Last updated: February 6, 2025

Article

Don’t Tread on the ADA: A Rally and March to the US Supreme Court in 1999

By Ellie Kaplan/NPS Park History Program

On May 12, 1999, some four thousand people rallied in Upper Senate Park, near the United States Capitol, in Washington DC. Their signs and chants proclaimed, “Don’t Tread on the ADA” and “Our homes, not nursing homes.” After a series of speeches, attendees marched to the Supreme Court.1 They were there to show support for the plaintiffs in a case under review, Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W. The rally protested the on-going segregation of many disabled Americans. It also called for better enforcement of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).2

National Register of Historic Places. NRHP 97000829

The Growth of Institutions

Starting in the nineteenth century, government and private institutions segregated people with disabilities.3 Many schools for deaf, blind, and developmentally disabled students were also founded in the 1800s. Examples include the Agnews Insane Asylum in California, the Institution for Feeble Minded Youth Farm in Nebraska, and the Montana State Training School. Reformers originally envisioned institutions as temporary homes to help people with disabilities. But by the 20th century, many residents were kept in these facilities for life. The number and size of institutions boomed in the decades after World War II. Federal dollars funded large new state schools and hospitals. Abuse and mistreatment ran rampant in these overcrowded facilities. Medical experiments, inadequate food and clothing, and neglect were not uncommon. Institutions also relied on the unpaid work of their residents in order to function.4

George Bush Presidential Library and Museum/NARA

The Integration Mandate

But the expansion of institutions encountered resistance. Beginning in the late 1950s, people with disabilities and their allies rallied against the abuses endured in institutions.5 They knew that, with enough support, disabled people could flourish in their communities. Many state governments argued it saved money to provide centralized care. However, activists showed that in most cases it was less expensive to deliver community-based care. More importantly, most people with disabilities preferred to live outside an institution. They said community living gave them a higher quality of life. Community services can take on many forms depending on the needs of the individual.6 For example:

- Personal care attendants assist with daily tasks like personal hygiene and eating

- Home nurses provide routine medical care

- Job coaches help employees learn and keep a job

These services can empower someone to live alone, with their family or friends, or in a group home with other disabled housemates and a caregiver.

The fight for people’s right to move from a hospital setting to the community is called the deinstitutionalization movement. This movement won a huge victory with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. The law aimed to protect disabled Americans against discrimination. It targeted employment, transportation, public accommodations, and communication. The ADA also endorsed an “integration mandate.” This mandate addressed the historic and on-going segregation of disabled Americans. The ADA required states to offer community-based services in addition to those services in institutions. However, the 1999 Supreme Court case Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W threatened this hard-earned progress.

American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today (ADAPT). 1999

The Court Case

The Olmstead case began when two women in Georgia tried to leave a state-run regional hospital. Lois Curtis (L.C.) and Elaine Wilson (E.W.) had intellectual and psychiatric disabilities.7 The women said they felt trapped at the institution and wanted to leave. Further, doctors said they each would be able to live in the community with support. Yet, Georgia kept them at the state hospital for years. After connecting with the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, Curtis and Wilson filed and won their lawsuit to leave the hospital. The lower courts upheld the integration mandate of the ADA.8 The legal battle did not end there. Thomas Olmstead, Georgia’s Commissioner of Human Services, appealed the decision to the US Supreme Court.9 The Justices agreed to hear the case.

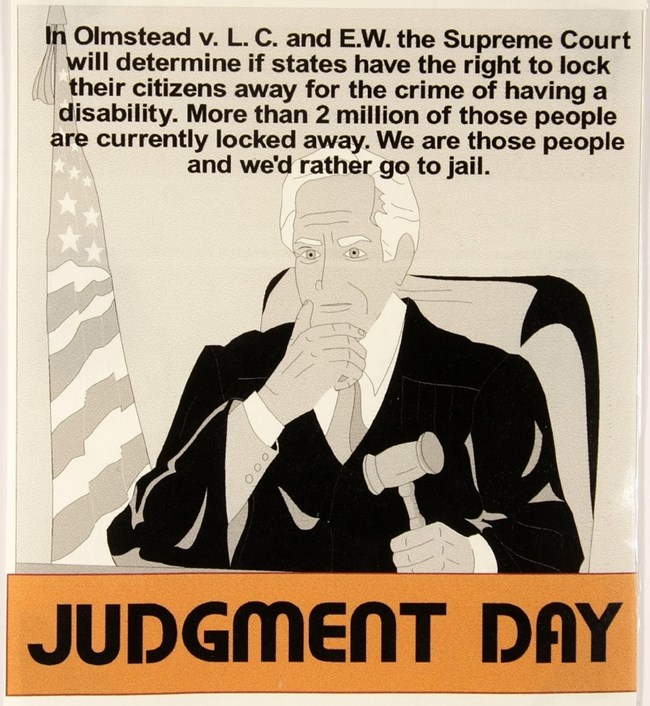

As the first Supreme Court case about the ADA’s integration mandate, the stakes felt high for disabled Americans. At its core was a question of who got to decide where a disabled person lives: the state or the individual? The Supreme Court’s decision became known as Judgment Day as activists waited to see whether the heart of the ADA would remain intact.10

"We’ll do whatever it takes to gain and keep our freedom and our rights,” one former nursing home resident declared in a press release. “No state is going to tell me I have to live in a nursing home. I have as much right as anyone to live in the community.”11

American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today (ADAPT). March 19, 1999.

