to help Mrs. Truman and to help the

25

library as well.

WILLIAMS: On your visits with Mrs. Truman, did you ever take her gifts or anything?

ZOBRIST: Not that I recall. I would take down occasionally our newsletter. It would be

official things that I would take her.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever take her books from the White House Historical Association on

first ladies and the White House?

ZOBRIST: I don’t recall. I mean, if they went down, they would be sent down. I

wouldn’t do it myself.

WILLIAMS: We have several copies of these books, and we were wondering where they

might have come from, from that period.

ZOBRIST: You know, again let me make another comment that I enjoyed Mrs. Truman

very much. She was a wonderful person. I had excellent—when I say “I,”

the library and I had excellent relations with her. I think that you have to

remember that as I came into this job, and I’m not kidding when I said I feel

like I have been on a merry-go-round, see, I had only been director fourteen

months before Mr. Truman died, and I think that you need to realize that there

were just massive administrative and library responsibilities that I had, in terms

of processing new collections that we were receiving, you know, to say

nothing of the subsequent reception of the Truman papers. I was, boy, up to

my ears in library responsibilities. I had personnel issues and problems that I

had to deal with. I was establishing new administrative policies and

procedures and attempting to give the library newer direction. Just to give you

one example, the library had never embarked on an acquisitions program for

papers, and so this was a major undertaking. But this just gives you one

26

example of many, I guess we might say, initiatives and programs that I

embarked on. For example, I wanted us to publish a more sophisticated and

polished quarterly publication, and so, really, when you ask me these

questions, you know, the bouncing ball that I was following was the

administration of the library, and indeed Mrs. Truman was far from the center

of my focus, to say the least.

WILLIAMS: You let on earlier that later on you came through the back door when you

visited. Is that correct?

ZOBRIST: That’s true, but this was at the time after we started inventorying, and

Margaret had at that time given me and my selected individuals really

complete access to the home.

WILLIAMS: One more thing before the inventory, when you visited Mrs. Truman, what did

you visit about?

ZOBRIST: Well, that’s interesting, I’ve been asked that question many times, and people

expect me to give the answer that we talked about the weighty issues of the

world. And the answer is we did not talk about the weighty issues of the

world. It was more pleasurable conversation in which we talked about the

town. We didn’t talk about political issues, but we talked about the town,

what was going on at the library, the weather, that type of thing. In fact, Mrs.

Truman was very, I think, discreet in the conversations that she had with me.

Again, I may be presumptuous in making an observation like this, but I think

you need to remember that my predecessor did not have good relations with

the family. I have always felt that my job was to build bridges with people,

and I felt that my greater mission, if I may put it that way, was to get people

27

talking to each other. I wanted people to understand what we were doing at

the library, and I wanted the Trumans to realize that the library was here to not

only help enhance the image of Mr. Truman but basically to tell the story of his

administration and tell the story of his life, and so I purposely avoided

controversial issues. I can’t really stress this enough, because in my estimation

there was a lot of changing of opinions over the period from 1969 when I

came to the library till the time in ’71 when I became director, until ’72, until

you get past the death of Mr. Truman into Mrs. Truman’s period where she is

living at the home, where Margaret at that point in time perceived me and the

government, in a sense, as not being the enemies but . . . I know this is

somewhat of an overstatement, but perceived me and the library in a more

positive light in what we could do.

WILLIAMS: Why do you think Margaret’s opinion changed?

ZOBRIST: Well, again I don’t wish to take undue credit or more credit than I should. It’s

a question I don’t think that I can totally answer. I think that certainly part of

it, in my estimation, would be the positive image that the library and I tried to

project. I think that nothing is that simple. I think it’s also a matter of

Margaret perceiving that we did have a role to play in the memory of her

father, and also in the transfer of the remaining papers and the transfer of the

home to the government.

WILLIAMS: And at this time was she a member of the institute?

ZOBRIST: Oh, yes. In fact, President Truman had been the honorary . . . was the

founder and the honorary president of the institute, and when Mr. Truman

died, the board unanimously elected her to the board as an honorary member.

28

And she continues to be active in the organization.

WILLIAMS: Well, before Mr. Truman died, did you have any official contact with the

National Park Service?