Activist Mobilization

When the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case in December 1998, the prominent disability organization ADAPT (American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today)12 jumped into action. They pursued the following strategies:

- spread information about the case across their national network,

- pressured their governors and state attorneys general to withdraw support from Georgia,

- wrote postcards to elected officials,

- signed petitions,

- promoted their message to the public, and

- protested at government buildings (for example on January 15, 1999, they demonstrated at a dozen governors’ offices).13

Originally 26 states submitted amicus briefs in support of Georgia’s position. This meant that these other states agreed with Georgia’s legal arguments against Curtis and Wilson’s bid for independent living. However, disability rights activists successfully convinced 19 states to withdraw their support by late spring 1999. According to ADAPT, such a drastic reversal in official support had never been seen before in a Supreme Court case.14

Activists showed the Supreme Court that they would closely follow this case. On April 20,

around one hundred people held a candlelight vigil and press conference with Curtis and Wilson. They spent the night on the sidewalk outside the Supreme Court Building. In the morning, their supporters were first in line to attend the start of the oral arguments.15

During the week of May 10, the Supreme Court discussed Olmstead. Meanwhile, activists from across the US gathered in Washington DC. They kept pressure on officials to support integration. So many disabled activists rode the train from New York City that Amtrak had to remove seats to accommodate sixty wheelchair users. Hundreds of ADAPT activists took over the offices of the National Governors Association and the US Conference of Mayors. Although the police arrested eighty-five people, the activists remained committed. The following day, they surrounded the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Accessible housing was one of the barriers to living independently for people with disabilities. Activists wanted HUD to better enforce the department’s own anti-discrimination regulations. In response to the demonstration, the HUD Deputy Secretary agreed to improve enforcement.16

American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today (ADAPT). May 12, 1999

Don’t Tread on the ADA Rally

To further pressure the Supreme Court and publicize their cause, activists organized a large rally on May 12. Over one hundred organizations and an estimated four thousand participants contributed to the Don’t Tread on the ADA rally.17 It was believed to be the largest disability rights rally to date. Chants and signs declared:

“My control, not state control”

“Integration, not segregation”

“Separate will never be equal”

The event united people from diverse backgrounds. Individuals with physical, developmental, and psychiatric disabilities joined forces to fight the perceived threat to the ADA. According to Tom Olin, a longtime photographer of the disability rights movement, “the objective was to tell the Supreme Court that we were listening to them. We were out there.”18

Several activists spoke and reminded attendees of the rights they had already won. They also talked about the work that remained.19 Among the speakers were key leaders in the creation of the ADA. They included activist Justin Dart, former Attorney General Dick Thornburgh, and Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa.20 Senator Harkin’s speech acknowledged the deeply personal nature of the struggle over independent living and the need to work together to build on past legislative successes:

“I know for many of you here today, this is not a matter of developing policy – it is a literal struggle for your lives, and the lives of your friends and colleagues. I know many of you have lived in institutions yourselves. You know the frustration, you know the indignity, you know the anger that comes from not living free lives in the community. Let me now say this to each one of you: Your struggle for freedom has not been in vain. Your fight to gain the attention of those of us here in Washington is working.”21

After the speeches, demonstrators marched to the Supreme Court Building. At the front of the line was “a mock funeral procession for freedom, including pallbearers and a casket.”22 Marchers chanted their demands for equal rights and sang “We Shall Overcome.” The demonstration ended with a moment of silence for all those who had died in an institution.23

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

Court Decision and Aftermath

On June 22, 1999, the Supreme Court issued its decision: undue institutionalization is discrimination. Grassroots pressure, from lobbying politicians to the DC actions, contributed to this huge victory.24 Activists declared it a win for personal choice and desegregation. The decision remains a cornerstone of disability rights to this day.

Disability activists’ battle against institutionalization did not end with the Olmstead decision.25 Instead, the case gave them another tool to fight with. Activists have pointed out that government programs, like Medicaid, continue to favor institutions over community programs. Especially during economically difficult times, community services are often cut first. Lobbying efforts and direct actions continue, in hopes of securing more funding and services.26 Survivors of institutions have shared about the personal effects of the court case through campaigns like “I am Olmstead."27 As disabled people keep fighting to live where they choose, activist Nadina LaSpina’s words continue to ring true: Olmstead "proves that when we are united, we are powerful and we can make our voices heard."28

This article was written by Ellie Kaplan, MA, National Council for Preservation Education Intern, with the National Park Service Park History Program. 2024.

End Notes

- The Supreme Court Building was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1987.

- Tom Olin & Jim Ward, “A Conversation with Tim Olin & Jim Ward,” interviewed by Peter Blanck, “Section 504 at 50,” 2023, https://section504at50.org/episodes/tom-olin/; Jennifer Burnett, “Power News: Don’t Tread on Our ADA!! Activists Surround Supremes,” Mouth, August 31, 1999.