ZOBRIST: No. [chuckling] Well, no, let me back up on that. The answer is yes, I did.

Really, it was a very delightful experience, and this is my acquaintance with

Connelly—I can’t even think of his first name.

SHAVER: Ernest.

ZOBRIST: Ernest. That’s right, Ernest Connelly. In that the park service apparently had

always wanted to recognize the Truman home. When the Trumans were first

approached, the Trumans declined the recognition. And it was not until some

years later that the park service, and namely Ernest Connelly, resurfaced the

issue, and if I remember correctly, this was around the time of the bicentennial.

But Mr. Truman was gone by that time. No, he was still living. The park

service exchanged correspondence . . . Okay, it’s all coming back to me

now. Yeah, in fact this was even before I became director. The park service

resurfaced this, it must have been in 1970 or early 1971, and at that time the

Trumans stated that they were willing to have the park service recognize the

home. But if I remember correctly, there were a couple of stipulations, and

one would be that there would be no marker, and if I remember correctly, I

think that there would be no particular publicity attached to the recognition.

So, in other words, you see, even when the Trumans finally did say yes, it was

in a very low-key fashion, to say the least.

But one other thing I do remember . . . You know, I wish I had

known you were going to ask me about some of these things. I would have

29

surfaced some of these names. The park service sent out a couple of their

historians, one a very distinguished gentleman, now retired. Can you give me

any names?

SHAVER: I have that study, but I can’t recall who wrote it.

ZOBRIST: But in any event, we gave these two fellows . . . I got such a kick out of this.

We gave them an office down the hall in the administrative wing, and that’s

where they operated out of for a number of weeks. But this probably was the

most unorthodox recognition that the park service handed out, to the best of

my knowledge, in that they were never allowed to go into the home, and so

everything was done, you know, remote control. But they spent many days

surveying the district. And also I think that this is quite different because here

you have a recognition that was initiated by the park service rather than

coming up from down under, so to speak, as most of the recognitions are

made. But I can recall visiting with these people, and they did a very thorough

study. I was interested . . . To me, you know, I had not been at the library all

that long, and let me say I am certainly not versed in how the park service

operates and how it sets out districts, but I was most interested in the district

that they did cut out, so to speak. And as I understand it, there was a small

version and a large version, and if I remember correctly, the final selection was

the smaller version of the area that had been marked out. And that was in the

early ’70s, and I would have to say . . . I mean, this is another long,

complicated story that we could spend a whole morning talking about, but

along with the Jackson County Historical Society—and the person that I

would single out there specifically would be Hazel Graham—Hazel Graham

30

and I and some other historically-minded individuals in the community

persuaded our mayor to establish the heritage commission, and that’s how that

whole thing was launched.

WILLIAMS: Did you have any other contact with the park service before Mrs. Truman’s

death?

ZOBRIST: No.

WILLIAMS: Did you know the provisions of Mrs. Truman’s will before she died?

ZOBRIST: Yes.

WILLIAMS: How long before that did you know she was giving the house to the Archivist

of the United States?

ZOBRIST: It was really a matter of years. And let’s talk about that point.

WILLIAMS: So she wanted you to know?

ZOBRIST: Yeah, she did. And let me say that I wasn’t all that happy about it at the time,

and my people in Washington weren’t all that happy about it at the time,

basically because although there are a couple of exceptions in our system, we

are not into the preservation business and into taking care of historical homes.

And indeed I did express to the lawyer more than once, and quite strongly,

that the will should be rewritten so that the home should go to the park

service. And I can tell you that apparently . . . You know, I did not speak

with Mrs. Truman about this directly at all. I did not feel that I had that . . . I

did not feel comfortable in bringing up a subject that delicate with her, but I

know that the idea was conveyed to her. But the point that I would make,

and the interpretation that came back to me was that Mrs. Truman was

comfortable with the National Archives and with the way that we had

31

administered the library, and that was the way she wanted it.

WILLIAMS: Was the attorney Arthur Mag?

ZOBRIST: Yes, and then subsequently Don Chisholm.

SHAVER: Did Mr. Mag come and visit you one afternoon, or call you, or did Mrs.

Truman convey this, or Margaret convey this to you? How did you first find

out?

ZOBRIST: No, Mag just simply sent it to me at the library. I would visit Mr. Mag

periodically at his office, but I guess when I look back on those days, the . .

. Well, Mr. Mag was cut out of a different cloth, I guess you might say, a very

distinguished gentleman of an older generation. And although I never had any

difficulties with Mr. Mag, he was always very pleasant with me, when Mr.

Mag would speak it was like God speaking, so to speak. [chuckling] And so

even though I would protest, it would always come back: “Well, this is the

way Mrs. Truman wants it.”

WILLIAMS: Did you ever try to talk to Mrs. Daniel about this provision?

ZOBRIST: No, because my relations with Margaret, I would say, were such that again

this was an issue that I didn’t feel comfortable in raising with her. Let me add

a comment to that, in that Margaret was, over the years in this period, not the

easiest person to deal with. And I know that she had a lot of other things on

her mind, including the illness of her mother. There were other issues from the

viewpoint of my organization, in terms of papers and other things that were

really a higher priority with me in dealing and in negotiating with her. And if

you prioritize all of these things, I guess I would just really have to say that at

that point in time the matter of the will was not that high on the priority list.

32

WILLIAMS: Would you have agreed to use your employees to do the inventory if you had

not known that the house was being left to the archivist?

ZOBRIST: Well, I think the answer would be no without the approval of my superiors,

because I would not be permitted to expend government money and

government staff to do anything like that. But we knew that the material was

coming [with] the house, and just to add to that, this was a period before the

park service really had been brought into it. Just let me lay out a couple of

things here. I think you know that even after Mrs. Truman’s death there was

still a considerable amount of time that lapsed until the house was transferred

to the park service. And I fault my superiors in Washington, because on their

end they should have been talking to the park service and informing them

what was going down out here while I out here was trying to talk with the

lawyer, and the simple matter is that they were not. And indeed, my end of

the government did not move. My superior did not even move on this. It’s

my understanding my superior, who was the, now deceased, assistant archivist

for presidential libraries, did not even inform the archivist, his boss, of this.

So, in other words, my people in Washington, although I was informing my

boss, it was not getting passed on to his boss, and the big boss was not talking

to the people over in the park service. And so we were at pretty much of an

impasse.

SHAVER: When did things begin to move in Washington, at least on your side?

ZOBRIST: Not until after Mrs. Truman’s death.

SHAVER: Did they move in a timely manner at that time?

ZOBRIST: In my estimation, no. And that is the reason that I was hung with certain

33

responsibilities during that interim period, and it’s the reason that the

government had to pick up the tab for that private guard service, which I felt

was an expenditure that never really had to be incurred. But you have to

realize that not only you had this period up until Mrs. Truman’s death where

we are inventorying as quickly and as intensively as we can, but then, you see,

after her death then you’ve got this period where we’re all sort of living in this

halfway world. In fact, one of the brightest days of my life is when I saw . . .

not Norm Reigle, but the young man who came out . . . Tom?

SHAVER: Richter.

ZOBRIST: Tom Richter. When I saw Tom Richter come in uniform, boy, I felt like the

Marines or the cavalry had arrived! [laughter]

WILLIAMS: So, in your view, if the preparations had been made, the groundwork had

been laid, the home could have been transferred much more quickly after Mrs.

Truman’s death?

ZOBRIST: Yes, absolutely. There is no question about it at all. In fact, I had hoped and

felt that that’s the way that it would be done, but there were massive delays in

Washington. And indeed, getting back to the inventory, this is the reason that

I wanted to inventory—and I would also use the words “and secure”—the

items in the house there as quickly and as efficiently and as thoroughly as we

could, because I figured that when Mrs. Truman died that the estate and the

home would just be locked up and that would be it. So we worked very

feverishly, especially in the days when Mrs. Truman was deteriorating very,

very quickly. Do you want to talk about the inventory?

WILLIAMS: Yes.

34

ZOBRIST: I know that you’re interviewing my people who did the inventory, and so you

have to realize that I’m speaking more as an administrator sitting away from

the scene, and of course I would go down to the home periodically to see

what was going on and would give instructions as to how things should be

done. But the way it started out, as I remember it, is we were just going to do

this inventory, you know, somewhat leisurely, and to do a very thorough job

of it.