- Initially there were separate institutions for people with developmental disabilities and for people with psychiatric disabilities.

- For more on the history of institutions see: Steven Noll, “Institutions for People with Disabilities in North American,” in The Oxford Handbook of Disability History, ed. by Michael Rembis, Catherine Kudlick, and Kim E. Nielsen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 307-324.

- An early example of a successful class action lawsuit against an institution was Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Halderman. The plaintiffs argued the Pennsylvania institution, Pennhurst, mistreated its residents who were kept in unlivable conditions. In 1984, the Supreme Court upheld the rights of the residents, including the right to be free from harm and to live in an integrated setting. They ordered that alternative suitable living arrangements be made for all residents and Pennhurst be closed (which it did in 1987). “Halderman v. Pennhurst State School & Hospital,” Disability Justice, https://disabilityjustice.org/halderman-v-pennhurst-state-school-hospital/.

- Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) can be accessed through Medicaid and state programs. For more information see: https://www.cms.gov/training-education/partner-outreach-resources/american-indian-alaska-native/ltss-ta-center/information/ltss-models/home-and-community-based-services. This article includes personal stories of how individuals use different types of community services to live outside institutions: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/olmsteads-role-in-community-integration-for-people-with-disabilities-under-medicaid-15-years-after-the-supreme-courts-olmstead-decision/view/print/

- You can find an interview with Lois Curtis in the Section 504 at 50 series: https://section504at50.org/episodes/lois-curtis/

- “Sue, Louis, and Elaine,” Olmstead Rights, https://www.olmsteadrights.org/iamolmstead/history/; “Olmstead v. LC: History and Current Status,” Olmstead Rights, https://www.olmsteadrights.org/about-olmstead/.

- Georgia argued that it was not considered discrimination for individuals to remain in institutions until community services became available. They argued the wait time was because the state did not have enough funding for community services. Linda Greenhouse, “Pivotal Rulings Ahead for Law On Disabilities,” New York Times, April 19, 1999.

- Jennifer Burnett, “Judgement Day,” Mouth, April 30, 1999.

- ADAPT, “Disabled Activists Say, ‘Integration, Not Segregation,’” US Newswire, news release, May 10, 1999.

- Originally called American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit in 1983, ADAPT grew out of the Atlantis Community, an independent living community, in Denver CO. Their initial focus was getting lifts installed on buses. They became known for their more radical actions, including laying in the streets to block inaccessible buses. After the passage of new transportation protections as part of the ADA in 1990, they changed their name to American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today. Their new central mission was ensuring adequate community services, including attendant programs, to allow disabled people to prosper outside of institutions. Zames Fleischer and Zames, The Disability Rights Movement, 82-85.

- “Activists protest state’s involvement in Supreme Court disability battle,” Associated Press, January 31, 1999; Burnett, “Judgement Day.”

- Burnett, “Power News.”

- LaSpina, “1999 – Washington – Nadina LaSpina”; Burnett, “Power News.”

- ADAPT also lobbied Congressional representatives to pass the Medicaid Community Attendant Services and Support Act (MiCASSA). MiCASSA would require states to provide equal access to services in and out of nursing homes. This act would help people with disabilities live in the community if they wanted. Despite having bipartisan support, Congress never passed the act. Nadina LaSpina, “1999 – Washington – Nadina LaSpina,” ADAPT, https://adapt.org/1999-washington-nadina-laspina/; Burnett, “Power News”; ADAPT, “Disabled Activists Say, ‘Integration, Not Segregation.’”

- Burnett, “Power News.”

- Olin and Ward, “A Conversation with Tim Olin & Jim Ward.”

- T.K. Small, “Thousands Rally in DC: Activists Gather as Supreme Court Examines ADA,” Able Newspaper 5, no 1 (June 1999), https://adaptmuseum.net/gallery/picture.php?/987/category/45; Burnett, “Power News.”

- You can read Thornburgh’s speech here: https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735070925551/viewer#page/1/mode/2up

- Tom Harkin, “‘Don’t Tread on the ADA’ Rally,” May 12, 1999, Folder 207, Speech Files, Thomas R. Harkin Collection, Drake University Archives and Special Collections, Des Moines, IA.

- Burnett, “Power News.”

- Small, “Thousands Rally in DC.”

- Zames Fleischer and Zames, The Disability Rights Movement, 103-105.

- Even with this momentous victory, barriers remained for disabled people to get all the support they needed to live in the community. Disability rights activist Nadina LaSpina critiqued certain aspects of the decision in her 1999 article “Supreme Court Rulings: Victory and Defeat” in DIA Activist, https://www.disabilityculture.org/nadina/Articles/courtrulings.htm.

- Zames Fleischer and Zames, The Disability Rights Movement, 223-224, 250.

- To read more stories from people personally impacted by the Olmstead decision see: https://archive.ada.gov/olmstead/olmstead_about.htm.

- LaSpina, “Supreme Court Rulings.”