WILLIAMS: Excuse me, we need to pause.

[End #4137; Begin #4138]

ZOBRIST: Okay, well, I was going to say that when we started the inventory, I felt that

we would just do it on a room-by-room basis and do it somewhat leisurely.

But then the two primary people that were working at the house would be

Pat, her name then was Pat Kerr, and Liz Safly, people I have the highest

regard for, but they began to realize and I began to realize that, my God, the

house down there is sort of like Grand Central Station, what I alluded to

earlier, in that there were a constant series of nurses coming through and

taking care of Mrs. Truman, and then there was the young men, the Secret

Service people coming in and out.

The one vivid memory that I have is one day, it was either Liz or Pat,

one of them told me that . . . She asked me if I remembered the ashtray that

J. Edgar Hoover had given to Mr. Truman. You know, it’s the ashtray that

has Mr. Truman’s thumbprint in it. And she said, “You know, that’s missing.”

I mean, we almost had a stroke! A couple of days later they told me that

they had found this ashtray, and the ashtray was out in the kitchen and one of

35

the nurses was using it. And we’re about having a stroke because we would

consider this as a prime artifact, to say the very least. So it’s at that time when

this was happening, and we were beginning to realize the situation that we

intensified our effort very much, and then we . . . I told my people, I said,

“Loose things like that and small things that could disappear very easily, let’s

secure them and bring them to the library.” And so it’s my remembrance that

a lot of these things were brought up to the library at that time just simply and

basically for security because of the amount of people going in and out of the

house. And of course, in the late period of Mrs. Truman’s illness, I just think

that she just didn’t even realize what was going on around her. And I can

recall that the nurses occasionally would move her from room to room, and

although we were doing this inventory fully at the instructions of Mrs. Daniel, I

think I can recall them saying that Mrs. Truman didn’t even recognize them.

So I tell this story simply to reemphasize that the situation was, in my

estimation, a very risky situation in terms of what was in the home.

WILLIAMS: Was it your original intent to remove things from the home?

ZOBRIST: No.

WILLIAMS: That came along later?

ZOBRIST: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Did you keep Margaret apprised of the situation?

ZOBRIST: Yes.

WILLIAMS: How did you do that?

ZOBRIST: I would phone her. I can recall phoning her more than once and saying that

we were removing . . . and I would tell her what I was removing. And also

36

we kept inventories of the things that we removed. I think you need to talk

with Pat and Liz about this, because they can remember this undoubtedly in

more detail than I can, but you’re talking to an old Army type, so to speak,

and I wanted a piece of paper on everything, so that the government, and

certainly the library, could never be accused of taking things that should not be

taken.

But let me continue on and say that . . . a couple of other aspects. I

really can’t go into more detail than I have, because in my position I was

simply giving instructions. But things were removed basically for security

purposes. Things were also removed, for example, the letters, Mr. Truman’s

letters, basically because they were intended to come to the library anyway.

WILLIAMS: How did you know that?

ZOBRIST: Because that was in the will, in his will.

SHAVER: He had released all of his personal papers in the will. Is that how you recall it?

ZOBRIST: Yeah, and then we removed things that were . . . I guess the word I would

use, endangered. And I’m thinking of things that we felt were at risk. For

example, in the basement. And my God, you know, the basement was an

absolute disaster in terms of there was water seeping through the basement.

In fact, I can remember very vividly giving them instructions: “Don’t ever

stand in a pool of water and turn on a light switch in that basement or you’ve

had it!” I mean, really, I felt that it was a high-risk situation there, and I defer

to them. They can describe this, I’m certain, in a much better fashion than I

can.

And then the other high-risk area was the attic. Not only do you have

37

an unheated attic with great extremes of heat and cold, but there were even . .

. what was it, a raccoon or an opossum, whatever it was had gotten loose

upstairs there and had damaged certain things? And so the things that we felt

were of value, those items were removed as well. But the way that I look at it

is that it was more or less of, you might say, a rescue operation.

You know, one other thing that I remember during this period, we

took photographs of all of the rooms. And I know that these photographs

were passed on to the park service because it was my feeling that this would

certainly be the best indication of what was there, what had been there, and

where it was positioned.

WILLIAMS: Well, Pat Kerr showed us photographs that she took with her own camera. Is

that what you’re talking about?

ZOBRIST: Yeah, that’s right.

WILLIAMS: Did Margaret seem interested in the things you were finding or the progress of

the inventory?

ZOBRIST: You know, let me interrupt here and ask a question. You know, I’m telling

you guys exactly the way it is. Will I get a chance to read this thing?

WILLIAMS: Yes.

ZOBRIST: Okay, because I may want to, what, soften some of my statements here. But

I’ve always found Margaret not to be interested in the things of the house—

very much at all, not interested at all. Certain things, jewelry, certain things of

that type she brought up and she asked me to hold here in our vaults. But

another comment that I would make, and this is a true comment, if you’ve

worked with Margaret, she many times would shoot from the hip. And I can

38

just hear her saying, “Oh, Ben, throw that away! Get rid of it!” And indeed I

would have to say that I did not obey her instructions, and indeed let me say

that if I had carried out a lot of her instructions, I mean, our collection of what

we have and what you have down there at the house would be a lot thinner

than it is right now.

But let me also say that, in deference to Margaret, I think you need to

realize that this was a very trying period for her. I’ve lived through periods of

my life like this. You know, you get very impatient, and there are things you

just don’t want to be reminded of. There are memories that you would just as

soon forget, you know, things of that nature. But she was very liberal in telling

me, “Ben, get rid of it.”

But to move on, we did not dispose of anything. The only thing that I

can think of that we actually did dispose of, and I did this, what, very

discreetly, and I guess you might say with a grain of salt, in that she asked us

to get rid of a lot of her mother’s clothing. You know, all she would say is,

“Ben, get rid of it!” And then I got the problem of, well, how do you get rid

of it? The way we handled that, to the best of my memory, is that my staff,

being knowledgeable with reference to clothing, really just picked out the

worst dresses and the ones that really would never be used for exhibit

purposes—you know, her everyday dress, that type of thing—and these were

the dresses that we disposed of. It was sort of funny how my gang did it, and

you can ask them about it, but as I understand it, we wanted to be careful that

no one could ever say, “Oh, I bought a Bess Truman dress at the Salvation

Army,” or something like that. So my gang divided the clothing into groups,

39

and they dropped it off at a number of places like the Salvation Army. That’s

my understanding.

But again though, I’ve enjoyed working with the family, but perhaps I

had a little more perspective, if I may put it that way, realizing that my mission,

the library’s mission, was to save things for posterity. And as a result, I simply

did not carry out Margaret’s wishes.

WILLIAMS: You mentioned the family. Did you have any other contact with other family

members?

ZOBRIST: Yes, but in a minimal way. Going back, I’m afraid you’re going to get an

awfully scrambled tape because I’m bouncing back and forth here

chronologically. One of the first things that I did when Margaret asked me to

do the inventory was that I personally visited Bess’s sister-in-law May

Wallace, and I visited Sue Gentry, and I told them what we were about to do.

And of course I also visited Mrs. Haukenberry. That’s another whole story

by itself. You come back and interview me on that one when you get the

Haukenberry house.

WILLIAMS: Which may be soon.

ZOBRIST: Well, I’m delighted to hear that. And of course the minister.

WILLIAMS: Reverend Melton.

ZOBRIST: No, not Melton.

SHAVER: Reverend Hart.

WILLIAMS: Hart, the Episcopalian.

ZOBRIST: Yeah, the Episcopalian, yeah. Melton really never played much of a role in

any of this, to the best of my knowledge. But these were people that . . . It

40

was a very delicate situation, and I didn’t want to see in the newspaper:

“Truman Library staff inventorying Truman home in preparation for Mrs.

Truman’s death,” you know, something like that. And so this is the reason

that I visited a number of people and asked them to keep our confidence, but

I wanted them to know what was going on.

WILLIAMS: What happened to the objects and material that was removed from the home

once it got—

ZOBRIST: They were brought up here.

WILLIAMS: And what happened to them here?

ZOBRIST: We stored them in a room, I guess a couple of rooms, and the rooms were

secured, and only, what, approved people could work with it. I attempted,

and I think my staff . . . I shouldn’t say “I think my staff . . .” We attempted

to keep all this material as secure as we could. We did, as I understand it,

some preliminary, simple preservation type of work, if we could do it without

spending a lot of time, and then the thing that I was a real bug on was an

inventory.

WILLIAMS: So you kept an inventory of things as they came in?

ZOBRIST: Yes. My memory is somewhat hazy on that. You might want to ask Pat or

Liz about this, but the way I remember it is that we would spend a number of

days down at the house, and then we would spend a number of days up here

inventorying. However, I would say that when we got down toward the end

when Mrs. Truman was just really terminally ill—I mean, it was very, very

hectic—and I feel that it was somewhat of a problem to keep on course, so to

speak. But we did the best we could. And then I think you also have to

41

remember, and not to belabor you with my problems, I mean, this whole

operation in essence just came out of my hide, because it meant I was

diverting people from other responsibilities at the library to do this. And

indeed, if I had had more staff, and I guess I would have to say more

understanding from my people in Washington, this could have been done in a

much more efficient way. But in retrospect, though, although it was a very

hectic period for all of us, it was in many respects an emotional period that we

were going through. In retrospect, when I look at where we are today in

1990, I think my gang really did an outstanding job, and I would repeat myself

in saying that you wouldn’t have the home you have there today if it were not

for all of the anguish and gyrations and manipulations, and etcetera etcetera,

that we went through during that period.

SHAVER: Your superiors in Washington, was there any reluctance on their part to see

this take place?

WILLIAMS: Did you inform them that you were doing it?

ZOBRIST: Oh, yes. Yes. No, I wouldn’t say that there was any reluctance on their part

as far as the inventory. But I would have to say that I was yelling for more

help—personnel—all the time, and they were not listening to me. Of course,

they probably had other problems perhaps that they figured were bigger than

mine, but from my point of view this was a real strain on the staff. But really,

where I fault my people in Washington was in the transfer of the home, and

here is where I felt that they were definitely not responsive in carrying that

thing through in a timely and efficient way.

SHAVER: That’s interesting. Our folklore always has the paper put on somebody’s

42

desk in the Interior Department. I never felt like GSA had been—

ZOBRIST: Well, I think that if you check it out . . . No, let me say that I’ve heard that,

too, and I think that there was some delay and reluctance over in your end of

the government, but I’m talking about the delay that I saw in getting it over on

somebody’s desk over in the park service.

WILLIAMS: We usually blame the Secretary of the Interior. [chuckling] He at that time

was not a very . . .

SHAVER: Ike Skelton had no problem in blaming him.

ZOBRIST: Well, let me also add that when it got to that point, I would certainly speak

very highly of Ike Skelton and the role that he played. Ike has been a good

friend of the library, and I know that he knows Margaret personally, and

Margaret feels comfortable in speaking with him directly, so Ike can take

credit for what transpired as well.

SHAVER: Did you have any contact with Senator Eagleton or Mr. Skelton about this

issue? Did their staffs contact you?

ZOBRIST: No, not really. I did not. In my end of the government, and at least in those

days, and I will not give you a history of the National Archives, but I was

discouraged very, very much from speaking to any political individual.

I guess I would need to add one further statement to that, and this is

another whole story all by itself. My organization was going through major

organizational changes, and my organization was having tremendous problems

with General Services Administration, of which we were a part. And it’s

during this whole period, all of these years, that my organization was fighting

for independence. As you know, we’re now an independent agency. I don’t

43

want to get you into a lot of detail on that story, but I think that . . . Again

going back to what I have stated earlier, you have to remember that I had a

big library here with a lot of problems and new programs that I was operating

at the same time that a lot of this . . . the home was unfolding.

SHAVER: Viewed in that perspective, we can certainly understand. [chuckling] Did you

have much contact with the estate or the representatives of the estate during

this period, Mr. Chisholm or any representatives of that?

ZOBRIST: Oh, of the estate? Oh, yes, I had a lot of contact with Don Chisholm. You

see, by that time Arthur Mag had died. Yes, I have very, very high regard for

Don Chisholm, both as a lawyer and as an individual. He worked very closely

with the library, and in many respects I feel that he eased the way for us. I

would add, also, I think he represented his client, the Truman family, very